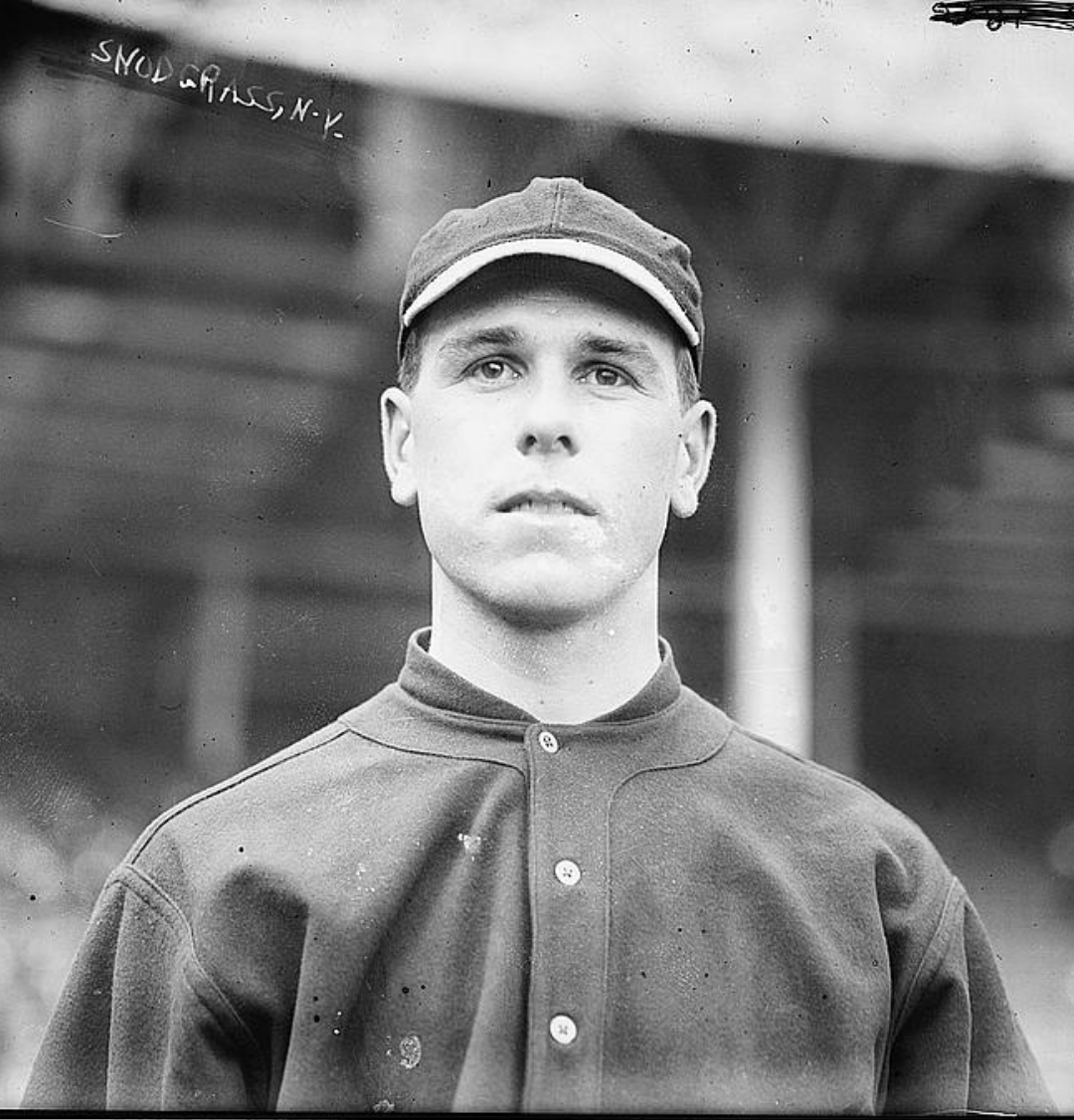

Fred Snodgrass

A regular in the New York Giants outfield from 1910 to 1915, Fred Snodgrass was the “meteor” of the 1910 season, leading the National League in batting average for most of the year before tailing off to finish at .321. The next season Snodgrass batted third in the lineup and ranked second on the club with 51 stolen bases as the Giants set the all-time record with 347. Despite his solid contributions to three pennant-winning clubs, the tenacious center fielder will forever be remembered for his infamous “muff” in the final game of the 1912 World Series. “Hardly a day in my life, hardly an hour, that in some manner or other the dropping of that fly doesn’t come up, even after 30 years,” Snodgrass said in a 1940 interview. “On the street, in my store, at my home . . . it’s all the same. They might choke up before they ask me and they hesitate — but they always ask.” Even death didn’t spare Snodgrass; his 1974 obituary in the New York Times was headlined “Fred Snodgrass, 86, Dead; Ball Player Muffed 1912 Fly.”

A regular in the New York Giants outfield from 1910 to 1915, Fred Snodgrass was the “meteor” of the 1910 season, leading the National League in batting average for most of the year before tailing off to finish at .321. The next season Snodgrass batted third in the lineup and ranked second on the club with 51 stolen bases as the Giants set the all-time record with 347. Despite his solid contributions to three pennant-winning clubs, the tenacious center fielder will forever be remembered for his infamous “muff” in the final game of the 1912 World Series. “Hardly a day in my life, hardly an hour, that in some manner or other the dropping of that fly doesn’t come up, even after 30 years,” Snodgrass said in a 1940 interview. “On the street, in my store, at my home . . . it’s all the same. They might choke up before they ask me and they hesitate — but they always ask.” Even death didn’t spare Snodgrass; his 1974 obituary in the New York Times was headlined “Fred Snodgrass, 86, Dead; Ball Player Muffed 1912 Fly.”

Frederick Carlisle Snodgrass was born in Ventura, California, on October 19, 1887, the youngest of three children of Andrew and Addie Snodgrass. A Kentucky native who worked as a sheriff and later as a private patrolman, Andrew moved to the West Coast and married Addie, a California native, in 1874. One of Fred’s brothers was retarded and spent many years in the California Home for Feeble Minded Children, dying in 1912 at age 33. Fred attended St. Vincent’s College, a Catholic school in Los Angeles that later merged with Loyola Marymount University. Catching for the St. Vincent’s baseball team, his hustle caught the eye of John McGraw while the Giants were training in Los Angeles during the spring of 1907. Fred also caught McGraw’s ear by arguing with him throughout one game in which McGraw acted as umpire. In Los Angeles the following winter for the horseracing season, McGraw inquired after Snodgrass and offered him a contract. Fred joined the Giants after the school year ended in June 1908, making his debut as a catcher but collecting only four at-bats the entire season.

In 1909 it became apparent that Chief Meyers was going to succeed Roger Bresnahan as the Giants catcher, so McGraw tried the speedy Snodgrass all over the diamond, finally settling on the outfield. Still an apprentice, “Snow” logged only 70 at-bats that season but hit .300, stole 10 bases, and demonstrated a willingness to unleash his quick temper on opposing teams rather than his manager. In 1910 Snodgrass played most of the time in center field and quickly established himself as a coming star. His average peaked at .377, and as September began he led the NL at .362 and was in contention for a Chalmers automobile to be presented to the major leaguer with the highest batting average. In over his head while trying to keep pace with Ty Cobb and Nap Lajoie, Snodgrass stopped hitting and faded to .321, still good enough to rank fourth in the NL behind Sherry Magee, Vin Campbell, and Artie Hofman.

Snodgrass remained McGraw’s center fielder for half a dozen years, joining the lineup at the same time as Meyers, Fred Merkle, and Josh Devore. Winners of three straight pennants from 1911-13, the team was built around speed; in 1910 Snodgrass stole 33 bases and was fourth on the team, behind Red Murray, Devore, and Larry Doyle. In 1911 Snodgrass was second with 51 steals, his career high. That was his best full season, as he also finished third on the team with 83 runs scored and 77 driven in. He made solid contributions to the next two pennant-winners, scoring 91 runs in 1912 and hitting .291 in 1913.

Unfortunately, Snodgrass ran into major problems in the World Series, beginning in 1911. In Game Three, he led off the bottom of the 10th inning in a 1-1 game with his favorite maneuver, intentionally getting hit by a pitch. The umpire didn’t buy it, but he did draw a walk, and after a sacrifice bunt he tried to advance on a short passed ball. The throw to Frank Baker at third base beat Snodgrass easily, so he leaped at Baker, hitting him spikes first as the tag was applied. He had done the same thing earlier in the Series, but this time he inflicted a wound that took several minutes to treat. Baker had the last laugh when he homered in the 11th inning to win the game, but all of Philadelphia was scandalized by what they saw as a deliberate attempt by Snodgrass to injure Baker. The next day, after Game Four was rained out in Philadelphia, Snodgrass felt the fans’ wrath. “Snodgrass Hooted Out of Philadelphia,” read the front-page headline in the New York Times. As the rains and abuse continued, McGraw sent Snodgrass back to New York amid rumors that he had been shot. When play resumed after a week of postponements, Snodgrass went hitless in the final three games, batting only .105 for the Series as the Athletics won in six games.

It only got worse for Snodgrass in the 1912 World Series, when he made one misplay that became his legacy. With the Giants leading 2-1 in the bottom of the 10th of the deciding game, Fred dropped an easy fly ball by leadoff batter Clyde Engle for a two-base error. The ball was hit more toward right fielder Red Murray, but on the Giants the center fielder was supposed to call for everything he could reach. Snodgrass made the call, Murray stepped aside, and, as Snodgrass explained in later years, “because of over-eagerness, or over-confidence, or carelessness, I dropped it.” He was forever blamed for the winning rally that ensued, but two other events also contributed to the downfall of the Giants. The next batter, Harry Hooper, drilled a long shot that Snodgrass speared for a spectacular catch. In a just world, he would’ve caught the first ball and the second would’ve gone for a double, yielding the same outcome. The key to the inning was a high foul pop by Tris Speaker on which Christy Mathewson made the mistake of calling for Chief Meyers to make the catch. Meyers couldn’t reach the ball, while Merkle, who could have caught it easily, stood still as directed by Mathewson. Given a reprieve, Speaker singled to score the tying run and set up the Series-winner.

Snodgrass stayed with the Giants until a mid-1915 trade to Boston, where he had been involved in a rhubarb the previous season. During a Labor Day showdown for first place, Braves pitcher Lefty Tyler knocked Snodgrass down four pitches in a row, then mocked his muffed catch. Snodgrass mouthed off, and when the fans kept on him he thumbed his nose at everyone, bringing Boston mayor James M. Curley onto the field to demand an ejection. McGraw stood by Snodgrass that day, but a prolonged batting slump landed him in Braves Field in 1915. Fred’s contract expired after the 1916 season. Rather than sign for much less, he went home to California, spent 1917 in the Pacific Coast League, and retired to go into the appliance business.

If Snodgrass was hounded through the years by reminders of his biggest failure, it didn’t prevent him from thriving in life. A successful businessman and banker in Oxnard, he was elected to the City Council in 1930 and served three terms before being appointed mayor early in 1937. He held the office for 11 months before resigning to move to Ventura, where he bought a ranch, grew lemons and walnuts, and continued to prosper with his wife, Josephine, and their daughter, Eleanor. In 1963 Larry Ritter visited Snodgrass and their time together resulted in the longest chapter in The Glory of Their Times. Snodgrass explained how he wore a baggy uniform to get hit by pitches, compared his “muff” to Merkle’s Boner, revived the legends of Bugs Raymond and Victory Faust, and told Ritter what it felt like to be one of McGraw’s Giants. Fred Snodgrass died in 1974 at age 86.

A slightly different version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., “Deadball Stars of the National League” (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

Sources

For this biography, the author used contemporary newspapers and material from the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

Frederick Charles Snodgrass

Born

October 19, 1887 at Ventura, CA (USA)

Died

April 5, 1974 at Ventura, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.