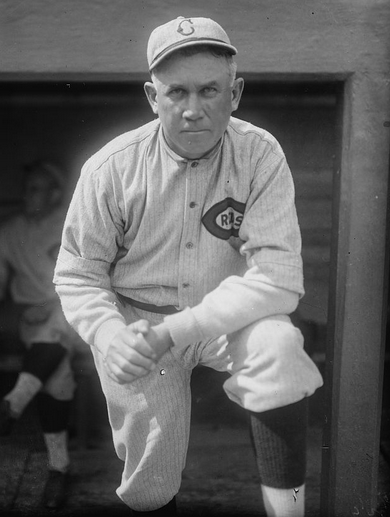

Pat Moran

Back in an era when a manager’s responsibilities often included both the duties of a modern skipper plus those of today’s general manager, Pat Moran excelled at each role. In a span of six years Moran took over two mediocre franchises with little history of winning, rebuilt and reassembled their players, and managed each to a pennant. Unfortunately, his place in the pantheon of great managers never solidified due to his unexpected and premature death at age 48.

Back in an era when a manager’s responsibilities often included both the duties of a modern skipper plus those of today’s general manager, Pat Moran excelled at each role. In a span of six years Moran took over two mediocre franchises with little history of winning, rebuilt and reassembled their players, and managed each to a pennant. Unfortunately, his place in the pantheon of great managers never solidified due to his unexpected and premature death at age 48.

Patrick Joseph Moran was born on February 7, 1876, in Fitchburg, Massachusetts. He began playing baseball at a young age and took to the catcher’s position almost immediately. While still quite young, Moran began working for the American Woolen Company in one of the local textile mills for $3 per week. When not working Moran played on local baseball teams with teammates several years older. Moran later joined a well-organized and successful amateur team, Fitchburg A.C., where he first received more than local attention. Owing to his stellar play behind the plate, Moran was soon recruited to play for a semi-professional club in Orange, Massachusetts.

Moran’s strong play next attracted the attention of Organized Baseball, and he moved to the Lyons club in the New York State League for the 1897 season. He spent two years at Lyons before they sold him to Montreal of the Eastern League, where he spent two additional seasons before joining the National League’s Boston Beaneaters in 1901. Despite never exceeding a batting average of .288 in his four minor-league seasons and attaining just average fielding percentages (although he was known for having a strong arm), during his final campaign some touted him as the top catcher in the Eastern League. To acquire Moran, Boston paid $1,000 and further agreed that if Boston decided to “loan” pitcher Togie Pittinger to a minor-league team, Montreal would receive first crack at him.

The Beaneaters team Moran joined in 1901 was led by future Hall of Fame manager Frank Selee, a man Moran later credited for his own managerial success. The Beaneaters had been one of baseball’s most successful franchises during the 1890s, winning five pennants, and still had some excellent pitchers for Moran to work with, including future Hall of Famers Vic Willis and Kid Nichols. Moran spent five years in Boston, playing more or less regularly after his rookie season. He had his best year in 1903, batting a career high .262 with seven home runs. Additionally, he set the major-league single-season record for assists by a catcher with 214, a mark that still stands.

Prior to the start of the 1906 season, the Chicago Cubs purchased Moran to back up Johnny Kling, then the league’s top backstop. The timing of the move proved fortunate for Moran, as he became a valuable reserve on the great Chicago teams of 1906-1908. In those years few catchers caught more than 100 games a year, so even as a backup he typically manned the position for more than 50 games a season. It was while in Chicago that Moran met his future wife, a marriage that led to two children.

In 1910 Moran moved on to Philadelphia to help spell catcher and player-manager Red Dooin, who was suffering from a broken ankle. Horace Fogel, president of the Philadelphia Phillies until ousted from the National League after the 1912 season for publicly and aggressively accusing the league and umpires of conspiring to throw the race to the New York Giants, later recounted the circumstances surrounding Moran’s coming to the Phillies.

In July the Cubs had waived Moran with the intention of sending him down to Louisville in the American Association. Much to the consternation of Cub president Charles Murphy, Fogel claimed Moran, and after some haggling the Phils secured Moran for $2,500. As his playing time dwindled over the next couple of years, the Phillies organization recognized Moran’s intelligence and ability with pitchers, and his duties evolved into those of a pitching coach, a role in which he excelled. Dooin eventually became jealous of Moran’s expertise and reputation. He looked to move Moran off the club, but Fogel recognized Moran’s talent and vetoed any action.

Fogel also gave Moran the credit for developing pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander, one of the greatest hurlers of all time. Fogel described how Alexander had a “peculiar and non-effective delivery” when he first showed up in spring training in 1911 after being drafted for $750. Moran recognized Alexander’s ability and, together with Earl Moore, converted Alexander to his famous sidearm motion. Phillies historian David M. Jordan corroborates Moran’s early recognition of Alexander’s ability. He writes that Dooin wanted to send Alexander back to the minors after a poor spring, but Moran convinced Dooin to give him one final spring start; Alexander pitched well and made the club.

The next year another future Hall of Fame pitcher joined the Phillies. Eppa Rixey jumped to the major leagues straight from the University of Virginia campus at the close of the school year in June. Moran worked diligently with the new collegian, and Rixey credited him with much of his success. “It was Pat who made a pitcher out of me and I was fortunate to play under him in both Philadelphia and Cincinnati,” Rixey recalled. “Few men that I’ve ever known in baseball knew the fine arts of pitching as did Moran.”

During Moran’s active stint with the Phillies as a player, the club usually finished in the middle of the pack. In 1913, however, with two of the league’s best players, pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander and outfielder Gavvy Cravath, the club jumped to second with 88 wins. That winter, though, the Phillies suffered more than most clubs from defections to the rival Federal League, losing their keystone combination and a couple of starting pitchers. The next season the Phillies slumped all the way to sixth, and owner William Baker jettisoned longtime manager Dooin. The players strongly backed the elevation of Moran and Baker agreed, naming him manager in October 1914.

Since Moran received only a one-year contract, for $4,500, some doubt existed as to how he would do with a mostly veteran team filled with players on long-term contracts. A Philadelphia writer noted that the veteran Phillies were “not keen for keeping the rules of training and that they were mighty hard to handle.” Moran, known as a hard worker, proved up to the task of instilling discipline into the club.

Moran also set about making a number of personnel moves that would transform the sixth-place Phillies of 1914 into a pennant winner in 1915. Although the deals were not particularly celebrated at the time, a year later they were deemed “so successful they could be counted as ‘once in a lifetime’ affairs.” Two weeks after Moran’s hiring, the Phillies purchased the contract of future Hall of Famer Dave Bancroft from Portland of the Pacific Coast League. Moran immediately installed Bancroft at shortstop, where the rookie would prove highly proficient.

Removing Dooin as manager raised the question of what to do with him as he was still regarded as a valuable backup catcher. Moran first worked out a trade with Brooklyn manager Wilbert Robinson for George Cutshaw to fill the need at second base. Dooin did not want to report to Brooklyn and threatened to jump to the Federal League unless given a salary of $8,000 per year. Not surprisingly Brooklyn owner Charles Ebbets refused to pay this for a backup catcher. Although much of this salary demand was merely posturing — Dooin would have accepted less — the transaction never came together.

Moran finally resolved the potential dilemma of having a fired ex-manager on the team by trading Dooin to the Cincinnati Reds for starting third baseman Bert Niehoff, and then astutely shifting Niehoff to second base. Another forced trade involved slugging outfielder Sherry Magee, who had also threatened to jump to the Federal League. Described during the disappointing 1914 season as the “quarrelsome captain of the shot-to-pieces Quakers,” Magee had hoped to be named manager after Dooin’s ouster. Moran shipped Magee to the Boston Braves for Oscar Dugey, a reserve infielder, and George “Possum” Whitted, a 25-year-old outfielder.

In his final major off-season trade, Moran sent 33-year-old third baseman Hans Lobert to the New York Giants for a mid-level starter, Al Demaree; a 22-year-old third baseman, Milt Stock, who would be a valuable starter by the end of the year; backup catcher Jack Adams, and cash. Thus, by the start of the 1915 season Moran and the Phillies had replaced their Federal League losses at second base and shortstop, while adding new starters at third base and in the outfield.

Regaining the league lead on July 14, Philadelphia never looked back, winning the pennant by seven games over the defending champion Boston Braves. After winning the first World Series game, 3-1, the Phillies dropped four consecutive one-run games to the American League champion Boston Red Sox, three by the score of 2-1.

In the deciding Game Five, the Phillies loaded the bases in the first inning with no one out and slugger Cravath coming to the plate. Moran noticed Boston third baseman Larry Gardner playing deep and ordered Cravath to bunt. Cravath’s bunt, unfortunately, rolled to pitcher George Foster, who started a home-to-first double play. The next batter, Fred Luderus, doubled home two runs to salvage something from the inning, but a potential breakout first inning had been squelched. Moran later defended his decision, arguing he was trying to pull the unexpected and cross up the Red Sox.

As a harbinger of things to come, Baker took his time about resigning Moran, who had finished his one-year contract. After some fairly arduous negotiations, Moran signed a three-year deal for a total of $25,000. Over the next couple of years, Baker continued to exhibit his parsimonious ways. The Phillies essentially stood pat with their roster, making few moves to improve. The club finished 91-62 in 1916, a one-game improvement over 1915, but slowed by a late-season injury to Bancroft they finished second, two and a half games behind the Brooklyn Dodgers. Another second-place finish followed in 1917, although at 87-65 they lagged 10 games behind the Giants.

Following the 1917 season, Baker sold the National League’s best pitcher, Alexander, and one of its best catchers, Bill Killefer, to the Chicago Cubs for $55,000 and a couple of second-rate players. The departure of other players soon followed, and the Phillies fell to sixth in the war-muddled 1918 season. With his three-year contract now expired and Baker actively pursuing player sales to make money, Moran must not have been too disappointed when Baker released him after the season. John McGraw, the Giants manager and a long-time friend, snapped Moran up as his pitching coach at a salary of $5,000, one of the era’s highest for a coach.

Shortly thereafter Cincinnati Reds owner Garry Herrmann hired Moran away from the Giants to manage his club in 1919. Christy Mathewson, the 1918 skipper, had been sent to Europe with the Allied Expeditionary Force, and Herrmann was unsure of Matty’s status for the coming season. The Reds had finished slightly above .500 in each of the previous two years, but with the exception of center fielder Edd Roush and third baseman Heinie Groh, they were a mediocre team. The shortened 1918 season, with the attendant loss of many players to the armed services or essential industries, jumbled the campaign and the prospects for 1919.

As he had several years previously with the Phillies, Moran took advantage of the turmoil and set about recasting his new club for a pennant run. The Reds traded shortstop Larry Kopf and outfielder Tom Griffith for Jake Daubert, one of the era’s top first basemen. When Kopf failed to report to Brooklyn, Moran swapped his own holdout second baseman, Lee Magee, to get his shortstop back and filled the void at second base by bringing up Morris Rath from the minor leagues.

Moran also rebuilt a pitching staff that had been mediocre prior to his arrival. In the three years leading up to 1919, the club had not recorded an ERA better than the league average and twice finished as low as seventh. In Moran’s five years managing the Reds, the team never finished with an ERA greater than the league average and only once ranked lower than second. The Reds claimed Slim Sallee from the Giants on waivers, and in 1919 Sallee would finish second in the league with 21 wins. Moran snatched up Ray Fisher, waived by the Yankees in March. He also installed pitcher Dutch Ruether, claimed off waivers from the Cubs in 1917 but used sparingly since, into the starting rotation; Ruether would lead the league in winning percentage in 1919. Holdovers Hod Eller and Jimmy Ring rounded out the starting rotation.

The Reds won the 1919 pennant with a winning percentage of .686, the highest since the 1912 Boston Red Sox. They then defeated the Chicago White Sox in the World Series five games to three for the Reds first World Championship. Of course this was the infamous “Black Sox” series in which a number of the Sox conspired with gamblers to give less than their best effort. During the Series rumors flourished that gamblers had influenced the White Sox; prior to the eighth game Roush heard that gamblers might have manipulated some Reds players as well. Roush went to Moran with his fears, and Moran confronted that day’s starter, Hod Eller. Roush remembers the exchange as Moran called Eller over:

“Hod, I’ve been hearing rumors about sellouts. Not about you, not about anybody in particular, just rumors. I want to ask you a straight question and I want a straight answer.”

“Shoot,” replied Hod.

“Has anybody offered you anything to throw this game?”

“Yep,” Hod said, and Roush recalled you “could have heard a pin drop.”

Eller continued, “After breakfast this morning a guy got on the elevator with me, and got off at the same floor I did. He showed me five thousand-dollar bills, and said they were mine if I’d lose the game today.”

“What did you say?”

“I said if he didn’t get damn far away from me real quick he wouldn’t know what hit him. And the same went if I ever saw him again.”

Moran decided to let Eller pitch, but told him “one wrong move and you’re out of the game.” As it happened Eller started and won the decisive Game Eight after getting staked to a four-run lead in the first inning.

In 1920 the Reds returned with an almost identical club; only right fielder Pat Duncan, now back from military service, represented a change in the regular lineup. In addition, Moran inserted Cuban hurler Dolf Luque into the starting rotation. Under Moran’s tutelage, Luque, already 29 years old, became one of the top pitchers of the early 1920s. The Reds battled the Giants and Dodgers throughout the season and regained first place as late as Labor Day. But a broken thumb to shortstop Larry Kopf in late August shelved him for the season and may have contributed to a horrible September as the Reds limped home third.

Coming off of the 82-71 finish in 1920, owner Herrmann and Moran decided to revamp the pitching staff, which had fallen to fourth. While Moran had coaxed excellent seasons out of his staff in 1919, with the exception of Luque the pitchers were little more than journeymen by 1921. Moran presciently recognized the limitations of his pitchers and brought in a couple of solid additions. He swapped Ruether to Brooklyn for Rube Marquard, who had drawn the ire of Brooklyn owner Charles Ebbets after his arrest and conviction for ticket scalping in Cleveland during the 1920 World Series. In one of his best trades, Moran reacquired his old hand Eppa Rixey from the Phillies for Jimmy Ring and outfielder Greasy Neale.

Unfortunately, the Reds were so devoid of outfield talent after the trade of Neale that Moran was left to the expedient of converting relief pitcher/reserve outfielder, Rube Bressler, into a regular for 1921. Moran did bring in several young position players from the minors but none were outfielders. He purchased Sammy Bohne and Lew Fonseca, both destined to play semi-regularly at second base for the Reds over the next few years. More importantly, Cincinnati acquired catcher Bubbles Hargrave from St. Paul in the American Association for $10,000. Hargrave would become one of the league’s best catchers over the 1920s.

The 1921 season would get off to a rocky start and not improve. The club witnessed the discontent of several players, which significantly disrupted the year. For the 1921 season pitcher Ray Fisher had signed a contract for $4,500, a $1,000 pay cut after finishing only 10-11 the previous year but with a 2.73 ERA in 201 innings. Not surprisingly, he was extremely unhappy with the pay cut and signed the contract only after objecting strongly. Just prior to the start of the season he visited the University of Michigan campus in Ann Arbor to interview for the head baseball coaching position. Michigan offered Fisher the job at a salary of $5,000, and with the offer in hand he went back to Moran and Herrmann and asked for his release. The two refused, but offered a raise. Fisher countered with a request for a two-year contract, which Cincinnati refused.

Fisher thereupon left to coach Michigan under the assumption that he would be placed on the voluntarily retired list as allegedly promised by Herrmann. Herrmann stunned Fisher when he instead placed Fisher on the ineligible list (i.e., the list of banned players) for jumping his contract. Near the end of the college season, Fisher began lobbying to get back into major-league baseball, either with the Reds or another team. Unsure of his precise status, Fisher began negotiating with a Pennsylvania team in an outlaw league (i.e., a league that allowed blacklisted players) as a fallback.

While in Chicago near the end of the college baseball season, Fisher called on Commissioner Landis to clarify his status. As part of the conversation, Fisher claimed he had been given permission by Moran to visit Ann Arbor in the spring to interview for the job. In his subsequent investigation Landis contacted Moran who maintained that he “positively refused to grant” such permission. At the conclusion of his investigation Landis permanently expelled Fisher from Organized Baseball, generally regarded as one of his more egregious decisions. Landis evidently believed Moran over Fisher, and Landis biographer David Pietrusza believes that Fisher’s apparent lie was one of the main reasons Landis banned him.

The Reds also found themselves with a couple of holdouts, Heinie Groh and Edd Roush, the team’s two best players. Roush held out nearly every year and would soon report, but the Groh matter caused acute problems, as he had grown bitter and disillusioned and wanted out of Cincinnati. In the late spring after the New York Giants reportedly offered $100,000 and three players for him, Groh was willing to sign for $10,000 with the Giants, rather than the $12,000 he was demanding from Reds owner August Herrmann. The Reds were more than happy to sign and sell Groh at this price.

Landis voided the sale and ruled Groh must finish out the season for Cincinnati. Although historically players had sometimes forced trades through holdouts, Groh’s case caused an uproar from other clubs, and Landis ruled that it would be detrimental to the sport if “by the hold-out process a situation may be created disqualifying a player from giving his best service to a public that for years has generously supported that player.” This is a curious ruling from a Commissioner who liked to think he sided with the underdog players. Most likely given the atmosphere of the time, less than a year after the Black Sox Scandal became public, Landis somehow got Groh’s holdout confounded with all the gambling gossip and general concerns about players not giving their best.

Without Fisher, Moran worked his big three starters of Luque, Rixey, and Marquard to 107 starts among them; no one else had more than 11. The three delivered for Moran, and the staff turned in the league’s second-best ERA. During the season the Reds further bolstered the staff by signing Pete Donohue from Texas Christian University for a $5,500 bonus. Moran astutely recognized his talent and inserted him into the rotation for the second half of the year. The offense, however, could offer only three quality batters: Roush; Groh, now past his prime and, in any case, a holdout for much of the season; and Daubert, now 37 and suffering through one of his worst seasons. The team scored only one more run than the hapless Phillies and well over 200 fewer than the league-leading Giants. The pitching staff could not overcome the offensive woes, and the team fell all the way to sixth.

In December McGraw again came after Heinie Groh now that his trade ban had expired. Again offering a huge amount of money, somewhere around $100,000, along with outfielder George Burns and journeyman catcher Mike González, McGraw finally got his man. For many years baseball’s top third baseman, Groh was now 32. One could hardly fault Herrmann for accepting the money and a solid starting outfielder to help his undermanned outfield.

Moran now recognized the deficiencies in his offense and put together several transactions to improve it. He traded hurler Hod Eller, who had torn ligaments in his arm after his stellar 1919 campaign, to Oakland in the Pacific Coast League for third baseman Babe Pinelli. To further bolster the outfield, Moran acquired minor-league veteran George Harper from Oklahoma City. To succeed the light-hitting Kopf at shortstop Moran sent $25,000 of the loot from the Groh sale and two players to San Francisco (PCL) for Ike Caveney. Already 27 years old, Caveney actually offered little improvement over Kopf. Inserting the hard-hitting Hargrave into the starting lineup provided additional punch to the offense.

The Reds also made one further move to improve the pitching staff by acquiring Jack Scott from the Braves for Larry Kopf and Rube Marquard. Scott had been an excellent pitcher for the Braves but unfortunately experienced shoulder problems in the spring with the Reds. The Reds hoped to have the Commissioner’s office annul the trade, but lacked solid evidence that the Braves knew of Scott’s arm condition at the time of the swap. Thus, in April the Reds simply released him. To finish Scott’s story, he then retired to his tobacco farm in North Carolina. By late summer, however, his arm began feeling better and he contacted New York Giants manager John McGraw for a tryout. McGraw took a flier and signed Scott who went on to several excellent seasons as a valuable swingman for the Giants.

The Reds suffered a further setback at the start of the 1922 season with yet another prolonged holdout by Edd Roush. This time it turned into an extended standoff, and Roush did not report until July.

Nonetheless, Moran had performed his magic once again. He had overhauled his overachieving World Series pitching staff, and his starting eight included only two players, Daubert and Roush, from his 1919 champions. Despite the Scott fiasco and the Roush holdout, the Reds jumped to second, finishing behind only the Giants. The pitching staff again recorded the second-best ERA in the league, and the offense improved to the middle of the pack.

Moran generally liked the makeup of his club and returned essentially the same collection of players for 1923. Once again the Reds became embroiled in controversy when they purchased and signed pitcher Rube Benton from St. Paul. A longtime veteran of the New York Giants, in 1921 Benton had been informally blacklisted by the two leagues for having guilty knowledge of the Black Sox fix. He had not, though, been officially banned, and in 1922 Benton played within Organized Baseball for St. Paul. Herrmann took a chance and acquired Benton, at which point the league ruled him ineligible. Commissioner Landis, however, shocked league president John Heydler and the owners by ruling Benton was indeed eligible. After some hand-wringing by the Heydler and National League, Landis’ decision stood and Benton joined the Reds.

With his solid second-place club of 1922 now augmented with the addition of Benton, the 1923 Reds were in the heat of the pennant race for much of the summer. In early August Cincinnati stood only three games behind the first place Giants when they hosted New York for a five game series. Unfortunately, the Giants captured all five to drop the Reds eight games back and virtually eliminate Cincinnati’s chance at the flag.

More gambling hullabaloo erupted around the club on August 18, when Collyer’s Eye, a sports gambling sheet, alleged that Bohne and Duncan had been approached by an agent of New York gamblers and offered $15,000 to throw games during the Giant series. The two players vehemently denied the charge. Landis and Heydler dismissed the accusations as malicious gossip from a scandal sheet. In fact Landis urged the two to sue for libel, which they did. In the event, the case did not come to trial until 1928, at which time the article was found libelous, and the two players settled for $50 each plus court costs.

The Reds rebounded slightly after the series loss to the Giants; in the end the Reds finished second, four and one-half games behind the Giants. During the off-season Cincinnati again looked to make a couple strategic moves to reinforce their already strong club. For $35,000 the Reds purchased star hurler Carl Mays, who had fallen out of favor with the Yankees.

Moran had always been a heavy drinker, and over the winter of 1923-24 his drinking worsened, and he began skipping some meals as well. By the time he arrived in Orlando for spring training he was already quite ill. His condition quickly deteriorated, and on March 7 at the age of 48 he passed away, the cause of death given as Bright’s disease, a kidney ailment.

Although Pat Moran never became a star and played in more than 100 games only twice, he nevertheless proved a valuable player on several teams. More significantly, he excelled at all aspects of the manager’s job, from assembling the players, to coaching the pitchers, to orchestrating a game, to the handling of men. After inheriting two of the National League’s also-ran clubs he finished first twice, including one World Series championship, and second four times in only nine years of managing. For this brief period, Moran managed at as high a level as any manager ever. Sadly, a premature death robbed him of the extensive career he could have enjoyed.

In contrast to some other managers of the era, Pat Moran showed that a skipper could win while treating his players fairly and honestly. Moran once summarized his thoughts on the subject, “As leader, it is my business to give orders, and these are always carried out. Not by the ‘mailed fist’ method, as I do not believe in that style, but as one friend to another. The players carry them out because they have confidence in me.”

An earlier version of this biography appeared in SABR’s “Deadball Stars of the National League” (Brassey’s, Inc., 2004), edited by Tom Simon.

Sources

A number of sources were consulted as part of researching this biography. Moran’s Hall of Fame Library clipping file offered a significant number of articles. On Moran’s tenure as manager of the Phillies see Paths to Glory, How Great Baseball Teams Got That Way by Mark L. Armour and Daniel R. Levitt and Occasional Glory, The History of the Philadelphia Phillies by David M. Jordan. For his stretch on the Reds, the best source is The Cincinnati Reds by Lee Allen.

For first-person reminiscences, the unsurpassed The Glory of Their Times by Lawrence Ritter has interviews with several players who played for Moran including Edd Roush and Heinie Groh. A long interview with Edd Roush also appears in Baseball Between the Wars: Memories of the Game by the Men Who Played It by Eugene Murdock.

For the matters involving Commissioner Landis, Judge and Jury: The Life and Times of Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis by David Pietrusza is excellent. The individual scandals are also well covered in Baseball: The Golden Age by Dr. Harold and Dorothy Seymour and The Fix Is In: A History of Gambling and Game Fixing Scandals by Daniel E. Ginsburg. Obviously there are numerous books of varying quality on the fixed 1919 World Series. One important recent contribution is Rothstein: The Life, Times and Murder of the Criminal Genius Who Fixed the 1919 World Series, by David Pietrusza.

Now that they are digitized and available, The Sporting News and the New York Times make exceptional sources that can be explored relatively easily. The Times is superb for digging out contemporary information for particular events. The Sporting News is useful for this as well, although it is at least as valuable as a source of player career summaries through their quite comprehensive obituaries, even for non-star players.

Finally, two standard baseball reference books, Total Baseball and The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball are essential. The 2004 edition of The Baseball Encyclopedia by Pete Palmer and Gary Gillette is necessary and suitable in the absence of Total Baseball.

Full Name

Patrick Joseph Moran

Born

February 7, 1876 at Fitchburg, MA (USA)

Died

March 7, 1924 at Orlando, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.