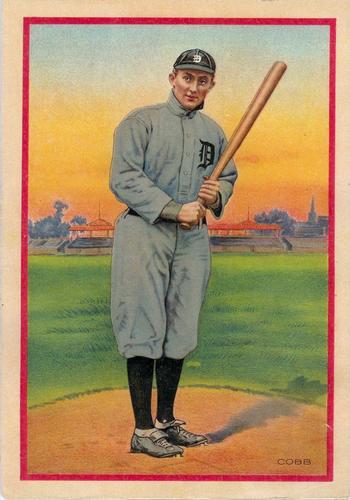

Ty Cobb

Perhaps the most competitive and complex personality ever to appear in a big league uniform, Ty Cobb was the dominant player in the American League during the Deadball Era, and arguably the greatest player in the history of the game. During his 24-year big league career, Cobb captured a record 11 (or 12) batting titles, batted over .400 three times and won the 1909 Triple Crown. Upon his retirement he held career records for games played (3,034), at bats (11,440), runs (2,245), hits (4,189), total bases (5,854), stolen bases (897), and batting average (.366).

Perhaps the most competitive and complex personality ever to appear in a big league uniform, Ty Cobb was the dominant player in the American League during the Deadball Era, and arguably the greatest player in the history of the game. During his 24-year big league career, Cobb captured a record 11 (or 12) batting titles, batted over .400 three times and won the 1909 Triple Crown. Upon his retirement he held career records for games played (3,034), at bats (11,440), runs (2,245), hits (4,189), total bases (5,854), stolen bases (897), and batting average (.366).

Adopting an aggressive, take-no-prisoners style of play which mirrored his fiery temperament and abrasive personality, Cobb dominated the game in the batter’s box and on the base paths. At the plate, the 6’1″, 175-pound left-handed swinger often gripped the bat with his hands several inches apart, but usually brought them back together during his swing. A powerful hitter, Cobb led the league in slugging percentage eight times, and paced the circuit in doubles three times and triples four times. Yet he was also a scientific hitter who liked to beat out bunts and infield grounders for base hits. After 1920, Cobb became a passionate defender of the Deadball Era-style of play, derisively mocking the “swing crazy” batters of the modern game who had neglected the inside strategies mastered by the Georgia Peach.

Tyrus Raymond Cobb was born December 18, 1886 in The Narrows, Georgia, the oldest of three children of William Herschel Cobb, a school teacher, and his 15-year-old wife Amanda Chitwood Cobb, who came from a prominent Georgia family. Young Ty developed a passion for baseball — as did his younger brother Paul, who later spent nine years in the minor leagues — and by the time Ty was 14 he was playing on the Royston, Georgia town team. Cobb soon became a standout on the team and began to focus his energies on baseball, a development that did not please his father.

W.H. Cobb was an educated man, and wanted his son to be a professional. But, while highly intelligent, young Ty didn’t enjoy his studies, and efforts by his father to interest him in law or medicine were unsuccessful. However, Cobb loved, respected, and even idolized his father. W.H. Cobb was by far the most influential person in Ty’s life. As Cobb related much later, “My father was the greatest man I ever knew. He was a scholar, state senator, editor, and philosopher. I worshiped him. He was the only man who ever made me do his bidding.”

In 1904 Cobb, encouraged by a Royston teammate who had had a failed professional tryout, contacted teams in the newly formed South Atlantic (Sally) League. He received a response from the Augusta (Georgia) Tourists, inviting Cobb to spring training provided the boy pay his own expenses, and offering him a contract for $50 per month, contingent on Cobb making the team. For young Tyrus, this was a dream come true, a chance to play professional baseball. His father tried to talk him out of the decision, but finally relented, telling his son, “You’ve chosen. So be it, son. Go get it out of your system, and let us hear from you.”

Cobb was released just two games into his stay with Augusta, but immediately received an offer from a semipro team in Anniston, Alabama. Cobb called his father, who advised him “Go for it. And I want to tell you one other thing — don’t come home a failure.” These words were to have a great impact in shaping the life and baseball career of Ty Cobb. Cobb played well with Anniston, and by August he received a telegram from Augusta asking him to rejoin the team.

The year 1905 was to be a fateful one for Cobb. He reported to Augusta for spring training, and got the chance to play in two exhibition games against the Detroit Tigers. The Tigers trained in Augusta in return for an option to purchase one player from the Augusta team at a later date. Cobb made an impression on the Tigers with his talent and his aggressive, even reckless, style of play.

Augusta got off to a poor start, and Cobb’s play was uninspiring. In July, however, veteran George Leidy replaced Andy Roth as manager, and took Cobb under his wing. He told young Ty that he was wasting his talent, and schooled him in the finer points of the game. Cobb became the league’s best hitter, and Detroit and other teams began to take notice. The tutelage of Leidy was the turning point in Cobb’s career.

Unfortunately, August 1905 brought a tragedy that became a major turning point in Ty Cobb’s life. On the evening of August 8, W.H. Cobb had left home announcing to his wife that he was going to their farm and would not be back that night. As it turned out, the elder Cobb suspected his wife of infidelity, and he returned to the house with a pistol later that night. Shortly after midnight he climbed up on the porch roof and approached the bedroom window. Exactly what happened next is unknown, but Amanda Cobb put two bullets into her husband, killing him. She claimed to have mistaken her husband for a burglar, but the physical evidence did not support her story, and a coroner’s inquest ordered her arrest on the charge of manslaughter. A grand jury indicted her, but she was eventually acquitted at trial in March 1906.

After a week of mourning and taking care of family business, Ty Cobb rejoined his team. Before the month was out the Tigers exercised their option, and purchased Cobb for $700. Normally this would have been a great moment, the realization of a dream, but the shadow of the tragedy hung over the teenager. In his autobiography, Cobb wrote “In my grief, it didn’t matter much…I only thought, Father won’t know it.”

Cobb made his big league debut on August 30, 1905. He appeared in 41 games that season, compiling a modest .240 batting average. However, he was treated very poorly by his teammates, who gave him the typical rookie hazing. Given Cobb’s state of grief, and the fact that this was his first time out of the South, he was unable to deal with the hazing, which led to resentments with his teammates that lasted many years.

The 1906 season was difficult for Cobb from the outset. In spring training, while his mother’s trial was ongoing, he continued to feud with his teammates. Cobb found his hats ruined, and his bats cut. In his autobiography, Cobb described the ostracism and hazing by his teammates as “the most miserable and humiliating experience I’ve ever been through.”

On the field, Cobb played well, winning the center field job against strong competition. However, the stress wore him down, and he was out of the lineup the second half of July and all of August with what may have been an emotional and physical collapse. He returned in September, and finished the season with a .316 batting average in 98 games.

These events of 1905 and 1906 changed Cobb forever. Already strong willed and competitive, Cobb became a loner, at war with the world. And while his relations with teammates eventually improved, and while Cobb did make some lasting friendships, his will to succeed at any cost never changed. Late in life, when asked by Al Stump why he fought so hard in baseball, Cobb explained “I did it for my father…I knew he was watching me and I never let him down.”

The 1907 season marked Cobb’s arrival as a superstar. The Georgian led the league in hits, RBI, and batting average, carrying the Tigers to their first American League pennant. He and the team repeated the performance the next two seasons, and Cobb added his only home run title in 1909 to take the Triple Crown. He also led the league in stolen bases in 1907 and 1909. The Tigers lost all three World Series, the first two to the powerful Chicago Cubs, and the last one in a seven-game thriller to the Pittsburgh Pirates. In the 17 Series games, Cobb had an undistinguished .262 batting average with 9 RBI and four stolen bases. These were the only three World Series in which the Georgian would appear.

During this period Cobb began to develop a reputation for controversy. In August of 1908, he left the team for six days in the middle of a tight pennant race to marry Charlie Lombard, heiress to a $300,000 fortune, in Augusta. In August of 1909, Cobb slid into third on a close play, cutting the arm of Philadelphia Athletics third baseman Frank Baker. Although Cobb was within his rights, emotions ran high in Philadelphia, and Cobb received death threats when the Tigers played in Philadelphia in mid-September. Meanwhile, in a more serious matter, Cobb got into a fight in Cleveland with George Stanfield, a hotel night watchman who was African-American. In the aftermath, a warrant was issued for Cobb’s arrest on the charge of attempted murder — which he avoided by fleeing town — and Stanfield launched a civil suit. The criminal charges were settled after the season with Cobb pleading guilty to a lesser charge, and the civil suit was settled out of court.

During and after his career, Ty Cobb was involved in a number of violent altercations. Some of the best known of these incidents were with African-Americans. In 1908 Cobb had been arrested for assaulting an automobilist in a road rage incident, and in 1924 he pummeled a ticket taker at Shibe Park; in each case Cobb claimed that his African-American victim had “insulted” him. In recent years, Cobb’s racial attitudes have seemed to diminish his reputation.

Cobb certainly did not oppose racial segregation in baseball or elsewhere, and all evidence shows that his attitudes were typical of his times and Georgia upbringing. Years later he took a somewhat different view, however. In an Associated Press article dated January 29, 1952, Cobb came out in favor of integration in baseball, stating “Certainly it is O.K. for them to play. I see no reason in the world why we shouldn’t compete with colored athletes as long as they conduct themselves with politeness and gentility.” Later, Cobb wrote to Al Stump that segregation was a “lousy rule.”

Cobb’s style of play relied more on strategy, daring, and quick thinking than pure talent. He was always one step ahead of the opposition, doing the unexpected, especially on the base paths. In The Glory Of Their Times, Larry Ritter quoted Sam Crawford, who didn’t like Cobb, as saying “He didn’t outhit the opposition and he didn’t outrun them. He outthought them!” Cobb dominated the Deadball Era both through his performance and his style of play. Runs were hard to come by, and Cobb was always looking for an edge. At bat, he studied pitchers, learning their weaknesses. On the base paths he was always the aggressor, trying to create opportunities. Cobb later told of how he sometimes ran the bases recklessly in one-sided games to plant fear in the minds of the opposition, which led to errors in close games where a momentary hesitation by an opposing fielder could prove decisive. When on the bases, Cobb would kick the bag — not because it was a habit, which everyone assumed, but because by kicking it toward the next base he could pick up a few precious inches if he decided to steal a base.

By 1910 Cobb was recognized as the biggest star in the American League. However, he remained unpopular with his teammates and opposing players for his attitude and rugged style of play. This led to another major controversy — an attempt to fix the 1910 American League batting title. Cobb and Cleveland’s popular star Napoleon “Larry” Lajoie were locked in a tight race for the AL crown. Cobb sat out the final two games of the season in order to preserve his lead. But Browns manager Jack “Peach Pie” O’Connor, who hated Cobb, decided to make sure that Lajoie caught Cobb in a season-ending doubleheader between St. Louis and Cleveland, by ordering rookie third baseman Red Corriden to “play back on the edge of the [outfield] grass.” Lajoie responded by dumping seven bunt singles down the third base line, as part of an 8-for-8 day that seemingly gave him the title.

Cobb’s teammates wired Lajoie their congratulations, but the press railed against the obvious fraud. American League President Ban Johnson investigated the matter but, in typical fashion for baseball officials of that day, decided to sweep the scandal under the rug. However, the official figures showed that Cobb had won the batting championship, thanks to one game’s results being counted twice. The clerical error was discovered years later, and who should be considered the 1910 AL batting champion is still a matter of controversy. Lajoie has the higher average, but Cobb is still recognized by Major League Baseball as the official batting champion.

Another major controversy in Cobb’s career occurred in 1912, and this led to the first players’ strike. During a game in New York on May 15 of that year, Cobb was subjected to vicious and unrelenting heckling from the fans, especially a disabled man named Claude Lueker, who for several years had made sport of heckling Cobb whenever the Tigers visited Hilltop Park. Finally, unable to stand the abuse and urged on by his teammates, Cobb went into the stands and attacked Lueker, who had lost one hand and most of the other in a printing press accident. When he was informed of the incident, Ban Johnson suspended Cobb indefinitely. Despite their dislike for Cobb, his teammates were outraged, and announced that they would not play again until Cobb was reinstated. After a one-game farce in which the Tigers fielded a team of semipro players, the matter was resolved when Cobb’s suspension was reduced to ten days.

Cobb continued to excel on the field throughout the decade, clearly becoming the game’s dominant player, and in the opinion of most contemporaries the greatest player in baseball history. The 1911 season was one of his finest, as he batted .420 and led the league in runs, hits, doubles, triples, RBI, slugging percentage, and stolen bases. He regularly led the league in batting, and was at or near the top of most offensive categories.

In addition to his success on the field, the second decade of the twentieth century brought economic affluence to Ty Cobb. He was the game’s highest paid player, aided by his almost annual holdouts and the 1914-15 Federal League war. Cobb made money on investments also, including investing in cotton in the commodities market, and became an early investor in Coca-Cola and United Motors (which later merged with General Motors). Cobb’s investments made him a rich man. Cobb’s fortune at the time of his death was estimated at $12 million.

Despite Cobb’s continued excellence, the Tigers generally finished far out of first place after 1909. Detroit fans and management wanted Cobb to succeed his long-time friend and boss, Hughey Jennings. Finally, in 1921 Cobb accepted, and became the player-manager of the Tigers. The team improved under Cobb, but other than in 1924 the Tigers were not a real factor in the pennant race under his leadership. However, he did have a great deal to do with the development of Tigers hitters, especially future Hall of Famer Harry Heilmann.

In 1926 the Tigers fell to sixth place in the American League, but they had a respectable 79-75 record. So it was a surprise when, on November 3, 1926, Cobb announced that he was stepping down as manager of the Tigers and retiring from baseball. Soon thereafter, player-manager Tris Speaker of the second place Cleveland Indians announced that he was also stepping down, and retiring from the game. A few weeks later, the reason was made public–former Detroit pitcher Hubert “Dutch” Leonard claimed that he, Cobb, Speaker, and Cleveland outfielder Joe Wood had fixed a game between Detroit and Cleveland on September 25, 1919.

Had it only been the word of Leonard, it is unlikely that the charge would have been taken seriously. Cobb, who was supposed to benefit from the fix, went only 1-for-5, albeit with two runs scored and two steals, while Speaker, supposedly throwing the game, had three hits in five trips to the plate, including two triples. Wood and Leonard did not play. However, Leonard supplied two letters written to him in the fall of 1919, one from Wood which clearly indicates that bets were placed, although he states that Cobb did not bet, and one from Cobb himself, indicating that an attempt to bet was made, but that it didn’t work out.

While there was strong evidence that bets were placed or, in the case of Cobb, a bet was attempted, there was no evidence of a fix other than Leonard’s word, and he refused to travel to Chicago to face Cobb and Speaker at a hearing. It was also common knowledge that Leonard nursed a grudge against the two stars. On January 27, 1927, Commissioner Landis ruled that Cobb and Speaker were not guilty, stating “These players have not been, nor are they now, found guilty of fixing a ball game. By no decent system of justice could such finding be made.”

In the aftermath, Cobb threatened a lawsuit, and enlisted the help of several prominent politicians to launch an investigation into organized baseball. But when Cobb received a lucrative offer from Philadelphia owner and manager Connie Mack, one of the few men in baseball that Cobb truly admired and respected, Ty agreed to join the Athletics, playing with that club for two seasons before announcing his retirement.

Cobb’s life after baseball was less rewarding than his career as a player. Secure financially, he led a life of leisure, but his family life was less than ideal. After a number of break-ups, he and Charlie Cobb were divorced in 1947, and Cobb’s relationship with his five children was strained. He married Frances Fairbairn in late 1949, but by 1956 this marriage also ended in divorce.

Ty Cobb’s health began to fail him in the late 1950s, and he became an alcoholic. Realizing that he was in decline, he finally agreed to do what he had always refused to consider: write his autobiography. He teamed up with Al Stump on My Life In Baseball — The True Record, which was published posthumously. In summing up his life to Stump, Cobb stated “I had to fight all my life to survive. They all were against me , tried every dirty trick to cut me down. But I beat the bastards and left them in the ditch.”

Ty Cobb died at age 74 on July 17, 1961 in Emory Hospital in Atlanta, of prostate cancer. He was buried in Rose Hill Cemetery in his hometown of Royston, beside his parents and his sister.

An earlier version of this biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., “Deadball Stars of the American League” (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

Al Stump. “Ty Cobb’s Wild Ten Month Fight To Live.” Reprinted in The Third Fireside Book of Baseball, edited by Charles Einstein. Simon and Schuster, 1968.

Ty Cobb and Al Stump. My Life in Baseball — The True Record. Doubleday & Co., 1961.

Charles Alexander. Ty Cobb Oxford University Press, 1984. Page 19.

Ty Cobb Scrapbook, housed at the Elliott Museum, Stuart, FL.

Daniel Ginsburg. The Fix Is In. McFarland & Co., 1995.

Full Name

Tyrus Raymond Cobb

Born

December 18, 1886 at Narrows, GA (USA)

Died

July 17, 1961 at Atlanta, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.