Bob Hope

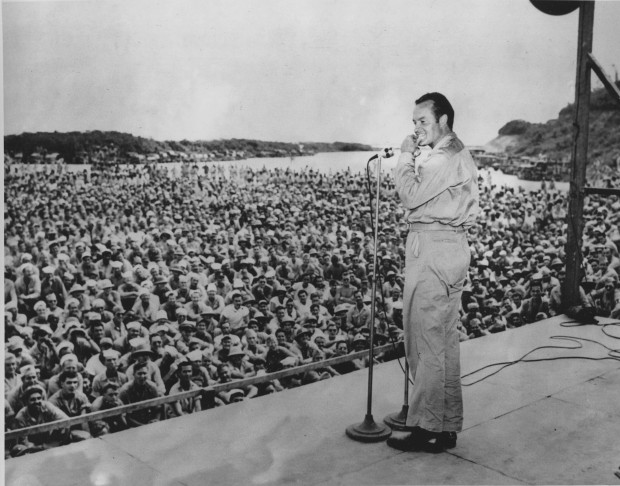

Bob Hope entertained troops in war zones, hosted the Academy Awards 19 times, and had more wealth than Midas thanks to oil investments, real estate holdings, and television commercials for Texaco and Chrysler. His relationship with NBC, unparalleled in show business, started on radio in the 1930s and continued on television when it became a household item in the late 1940s. Hope became as much a trademark of the network as its famed peacock. Bob Hope specials aired every few months until the early 1990s.

Bob Hope entertained troops in war zones, hosted the Academy Awards 19 times, and had more wealth than Midas thanks to oil investments, real estate holdings, and television commercials for Texaco and Chrysler. His relationship with NBC, unparalleled in show business, started on radio in the 1930s and continued on television when it became a household item in the late 1940s. Hope became as much a trademark of the network as its famed peacock. Bob Hope specials aired every few months until the early 1990s.

But the heights of fame, glory, and accolades never obscured, even slightly, Hope’s affection for his hometown — Cleveland. On October 3, 1993, Hope, who began his career in vaudeville 70 years before, sang a customized version of his trademark song “Thanks for the Memory” at Municipal Stadium to lead the city’s farewell to the beloved baseball edifice. The Indians were blanked, 4-0, by the White Sox that afternoon, but Hope’s appearance was more salient than the score.

“If you’re a Clevelander, you always had the connection to Bob Hope,” says former Indians play-by-play announcer Jack Corrigan, a hometown guy who called games on WUAB-TV in 1983 and 1985-2001. “Our family had a connection to him — my grandparents had mutual friends with his family. He spoke lovingly of the city in his appearances. So, we all thought that it was pretty special when we heard he would do the sendoff.”1

Hope was more than a fan bonded to his hometown team — he had two stints as a part owner for decades. In 1946, he joined Bill Veeck’s group to purchase the Indians. “My interest in the deal was purely sentimental, as I am a former resident of Cleveland,” said Hope. “Of course, I have no interest — ahem — in any money we might make out of the club.”2 An opportunity had been presented the year before, but it never reached the deal-making phase.3 In 1963, he became a member of the team’s board of directors.4

It was a fact that he often highlighted. In 1947, Hope joined Bing Crosby, often his co-star in movies and a part-owner of the Pittsburgh Pirates, for a comedy bit during Spring Training. “Baseball’s Bustin’ Out All Over” was part of the Paramount News offerings shown before movies. It features Hope and Crosby wearing their individual team garbs, tossing a baseball, and joking about contract holdouts.5 Hope showed up at the Indians’ 1949 Spring Training camp in Tucson, Arizona, for laughs and took a swing with an oversized bat that Goliath might have used if David was pitching.6

In 1963, Sports Illustrated gave the cover story to the comedian: “Hope: All Kinds of a Nut About Sports.” In addition to the stake in the Indians, SI writer Jack Olsen underscores Hope’s commitment bordering on fanaticism. But Hope was not the average fan limited to radio, television, and newspapers for information. Wealth allowed access. “He is the kind of sports nut who will interrupt a visit to New Orleans to fly to Cincinnati to play a round of golf with some cronies,” wrote Olsen. “He has been a fighter, a sprinter, a pool hustler, a four-handicap golfer, a professional football team’s mascot and a holder of substantial shares of stock in enterprises such as the Los Angeles Rams and the Cleveland Indians. He seldom misses a big fight, even if he has to rush over to the Pantages Theater in Hollywood to see it on theater TV. He has played something between 1,000 and 1,500 golf courses, in such varied places as Brazil and Greenland, in company with anteaters, monkeys and, sometimes, Presidents.”7

Hope was born on May 29, 1903, in the Greater London area. An American comedy treasure, Hope emigrated from England at the age of four with his parents, William Henry Hope and Avis Hope, and six brothers. “I left England because I knew there was very little chance of me becoming king,”8 joked Hope in a 1972 interview with Dick Cavett. As a teenager, he fought under the name “Packy East” around Cleveland. It was, according to Hope, a futile vocation. “I fought as Rembrandt East for a while. I was on the canvas so much.”9

Originally named Leslie Townes Hope, he changed his name to Bob, a moniker with an everyday aura, while pursuing a performing career in vaudeville. This form of entertainment began to fade with the ascendance of radio and talking pictures in the 1930s. “What Hope had been through was thirteen years of vaudeville, which taught the lessons of free enterprise: thrift, self-reliance, perseverance, innovation, and ruthlessness,” explained John Lahr in a 1998 retrospective for The New Yorker. “It was a paradigm of Darwinian struggle, in which only the fittest performers survived the schedule, the audiences, and one another.”10

Hope’s emergence as a star began with a starring role in the Broadway musical comedy Roberta in 1933. Noted critic Brooks Atkinson was none too kind. “The humors of ‘Roberta’ are no great shakes, and most of them are smugly declaimed by Bob Hope, who insists upon being the life of the party and who would be more amusing if he were Fred Allen.”11

Other reviewers found Hope to be praiseworthy. The Brooklyn Citizen lauded him: “Bob Hope, one of the most likeable persons on the stage to-day, dominates every scene in which he appears. He has a pleasing personality and puts a song across in such a manner as to make it click instantly.”12 The Daily News stated that Hope “gives cheerily of his late-spot pleasantries”13 while the Brooklyn Daily Eagle noted his “able clowning.”14

Before Paramount’s The Big Broadcast of 1938, Hope’s Hollywood career had consisted of short films. Then his on-screen partnership with Bing Crosby and Dorothy Lamour in the “Road to…” movies solidified him as a bankable star. But it was Hope’s connection to NBC that made him a popular-culture icon with a place on the Mount Rushmore of comedy. It began on NBC’s radio network in 1934; Hope’s affection for sports led to a smooth on-air rapport jousting with guest stars such as Babe Ruth15 and Dizzy Dean.16 In a 1950 episode, the Indians were in the radio audience. Their boss made them the target of his wit: “But the boys look good to me. These boys have taken off so much weight in Spring Training, yesterday, Lou] Boudreau slid into third and his uniform was just rounding second.”17

But Hope was able to break away from NBC for an occasional guest spot for a rival. He emceed the first broadcast for independent television station KTLA (Los Angeles) on January 22, 1947. “It is a thrill being here because television I understand is a combination of radio and pictures. This is a little medium that Crosby invented so he could steal the money without even leaving the house.”18 A baseball skit featured an actor pantomiming pitching a game for the New York Giants, but getting pulled after giving up a line drive. The background music is “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” Hope broke ranks with NBC again in 1974 when he did a cameo on ABC’s The Odd Couple because of a “great friendship with Tony Randall.”19 While taking out his garbage, he has a chance encounter with star-struck photographer Felix Unger (Tony Randall) and his roommate, New York Herald sportswriter Oscar Madison (Jack Klugman), who’s in Hollywood to do his own cameo in a baseball movie with fellow scribes.20

Hope’s well-known friendship with fellow comedy icon Lucille Ball was manifested in a guest spot as himself on the season premiere of I Love Lucy in 1956.21 In a paradigm typical of the CBS show, Lucy Ricardo wants to perform at the nightclub owned by her husband, Cuban-born singer and bandleader Ricky Ricardo, who bought his place of employment — Tropicana — and changed the name to Club Babalu. Ricky signs Hope for opening night. Lucy, always determined, tracks Hope to Yankee Stadium, where the Indians are playing the Yankees. Disguised as a vendor, Lucy overwhelms the comedian, as she is apt to do, and he misses third baseman Al Rosen hitting a home run. (An entire season of I Love Lucy was set in Hollywood, where she had hilarious encounters with entertainment’s elite, including John Wayne,22 Harpo Marx,23 and William Holden24.)

There is a touch of truth to the scene. Rosen homered in two Indians-Yankees contests at Yankee Stadium in 1956, on May 9 (Indians won, 6-5) and June 8 (Indians won, 9-0). It’s plausible that the May 9 game is the one described because Rosen went yard in the first inning — a solo shot off Don Larsen after the pitcher retired Jim Busby and Bobby Avila — and Hope would likely have arrived at the start of the game.

Lucy’s shenanigans also lead to a foul ball hitting Hope on the head. Continuing her ruse, Lucy masquerades as an Indians player, wearing Bob Feller’s 19 and a cap depicting what appears to be a studio-made, though distorted, version of Chief Wahoo. Ricky visits Hope, who is nursing his noggin in the Indians locker room, and alerts him to Lucy’s zaniness. Though Ricky reveals the ballplayer to be Lucy, she convinces Hope through tears and heartbreak that she belongs on stage. Dressed as umpires, the trio sings “Nobody Loves the Ump” and Hope dances a soft shoe routine, then sings his trademark song, “Thanks for the Memories,” and Desi sings in Spanish. There’s an obvious chemistry between the stars. Hope jokes, “I may never go back to NBC.”

Later that month, Hope welcomed Don Larsen after the hurler’s perfect game against the Brooklyn Dodgers in the World Series. Hope asks Larsen if he’s ever seen Little Leaguers in action. Larsen’s response: “Sure, Bob. We played Cleveland.”25 The joke is factually unsound. Though the Yankees were dominant that year with a 97-57 record, Cleveland had a respectable 88-66 tally, good enough for second place in the American League. Larsen recreated the last out of the perfect game — a strikeout of Dale Mitchell.

In the 1963 movie Critic’s Choice, Hope teamed up with Ball again. He portrays a New York City theater critic with a son, bordering on adolescence but wiser than his years, from his first marriage to an actress whom he recently panned. Ball plays his second wife, an aspiring playwright. One scene has a father-son baseball game with Hope playing second base. During Major League Baseball’s Centennial in 1969, Chrysler bought space for print advertisements and put its most famous spokesman in cartoon form, wearing his Indians uniform with a question mark in place of a number. Hope has a dialogue bubble: “Make a hit with the whole family…with a new car from Chrysler Corporation.”26 Elsewhere in the ad are players and an umpire touting Chrysler’s array of models: Plymouth, Dodge, Imperial, Simca, Sunbeam, and, of course, Chrysler. Just a few months before, Hope’s ownership concern in the Indians teetered towards a sale when the comedian considered buying the second incarnation of the Washington Senators (1961-1971). The purchase, which had a reported price tag of $10.5 million,27 would have required Hope to sever his ten percent ownership in his hometown nine. Hope did not exercise his option. “I am still interested in buying the team, but we have to work out a few things.”28 Bob Short, a politically-connected businessman and treasurer of the Democratic National Committee, bought the team for $9 million29 and kept the Senators inside the Beltway for three seasons, then moved to the Lone Star State as the Texas Rangers.

Hope’s baseball connection furthered in the 1978 NBC special Bob Hope’s All-Star Comedy Salute to the 75th Anniversary of the World Series featuring baseball-themed comedy sketches, film clips, and one-liners. The roster of guests is a Who’s Who of late 1970s stardom: Cheryl Tiegs, Billy Martin, Glen Campbell, Charo, Kermit the Frog and Miss Piggy, and Steve Martin, who was just beginning his ascent to icon status. ABC sportscaster Howard Cosell crossed the invisible boundary separating networks to appear on the program.30

Danny Kaye, himself a part-owner of the Seattle Mariners, joins Hope as an informal co-host. Film clips include Hope’s live appearances with Vida Blue and Johnny Bench; the song “Nobody Does It Better” as a backdrop for a baseball bloopers montage; and a 1963 segment showcasing Don Drysdale, Sandy Koufax, and Tommy Davis after their four-game sweep of the Yankees in the World Series. The trio wears white tie and tails, banters with Hope, and sings custom-made lyrics of “We’re in the Money.”

Though his connection to baseball was formidable, Hope became synonymous with golf. The Palm Springs Desert Classic, which originated in 1952 as the Thunderbird Invitational Pro-Am, changed its name to the geographical moniker in 1959, then in 1965 to the Bob Hope Desert Classic. In 2019, he became one of three inaugural members of the tournament’s Hall of Fame, along with Arnold Palmer — who won the tournament five times — and original tournament board member Ernie Dunlevie.31 Such was Hope’s imprint on the game that he was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame in 1983. “I couldn’t believe it when they notified me,” said Hope two years later. “It was almost like inducting John McEnroe into the Diplomatic Hall of Fame. I’ve done about as much for golf as Truman Capote has for sumo wrestling.”32 It was a remark typical of Hope’s self-deprecating humor, but nonetheless a false one. Hope incorporated golf into the nation’s zeitgeist for a post-World War II generation elevated by well-earned prosperity and hungry for middle-class leisure. It was common for Hope to brandish a golf club during his dozens of USO performances for soldiers overseas. “He brought it to mainstream,” said Tiger Woods. “He brought it to the masses. I think with their affiliation together, Arnold [Palmer] as well as Bob, they did a tremendous job of doing that. It couldn’t have happened at a better time in popularizing our game.”33

Though his connection to baseball was formidable, Hope became synonymous with golf. The Palm Springs Desert Classic, which originated in 1952 as the Thunderbird Invitational Pro-Am, changed its name to the geographical moniker in 1959, then in 1965 to the Bob Hope Desert Classic. In 2019, he became one of three inaugural members of the tournament’s Hall of Fame, along with Arnold Palmer — who won the tournament five times — and original tournament board member Ernie Dunlevie.31 Such was Hope’s imprint on the game that he was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame in 1983. “I couldn’t believe it when they notified me,” said Hope two years later. “It was almost like inducting John McEnroe into the Diplomatic Hall of Fame. I’ve done about as much for golf as Truman Capote has for sumo wrestling.”32 It was a remark typical of Hope’s self-deprecating humor, but nonetheless a false one. Hope incorporated golf into the nation’s zeitgeist for a post-World War II generation elevated by well-earned prosperity and hungry for middle-class leisure. It was common for Hope to brandish a golf club during his dozens of USO performances for soldiers overseas. “He brought it to mainstream,” said Tiger Woods. “He brought it to the masses. I think with their affiliation together, Arnold [Palmer] as well as Bob, they did a tremendous job of doing that. It couldn’t have happened at a better time in popularizing our game.”33

At the age of two, Woods met Hope in a foreshadowing of the former’s excellence. Earl Woods brought his son to The Mike Douglas Show, where Tiger showed prowess at hitting a golf ball while most of his peers were mastering blocks.34

“Bob’s favorite sport to watch was golf because he played it,” says Hope’s archivist and producer Jim Hardy, who began working for the comedian in 1986 and continues preserving his entertainment archives. “He always carved out time on the weekends. Bob’s favorite athlete was Arnold Palmer because he was the first pro golfer that he really forged a friendship with. Arnold had a great sense of humor, too. He would needle Bob after a putt missed the hole. But Bob’s favorite event that he attended was the 1948 World Series. When he was a kid in Cleveland, he watched games through the fence. His favorite player was Tris Speaker.

“Bob had a genuine admiration for what athletes do and it was clear in his performances with them. Audiences really responded to that. You can’t fake it. There was a time when we didn’t know anything about our sports heroes. Bob brought them to a national audience through radio and television so they could show their humor and personality. They also went with him on goodwill trips to visit military bases, where Bob had a great relationship with military personnel. He cared about the soldiers and they knew it.”35

Hope’s specials with NBC were a television staple in the latter half of the 20th century,and the sporting world was a cornerstone for comedy. Just a few samples: Bob Hope’s Stand Up and Cheer for the National Football League’s 60th Year. Bob Hope’s All-Star Super Bowl Party. The Bob Hope Special: The Opening of the New Madison Square Garden. After the 1968 Tigers-Cardinals World Series, Hope brought the season’s leading pitchers, Denny McLain (31-6) and Bob Gibson (1.12 ERA), on The Bob Hope Show.36 His last special was in 1996 — Laughing with the Presidents.

Honors for Hope include cargo ship USNS Bob Hope; Air Force plane The Spirit of Bob Hope; Bob Hope Airport in Burbank; Bob Hope Patriotic Hall in Los Angeles; Bob Hope Drive in Burbank and Rancho Mirage; the Congressional Gold Medal; Kennedy Center Honors; Presidential Medal of Freedom; and Department of Defense Medal for Distinguished Public Service. Though he had the comportment required to dine, joke, and golf with heads of state, it seems that Bob Hope was most comfortable when he performed, whether at a military base in Da Nang or an NBC studio in Burbank.

Hope passed away on July 27, 2003, survived by his wife, Dolores, and four children — Kelly, Nora, Linda, and Tony. The Hopes adopted the children and were surrogate parents to Tracey Shor, the youngest child of legendary restaurateur Toots Shor and his wife, Marion.

One thought develops when coming across clips of his performances from newsreels, radio, movies, live performances, or television shows: thanks for the memories, Bob.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Phil Williams and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 Jack Corrigan, telephone interview with writer, December 23, 2018.

2 Carl T. Felker, “Contacted Last Year on Deal for Indians, Hope Discloses,” The Sporting News, July 10, 1946: 11.

3 Felker

4 Hal Lebovitz, “Derrick Hurler? Wait — Let’s Have Board Vote on It,” The Sporting News, March 23, 1963: 1.

5 “Baseball’s Bustin’ Out All Over,” Paramount News, 1947.

6 “Indians In Arizona,” Warner Pathe News, 1949.

7 Jack Olsen, “Hope: All Kinds of a Nut About Sports,” Sports Illustrated, June 3, 1963, 66.

8 The Dick Cavett Show, ABC, October 4, 1972.

9 Cavett

10 John Lahr, “The C.E.O. of Comedy,” The New Yorker, December 21, 1998, 68.

11 Brooks Atkinson, “The Play: Fashions for Women in a Musical Comedy by Jerome Kern and Otto Harbach,” New York Times, November 20, 1933: 18.

12 “The Premiere,” Brooklyn Citizen, November 20, 1933: 14.

13 Burns Mantle, “‘Roberta,’ With Handsome Gowns and Tunes,” Daily News (New York), November 20, 1933: 34.

14 Art Arthur, “Reverting to Type,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 18, 1933: 13.

15 The Bob Hope Show, NBC (radio), March 3, 1942.

16 The Bob Hope Show, NBC (radio), March 11, 1941

17 The Bob Hope Show, NBC (radio), March 21, 1950.

18 First Broadcast, KTLA, January 22, 1947.

19 Jim Hardy, telephone interview with writer, June 21, 2019.

20 The Odd Couple, “The Hollywood Story,” ABC, October 3, 1974, Hal Goldman and Al Gordon.

21 I Love Lucy, “Lucy and Bob Hope,” CBS, October 1, 1956, Madelyn Davis, Bob Carroll, Jr., Bob Schiller, Bob Weiskopf. (An entire season of I Love Lucy was set in Hollywood, where she had hilarious encounters with entertainment’s elite, including John Wayne, Harpo Marx, and William Holden.)

22 I Love Lucy, “Lucy Visits Grauman’s,” CBS, October 3, 1955, Jess Oppenheimer, Madelyn Pugh, Bob Carroll, Jr., Bob Schiller, Bob Weiskopf; I Love Lucy, “Lucy and John Wayne,” CBS, October 10, 1955, Jess Oppenheimer, Madelyn Pugh, Bob Carroll, Jr., Bob Schiller, Bob Weiskopf.

23 I Love Lucy, “Lucy and Harpo Marx,” CBS, May 9, 1955, Jess Oppenheimer, Madelyn Davis, Bob Carroll, Jr.

24 I Love Lucy, “Hollywood at Last,” CBS, February 7, 1955, Jess Oppenheimer, Madelyn Pugh, Bob Carroll, Jr.

25 The Bob Hope Show, NBC, October 21, 1956, Mort Lachman, Bill Larkin, Charles Lee, John Rapp, Lester A. White.

26 Print advertisement, Chrysler Corporation, 1969.

27 Shirley Povich, “Bob Hope Enters Bidding for Nats,” Washington Post, November 7, 1968: L1.

28 Shirley Povich, “Senators’ Sale, Price Lower, Tips Toward Short,” Washington Post, November 22, 1968: D1.

29 Shirley Povich, “Senators Are Sold To Short,” Washington Post, December 4, 1968: A1.

30 Bob Hope’s All-Star Comedy Salute to the 75th Anniversary of the World Series, NBC, October 15, 1978.

31 Larry Bohannan, “Bob Hope, Arnold Palmer headline inaugural Desert Classic Hall of Fame Class,” Palm Springs Desert Sun, https://www.desertsun.com/story/sports/golf/careerbuilder/2019/01/15/pga-tour-desert-classic-names-bob-hope-arnold-palmer-ernie-dunlevie-hall-fame/2553935002/, January 15, 2019.

32 Dave Anderson, “Bob Hope a Maestro With Golf, Guffaws,” Palm Beach Post, January 13, 1985: 475.

33 100 Years of Hope and Humor, NBC, April 20, 2003, Linda Hope and Steve Feld.

34 The Mike Douglas Show, Syndicated, October 6, 1978.

35 Jim Hardy, telephone interview with writer.

36 The Bob Hope Show, NBC, October 14, 1968.

Full Name

Leslie Townes Hope

Born

May 29, 1903 at Eltham, Kent (ENG)

Died

July 27, 2003 at Toluca Lake, CA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.