Don Larsen

He was a bundle of contradictions, this imperfect man who pitched a perfect game. Don Larsen disdained training rules and had a mediocre major-league career; yet he pitched the greatest game in World Series history. He married out of a sense of duty; yet he refused to support his wife and baby daughter. He kept his marriage secret as long as he could, preferring to be viewed as a carefree bachelor. He loved the night life; yet he lived out his retirement years in a quiet village in northern Idaho, far from the crowded bars of his youth. This man who turned down college scholarships because he didn’t like to study, the same man who had to be compelled by a court order to support his family, auctioned off one of his most prized possessions to raise money to support his grandchildren’s college education. Don Larsen was truly a bundle of contradictions.

He was a bundle of contradictions, this imperfect man who pitched a perfect game. Don Larsen disdained training rules and had a mediocre major-league career; yet he pitched the greatest game in World Series history. He married out of a sense of duty; yet he refused to support his wife and baby daughter. He kept his marriage secret as long as he could, preferring to be viewed as a carefree bachelor. He loved the night life; yet he lived out his retirement years in a quiet village in northern Idaho, far from the crowded bars of his youth. This man who turned down college scholarships because he didn’t like to study, the same man who had to be compelled by a court order to support his family, auctioned off one of his most prized possessions to raise money to support his grandchildren’s college education. Don Larsen was truly a bundle of contradictions.

Don James Larsen was born on August 7, 1929, in Michigan City, on the shores of Lake Michigan in extreme northwestern Indiana. He was the second child and only son of Charlotte and James Larsen. During his childhood his mother worked as a waitress in a restaurant, His father, son of Norwegian immigrants, was a watchmaker in a retail jewelry store. Years later Don Larsen remembered, “My first introduction to baseball was watching my father play sandlot ball.”1 When he was 4 years old Don started playing baseball with his father. James encouraged Don in his childhood ambition to become a professional baseball player. However, the youngster showed more talent in basketball than baseball. As a freshman, Don made the Michigan City High School basketball team.

In 1944 Don moved with his family to San Diego, where his mother worked as a housekeeper in a retirement home and his father became a jewelry salesman. At Point Loma High School Don became a star in basketball and baseball. He made the All-Metro Conference basketball team and received several scholarship offers to play college basketball, which he declined. He said, “I was never much with studies, and I didn’t really have an interest in going to college and studying my life away.”2 Art Schwartz, a scout for the St. Louis Browns, saw Larsen pitching for an American Legion team and offered him a contract. He signed for an $850 bonus.

The Browns sent the 17-year-old right-handed pitcher to Aberdeen in the Class-C Northern League. Larsen pitched two seasons for the Pheasants, winning four games in 1947 and 17 in 1948. He started the 1949 season with the Globe-Miami Browns in the Class-C Arizona-Texas League and was promoted in midseason to Springfield in the Class-B Three-I League. Another promotion came in 1950, as he moved from the Wichita Falls Spudders in the Class-B Big State League to the Wichita Indians in the Class-A Western League. He was described by Bob Turley, one of his teammates in both the minors and majors, as a “fun-loving guy who liked to go out and have a beer or two and talk to people in bars.”3

In 1951 Larsen was drafted into the US Army. He spent two years during the Korean War in noncombat roles. After basic training at Fort Ord, he was sent to Hawaii. When an officer learned that Larsen was a professional baseball player, he assigned him to a Special Services unit at Fort Shafter. He pitched and played first base for an Army team during 1951 and 1952. Corporal Larsen was discharged in 1953 and went to spring training in 1953 on the roster of the San Antonio Browns. After several good pitching performances, he was promoted to the big-league Browns. “I’ll never forget how excited I was when I found out I made the club,” he said. “It was like Christmas in springtime.”4

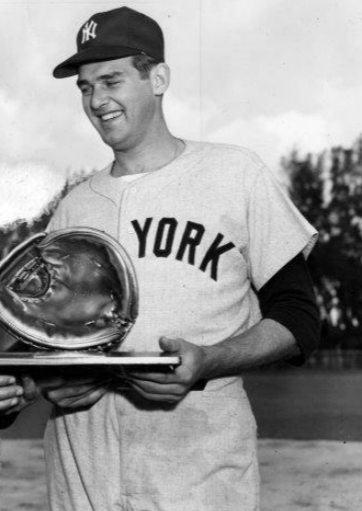

The 23-year-old stood 6-feet-4 and weighed 215 pounds. His teammates gave him the nickname Gooney Bird. Writer Lew Paper said it was because of his protruding ears, pear-shaped body, and long, dangling arms.5 Another writer, Peter Golenbock, said the nickname was bestowed because of Larsen’s antics.6

Larsen made his major-league debut on Saturday, April 18, 1953, in the first game of a doubleheader against the Detroit Tigers at Briggs Stadium. The first batter he faced, Harvey Kuenn, touched him for a single, but he settled down and pitched shutout ball for five innings. He was knocked out of the box in the sixth, as the Tigers scored three runs to take a 3-2 lead. However, the Browns rallied to win the game, 8-7, with Larsen receiving no decision. He collected his first major-league win at Connie Mack Stadium on May 12, pitching 7⅔ innings and giving up one earned run in the Browns’ 7-3 win over the Philadelphia Athletics.

The Browns moved to Baltimore in 1954. That season Larsen led the league in losses with 21, while winning only three games, but fortunately for him two of the wins were over the New York Yankees, and Yankees manager Casey Stengel remembered those two wins. Larsen did not honor the midnight curfew set by the Browns. His motto was, “Let the good times roll. You give the best you can on the field. Who cares what you do afterwards, as long as you show up and do well.”7 Jimmy Dykes, his manager in Baltimore, said, “The only thing Don fears is sleep.”8

During the season Larsen met the future Vivian Larsen, a 27-year-old telephone operator in Baltimore. At the end of the season he intended to break off the affair, but Vivian called him in California and told him she was pregnant. Abortion was out of the question. Larsen suggested she put the baby up for adoption. She refused. Vivian was determined to keep the baby. Larsen then did what he thought was the honorable thing. They were married on April 23, 1955. Don insisted that the marriage be kept secret; he was marrying her only for the sake of the child. Three months later he left her with no intention of returning because he was not ready to settle down and preferred “a life of free and easy existence.”9

Larsen was traded to the New York Yankees on November 17, 1954, in a huge transaction involving 17 players. He reported to spring training in 1955 with a sore shoulder and was soon sent down to the Yankees’ farm club in Denver. He won 9 of 10 decisions for the Bears and after four months in the Triple-A American Association, he was recalled to New York. Between New York and Denver he had won 18 games that year, against only three losses. One of his teammates said, “He probably had a lot more ability than 95 percent of all the pitchers in baseball, He was a good hitter. He could run the bases. He could field the ball. But he was a lazy type.”10

The Yankees won the American League pennant in 1955 and faced the Brooklyn Dodgers in the World Series. The Dodgers were playing in Brooklyn’s eighth World Series. They had seven losses to show for their first seven attempts. The Ebbets Field faithful were hoping for a different outcome in 1955. The Dodgers were a powerful club, featuring four future Hall of Famers — Roy Campanella, Pee Wee Reese, Jackie Robinson, and Duke Snider — plus perennial all-star Gil Hodges and former Rookies of the Year Jim Gilliam and Don Newcombe. The Yankees won the first two games, but Brooklyn took Game Three. Larsen started Game Four for the Yankees and did not fare well. Although staked to a 3-1 lead, he gave up a leadoff home run to Campanella in the fourth inning. Larsen then walked Carl Furillo, and Hodges hit a two-run homer to put the Dodgers ahead. In the fifth inning Gilliam led off with a walk and stole second while Reese was batting, At this point Stengel replaced Larsen with Johnny Kucks, who gave up a single to Reese and a three-run homer to Snider, one run of which was charged to Larsen. When Yankees were unable to catch up, Larsen was tagged as the losing pitcher, with a line for the game of five earned runs on five hits and two walks.

Brooklyn won Game Five to go ahead in the Series, three games to two. New York evened it up by taking Game Six. The Series came down to Game Seven. Johnny Podres pitched a masterpiece, shutting out the Yankees, 2-0, thereby earning Brooklyn its first-ever world championship.

Larsen was thrilled to have pitched in the Series: “I had stretched beyond my childhood dreams by playing for the Yankees in the World Series. Even though we lost the championship to the Dodgers, I was thankful to have been even been there in the first place.”11

Larsen’s appetite for strong drink and exuberant night life did not diminish. Mickey Mantle said of him, “Don had a startling capacity for liquor. Larsen was easily the greatest drinker I’ve known and I’ve known some pretty good ones in my time.12 During spring training 1956 Larsen wrecked his brand-new Oldsmobile by driving it into a St. Petersburg telephone pole at 4 or 5 o’clock one morning. He admitted that he had been drinking at several bars earlier in the night and said he had fallen asleep at the wheel.

His teammates thought Larsen was a bachelor, a devil-may-care playboy.13 They were shocked to learn of his secret marriage. Although Don and Vivian did not live together, she had moved to New York, attempting to collect some child-support money. On July 16, 1956, Justice Henry Greenberg of the Bronx Superior Court awarded Vivian $60 a week from Don in support of herself and their daughter, Caroline Jean.14 Don didn’t deliver. Living the high life that he enjoyed can be very expensive in New York City. He was having trouble making ends meet.15 He certainly didn’t have any spare cash to spend on a wife or child. He even asked the Yankees’ traveling secretary, Bill McCorry, for an advance on his World Series share: “I’ve got to get home to California when this is over, and I don’t have a nickel.”16 McCorry promised to deliver the cash if the Yankees won.

In October Vivian filed a complaint over Larsen’s failure to pay child support. (He had made four payments, then stopped paying.) He owed $420, for seven weeks in arrears at $60 per week.) Vivian’s lawyer, Harry Lipsig, said, “While this baseball hero is enjoying the luxuries of life and the plaudits of the public, he is subjecting his 14-month-old baby girl and his wife to the pleasures of a starvation existence.”17 Bronx Superior Court Justice Sam H. Hofstadter filed an order requiring the Yankees, Larsen, and baseball Commissioner Ford Frick to show cause why his World Series share should not be seized by the Bronx Supreme Court.18

The court order was in Larsen’s locker when he took the mound in Yankee Stadium and pitched the most incredible game in World Series history. The Yankees had won the pennant for the second straight year in a streak that was to yield four consecutive flags. They faced the defending World Series champion Brooklyn Dodgers.

The Dodgers won Game One at Ebbets Field behind the pitching of Sal Maglie. Larsen pitched briefly in Game Two. He faced only 10 batters, six of whom reached base safely, one on a base hit, one on an error, and four by means of walks. Larsen was charged with four unearned runs. The Dodgers won a slugfest. The Series then moved to Yankee Stadium. The home team won Games Three and Four to even the Series at two games apiece. Given Larsen’s poor performances in the 1955 fall classic and Game Two of the present match, there was little reason to expect him to start another game in the Series.

On the night before Game Five, Larsen went out for a few beers with Arthur Richman, a sportswriter for the New York Daily Mirror. Before midnight they headed back toward Larsen’s hotel apartment. During the cab ride Larsen told Richman, “I’m gonna beat those guys tomorrow. And I’m just liable to pitch a no-hitter.”19 It was typical Larsen bluster. Actually, he had no idea he was going to pitch. Stengel had not yet announced the starting pitcher for the next day’s game. Following the Yankees custom at the time, whenever the starter had not been determined the night before, in the morning coach Frankie Crosetti would place the warm-up ball for the day’s game in one of the starting pitcher’s shoes.20

Earlier that evening Herman Carey, father of Yankees third baseman Andy Carey, entered a novelty shop on Times Square that printed fake newspaper headlines. He purchased two. One read “Larsen Pitches No-hitter.” The other stated “Gooney Birds Pick Larsen to Win Fifth Game.” He returned to the hotel and taped the one about the no-hitter to the door of Larsen’s room. Then he had second thoughts. He didn’t want to risk jinxing the pitcher. So he shredded the paper and disposed of it. He kept the other one, without showing it to Larsen at the time.

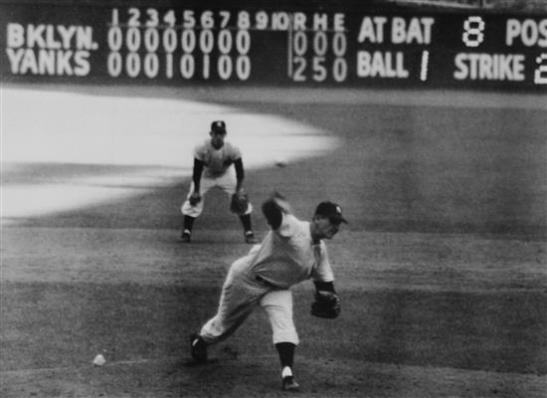

It turned out that the fake headlines were prescient. To the surprise of most of the Yankees, manager Stengel chose Larsen to start Game Five. The pitcher arrived at the ballpark early in the morning of October 8, saw the ball, and learned he would be the starting pitcher.21 He took a whirlpool bath and a cold shower, and had a rubdown.22 He lay down for a short nap in the clubhouse.23 Larsen was opposed by the tough Sal “The Barber” Maglie. Both men were at the top of their games. Using his new no-windup delivery, Larsen was unhittable. Maglie was almost as good, retiring the first 11 batters in a row until Mantle hit a solo blast in the fourth inning. By the end of the sixth inning it began to dawn on viewers that they might be watching history in the making. In keeping with baseball superstition, nobody on the Yankee bench mentioned a possible no-hitter, but surely it was on everybody’s mind.

It turned out that the fake headlines were prescient. To the surprise of most of the Yankees, manager Stengel chose Larsen to start Game Five. The pitcher arrived at the ballpark early in the morning of October 8, saw the ball, and learned he would be the starting pitcher.21 He took a whirlpool bath and a cold shower, and had a rubdown.22 He lay down for a short nap in the clubhouse.23 Larsen was opposed by the tough Sal “The Barber” Maglie. Both men were at the top of their games. Using his new no-windup delivery, Larsen was unhittable. Maglie was almost as good, retiring the first 11 batters in a row until Mantle hit a solo blast in the fourth inning. By the end of the sixth inning it began to dawn on viewers that they might be watching history in the making. In keeping with baseball superstition, nobody on the Yankee bench mentioned a possible no-hitter, but surely it was on everybody’s mind.

Larsen said he knew he was pitching a no-hitter, since every pitcher knows when he is throwing one. He said, “I tried to engage in conversation with some of our players on the bench during the game, but they all avoided me like the plague.24

Larsen mowed the Dodgers down, through the seventh, eighth, and into the ninth inning. He retired the first two batters in the ninth. Up came Dale Mitchell to pinch-hit for Maglie. Larsen’s first pitch was a ball, high and outside. Next came a slow curve over the plate for a called strike. Mitchell swung at another curve and missed for strike two. He fouled off a fastball. Then he took a quarter-swing at a fastball that seemed to some to be eye-high.25 Umpire Babe Pinelli called him out. Don Larsen had pitched the first no-hitter in World Series history. Not only was it a no-hitter, but it was a perfect game — no hits, no runs, with no one reaching base.

“Damn,” said sports reporter Dick Young. “The imperfect man just pitched a perfect game.”26

Shirley Povich of the Washington Post wrote, “The million-to-one shot came in. Hell froze over. A month of Sundays hit the calendar. Don Larsen today pitched a no-hit, no-run, no-man-reach-first game in a World Series.”27

The San Francisco Chronicle wrote about “madcap Don Larsen, a carefree soul who breaks automobiles, likes bright lights, reads comic books…and is just about the last person in baseball who might be expected to pitch a perfect game.”28

Larsen sent $420 to Harry Lipsig to give to his wife and daughter. “This man is still no hero,” the lawyer said. “In these proceedings, he has brazenly suggested when his daughter was born she was immediately to be given out for adoption.”29

The Dodgers won Game Six, but the Yankees took Game Seven and again reigned as baseball’s world champions.

One month after Larsen’s perfect game, he and Vivian divorced.

In 1957 Larsen got off to a poor start, but improved toward the end of the season, winding up with a commendable 10-4 record. The Yankees won the pennant again. In the World Series against the Milwaukee Braves, Larsen won one and lost one. In Game Three he relieved Bob Turley in the second inning and pitched well throughout the game, getting credit for the win as the Yankees prevailed, 12-3. In Game Seven Larsen was the starting pitcher, but was knocked out of the box in the third inning. With one out and a man on base, shortstop Tony Kubek made an errant throw to second base on a grounder hit by Johnny Logan. Eddie Mathews then doubled, and Larsen was out of the game. Lew Burdette pitched a shutout for his third win of the Series. The Braves were world champions for the first time since the Miracle Braves of 1914.

On December 7, 1957, Larsen married Corrine Bruess, a 26-year-old flight attendant from Minnesota, whom he had met on a flight out of Kansas City. This marriage endured. Apparently Corinne brought some much-needed stability to his life. The union produced one son, Scott, born October 5, 1962.

Both New York and Milwaukee repeated as pennant winners in 1958. Larsen started two games in the 1958 World Series. In Game Three he pitched shutout ball until relieved by Ryne Duren in the eighth inning and received credit for the win in the Yankees’ 4-0 victory. In Game Seven Larsen was removed in the third inning with one out and two Braves on base and the Yankees leading, 2-1. Bob Turley erased the Braves threat and was credited with the win as the Yankees won the game, 6-2, for their 18th triumph in the fall classic.

The Yankees slipped to third place in the 1959 standings and Larsen had a losing record at 6-7. On December 11, 1959, he was traded, along with Hank Bauer, Norm Siebern, and Marv Throneberry, to the Kansas City Athletics for Joe DeMaestri, Roger Maris, Kent Hadley, and Gerry Staley.

Larsen had very little success in Kansas City, losing 10 out of 11 decisions. The A’s sent him down to Dallas-Fort Worth in the Triple-A American Association, where he won two of three decisions, earning another shot at the majors. He appeared in only eight games for the A’s before being traded with Andy Carey, Ray Herbert, and Al Pilarcik to the Chicago White Sox for Wes Covington, Stan Johnson, Bob Shaw, and Gerry Staley. He had a combined 8-2 record for the two clubs.

Soon he was on the move again. On November 30, 1961, Larsen was traded with Billy Pierce to the San Francisco Giants for Bob Farley, Eddie Fisher, Dom Zanni, and Verle Tiefenthaler. In the City by the Bay, Larsen became a full-time reliever, winning five games and saving 10. The Giants finished the regular season tied for first place with the Los Angeles Dodgers. In the deciding game of the three-game playoff for the pennant, Larsen relieved Juan Marichal in the eighth inning and received credit for the win, as the Giants won their first championship after their move to the West Coast. In Game Four of the 1962 World Series against the New York Yankees, Larsen picked up a win, even though he pitched only one-third of an inning. He entered the game in the bottom of the sixth inning, with two outs, runners on first and second, and the game tied, 2-2. Larsen walked Yogi Berra to load the bases and then induced Tony Kubek to ground out, ending the inning. In the top of the seventh, Larsen was lifted for a pinch-hitter, as the Giants took a lead they did not relinquish.

In 1963 Larsen had a 7-7 record with four saves for the Giants. The much-traveled pitcher was sold to the Houston Colt .45’s on May 20, 1964, and was traded less than a year later to the Baltimore Orioles for Bob Saverine and cash. He won only one game for the Orioles before being released on April 11, 1966. He spent much of the next three seasons in the minors, toiling for clubs in Phoenix, Dallas-Fort Worth, Tacoma, and San Antonio.

Before the 1967 season began, the Chicago Cubs signed Larsen as a free agent. He pitched only four innings for the Cubs. His final major-league appearance came on July 7, 1967, at Houston’s Astrodome in an 11-5 Cubs loss. He entered the game in the sixth inning and pitched two innings, giving up one run and one base on balls. On the last pitch the 37-year-old Larsen threw in the major leagues, Jim Wynn flied out to Billy Williams in left field to end the seventh inning. Larsen was removed for a pinch-hitter in the eighth inning, and his major-league career was over.

After retiring from baseball, Larsen worked for about 25 years as a salesman for the Blake, Moffett & Towne Paper Company in the San Jose area. When he retired from this occupation, he, Corinne, and Scott moved to the shores of Hayden Lake, not far from Coeur d’Alene in Idaho’s scenic Panhandle, about 100 miles from the Canadian border. “I like Idaho because it’s peaceful and quiet,” Larsen said.30

Don’s son, Scott, as of 2015 was a maintenance technician for an aerospace company in Idaho. Scott and his wife, Nancy, gave Don two grandsons, Justin and Cody. Don, his sons, and grandsons enjoyed trout fishing and frogging together, hunting by spotlights in the cool of a northern Idaho morning.31

In 2012 Larsen announced that he was retrieving the uniform he had worn when pitching the perfect game. He had loaned it to the San Diego Hall of Champions, but he intended to auction off his most prized possession to raise money for his grandchildren’s college educations. He listed it with Steiner Sports Marketing for an online auction that ran from October 8 to December 2 at steinersports.com. “I really don’t know what it’s worth,” Larsen said. “But what I do know is that in terms of historic importance, my uniform is a part of one of the greatest moments in the history of sports. I have thought about that perfect game, more than once a day, every day of my life since the day I threw it.”32

The auction attracted 22 bids. The uniform sold for $756,000. The winning bidder was Pete Seigel, CEO of Gotta Have It, a New York City gallery that collected and displayed pop-culture memorabilia. Seigel said that Larsen’s uniform would be a welcome addition to a collection of Yankees memorabilia that his company was building.33

Three-quarters of a million dollars is surely enough to pay Justin and Cody’s college expenses. There may be enough extra cash to enable the Larsen family to take their hoped-for trip to Alaska.

Postscript

Don Larsen died at the age of 90 on January 1, 2020, in Hayden, Idaho.

An earlier version of this biography appeared in SABR’s “No-Hitters” (2017), edited by Bill Nowlin. It also appeared in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Notes

1 Don Larsen and Mark Shaw, The Perfect Yankee: The Incredible Story of the Greatest Miracle in Baseball History (Champaign, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing, 1996), 37.

2 Lew Paper, Perfect: Don Larsen’s Miraculous World Series Game and The Men Who Made It Happen (New York: New American Library, 2009), 12.

3 Paper, 13.

4 Larsen and Snow, 77.

5 Larsen and Snow, 1.

6 Peter Golenbock, Dynasty: The New York Yankees1949-1964 (Mineola, New York: Dover Publishing, 201), 292.

7 Paper, 13.

8 Paper, 14.

9 Paper, 17.

10 Paper, 14.

11 Paper, 15.

12 Paper, 16.

13 Paper, 17

14 Ron Rembert. “Baseball Immortals: Character and Performance On and Off the Field,” in Peter Carino, ed., Baseball/Literature/Culture Essays (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2004), 139.

15 Roger Kahn. The Era, 1948-1957, When the Yankees, the Giants, and the Dodgers Ruled the World (New York: Ticknor and Fields, 1993), 331.

16 Paper, 17.

17 Ibid.

18 Rembert.

19 Paper, 5.

20 Don Larsen, “The Game I’ll Never Forget.” Baseball Digest, October 2003: 54.

21 Ibid.

22 Kahn, 332.

23 Paper, 6.

24 Larsen, op. cit., 55-56.

25 Kahn, 332.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

28 Larsen and Shaw, 209.

29 Ibid.

30 Larsen, 56.

31 Newark Star-Ledger, October 9, 2012.

32 New York Times, May 26, 2012.

33 New York Daily News, December 6, 2012.

Full Name

Don James Larsen

Born

August 7, 1929 at Michigan City, IN (USA)

Died

January 1, 2020 at Coeur d'Alene, ID (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.