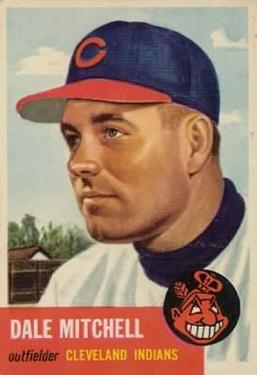

Dale Mitchell

The small town of Colony, Oklahoma, began as an agricultural settlement for Native Americans trying to adapt to a new way of life. In 1886 about 120 Cheyenne and Arapahos left their tribal lands in an attempt to assimilate themselves into the American culture. They became farmers, growing such staples as wheat and cotton. Six years after Colony was established, the land became open to settlers other than Indians. Several thousand people gathered in Washita County, settling in towns including Burns Flat, Corn, and Dill City. Early in the 20th century John H. Mitchell and his wife, Mary, rode their ancient covered wagon to become tenant farmers in Colony. The population at that time stood at around 200 to 250, most of them small farmers trying to scratch out a living through honest labor. Try as they might, many of the farmers were dirt-poor, the Mitchells among them. The town had a bank, a blacksmith shop, a newspaper and a small hotel for the few travelers looking for a place to stay the night.

The small town of Colony, Oklahoma, began as an agricultural settlement for Native Americans trying to adapt to a new way of life. In 1886 about 120 Cheyenne and Arapahos left their tribal lands in an attempt to assimilate themselves into the American culture. They became farmers, growing such staples as wheat and cotton. Six years after Colony was established, the land became open to settlers other than Indians. Several thousand people gathered in Washita County, settling in towns including Burns Flat, Corn, and Dill City. Early in the 20th century John H. Mitchell and his wife, Mary, rode their ancient covered wagon to become tenant farmers in Colony. The population at that time stood at around 200 to 250, most of them small farmers trying to scratch out a living through honest labor. Try as they might, many of the farmers were dirt-poor, the Mitchells among them. The town had a bank, a blacksmith shop, a newspaper and a small hotel for the few travelers looking for a place to stay the night.

On August 23, 1921, the Mitchells celebrated the birth of a second son, Loren Dale. Their first child, Billy, had been born in 1906. The sparsely populated community had few children Dale’s age to toss a football or baseball with. John Mitchell bought a first baseman’s glove for his left-handed son to practice with. At times some of the nearby farmers would stop by the Mitchell farm and hit fly balls which the eager young man chased across the wide-open land. Dale attended a two-room elementary school that had only about 30 students. There were no amateur teams to catch on with: There were not enough boys to cover the infield and outfield.

At the age of 10 Dale walked two miles to get to school. Occasionally he hitched a ride when he could flag down a traveling cotton wagon. One day after school he was riding a wagon back to the Mitchell farm. The horse-drawn wagon stopped at the side of the road and Dale hopped off to walk the short distance home. He started to cross the road just as an automobile attempted to pass the stationary wagon. At that exact second a huge water truck came bearing down the highway directly at the auto. The driver of the car swerved sharply to his right to avoid the truck, but had no time to stop, and hit the 10-year-old square on. Dale flew through the air and landed on the road unconscious. The three men at the scene rushed the young boy to a local hospital, where x-rays showed a broken left collarbone along with cuts and gashes on his face. Dale missed two months of school recovering from his injuries, but healed well, returning to his daily regimen of basketball. He had much more speed and size than any of his classmates, and could get to the basket with relative ease.

As a teenager Dale enrolled in Cloud Chief High School, which had a district covering 40 square miles. Despite the giant region to draw from, Cloud Chief had only about 160 students. But there were enough for a young athlete to compete at baseball, basketball, and track. Before he graduated, the “Cloud Chief Clouter” earned 12 athletic letters. He was all-state in basketball, and set setting a state record in the 100-yard dash with a time of 9.8 seconds – not quite up to par with Jesse Owens but a tremendous feat nonetheless. Knowledge of Mitchell’s athletic accomplishments became widespread, which led to a visit from a professional baseball scout.

Hugh Alexander, a former outfielder for the Cleveland Indians, was the scout. Besides the standard contract, Alexander verbally offered the family monthly payments until their underage son graduated from high school and reported to his minor-league assignment. With a handshake agreement the Mitchells put their signatures on the contract. All was well until about a month later, when the payments failed to arrive. Alexander claimed that somebody in the Cleveland front office decided to ignore the agreement as it was not specified in the contract. Angry with the turn of events, Dale refused to check in with Fargo-Morehead of the Northern League, where the Indians had placed him. Despite numerous phone calls, telegrams, and letters from the Indians organization, he declined to report unless the monthly payments arrived. He could not say anything publicly for fear of losing his amateur status for the remaining track season and the possibility of playing college sports. Years later Mitchell said the family had signed the contract because of his father’s poor health. They needed money immediately to help pay the medical expenses. All parties were willing to break the rules to help the elder Mitchell and let Dale continue with high-school sports. However, the Indians’ refusal to honor Alexander’s offer created another problem. Like it or not, Dale was Cleveland’s property, which meant he could not negotiate with any other professional team. So began a secret holdout that lasted an unheard-of seven years.

After graduation, Mitchell married his best girl, Margaret Emerson, a classmate at Cloud Chief. The newlyweds left Washita County to live in Norman, Oklahoma, a more convenient location for their future plans.

Since few people knew about the signed contract, Mitchell went ahead and enrolled at the University of Oklahoma. As a freshman in 1940 he was ineligible to play varsity sports, but the following summer he played semipro baseball with the Oklahoma Natural Gas club. Mitchell flourished there under the guidance of coach Roy Deal. Later he said, “I had a habit of stepping away at the plate and pulling the bat with my body. … Deal taught me how to spread my stance and hit with my wrists. This enabled me to hit outside balls and thus bat better against southpaw pitching.”[fn]Dale Mitchell file, Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York.[/fn]

With an improved hitting stance, Mitchell had an excellent season as a sophomore for the Sooners, batting .420. He no longer played basketball, but still ran track. He seemed to be on the way to challenge the record books, but World War II was on, and the 21-year-old was drafted and eventually sent to Europe for three years as a member of the Army Air Force. Serving as a quartermaster, Mitchell spent most of the war in England and France, remaining there until Germany surrendered in 1945. His son Dale Jr., who was 2½ years old at the time, remembered his dad arriving home, getting out of a car in full uniform with a duffle bag over his shoulder. It was the first time father and son had seen each other.[fn]Author interview with Dale Mitchell, Jr., December 2010.[/fn]

After his discharge from the Army, Mitchell returned to college, where he played baseball once again. He had a spectacular season, batting a remarkable .507. At this point some much-needed good fortune came into play. The Cleveland organization entered into a working agreement with Oklahoma City of the Double-A Texas League. Needing some money to support a wife and young son, Mitchell took a deep breath, then approached the owners of the club about playing ball for them. He revealed the details about the 1939 contract fiasco along with his desire to end the marathon stalemate with the Indians. The owners were sympathetic to the plight of the ex-serviceman. They contacted the home office in Cleveland, asking the executives to assign Dale to Oklahoma City. Much to everyone’s relief the request was granted, ending the seven-year holdout.

On June 3, 1946, Mitchell made his first appearance as a minor-league ballplayer. He likely had a case of nerves, going hitless in four at-bats with two strikeouts. He recovered quickly, spraying base hits all around the Texas League and winning the batting championship with an average of .337. The Indians called him up in September. To help things go smoothly, the Oklahoma City owners accompanied their best player to Cleveland. They met with Indians owner Bill Veeck to explain the unusual circumstances that had kept Mitchell away from professional baseball for seven years. As Mitchell later said, “Veeck made amends.” Veeck told Hal Lebovitz of the Cleveland News, “I couldn’t let the world’s record for determination go unrewarded!”[fn]Mitchell file.[/fn]

Pleased with the Cleveland owner’s generosity, Mitchell made his major-league debut on September 15, 1946, at Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium . Batting second and playing center field, he lashed out three singles in five at-bats, helping the Indians to an 8-1 victory over the Philadelphia Athletics. Mitchell played the final 11 games of the season, batting like a Hall of Famer. His average for the very short trial was an eye-opening .432. However, his fine hitting went virtually unnoticed. The only excitement left for the sixth-place Cleveland team was Bob Feller’s attempt to break the American League strikeout record, held at the time by Rube Waddell.

In 1947 Mitchell reported to spring training at Tucson, Arizona, a candidate for the center-field job. He had the necessary speed, but lacked the throwing arm and experience to claim the job. Tris Speaker, who was on the coaching staff, worked with the outfielders, and one could not hope for a better teacher than Speaker, who was one of the best center fielders in baseball history. Speaker paid great attention to his student, teaching Mitchell the correct way to break for line drives and flies. Mitchell spent much time learning how to get leverage in his throwing arm along with the proper way to field base hits. Reflecting on his time spent with the rookie outfielder, Speaker commented, “He was a grand pupil. I don’t see how he can miss.”[fn]Mitchell file.[/fn]

The 1947 season opened with Mitchell in the starting lineup. A slow start by the team and its new outfielder resulted in a benching, then a demotion back to Oklahoma City. Mitchell did not handle the setback very well, sitting at home waiting for the Indians to call him back. He did not play a single game for the minor-league club. There he remained until June 2, when the Indians decided to bring him back for another look. An article in Baseball Digest later stated that Cleveland had violated a rule by sending a war veteran back to the minors. The article mentioned that several teams put in a claim for Mitchell, forcing Veeck and manager Lou Boudreau to make a quick decision.[fn]Mitchell file.[/fn]

With two outfielders injured, Mitchell returned to the lineup, this time in left field. He hit the ball everywhere: line drives to left center, bouncing balls over the pitcher’s mound, and singles between third base and shortstop. When he did not connect solidly, his great speed allowed him to beat out infield hits at a regular pace. He ran off a 22-game hitting streak. Though not regarded as a power hitter, Mitchell surprised fans and teammates by one day launching a mammoth home run into the right-field grandstand at Municipal Stadium. He was reportedly only the fourth batter to accomplish the feat since the ballpark opened in the early 1930s.

Mitchell batted .316 in 123 games. In 493 at-bats he struck out only 14 times, an average of once every 35 trips to home plate. Speaker marveled at his student’s ability to make contact, telling reporters, “The man has one of the best batting eyes in baseball.”[fn]Mitchell file.[/fn] With great bat control, Mitchell would frustrate American League pitchers for years to come.

In 1948 spring training Mitchell worked hard in left field, chasing fungoes off Speaker’s bat. He would race to the outfield fence to grab high fly balls, then sprint toward the infield to snag line drives off his shoetops. The extra fielding sessions helped him become a reliable fielder. Mitchell’s hitting did not need much fine tuning; he continued to drive the baseball to all parts of the ballpark. Teams would try to load up the third-base side of the field against him, often moving the shortstop close to the hole, while the left fielder would stand a few steps away from the left-field foul line. This strategy had little success during the regular season. Mitchell concentrated on driving the ball to left-center or straightaway center, frustrating the defense. He told reporters, “I have learned to relax at the plate. When I feel I am getting tight I step out of the box and drop my bat. This has helped to get more power. I fool ’em now and get more punch in my swing.”[fn]Mitchell file.[/fn]Though he would never be known as a home-run hitter, Mitchell began to hit for extra bases, collecting a fair number of doubles and triples. In the pennant-winning season of 1948 he finished with 30 doubles and eight triples among his 204 base hits, second in the American League. His batting average of .336 left him in third place, behind only future Hall of Famers Ted Williams and teammate/manager Lou Boudreau. In 608 at-bats he struck out only 17 times. As a leadoff hitter Mitchell fit perfectly in the batting order, getting on base for the likes of Joe Gordon, Larry Doby, and Boudreau. But one of his best moments during the season occurred not at bat, but in left field. Playing at Detroit on June 30, Mitchell watched as fellow Indian Bob Lemon worked on a no-hit bid. In the seventh inning the Tigers’ third baseman, George Kell, sent a drive to deep left field. Like the track star he was, Mitchell raced back to the fence, speared the ball, and crashed into the wall. He hit the ground hard but held the baseball, preserving Lemon’s no-hitter.

A World Series win by the Indians over the Boston Braves in 1948 paid a winner’s share of $7,000. Rather than throw the money around in celebration, Mitchell purchased farmland near his residence in Oklahoma. He bought 160 acres, which he leased to wheat farmers. He did this again with Series money in 1954 and 1956. He controlled the 480 acres the rest of his life, giving his family security after his playing days were over.

Though there would be no more postseason play for the Indians for six seasons after 1948, Mitchell continued to hit over .300 while playing a very good left field. In 1949 he swatted an amazing 23 triples, best by a wide margin in the major leagues, putting him three behind Joe Jackson and Sam Crawford for the highest total ever recorded in the American League. His 203 hits were tops in the junior circuit, nine ahead of runner- up Ted Williams. At this point Dale was collecting a salary of $18,500, a huge improvement over his rookie pay of $7, 000. Before he retired, his salary peaked at a very respectable $32,000.

Sportswriters sometimes asked Margaret Mitchell what was so unusual about her husband, if anything. Once she replied, “In the ten years we have been married, Dale has been what you might call a good, solid citizen. I have been waiting for something to happen [said with a smile]. That’s what keeps me interested.”[fn]Mitchell file.[/fn] For his part Mitchell kept himself amused by playing golf and a mean gin rummy with Akron Beacon Journal reporter Jim Schlemmer. Asked by Schlemmer, the Indians beat reporter, to speak at a sports banquet, Mitchell agreed, saying he couldn’t refuse because he already had too much of Schlemmer’s money.

Early in the 1952 season Mitchell found himself on the bench, replaced by a hot prospect named Jim Fridley. Manager Al Lopez thought he could generate more runs in the lineup with younger players like Fridley and Harry Simpson to go along with stalwarts Larry Doby and Luke Easter. Injuries to the latter two pushed the 31-year-old Mitchell back in the lineup. He responded by going off on a rampage, hitting .382 during of May. For the season he finished with an average of .323, his best in four years.

Life was pretty good for the Mitchells. Unlike his father, who had struggled mightily to scrape out a living, Mitchell had done well in his baseball career. He had many good friends in the game, including Bob Kennedy, Bob Lemon, and Hal Naragon. He could now enjoy the fruits of his labor, renting roomy houses in Cleveland during the baseball season, then returning to Oklahoma for the winter. Son Dale Jr. recalled moving to northeast Ohio each April and finishing his school term there. Once summer vacation began, young Dale went to the ballpark every day with his father. He had his own Indians uniform and shagged fly balls with Mike Hegan and other players’ sons. At times the coaches would throw batting practice to the boys before their dads took the field. Each summer Dale Jr. went on a road trip, usually to Detroit or Chicago. The only rule he had to obey was to keep away from Early Wynn and Bob Feller, who did not enjoy having children on the field while they practiced. Other than the one restriction, summers were a grand time for father and son.

The 1953 season was the last in which Mitchell, by then 31 years old, appeared in the everyday lineup. He responded with an average of .300 and a career best in home runs, 13. He spent his final three years with the Indians as a pinch-hitter, getting no more than 50 or 60 at- bats in each season. He made two plate appearances in the disappointing 1954 World Series, failing to get a base hit.

The 1956 season showed the 34-year-old left fielder at the end of his career, hitting an all-time low.133. At the end of July 1956, the Brooklyn Dodgers claimed Mitchell for the waiver price of $10,000 plus a player to be named later. A week earlier the Dodgers and Indians had played an exhibition game in which Mitchell banged out a triple and a single. Brooklyn sorely needed a reliable pinch-hitter. In his first at-bat with his new club, Mitchell proved he still had some pop in his bat, delivering a single in the eighth inning to score Jackie Robinson with the winning run against Milwaukee. The Dodgers won the National League pennant and advanced to the World Series against the New York Yankees. In Game Five, Don Larsen was pitching a perfect game when Mitchell was sent up as a pinch-hitter with two outs in the ninth inning. With the tension mounting, Mitchell took a ball, then a strike. He recalled years later, “I got a pitch to hit from Larsen. I think it was the second pitch, a hanging curve that I fouled off. If you miss your pitch you’re out of business.”[fn]Mitchell file.[/fn] Larsen delivered one more time, a pitch off the outside corner. Umpire Babe Pinelli called it a strike, which gave the Yankee pitcher his perfect game. Mitchell turned to argue with the umpire, but Pinelli had already left. Doubters have insisted that the called third strike was nowhere near the plate. For the rest of his life Mitchell insisted that the pitch was a ball. When you have nearly 4,000 at-bats during your career and you strike out a minuscule 119 times, you may have something there. In 1986, on the 30th anniversary of the perfect game, Good Morning America invited Mitchell to come on the show and talk about the game with Larsen and Yogi Berra. Mitchell refused to go on, saying he was not going to travel across the country to talk on TV about striking out. After 11 years in major-league baseball with a career average of .312 and two All-Star game appearances, he had earned the right.

Mitchell had one more at-bat in Organized Baseball, a pinch-hitting appearance in Game Seven of the ’56 Series. He retired after the season and began a new profession in the oil business. Later he joined the Martin Marietta Corporation as president of its cement division in Denver. He retired in the early 1980s. He played a lot of golf and took part in many old-timer’s games at Yankee Stadium. While visiting with old friends and former teammates, he became acutely aware of the number of former players who couldn’t pay hotel and transportation costs. He gave money to several who were destitute. He did this for a number of years until the sadness of seeing his old buddies in such a depressing state proved too much for him, and he no longer went to the old-timer’s games.

In October 1981, the University of Oklahoma unveiled its new baseball stadium, Dale Mitchell Field. An alumni game featured former Sooners and current major leaguers Mickey Hatcher, Bob Shirley, Jackson Todd, George Frazier, and Joe Simpson. Mitchell was honored in the dedication ceremony for his tireless efforts to raise money for the ballpark. Despite a stellar baseball career, Mitchell called this honor the biggest of his life. And why not? A great collegiate athlete and student himself, what could be better than his alma mater paying him a tribute that would last for a lifetime?

Dale Mitchell suffered a severe heart attack and died on January 5, 1987, in Tulsa, Oklahoma. He was 65 years old. In 1973 he had had a bout with heart trouble but recovered to spend another 14 years with his children and grandchildren. Mitchell had come a long way from a tenant farm in Colony, Oklahoma ,to become an elite baseball player and a top executive in the business world. Though he accomplished much in life, baseball was never far from his thoughts. As he told a reporter in 1974, “You never leave baseball once you’re in it. You always love the game.”[fn]Mitchell file.[/fn]

This biography is included in the book Pitching to the Pennant: The 1954 Cleveland Indians (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Joseph Wancho. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Sources

Dale Mitchell file, Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York

Cleveland Plain Dealer, 1946

Interview Dale Mitchell, Jr., December 2010

Society for American Baseball Research

Washita County Historical Society, Cordell, Oklahoma

Full Name

Loren Dale Mitchell

Born

August 23, 1921 at Colony, OK (US)

Died

January 5, 1987 at Tulsa, OK (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.