‘The Writers Are Bad’: Roberto Clemente and the Press

This article was written by Vince Guerrieri

This article was published in ¡Arriba! The Heroic Life of Roberto Clemente (2022)

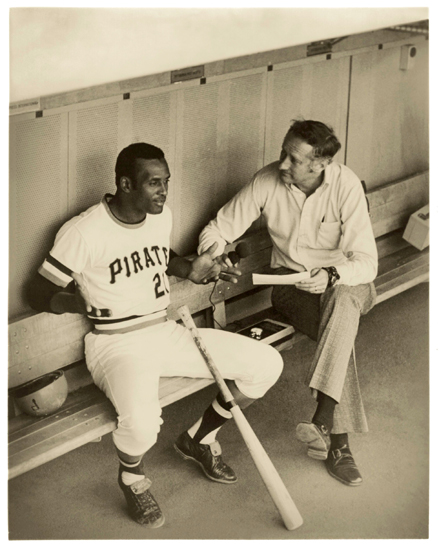

Roberto Clemente speaks with reporters. (Les Banos photograph courtesy of The Clemente Museum.)

In what turned out to be the last book of his illustrious career, Jimmy Breslin wrote a biography of Branch Rickey, focusing on his signing of Jackie Robinson and integration of baseball.

Breslin was himself a former sportswriter, most notably covering the New York Mets’ comically inept expansion season for the New York Journal-American, using it as fodder for a book, Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game?1 In the Rickey biography, Breslin noted how unwilling or unable baseball writers were to advocate for integration, just as hidebound as the owners who paid for their meals and travel. “The Baseball Writers Association of America organization was a fake and a fraud,” Breslin wrote. “A shill as white as the Klan.”2 He noted that the BBWAA controlled press-box access, restricting it to daily newspapers – which perhaps not coincidentally, excluded the Black press, most of which were weekly newspapers.

It was into this world that Rickey brought Jackie Robinson in 1947, and it wasn’t much changed eight years later – almost to the day – when Roberto Clemente made his major-league debut. In some ways, it might have been even worse. While Robinson was college-educated and one of the first African Americans to attend Officer Candidate School during World War II, Clemente was a native of Puerto Rico with no more than a high-school education. Spanish was his first language, and initially, when he started playing professional baseball, his only one.

And that contributed to a mutually antagonistic relationship between Clemente and the press. The writers were only too happy to document his struggles with English and the reputation he earned – unfairly – as a hypochondriac and malingerer. He in turn had no interest in building any kind of relationship with the people who refused to recognize his greatness. It was a relationship that had only started to warm at his untimely death.

“The fans are good to me,” Clemente said in an Associated Press article in spring training in 1969. “Only the writers are bad.”3

Clemente was initially signed by the Dodgers, and it’s easy to wonder what his relationship with the press would have been like had he played his career in Brooklyn and then Los Angeles. “If he were playing in New York they’d be comparing him to DiMaggio,” said his former manager Bobby Bragan. “I would say his greatness is limited only by the fact that he does not hit the long ball consistently, and by the fact that he is not playing in New York, or even Chicago or Los Angeles.”4

But the Pirates found Clemente and claimed him in the Rule 5 draft, and he ended up in Pittsburgh, which was a pro sports wasteland at the time. The Steelers were the laughingstock of the NFL and the Pirates hadn’t won a pennant since they were swept by the Murderers’ Row Yankees in 1927. The Pirates of that era could be summed up with Branch Rickey’s riposte to slugger Ralph Kiner during contract negotiations: “We finished in last place with you. We can finish in last place without you.”

At the time, Pittsburgh had three daily newspapers, the Scripps-Howard Press, the Blocks’ Post-Gazette, and the Hearst Sun-Telegraph, then in its death throes. Les Biederman, the beat reporter for the Press, quoted Clemente phonetically, using “ees” for “is” and “dese” and “dose.” (Biederman also wrote for The Sporting News, so Clemente’s struggles with the language were spread to a national audience.)

Clemente was presented as a complainer, a player with a variety of aches and pains. He famously once said in spring training, “My bad shoulder feels good, but my good shoulder feels bad.” Some writers saw the humor in this, noting that the worse Clemente felt, the better he performed. Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray called Clemente “baseball’s Oscar Levant,” referring to the musician, actor, and all-around personality (ironically, himself a Pittsburgh native) who would complain about his various ailments, saying Clemente “had to have one foot in the Mayo Clinic before he could make a shambles of National League pitching.”5

But some writers saw more detrimental characteristics beyond the weariness of Clemente’s well-worn complaints. “Clemente’s a hypochondriac,” said Jack Hernon, who covered him for the Post-Gazette. “Always was. He can’t hit in the clutch; it’s a proven statistic. He’s always making excuses for something.”6

When Dick Stockton arrived at KDKA on his way to a national broadcasting career, he said Clemente was not a team player, a charge the outfielder found particularly distasteful – and he spelled out why in a spring-training tirade. “Did any ballplayer come up to you and say that I am not a team player? Who say that? The writers, right? Well I tell you one thing, the more I stay away from writers the better I am. You know why? Because they are trying to create a bad image for me. You know what they have against me? Because I am black and Puerto Rican.” He bore a grudge against Stockton for the rest of his life, at one point saying, “He come in this clubhouse, I tell you, I kill him.”7

Even positive press could lead to hurt feelings. Myron Cope, a celebrated magazine writer in the 1960s before going on to be the radio voice of the Steelers, wrote a profile on Clemente for Sports Illustrated, “Aches, Pains and Batting Titles.” It was a largely complimentary piece, but Clemente didn’t speak to Cope for several years afterward.

(Courtesy of The Clemente Museum.)

But while Clemente had a standoffish relationship with many of the reporters who covered baseball, he warmed quickly to Bob Prince, the Pirates’ radio voice. Prince, known as “The Gunner,” was an unabashed homer, willing to cheer on anyone wearing a Pirates uniform. Early in Clemente’s career, a teammate, Lino Donoso, a well-traveled Cuban hurler whose brief major-league career coincided with Clemente’s first two years in Pittsburgh, had taken to calling him Arriba, a Spanish word that literally means “upstairs” but has been taken more figuratively to mean “lifting or uprising.” Prince saw fit to yell “Arriba!” when Clemente came to bat or made a great play.8

Prince was not just a broadcaster. He became a friend and trusted adviser to many Pirates players. One night in 1958, the Pirates were playing the Giants in what Prince called “a real beanball contest. It looked like we were going to have a terrible fight.” Giants pitcher Ruben Gomez took a little chin music, and Orlando Cepeda, then a rookie, came out of the dugout carrying a bat to fight for his idol. Willie Mays tackled him and threw him to the ground. Prince said on the air, “This is a young Latin American player who’s very excited and doesn’t realize what he’s doing. You must forgive him, because he didn’t mean to do this.” Apparently, Clemente heard about it, and the next day, he arranged a meeting with Prince and Cepeda, telling the Baby Bull in Spanish what Prince had said.9

Clemente himself relayed this story in 1971, at a dinner in Prince’s honor in Puerto Rico. Prince was celebrating his 25th anniversary in broadcasting, and Clemente invited him to Puerto Rico, where he described him as “one of the best friends I have in the world” – indeed, Prince might have been the only person who could refer to Clemente as Bobby and not be upbraided for it – and bestowed on him one of his prized possessions: The silver bat he was presented in 1961 for the first of his four batting titles. The bat had special meaning to Clemente, who was determined to prove that he was a most valuable player after finishing eighth – below three of his Pirates teammates10 – in MVP voting the year before. At the dinner, both Clemente and Prince were in tears.11

Clemente finally received his National League MVP Award in 1966, edging out runner-up Sandy Koufax, who had completed his final season in baseball. Koufax went 27-9 and won his second straight (and third overall) Cy Young Award as the Dodgers won the pennant. It was the second straight year Koufax finished second in MVP voting.12

Clemente got a total of 218 points, 10 more than Koufax. By the rules of the day, each first-place vote was worth 14 points, each second-place vote was worth 9, 8 for third, and so on. Clemente appeared on all 20 ballots – the only player to do so13 – but Koufax had received more first-place votes.14

Koufax himself was writing his own story, serialized in newspapers. He said Clemente “can hit any pitch any where at any time. He will hit pitchouts, he will hit brushback pitches. He will hit high, inside pitches deep to the opposite field, which would be ridiculous even if he didn’t do it with both feet off the ground.”15

After winning the World Series in 1960, The Pirates spent the rest of the decade spinning wheels, but a move from Forbes Field in the city’s Oakland neighborhood to a new all-purpose facility on the North Shore, Three Rivers Stadium, seemed to revitalize their fortunes. In 1970 the Pirates won the first of three straight National League Eastern Division titles but were swept by the Cincinnati Reds in the National League Championship Series. The following year, the Pirates beat the San Francisco Giants and advanced to the World Series. The Pirates won in seven games – and Clemente hit safely in each of them, having done the same in the only other World Series he’d played in, in 1960.

“I feel that I would be considered to be a much better athlete if I were not a black Latin,” he said during the 1971 World Series. “I play as good as anybody. Maybe I play as good as anybody who plays the game. But I am not loved.”16 His .414 average earned him World Series MVP – and the plaudits that he felt he didn’t get enough of in his career to that point. “After 17 major-league seasons, 37-year-old Roberto Clemente is now an overnight sensation,” wrote Jerry Izenberg.17

Clemente played for one more season, getting his 3,000th hit against the Mets. The Pirates lost a hard-fought NLCS to the Reds, and everyone went home for the offseason. Clemente died on a mission of mercy, on board a plane that crashed shortly after takeoff with supplies for Nicaraguan earthquake victims.

Even in death, Clemente was denied the recognition he thought he deserved. Joe Falls of the Detroit Free Press made it a point to write about how unhappy Clemente seemed to be – and how he lacked the charisma of Willie Mays (a comparison that always made Clemente bristle). “Remember the All-Star game of a year ago, how we all waited for the first appearance of Willie Mays in Tiger Stadium? I don’t remember what Clemente did that night or even if he played.”18 (Clemente replaced Mays in the lineup and hit a home run off Mickey Lolich.)

Upon Clemente’s death, an unprecedented special election was decreed by the Baseball Writers Association of America for the Baseball Hall of Fame.19 Some sportswriters had a problem with this.

Bob Broeg wrote, “To steamroller Roberto into the Hall of Fame is really a disservice to the proud person who liked to feel he was best in life, not in death.”20

Dick Young, who less than two years earlier had called Clemente “the best damn ballplayer in the World Series, maybe in the whole world,” abstained.21 He said Clemente’s immediate election – a straight up-or-down vote with Clemente the only name on the ballot – was basically … communist.

“Just take another look at the ballot,” inveighed Young. “It is straight from beyond the Iron Curtain. Any man who has the temerity to vote no, and sign his name, will hear a knock on his door one night, and never again will be seen. Joe Stalin won more elections that way.”22

Young suggested that the BBWAA could have waived the five-year waiting period and then put Clemente on the ballot with that year’s other candidates.23 Instead, Clemente was “railroaded in,” preying on rank sentimentality, which offered him a chance to tee off on hoary clichés. “Anybody who says the presence of Roberto Clemente can be felt in the Pirates clubhouse is guilty of sentimental rot,” Young wrote. “They do not think all the time of Roberto Clemente, these teammates of his. To do so would be unreal, and to suggest so is dishonest. It is three months now since Roberto died a hero’s death in the shark-infested water of the Caribbean, and the time has tempered grief.”24

Murray Chass of the New York Times – himself no stranger to Hall of Fame voting controversies – grew up in Pittsburgh’s Squirrel Hill neighborhood, watching Clemente while a student at Taylor Allderdice High School and the University of Pittsburgh, and even covered him as one of those “New York writers” Clemente scorned. Chass said the ballot gave him pause as well, before voting yes. “I was reluctant to vote yes on this ballot because I was concerned that it might set an undesirable precedent. After debating with myself, however, I finally marked the yes box. I realized that if I didn’t vote for Clemente then, I would never again have the opportunity.”25

Of course, he was right. A total of 424 ballots were distributed, with 318 yes votes being the required 75 percent threshold. Clemente got 393. Young’s abstention was one of two, and 29 writers voted against inducting Roberto Clemente into the Hall of Fame, most more concerned with process than with recognizing greatness.26

VINCE GUERRIERI saw his first major-league game at Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh. A native of Youngstown, Ohio, he spent his salad days as a young reporter for the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review and spent every day he could at the newly opened PNC Park. He’s an award-winning journalist and author in the Cleveland area, and secretary/treasurer of the Jack Graney SABR chapter there.

Notes

1 The title was taken from a statement made in frustration by manager Casey Stengel.

2 Jimmy Breslin, Branch Rickey (New York: Viking, 2011), 106.

3 “Clemente Hits Press for Poor Coverage,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Times Leader, March 31, 1969, 20.

4 Jim O’Brien, Maz and the ‘60 Bucs (Pittsburgh: Geyer Printing, 1993), 256.

5 Jim Murray, “Don’t Cry for Clemente, Baseball’s Oscar Levant,” Los Angeles Times, September 18, 1966.

6 Phil Musick, Who Was Roberto? (New York: Doubleday, 1974), 137. Musick noted that Hernon, who died of cancer at the age of 48 in 1966, and Clemente didn’t speak for the last year of Hernon’s life for reasons known only to them.

7 Musick, Who Was Roberto?, 129.

8 Bruce Markusen, Roberto Clemente: The Great One (New York: Sports Publishing, 2001), 66.

9 Kal Wagenheim, Clemente! (New York: Praeger Publishing, 1973), 71.

10 Don Hoak was runner-up, and Vern Law was sixth in voting.

11 Wagenheim, 228-29.

12 The 1965 NL MVP was Williie Mays.

13 Clemente received eight first-place votes, 10 second-place votes, and two third-place votes.

14 Koufax received nine first-place votes. Clemente got eight. The Braves’ Felipe Alou got two first-place votes, and Dick Allen of the Phillies got the remaining one.

15 Rafael Pont-Flores, “Puerto Rico Fans All Root for Roberto,” The Sporting News, November 26, 1966, 26.

16 Wells Twombly, “Super Hero,” San Francisco Examiner, January 3, 1973. Roberto Clemente File, Baseball Hall of Fame.

17 Quoted in O’Brien, Maz and the ‘60 Bucs, 256.

18 Joe Falls, “Clemente: Sad Ending for a Troubled Man,” Detroit Free Press, January 2, 1973. Roberto Clemente file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

19 The closest parallel is Lou Gehrig’s election to the Hall of Fame. His career ended April 30, 1939, at the age of 36, and Gehrig was voted into the Hall of Fame on December 7, 1939. But at that point, there was no official five-year period between a player’s retirement and his eligibility for induction.

20 Bob Broeg, “Instant Enshrinement Is a Disservice to Clemente,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 20, 1973: 2B.

21 Reprinted by Jim O’Brien, Remembering Roberto (Pittsburgh: Geyer Printing, 1994), 437.

22 Dick Young, “Wrong Way to Honor Clemente,” New York Daily News, March 14, 1973. Clipping in Roberto Clemente file, Baseball Hall of Fame.

23 That year, Warren Spahn was the only player elected by the BBWAA. He was in his first year of eligibility, as were future inductees Whitey Ford and Robin Roberts. Other eventual Hall members who fell short of election that year included Bob Lemon, Duke Snider, and former Pirates slugger Ralph Kiner.

24 Young, “Wrong Way to Honor Clemente.”

25 Jim O’Brien, Remembering Roberto, 432

26 “Clemente in Hall of Fame,” Cleveland Press, March 20, 1973, part of the Press archives at Cleveland State University.