The 1935 Chicago Cubs

This article was written by Gregory H. Wolf

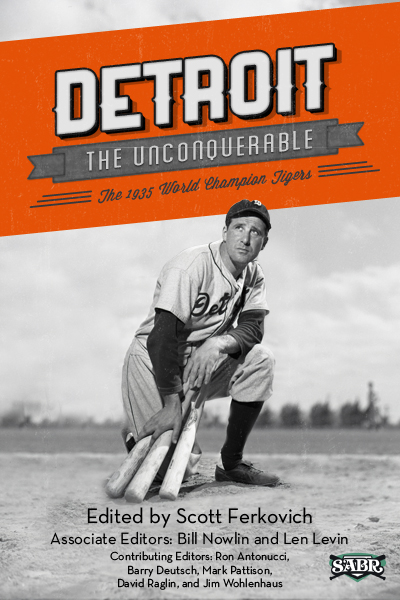

This article was published in 1935 Detroit Tigers essays

A look at the 1935 Detroit Tigers’ opponents in the World Series.

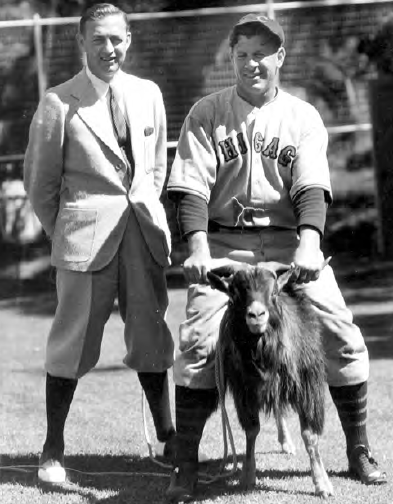

Cubs owner P.K. Wrigley and first baseman Charley Grimm pose in 1934 with … a goat. If only they had known. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY, COOPERSTOWN, N.Y.)

In 1935 the Chicago Cubs celebrated their 20th season playing in Wrigley Field (so named since 1927) by winning 21 consecutive pressure-packed games in September to capture an unlikely pennant in the last week of the season. The Cubs of this era were accustomed to good baseball. They had won the pennant in 1929 and 1932, and by the end of 1935 had strung together ten consecutive winning seasons (they collected another pennant in 1938 and extended their streak of winning seasons to 14 the following year). The losses in the 1929 and 1932 World Series, respectively to the Philadelphia Athletics and New York Yankees, were painful memories for fans, many of whom could still remember their team’s titles in 1907 and 1908; however, the 1935 team, with the best record in the big leagues (100-54), offered renewed hope.

The Context

The city of Chicago and the Cubs were vastly different in 1935 than they were in 1929. Just weeks after the Cubs’ loss in the World Series, the economic crash on Wall Street ushered in the Great Depression. Seemingly endless economic opportunity transformed into unimagined hardship, and by 1935 unemployment stood at over 20 percent nationally and even worse in Chicago. The famous mob wars of Al Capone and other gangsters of the 1920s and early 1930s had gradually dissipated even before the repeal of the Volstead Act (Prohibition) in 1933. William Wrigley, the Cubs’ innovative majority owner since 1921, died in January 1932. He was succeeded by his son, Philip K. Wrigley, a recluse and dispassionate baseball fan who, according to baseball historian Glenn Stout, lacked “creativity, self-confidence, initiative, vision, and other qualities often assigned to leadership.”1 The North Siders’ visionary general manager, Bill Veeck, Sr., who orchestrated the team’s rise to national prominence in the late 1920s, passed away in 1933. Veeck was replaced by Charles “Boots” Weber, but his footprint was still evident on the team. Stars from the 1929 club, like home-run-slugging Hack Wilson, arguably the NL’s biggest draw at the time, and ornery Rogers Hornsby, the league’s most feared hitter, seemed as though they were from a different era when the ball had more pop to it. Following the “Year of the Hitter” in 1930, the National League adopted a new ball with a thicker cover and raised stitching. Pitchers were able to grip the ball better; and the ball did not carry as well. Baseball had indeed changed.

Few sportswriters thought the Cubs had a chance to dethrone the reigning World Series champion St. Louis Cardinals in 1935. In a preseason poll, only 10 of 194 members of the Baseball Writers Association of America surveyed picked the Cubs to win the pennant; 126 of them chose the Cardinals.2 Cubs beat reporter Edward Burns spared no punches in his scathing evaluation of the team, coming off two consecutive third-place finishes. The Cubs are a “sluggish ball club, a team with an inadequate pitching staff, in addition to a lack of alertness,” he wrote as the team left its utopian spring-training camp on Catalina Island and traveled back east.3 The Cubs’ chances for a pennant, he argued, were nothing but a dream.

The Players

The Cubs fielded the NL’s youngest team in 1935, with productive veterans sprinkled in. Their unequivocal leader was 34-year-old catcher Gabby Hartnett. In his 14th season with the club, “Old Tomato Face” led the team with 91 runs batted in and a .344 batting average while donning the tools of ignorance in 110 games. He became the third Cubs player to win the NL Most Valuable Player Award, joining outfielder Frank Schulte in 1911 and Hornsby in 1929. Player-manager Charlie Grimm, affable skipper of the team since midseason of 1932, relinquished his ten-year hold on first base after the first two games of the season to 18-year-old Phil Cavarretta. In one of the most prolific seasons in big-league history for a teenager, Cavarretta batted. 275 in 589 at-bats and led the team with 12 triples. “The 1935 club, in all the years I worked with the Cubs, that was the best team I ever played on,” said “Phillabuck Phil,” who was with the Cubs through 1953. “That was the best infield I ever played with.”4

The Cubs fielded the NL’s youngest team in 1935, with productive veterans sprinkled in. Their unequivocal leader was 34-year-old catcher Gabby Hartnett. In his 14th season with the club, “Old Tomato Face” led the team with 91 runs batted in and a .344 batting average while donning the tools of ignorance in 110 games. He became the third Cubs player to win the NL Most Valuable Player Award, joining outfielder Frank Schulte in 1911 and Hornsby in 1929. Player-manager Charlie Grimm, affable skipper of the team since midseason of 1932, relinquished his ten-year hold on first base after the first two games of the season to 18-year-old Phil Cavarretta. In one of the most prolific seasons in big-league history for a teenager, Cavarretta batted. 275 in 589 at-bats and led the team with 12 triples. “The 1935 club, in all the years I worked with the Cubs, that was the best team I ever played on,” said “Phillabuck Phil,” who was with the Cubs through 1953. “That was the best infield I ever played with.”4

Twenty-five-year-old All-Star and future Hall of Famer Billy Herman anchored arguably the best infield in the National League. The fourth-year starter led the league with 227 hits and 57 doubles en route to 113 runs scored and a .341 batting average. He was supported by sure-handed 27-year-old Billy Jurges, also in his fourth year as a starter. Jurges, perhaps most noted for being shot twice by showgirl Violet Valli in July 1932, led NL shortstops in double plays (99). Stan Hack, 25, took over duties at third base on May 23, replacing offseason acquisition Freddie Lindstrom. “Smiling Stan” led all National League third sackers with a .311 batting average.

Considered to be its strength prior to the season, the Cubs’ outfield proved to be less consistent than anticipated. Twenty-three-year-old Augie Galan, a converted infielder who had never played the outfield before 1935, started all 154 games in left field. One of the surprise players of the year, Galan led the majors with 133 runs scored and batted .314 with 64 of his 203 hits going for extra bases. Kiki Cuyler, at age 36 and coming off an exceptional season in 1934 (.338 batting average) was slated for center field. He struggled (.268) and was ultimately placed on waivers, paving the way for 25-year-old Frank Demaree, who had belted 45 home runs and batted .383 the previous year with the Los Angeles Angels to earn the Most Valuable Player award for the Cubs’ affiliate in the Pacific Coast League. Former Philadelphia Phillies left-handed slugger Chuck Klein occupied right field for most of the season. Widely expected to be the team’s fearsome slugger when the Cubs acquired him before the 1934 season, the former Triple Crown winner failed to duplicate his success playing home games in the Baker Bowl, with its forgiving, 280-foot right-field wall (though his 21 home runs in 1935 led the Cubs). In the heat of the pennant race, Grimm shook up the outfield lineup on September 7 with just 20 games remaining, and the team trailing the Cardinals by 2½ games. He moved the hot-hitting Demaree (.319) from center field to right to replace the slumping Klein, and inserted veteran leader Lindstrom in center field. Lindstrom excelled after the switch, batting .337.

The Cubs’ biggest question mark going into the 1935 season was pitching. In the offseason they had broken up one of the big leagues’ most productive hurling trios, Guy Bush, Pat Malone, and Charlie Root, who had won a combined 336 games during their seven years together (1928-1934). Soon after the 1934 campaign, the Cubs sent Bush, Babe Herman, and Jim Weaver to the Pittsburgh Pirates for Lindstrom and left-hander Larry French. They also traded the disgruntled Malone to the Cardinals in exchange for catcher Ken O’Dea, who served as Hartnett’s principal understudy.

For the season, “Jolly Cholly” Grimm counted on six pitchers who combined to win 96 of the club’s 100 games while losing only 50, and logged 1,275 innings (91.4 percent of all innings). The staff ace was 26-year-old Lon Warneke (20-13), who won at least 20 games for the third time in four seasons. He was joined by second-year man Bill Lee, whom the Cubs had acquired from the Cardinals prior to the 1934 season in a rare mistake by Branch Rickey. Lee won 20 and lost just six to lead the NL with a .769 winning percentage. Rubber-armed French, coming off a disappointing 12-18 season with the Pirates, rebounded with a 17-10 record, tied Lee for the best ERA on the staff (2.96), and tied for the league lead with four shutouts. French was an overlooked dependable workhorse of the era, finishing with a 197-171 record and logging in excess of 3,100 innings in 14 seasons. While Warneke, Lee, and French got the bulk of the starts (92), Tex Carleton, Roy Henshaw, and Root picked up 58 of the other 62.

The Cubs acquired Carleton (11-8), a brooding right-hander, in the offseason from the St. Louis Cardinals, where he fought with teammates and resented the attention Dizzy and Paul Dean received. The 23-year-old Henshaw, who had spent the entire 1934 season with the Los Angeles Angels, was an invaluable spot starter and reliever and won a career-high 13 games. Arguably the biggest surprise of the season was 36-year-old Root, whom papers called the “grandpappy” of the staff.5 After appearing washed up, struggling with his weight, and winning just four times in 1934, Root started regularly in the second half of the 1935 season en route to a 15-8 record, and logged in excess of 200 innings for the ninth and final time in his 17-year big-league career.

“We won the pennant because of our complete team, especially our regulars … and our pitching staff,” said Cavarretta.6 The Cubs were indeed a complete team. Offensively, they led the circuit in runs scored, batting average, and on-base-percentage. Defensively, they recorded the most double plays in the league (163) and finished third in fielding percentage. The pitching staff led the NL in ERA (3.26) for the first time since their last World Series appearance, and also recorded the most complete games (81). Above all, the club was remarkably healthy.

The Season

The Cubs’ dramatic 1935 campaign can best be described as a tale of two seasons. The North Siders struggled to stay above .500 through July 5, when they lost their fourth consecutive game to fall to 38-32, a season-worst 10½ games behind the front-running New York Giants. Then they were a completely different team for the remainder of the season. Beginning on July 6, the Cubs went 62-22 to win the pennant by four games over the highly favored Cardinals. “Maybe the Cardinals had a better team,” said Cavarretta, “[but] we were young and we were hungry. We wanted to win more than the Cardinals.”7

On a cold day with temperatures on the 30s, Chicago Mayor Edward Joseph Kelly threw out the ceremonial first pitch at Wrigley Field to inaugurate Opening Day on April 16. The game served as a microcosm for the Cubs’ season: good pitching, timely hitting, and a little luck. In perhaps an omen for the Cubs, they knocked out the Cardinals’ reigning 30-game winner and World Series hero, Dizzy Dean, in the first inning when Lindstrom’s screeching liner back to the mound struck him and forced Dean to leave the game. Hartnett stroked a double in the bottom of the eighth to drive in Lindstrom for the game-winning run, 4-3.

The game drew 15,500 fans to Wrigley Field, down from 46,000 and 45,000 respectively for Opening Days in 1929 and 1931. The Cubs had led the NL in attendance every year from 1926 to 1932, including a major-league record 1,485,166 in 1929 (a figure they did not exceed until 1969). But the North Siders, like the rest of baseball, experienced deep declines in attendance as the effects of the Great Depression worsened in subsequent years.

After plodding along through almost three months of the season, the Cubs – suddenly and without warning – turned it around. Facing the Pittsburgh Pirates at Forbes Field on July 6, the Cubs squandered a six-run lead in the bottom of the ninth to send the game into extra innings. In the 13th inning, Cavarretta singled home the deciding run to give the Cubs a psychological boost and commence a stretch of 24 wins in 27 games. Edward Burns, apparently eating crow after his preseason predictions, described the Cubs’ explosive batting and strong pitching as “brutal and effervescent” as they rolled over their opponents to post a 26-8 record in July and finish the month a half-game out of first place.8

The final day of July proved to be a costly one. In the first game of a doubleheader against the Pirates at Forbes Field, Hartnett injured his ankle sliding into home in the fifth inning. He remained in the game, but an examination afterward “found the ankle bone sheared off and the ligaments separated.”9 In those days, a broken ankle was not necessarily a season-ending injury; and Dr. J.J. Schill, the team physician, expected the catcher back in ten days.

As if on cue, Hartnett returned on August 11 in the Cubs’ victory over the Cincinnati Reds, which marked only the team’s fifth win in 13 games since the catcher’s injury. In second place, 2½ games behind the Giants and a half-game in front of the Cardinals, the Cubs began a 19-game Eastern swing from August 14 to September 1. During the middle of it, they took three out of four games from the Giants at the Polo Grounds, losing only to Carl Hubbell, and concluded their road trip with an impressive 11-8 record. They returned to the friendly confines of Wrigley Field in third place, with just 1½ games separating them from the first-place Cardinals, and Giants.

The Cubs began the fateful month of September with a 20-game homestand. After a loss in the second game of their Labor Day doubleheader, the Cubs won their final 18 games at home. Friday the 13th of September was anything but unlucky as French tossed a complete game to defeat the Brooklyn Dodgers, 4-1, and move the Cubs into a tie for first place. The North Siders took the lead the next day with another victory over the Dodgers with the football-like score of 18-14.

Schedule makers could not have made the season any more exciting as the Cubs and their archrival Cardinals concluded the season with a pennant-determining five-game series at Sportsman’s Park. Despite the Cubs’ streak, they arrived in St. Louis holding only a three-game lead over the Redbirds. While the Giants faded in September, the Cardinals were on their own roll, having posted a 39-16 record since August 1, which was even better than that of the Cubs (35-16). Warneke shut out the Cardinals, 1-0, in the first game of the series, on September 25, to notch his 20th victory of the season. Cavarretta supplied the game’s only run with a home run in the second inning. A rainout forced a doubleheader on September 27. Big Bill Lee’s strong performance and the Cubs’ relentless pounding of 28-game-winner Dizzy Dean ended the drama in the first game. The Cubs overcame a 2-0 deficit by scoring six unanswered runs in a 6-2 victory to capture the pennant with their 20th consecutive win. The victory, wrote sportswriter Irving Vaughan, “climax[es] one of baseball’s most spectacular drives of all time.”10 The Cubs won the second game of the doubleheader before losing the last two inconsequential games of the season.

The Cubs’ 21-game winning streak is the second longest in major-league history, trailing only the New York Giants’ 26 games in 1916. However, the Giants’ streak comes with an asterisk as they accomplished the feat in 27 games, which included a tie with the Pirates in the 13th game. (The Chicago White Stockings, the precursors to the Cubs and one of the inaugural teams in the National League, won 21 consecutive contests in 1880).

The Cubs lacked the star power of their opponents in the World Series, the Detroit Tigers. No Cubs player approached the national prominence of Detroit’s player-manager, catcher Mickey Cochrane; good-looking first baseman Hank Greenberg; or wildly popular pitcher Schoolboy Rowe. Nonetheless Chicago was a nominal favorite in the World Series. In a poll conducted by the Associated Press, 30 of 57 writers surveyed predicted Chicago to be victorious.11 The majority, much like Edward Burns prior to the season, would be proved wrong.

GREGORY H. WOLF was born in Pittsburgh and is a lifelong Pirates fan. After turning his back on the Smoky City, he now resides in the Windy City area with his wife, Margaret, and daughter, Gabriela. A professor of German and holder of the Dennis and Jean Bauman endowed chair of the humanities at North Central College in Naperville, Illinois, he recently served as editor of the SABR books on the 1957 Milwaukee Braves, 1929 Chicago Cubs, and the 1965 Minnesota Twins.

Notes

1 Glenn Stout, The Cubs: The Complete Story of Chicago Cubs Baseball (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2007), 139.

2 “In the Wake of the News,” Chicago Tribune, September 16, 1935, 18.

3 Edward Burns, “Our Cubs Dream of Many Things, but Not of Flag,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 4, 1935, 20.

4 Peter Golenbock, Wrigleyville: A Magical History Tour of the Chicago Cubs (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996), 251.

5 “New Yorkers Tumble Far Behind Leaders,” Palm Beach (Florida) Post, September 19, 1935, 6.

6 Golenbock, 253.

7 Golenbock, 253.

8 Edward Burns, “White Sox Split; Cubs Whip Reds, 11-7,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 29, 1935, 15.

9 Edward Burns, “Hartnett Hurt as Cubs, Pirates Split; Sox Win,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 1, 1935, 1.

10 Irving Vaughan, “Title for Cubs! 21 in a Row,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 28, 1935, 1.

11 Associated Press, “Poll Baseball Writers; Cubs Picked, 30-27,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 2, 1935, 22.