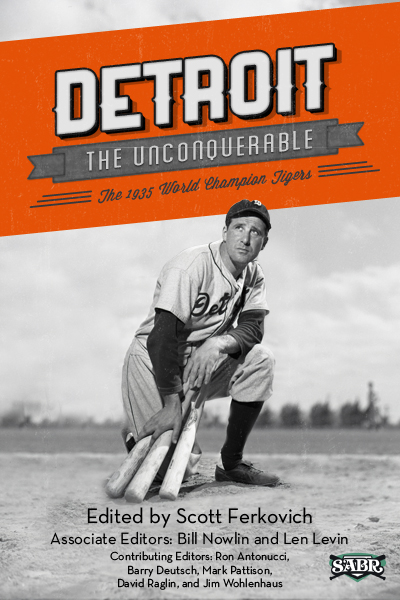

1935 Tigers: Season in Review

This article was written by Greg Erion

This article was published in 1935 Detroit Tigers essays

Led by unanimous MVP Hank Greenberg and player-manager Mickey Cochrane, the Detroit Tigers repeated as American League champions in 1935.Despite what a lot of knowledgeable people in the world of professional baseball felt, Mickey Cochrane was nervous.

In the spring of 1935, a poll of 194 members of the Baseball Writers Association of America indicated that the Detroit Tigers and St. Louis Cardinals, pennant winners in 1934, would repeat. The poll, published in The Sporting News, included writers from all major-league cities. It gave the Cardinals a wide margin over the New York Giants, and the Tigers a narrow lead over the Cleveland Indians, who actually received more first-place votes than Detroit.1

In the spring of 1935, a poll of 194 members of the Baseball Writers Association of America indicated that the Detroit Tigers and St. Louis Cardinals, pennant winners in 1934, would repeat. The poll, published in The Sporting News, included writers from all major-league cities. It gave the Cardinals a wide margin over the New York Giants, and the Tigers a narrow lead over the Cleveland Indians, who actually received more first-place votes than Detroit.1

How Detroit fared in the poll mattered little to Tigers player-manager Mickey Cochrane. The message it sent, that Detroit would repeat, probably did. Cochrane, veteran of a Philadelphia Athletics team that took three straight pennants in 1929-31, had seen complacency develop on that club and feared the same attitude might overcome the favored Tigers.

The writers’ sentiments were not without foundation. A team that finished first by seven games in 1934 came to spring training virtually unchanged. Detroit had been an offensive juggernaut with a team batting average of .300 and an average of more than six runs scored per game. The infield of Hank Greenberg at first base, Charlie Gehringer at second, Billy Rogell at shortstp, and Marv Owen at third averaged 116 RBIs on the strength of a combined .327 batting average.2

Outfielders Pete Fox, Jo-Jo White, and future Hall of Famer Goose Goslin, as well as backup Gee Walker provided solid defense and a composite .300 average in 1934. Cochrane handled the bulk of the catching chores while chiming in at .320.

Detroit’s pitching staff was anchored by a pair of 20-game winners, Schoolboy Rowe (24-8) and Tommy Bridges (22-11), backed up by veteran Firpo Marberry (15-5) and Elden Auker (15-7), who all combined for 76 of the team’s 101 wins. Midseason acquisition General Crowder went 5-1 for Detroit in 1934; he would be a crucial part of the 1935 staff.

Cleveland was the favored competition, having placed second in the writers’ poll and first in a survey conducted by the Associated Press.3 Manager Walter Johnson’s team featured the likes of Hal Trosky (.330, 35 home runs), Earl Averill (.313, 31 home runs), and Joe Vosmik (.341). Mel Harder (20-12), Monte Pearson (18-13), and Willis Hudlin (15-10) headed the pitching staff. Johnson had taken over a moribund team in mid-1933 and driven them to third in 1934. Cleveland was widely considered an up-and-coming team.

The New York Yankees were not deemed of championship quality; their lineup generated too many unanswered questions. The general feeling was that they would finish third. Although Lou Gehrig had won the Triple Crown in 1934 and Lefty Gomez led the league with a 26-5 record, there was concern over whether veteran second baseman Tony Lazzeri (.267) had seen better days, and whether Jack Saltzgaver could handle third. The big question revolved around the replacement for Babe Ruth. Although his play had deteriorated in 1934 (.288, 22 home runs), he epitomized the Yankees, and his departure for the Boston Braves after the season left a big hole in the lineup, if only symbolically.

Cochrane and most of his players differed with the writers’ negative outlook on New York. Mickey offered, “The New York Yankees will be the club to beat.”4

Cochrane was worried more about his own team than about the competition. Detroit had done well in spring training games. Although he was pleased with the pitching of rookies Clyde Hatter and Joe Sullivan, as well as the hitting of outfielder Chet Morgan, the 1934 Texas League batting champion, Cochrane felt the team had no “pep.” After seeing lackluster effort in several games, he tore into the players, accusing them of loafing and not hustling.

Cochrane singled out Goose Goslin for indifferent play and benched him. Goslin, who had been slowly working himself into shape, was stunned by Cochrane’s outburst – but taking his charges to heart, he promised to give his all. Cochrane’s message to a respected veteran was not lost on the team.5 His concern lessened when Detroit thrashed the Cardinals in an exhibition game, 13-8. The victory over their rivals in the 1934 World Series seemed a good omen.6 As spring training ended, Detroit’s attitude had shifted to one of determination to succeed. Cochrane was satisfied – for a while.

As the teams ended spring training, a “feud” between Detroit and Cleveland came to light in The Sporting News. Allegedly, Cochrane had given an interview during which he disparaged the Indians’ pennant chances.

Cochrane was keenly aware of Giants manager Bill Terry’s question before the start of the previous season: “Is Brooklyn still in the league?” This infuriated the Dodgers, motivating them to knock the Giants out of the pennant race in the last week of the season. Hoping to avoid a similar reaction from the Indians, Cochrane sought to disavow the interview in a letter to Walter Johnson, asking that he post it in Cleveland’s clubhouse.

Johnson destroyed the letter, stating, “Let the boys read of Cochrane’s denial in the daily papers if they wished.” Perhaps Johnson was trying to rile up his ball club, which had lost 16 of 22 games to Detroit in 1934.7

Johnson’s action had the opposite effect. Cochrane’s gesture spurned, a steely resolve came to Detroit’s manager. “All right. If they want to be that way, we can take care of ourselves.” One of the most competitive men ever to play ball had been provoked.8

Beginning with Opening Day, Detroit’s resolution to win was sorely tested. Rowe was pounded for seven runs as the Chicago White Sox, picked to finish last, won 7-6 at Navin Field. The next day Bridges won 5-4 on a bases-loaded walk to Cochrane in the bottom of the ninth. It was a less than impressive way for Detroit to post its first victory of the season. Chicago won the next game, prompting White Sox manager Jimmy Dykes to comment, “You mean they were champions last year?”9

After losing two of three to Chicago, the Tigers proceeded to lose seven of their next nine games. Cochrane, seeking to break the slump, juggled lineups and batting orders to improve the offense. He put rookie Chet Morgan in left field, replacing Walker, who was injured. It did not help. With a record of 2-9, the Tigers found themselves in last place on the morning of April 28, six games behind Cleveland. The hitting was lethargic. Cochrane, Goslin, and Greenberg were not producing, each well under .300.

The chief casualty of the slump was Morgan. Installed in the lineup to improve offense, he made a key error against the White Sox, helping pave the way for a three-game sweep by Chicago. Fox replaced Morgan the following day, and was in turn replaced by a recovered Walker. That change proved beneficial. Walker went on an offensive spree, batting over .400 until mid-May – he was one of the few Tigers at that point who was hitting.10 Morgan was out of the majors within a few weeks.

As a feeling of “What’s wrong with the Tigers?” started to gain momentum among fans and sportswriters alike, a shift of fortune began. After six straight losses, Cochrane decided to shuffle his pitching rotation, giving rookie Joe Sullivan a start. Sullivan, a knuckleball pitcher, had won 25 games for Hollywood in the Pacific Coast League the year before. Facing the league-leading Indians, Sullivan scattered 11 hits to gain his first major-league victory, 5-3. Auspiciously, Greenberg connected for his first home run of the year. The victory proved significant in turning the team around.

Greenberg was crucial to the team’s success. The Tigers’ main run producer, he was their answer to New York’s Lou Gehrig and Cleveland’s Hal Trosky. While the heart of the lineup consisted of “G-Men” Gehringer, Goslin, and Greenberg, Hank was the key to the club’s success.11 His slow start (three RBIs in the first 11 games without a home run) was one of the reasons for Detroit’s subpar performance. Greenberg, driven to succeed, saw RBIs as a symbol of achievement. He would tell Gehringer, batting in front of him, “Just get on base. I’ll knock you in.”12

From Cleveland the Tigers traveled to St. Louis to play the Browns. Detroit demolished them in their first game, 18-0, as Greenberg hit a grand slam, his second home run in two days. The next day Detroit won again, with Greenberg chipping in two RBIs. Beginning with Sullivan’s win at Cleveland, Detroit won five straight to climb out of the cellar.

The team played .500 ball for the next several games and then got hot again. On May 19 Sullivan started against Washington at Griffith Stadium. Gehringer and Greenberg hit triples to highlight a four-run first inning, keying what became a 16-6 pounding of the Senators. Fox and Rogell had four hits apiece, and Ray Hayworth, Cochrane’s backup, drove in four runs. Sullivan won his fourth game of the season, giving Detroit another five game winning streak; the victory evened the team’s record at 13-13, a remarkable achievement given the 2-9 start. Their run brought the the Tigers to fourth place, three games behind the surprising first-place White Sox.

A 5-3 win on May 23 over Boston at Fenway Park capped the five-game winning streak. Greenberg’s eighth home run, a two-run shot, was the big blow.13 His 33 RBIs now led the major leagues. That same day, another event took place that affected the pennant race.

Cleveland, a strong favorite to vie for the pennant, had gotten off to a fast start with an 8-1 record. After Detroit bested the Indians behind Sullivan’s effort, they went into a slump, falling behind Chicago and New York. On May 23 Walter Johnson announced that he had released third baseman Willie Kamm and catcher Glenn Myatt, saying, “They were no longer useful to me as players and I felt they were an antagonizing influence upon the ballclub.” The action reflected dissension and undermined Johnson. Morale had undergone serious damage. Although Cleveland played well for several weeks, hopes for a pennant dwindled. Johnson would not finish out the season, and Cleveland ended well out of the race.14

Over the next several weeks, Detroit played little better than .500 ball, holding on to fourth place behind the Yankees, White Sox, and Indians. During this time, they made one of their few player transactions of the season. Aside from the sale of little-used pitcher Carl Fischer to Chicago in early May, the roster remained unchanged until June 11 when 13-year veteran pitcher Firpo Marberry was released.

Marberry had done stalwart work for Cochrane in 1934 with a 15-5 record as a starter and reliever. Developing a sore arm in 1935, he was ineffective. (Marberry joined the American League umpiring staff less than two weeks after his release.15) His loss was eased by Sullivan’s emergence as a spot starter behind Bridges, Rowe, Auker, and Crowder. These five ultimately accounted for 137 of the team’s 152 starts, and 80 of its 93 wins.16

On June 30 Detroit swept a doubleheader against the last-place Browns, 18-1 and 11-6. Pete Fox (now leading off) homered, scored four runs, and drove in six in the first game. In the midst of a 29-game hitting streak, he scored four runs in the second game on five hits, including a double and another home run. Fox was nonchalant about his hitting improvement: “I believe I hit as many balls solidly last year but more of them were caught. This year they have been falling safe. That’s the difference.”17 Fox batted .409 during the streak, with 29 RBIs and 43 runs scored.

Marberry umpired the St. Louis series, in which the Tigers took four out of five. One wonders the thoughts that went through his mind as his former teammates crushed the Browns.

The doubleheader sweep started a ten-game winning streak. Detroit proceeded to beat Cleveland five straight and St. Louis three in a row to draw within a game of the Yankees at the All-Star break. Chicago and Cleveland were slowly fading out of the picture.

Cochrane explained why he felt his club would catch the Yankees: “We can give our pitchers better batting and fielding support than the Yankees can. We kept in the fight while our pitchers were having trouble and now that they are right, we’ll catch the Yankees and pass ’em. I believe we’ll win the pennant by a wider margin than we did last year.”18

Bridges, Cochrane, Gehringer, and Rowe represented Detroit at the All-Star Game. Greenberg did not make a squad manned by first basemen Gehrig and Philadelphia’s Jimmie Foxx despite his league-leading 103 RBIs, 37 ahead of the runner-up, Athletics outfielder Bob Johnson. Gehringer was the lone Tiger to play in the game, going 2-for-3 in the American League’s 4-1 victory. Reflecting how highly Gehringer was regarded, this was the third straight All-Star Game the second baseman started and finished since the game began in 1933 at Chicago.

On July 11, three days after the All-Star Game, Fox’s 29-game hitting streak ended as he went 0-for-4 in a 7-6 win over the Senators. The win came on submarine-throwing relief pitcher Elon “Chief” Hogsett’s 2⅔ innings of scoreless relief of Rowe, before Hogsett singled in the winning run in the tenth inning. After their ten-game winning streak ended, Detroit leveled off, going 6-5 before coming to New York in late July for a crucial series. New York was just a half-game ahead of the Tigers.

Play against the Yankees came in the midst of Cochrane’s continual efforts to juggle his lineup as players fell into and came out of slumps. In June he benched usually dependable third baseman Marv Owen, whose average had sunk to .201, and inserted reserve infielder Flea Clifton into the lineup. Clifton hit near .300 the next several weeks before Owen got his job back and played effectively the rest of the way. Cochrane juggled Fox, Walker, and White in and out of the lineup all season long as their play blew hot and cold. Even Goslin sat out a few games when he slumped. Cochrane was solid behind the plate, although Hayworth frequently spelled him. Hayworth, appearing mostly against left-handed pitching, played in 51 games and batted .309.

Despite Cochrane’s assurances that “our pitchers were having trouble and now that they are right,” his major concern the entire campaign continued to revolve around pitching.19 Auker, Bridges, and Crowder were steady, but when Marberry was released and Rowe proved inconsistent, Cochrane had a challenge on his hands. Sullivan’s quick start gave the Tigers much needed support early on, but he faded as the season moved along. Rowe took a long time to get back to his level of performance in 1934 when he won 24 games. By the end of July, he owned a mediocre 9-9 record. At the same point a year earlier, Rowe was 14-4. In August he regained his form, going 7-1 for the month, at last giving Cochrane a solid four-man rotation.

There was no depth to the staff, however, as Hogsett and Sullivan were inconsistent, while little-used Vic Sorrell was effective only in spot appearances. Except for Roxie Lawson, called up from Toledo at the end of August when the pennant race was for all practical purposes over, Cochrane operated from mid-July with just a seven-man pitching staff. Lawson did provide late-season relief to the starting rotation. Used in spot starts, he pitched well, going 3-1 as the campaign wound down. His first appearance of the year opened eyes as he bested Red Sox ace Lefty Grove with a five-hit 2-0 shutout.

All the pressure of playing and managing told on Cochrane. “When I was a player I worried only about myself. Good money and easy work. Now I have to worry about everybody,” he said. “I have to see that they’re all in shape and stay in shape. If one of them eats something that makes them sick, it makes me sick.”20

With the pennant race practically tied, Detroit came to New York for a five-game series in late July. The first game was rained out. The next day, July 23, the teams played a doubleheader before a crowd of 62,516.21 The Yankees won the first game, 7-5, despite solo homers by Cochrane, Gehringer, and Greenberg as Johnny Allen bested Rowe. In game two Cochrane countered Yankee Lefty Gomez with Sorrell, who had narrowly avoided going to the minors at the end of spring training.22 The 34-year-old Sorrell, who was one of the first pitchers to wear glasses in the major leagues, outpitched Gomez, 3-1, scattering eight hits.

The Tigers’ win in the second game, keeping them half a game behind New York, reflected the challenges the Yankees faced that summer. During the game, Gehrig walked three times, negating his offensive threat. It was typical of the season. Without Ruth, Gehrig got a league-leading 132 bases on balls, the most ever in his career. His 30 home runs and 119 RBIs in 1935, superlative for any player, were the lowest of his peak seasons between 1927 and 1937. Yankees owner Ed Barrow attributed Gehrig’s less-than-expected performance to an extended barnstorming tour of Japan that wore him down.23

A second and perhaps more revealing indication of the Yankees’ troubles was that the loss dropped Gomez’s record to an uncharacteristic 8-10 record. Although Gomez posted the fourth-lowest ERA in the league, he ended the season at 12-15, victim of an intermittent sore arm. It may have been brought on through overuse by Philadelphia skipper Connie Mack on the same barnstorming tour of Japan that Barrow claimed had worn down Gehrig.24 A mere reversal of Gomez’s performance that year would have made for a much tighter race.

In the fourth game of the series Crowder, the old man on the staff at 36, bested Red Ruffing with a four-hit shutout, winning 4-0. Jo-Jo White, leading off, hit his first home run of the year. A half-hour thundershower interrupted play in the second inning. When the game resumed, Ruffing had trouble regaining his rhythm and lost his effectiveness, allowing several walks and hits, the last a two-run single by Goslin sealing New York’s fate.25 The last game of the series, scheduled the following day, was rained out.

At this point Detroit had played five more games than New York; the Yankees were in first place by percentage points, but a half-game behind Detroit. Leaving New York, the Tigers traveled to Cleveland for a four-game set with the Indians. Cleveland had won five of its last six and, 7½ games out, was hoping to edge back into the pennant race.

Cochrane opened with Auker, his hottest pitcher, who had won eight of his last nine decisions, against Thornton Lee, in his second full season with Cleveland. It proved no contest as Detroit prevailed, 8-2. The Tigers scored a run in the second on Goslin’s double and Billy Rogell’s single. Fox put the game out of reach with a two-run triple in the sixth as Auker improved his record to 10-4.26 Meanwhile the Yankees lost to the seventh-place Senators, 9-3, giving Detroit a 1½-game lead. The Tigers were never headed from then on. Detroit won three of four to knock Cleveland out of the pennant race. Within a week Water Johnson was out as manager, a victim of player injuries, personnel issues, and perhaps his spring dispute with Cochrane.

Elden Auker had his best season as he went 18-7 for a league-leading.720 winning percentage. Auker felt that Cochrane contributed greatly to his winning ways at Detroit. “He was such an inspiration to me when I was pitching,” the pitcher said. “His drive and desire to win was so overwhelming that it would carry me through my troubles. He made me a good pitcher, he gave me confidence and strength, like no other catcher did. I was not the same pitcher without him behind the plate.”27

Detroit built a six-game lead. The Tigers were outstanding in August, going 23-7. The offense averaged more than six runs a game that month, but the pitching staff led the way, delivering 20 complete games, seven shutouts, and an ERA of 2.46. The Tigers simply crushed their opposition.

Early in August Chicago came to Detroit for a four-game series. The surprising White Sox offered the last meaningful challenge of the season to Detroit. A 19-9 run in July pulled them within 3½ games of Detroit. But Crowder, Rowe, Bridges, and Auker threw consecutive complete-game wins, Bridges and Auker giving up just three and four hits respectively, to end Chicago’s challenge. Chicago went on to finish fifth, better than their eighth-place finish in 1934. Rival managers Joe Cronin, Bucky Harris, and Rogers Hornsby conceded the race, Cronin offering, “The Tigers are a cinch.” Virtually alone among his peers, Yankees manager Joe McCarthy still felt there was a chance to overtake Detroit.28

As the team moved toward a second straight pennant, excitement rose in Detroit. The Sporting News described the sense of anticipation: “Civic and fraternal organizations are arranging banquets and celebrations, hotels and railroads are preparing for increased business and the public in general whether the Cardinals, the Cubs or the Giants will oppose the American League champions.”29

Cochrane and team owner Frank Navin suggested that caution be exercised, that expectations were premature, no doubt recalling the New York Giants’ late-season collapse the year before. Their cautionary outlook was ignored.30 As events were to prove, they had reason for their reticence.

Detroit continued its winning ways through early September. After sweeping the A’s 9-7 and 15-1 in a doubleheader on September 7, they were ten games ahead of New York. From then on, a malaise overtook the ream, which won only eight of its last 22 contests. The team seemed to have come full circle to its performance at the beginning of the season. After losing three of four at Boston, Cochrane, thoroughly aroused, ordered batting and fielding practice on September 20, telling one and all that his team had been “fooling around” long enough, that it was time “to get down to business.”31 The players heeded his charge.

The next day, before an overflow crowd of more than 31,000 fans, Bridges threw a seven-hitter to win his 21st game of the season, 6-2, in the first game of a doubleheader against the Browns. Auker, not to be outdone, came back with a six-hit shutout to win his 18th game, 2-0, to clinch the Tigers’ second straight championship, their fifth overall. It was a great way for Auker to celebrate his 25th birthday.

The pennant won, Detroit lost six of its last seven games. The late-season slide reduced the final margin over New York to three games, the Tigers’ slump coming too late for the Yankees to take advantage. The margin did not reflect a race that for all practical purposes had ended in August. Cochrane’s earlier prediction that Detroit would win the pennant by a larger margin than in 1934 was not to be.

Cochrane’s disappointment aside, how did the Tigers take their second straight title?

Although their offense first comes to mind, in truth the Tigers won with solid fielding and pitching as well as offense. The pitching staff threw 87 complete games and 16 shutouts to lead the league, their 3.82 ERA second only to the Yankees. Bridges and Rowe were among the league leaders with 21 and 19 wins respectively. Auker’s 18-7 performance, particularly in midseason as Rowe struggled, was crucial to the team’s success. Crowder showed a creditable 16-10 record, with several pivotal victories in what was his last full season of play.

Detroit led the league with a .979 fielding percentage, driven by a team-low 127 errors. The Tigers completed 154 double plays, second best in the league. Their hitting, while down from their effort the previous season, was substantially better than that of any other team. They scored 919 runs, 96 more than runner-up Washington. A league-leading 628 walks and .435 slugging percentage aided Detroit’s run-scoring ability.

Four starters, Gehringer (.330), Greenberg (.328), Fox (.321), and Cochrane (.319), went over the .300 mark, as did Walker, who hit .301 in 98 games. Cochrane walked 96 times, an impressive total given that he played in only 115 games. Greenberg (170), Goslin (109), and Gehringer (108) each went over 100 RBIs. Greenberg’s league-leading 170 RBIs were especially impressive; they were 51 more than Gehrig’s 119, and 40 more thant National League leader Wally Berger’s 130. No player before or since (as of 2013) led his league, or the majors, by such a margin. It was the first of Greenberg’s four RBI titles. His 36 home runs tied him with the A’s Jimmie Foxx.32 As with RBIs, it was the first of four times Greenberg led the league in home runs. Greenberg was unanimously selected the American League’s Most Valuable Player.

Cochrane surely recognized the components that went into this championship. Asked by a sportswriter whether it was easier to “mastermind” better on the bench or behind the plate, he responded, “Say, this masterminding business is a lot of bunk. What it takes to win ballgames is hitting, pitching, throwing, and fielding – not deep thinking.”33 However victory was achieved, Detroit’s fans fully enjoyed the team’s efforts. A major-league-leading 1,034,929 flocked to Navin Field to root their team on. It was only the second time Detroit’s attendance had climbed over a million.

A talented roster of players allowed Detroit to win two pennants. However, more than talent carried the day. Virtually every description of the Tigers’ efforts begins with one intangible factor: Mickey Cochrane. Detroit sportswriter H.G. Salsinger perhaps described Cochrane best: “As a field leader, Cochrane probably never had an equal. No other playing manager was ever able to lift a team the way Cochrane could. His aggressiveness was contagious. Under his leadership, the Tigers soon developed into a fiercely competitive club. He had the inspirational touch.”34 His relentless energy and resolve to succeed began in spring training when he was concerned with the lack of “pep” on the team. It continued through the latter part of the season when Cochrane drove the league-leading team to achieve even greater heights. Cochrane’s relentless determination had begun soon after he joined the fifth-place Tigers in 1933, when he boldly declared, “We’re going to win.”

Now the Tigers would face the Chicago Cubs in the World Series.

GREG ERION and his wife, Barbara, live in South San Francisco. Retired from the railroad industry, he currently teaches US history part time at Skyline College. Greg has contributed several articles to the SABR Baseball Biography Project and is currently working on a book about the 1959 season.

Notes

1 “Consensus of 194 Experts Favors Cards, Tigers to Repeat,” The Sporting News, March 21, 1935, 3.

2 All statistical data derived from Retrosheet.org or Baseball-Reference.com.

3 Henry W. Thomas, Walter Johnson, Baseball’s Big Train (New York: Phenom Press, 1995), 326.

4 “Walker Steps Into Cochrane’s Favor,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1935, 8.

5 “Cochrane Jacks Up His Pepless Tigers,” The Sporting News, March 28, 1935, 6.

6 “Tigers Shake Training Shackles, Reviving Cochrane’s Confidence, “The Sporting News, April 4, 1935, 1.

7 “Big Train Fires Up ‘Feud’ With Detroit,” The Sporting News, April 11, 1935, 7.

8 “Walker Steps Into Cochrane’s Favor,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1935, 8.

9 “Tigers Now Realize 1934 Doesn’t Count,” The Sporting News, April 25, 1935, 2.

10 John C. Skipper, Charlie Gehringer, A Biography of the Hall of Fame Tigers Second Baseman (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2008), 49-50.

11 G-men was a popular term in the 1930s for FBI agents.

12 Skipper, 87.

13 “Detroit Climbs Into Fourth Place in American League by Beating Red Sox,” Los Angeles Times, May 24, 1935, A16.

14 Thomas, 326.

15 James Charlton, ed., The Baseball Chronology: The Complete History of the Most Important Events in the Game of Baseball (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1991), 285.

16 The discrepancy between 152 starts and 151 decisions is because of a tie game, the second game of a doubleheader against Cleveland on June 5 that ended 4-4, called because of darkness. See “Detroit Cops Opener, Darkness Ends Finale,” Los Angeles Times, June 6, 1935, A11.

17 “Tigers Make Bold Prophet of Mickey,” The Sporting News, July 11, 1935, 1.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Charlie Bevis, Mickey Cochrane, The Life of a Baseball Hall of Fame Catcher (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1998), 130.

21 “62,516 Watch Tigers Divide with New York,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 24, 1935, 16.

22 “Mickey Again Lucky in Keeping Sorrell,” The Sporting News, August 1, 1935, 1.

23 Charles C. Alexander, Breaking The Slump: Baseball in the Depression Era (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), 109.

24 Vernona Gomez and Lawrence Goldstone, Lefty, An American Odyssey (New York: Ballantine Books, 2012), 194-202.

25 “Crowder Stops Yankees; Tigers Near First Place, Chicago Daily Tribune, July 25, 1935, 17.

26 “Detroit Bumps Indians; New York Loses, 9 to 3,” Los Angeles Times, July 27, 1935, 7.

27 Bevis, 132.

28 “Cochrane Has New Job – Stilling Fans,” The Sporting News, September 5, 1935, 1.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid.

31 “Mickey Keeps Tigers on Toes, Warns Them Against Let-Down,” The Sporting News, September 26, 1935, 1.

32 On the last day of the season, Greenberg led Foxx by two home runs. Foxx, in what would prove to be his last game as a Philadelphia Athletic, hit two home runs, aided by a Washington Senators catcher whose dislike of Greenberg led him to signal Foxx what the pitcher was going to throw. Greenberg found out about this nearly 50 years later when a friend who had played for the Senators at the time told him about the incident. Hank Greenberg (Ira Berkow, ed.), Hank Greenberg: The Story of My Life (New York: Times Books, 1989), 77.

33 “American League,” The Sporting News, September 5, 1935, 6

34 Ed Fitzgerald, ed., The American League (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1959), 186-187.