1967 Red Sox: Spring Training

This article was written by Bill Nowlin

This article was published in 1967 Boston Red Sox essays

After a 90-loss, ninth-place season in 1966, the Boston Red Sox entered spring training in Winter Haven, Florida, with a new manager and a new outlook. Spring training 1967 was quite different from spring training 1966 for the Boston Red Sox.

Spring training 1967 was quite different from spring training 1966 for the Boston Red Sox.

We can remember 1966 as the year when Earl Wilson was turned away from the Cloud Nine bar in Winter Haven because of the color of his skin. He’d been playing pool with Dennis Bennett and Dave Morehead, and they crossed the street to get a beer at Cloud Nine where Wilson was denied service. All three left. Wilson was denied entry to another establishment as well. It made the front page of the Boston Globe in February, and Red Sox manager Billy Herman said, “Any place which is not suitable for one of our players is in turn unsuitable for all of our players.” GM Dick O’Connell was embarrassed because he had just brought the Red Sox back to the Grapefruit League after six years of spring training in Scottsdale, Arizona. He’d been assured by Winter Haven that there would be no racial difficulties.

Some days later, Herman was asked about players drinking. A reporter asked him directly, “Are the Red Sox down here to train to play baseball — or are they down here to drink?” That wouldn’t be a Boston reporter trying to stir up a little trouble, would it? Herman’s response might not have set the tone the Red Sox wanted to convey, but was forthright and likely reflected one of the legacies of the Yawkey/Higgins years. “I don’t care if a player of mine has a drink,” said Herman, who’d been known to sock away a few himself from time to time. “There’s nothing wrong with that,” he added. So, he was asked, you don’t have any objection to players drinking, either in spring training or during the regular season? “No, I haven’t,” he replied. “All I demand is that they get in shape — and keep in shape — to play baseball. If a player has a drink one night and plays ball well the next day, that’s all right with me. It’s all right, in moderation. In fact, if I meet one of my players in a bar, I’ll buy him a drink.” A short while later, Herman also volunteered, “There have been some pretty good ballplayers who have been drinkers.” It would be understandable if some interpreted this as not exactly discouraging drink.

Another day, another quote. Herman later remarked, “I’ll let the players decide themselves if they’ll have a curfew this year.” Herman, in the words of Bill Ballou, was “a member of baseball’s old guard and a manager built for comfort, not speed.”

After the ’66 season was over, it didn’t take long for O’Connell to make a move. Herman had already been relieved as manager on September 9, and Dick Williams was hired for 1967 on September 28, the very day after Boston’s season ended. VP Haywood Sullivan made it evident there would be some changes made. On October 3, he said there were no untouchables on the Red Sox, and that the only “Untouchables” were Elliot Ness and company on the old TV show of the same name. “There are men the ball club would like to keep,” Sullivan said, “but if some outfit is in a frenzy to make a deal, then anyone can go.” That wasn’t exactly earth-shaking news; baseball executives had uttered similar words for years. What was startling, though, was the September 29 headline from Dick Williams’ first day on the job: “Williams Strips Yaz of Red Sox Captaincy.” It wasn’t meant to demean the former Captain Carl but it was clearly intended to send a message. With him and his four coaches, he said, “There are five chiefs around, and no need for any more. I don’t see any need of having another chief on the team.”

Williams was asked if he realized he might need to be a bit of a baby-sitter on a team often accused of having a bit of a country club atmosphere. His no-nonsense reply: “There are some players who need a slap on the back, and others who need a slap somewhere else.” He said he’d immediately tell a player if he was messing up, “but I will not have these team meetings unless it means cutting up money for first division spots.” Williams had been given only a one-year contract and columnist Bud Collins said reporters had already begun a pool betting to see how long he’d last. “I consider this a challenge,” Williams said. Collins picked up on that bit of understatement: “A challenge? This job is no more of a challenge than Premier Ky has in Saigon or Daniel had in that Babylonian zoo, or Eddie Fisher had with Liz Taylor.” Veteran Globe scribe Harold Kaese’s column bore the headline “Williams’ Nerve Could Be Asset.”

Kaese saw real improvement over the 1965 ballclub, and so had the 150,000 additional fans filling more seats at Fenway. In a September 19 column in the Globe, the morning after the last home game. Kaese noted that their 40-41 home record was a six-game improvement. There had been player turnover, and it had been for the better. The roster on 1966’s final Fenway game had only nine players who’d been with the team a year earlier. They’d kept Yaz and Rico and Tony C, of course, but added George Scott, Joe Foy, and Mike Ryan — bringing youth to some positions. The pitching was looking better as well.

The Sox lost five of its last eight games, though, and it was a fight for the finish — to see which team of four would end up in the cellar. Bud Collins discussed the reverse pennant race — the Dungeon Derby — he called it, in effect assigning a negative magic number for the rights to 10th place. Boston’s season ended earlier than the other three teams. When Boston was all done, they would have to wait out the remaining games for Washington (one more), Kansas City (three more), and New York (four more games to play after the Red Sox were done.) No doubt it would be “sheer agony…torture” and they would have to “chain-smoke their way through Sunday helplessly as the other contenders decide their fate.” As events transpired, even though the Yankees won four of their last five, it wasn’t quite enough. They’d played three fewer games than the Red Sox, and while the Sox had lost one more game than New York, they’d won two more. That put them at a .444 winning percentage while New York was at .440, 26 1/2 games out to Boston’s 26. New York had earned sole possession of the cellar.

Dick Williams had played on the Red Sox team in 1963 and 1964; he wasn’t that much older than many of the players and would now be managing some of his recent teammates. But he earned their respect. Bobby Doerr was named to Williams’ coaching staff and admired the new manager. “There’s something in Dick’s voice, his way. When he says, ‘Be at the park at 9 o’clock,’ you know you’d better be there. He doesn’t have to rant and rave. There’s no falseness about him. Players soon sense falseness in a manager. Managing is like hitting — you either have it or you don’t. Williams has it. There’s no tension on his club [referring to Toronto], but he has the authority. The players respect him.”

When new Boston Red Sox manager Dick Williams faced the press corps during spring training at Winter Haven, Florida, in March 1967, they had no idea what an amazing ride they were all about to take. (BOSTON HERALD)

Postseason roster moves in October 1966 saw the Red Sox cut eight players including Lennie Green, Dick Stigman, and Billy Short. Eddie Kasko was cut but took over for Williams as manager in Toronto. Haywood Sullivan “admitted that hopes for a trade of major proportions were not good” — Boston Globe. Sullivan said, “Frankly, I don’t think we’re going to be trading much this winter. Most of the people now on our roster are young, and you don’t want to trade for someone until you know for sure what he can do, or can’t do.” Promoted to the major-league roster were: Billy Conigliaro, Russ Gibson, Ken Poulsen, and five pitchers: Gary Waslewski, Rob Snow, Mark Schaeffer, Dick Baney, and Billy Farmer.

In late November, Dick Williams said he was happy enough with the hand he’d been dealt: “You think it would be funny if a ninth place team stood pat, don’t you? It could happen. I like my team.” Williams went on to say that he would not tolerate any interference from above, but that he’d managed in the organization for two years already “and I’ve had complete freedom.” If there were interference? “The first time it happens, I’ll pack my bags and go home.”

In January, Williams laughed about his television activities — he’d appeared on “Hollywood Squares” and broke the bank. It came two years after he’d won more money than any male contestant on the show “You Don’t Say.” He was unhesitating when asked what would be his biggest problem: “Making them play as a team, as a unit,” he told Will McDonough. “Our people have got to forget about individual statistics.” After a couple of other comments, he added, “To be perfectly honest, I don’t want any of the players to love me. I don’t care if they all dislike me. We’ll all get along great if they do just what I ask. If they don’t, then I’ll rip them good.” A full month before pitchers and catchers were due to report, Williams didn’t engage in any false platitudes about how everyone would have a chance to make the ballclub. He said he could pretty much name his starting position players — and then proceeded to do so: Foy at third, Rico at short, Mike Andrews at second, and a fight between Tony Horton and George Scott for first base. “I think the competition will be good for Scott,” he added, likely tipping his hand a bit as to his motivation in setting up a contest at first. Yaz would play left field, Reggie Smith in center, and Conigliaro in right. The only other position up for grabs was catcher: Mike Ryan, Bob Tillman, and Russ Gibson were all in the mix. The pitchers would be Lonborg, José Santiago, Darrell Brandon, and Lee Stange, with John Wyatt and Don McMahon in the bullpen. That left a few spots open for pitchers on the team. Waslewski and Rohr he knew from Toronto, and Pete Magrini. Bennett, Morehead, Charton, and Stephenson would all have an equal shot.

In late January, O’Connell had said that Tom Yawkey wanted a “fiery manager.” O’Connell denied Yawkey was selling the team. “He’s never been more interested in his team.” It appears Yawkey had found a fiery manager, or at least O’Connell had. At the Baseball Writers dinner on January 26, Harry Dalton (Orioles), Gabe Paul (Indians), Ralph Houk (Yankees), Joe Cronin (AL), and a number of Red Sox executives all talked about how much better the Boston club was going to be. There were signs there.

Not only had O’Connell found the man he wanted, but he began to introduce a number of innovations. One was what Will McDonough dubbed an “instant critic” — a videotape replay machine. The purchase was announced on February 7, a $3,000 Sony unit that would be used to record both pitchers and hitters so that coaches could sit with the players and evaluate what they were doing right or wrong. Such machines had been used in golf and pro football but, McDonough wrote, “To the Red Sox knowledge, no one has ever attempted to use TV replay in baseball as a technical instructor.” The regular photographer for the Red Sox, Jerry Buckley, had begun taking lessons in January as to how to operate the unit which was to be set up in Winter Haven. Player reaction was generally favorable.

Sullivan also shelled out a modest $175 to buy a batting machine constructed by Joe Torre’s brother Frank. “It looks like a good machine,” Sullivan said. “If they’d had something like this around when I was a player I might have batted .200 in the major leagues.” (The self-effacing Sullivan may have mis-remembered his own stats; his career average was .226.)

One other new ingredient the Red Sox had was the BoSox Club. The fan booster club concept was brought to Boston by Ken Coleman, inspired by Cleveland’s Wahoo Club. Dom DiMaggio became the first president of the BoSox Club when it formed in 1966 and it boasted about 200 members by Opening Day.

Some of the players were a little late returning their contracts, as Clif Keane noted on Valentine’s Day. Six player contracts had arrived, but not Andrews, Demeter, Gibson, Horton, Jones, Petrocelli, Ryan, Smith, Stephenson, Thomas, Waslewski or Yastrzemski. “Can you imagine having 12 holdouts on a ninth place team?” asked Keane. As to Stephenson in particular, Keane added, “He has exactly three big league wins posted in the five years he has been with the club. How a guy holds out under those conditions — well, as we said, Haywood has a very clever way of expressing himself, so he’ll probably have Stevie under contract.” Sullivan remarked, “I’m really not too worried. I don’t mind too much getting their letters, and answering them. It’s a little fun.” By the 27th, only Horton was outside the fold.

A week before camp opened, the spotlight was being readied for Dick Williams to be put under. After Dick O’Connell had relieved manager Billy Herman of his duties in September, he’d said of Herman, “He ran a bad spring training.” The Sox had finished last, with an 8-19 record but little of spring training had been reported to the Boston fan base because of the month-long newspaper strike that covered most of the month of March.

Williams elected not to let the players decide whether or not they felt like having a curfew. In a team meeting on the first day of camp, February 25, he told them that there would be a 12:30 a.m. curfew, and he told them they had to keep their weight down, too. Both the regimen and curfew would last through the season: “I’m not looking to get the men in shape and then have them dissipate the rest of the year.” He installed a weight chart in front of the manager’s dressing room. The weight issue would result in occasional benchings of players during the season, but should have come as no surprise. Williams had “started managing even before players arrived at Winter Haven” by sending letters to each player, telling each of them what weight he and trainer Buddy Leroux had determined was their optimal weight and what weight they should be when they reported.1 Williams was consistent. A month earlier, he’d said, “There’s not going to be a Gestapo, by any means. Sure, I’ll have a curfew. I had one at Toronto. But I think I checked once in two years. I don’t think a manager has to be watching. He can tell by the way the players perform if they’re getting the proper rest.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, Dennis “The Menace” Bennett was the first player to break a rule. Two days later, he showed up 25 minutes late for a workout, bringing along roomie Bob Sadowski. Williams said, “I told the two men that the next time there might be some fine with it. And they missed a lot of sliding work Monday, so they’ll do it today. After all, I wouldn’t say they are sure of their jobs.”

In March, Dick O’Connell mentioned that season ticket sales had increased 40% over the previous year, which isn’t saying much but an indication that the new look of the club, the youth, and the manager (himself not all that old) were giving fans something to hope for — maybe that they’d win more than they’d lose.

Williams liked two of the young pitchers he’d had in Toronto. He said he didn’t plan to keep Billy Rohr around the big league park when what he really needed was to get more innings. Mace Brown had worked with Rohr in instructional league. He said of Williams, “I know he doesn’t intend to carry Rohr unless he is working regularly. But I say there is a chance he will work in a rotation. He’s no Grove, but I sort of like him.” Williams added, “He’s far and away the best prospect we have in the organization. There may be some doubts about his strength. I’ll have to watch for that. He’s a skinny kid. But I like to think I have a big league pitcher in Rohr.” Of Gary Waslewski, Mace Brown said, “He’s the best of the new righthanders. He may need another pitch and his best bet is a curve.” Williams said that Waslewski had a tendency to coast, and that he’d almost sent him down from Toronto in 1966, but he had really come around and pitched well the second half of the season. There was, he added, no one better at holding runners on base.

There were some of the usual communications issues — Sullivan said he’d not heard from Horton about his contract — but then learned that O’Connell had already called Horton and worked it out. “I wouldn’t have called him,” Haywood said. “He would have stayed in California if he didn’t call me.” Yaz said that O’Connell had promised him he would not be traded. “It’s the first I’ve heard about it,” said Sullivan.

As the exhibition season got underway, Williams felt he needed a little steadying influence in the infield so he turned to Petrocelli. “He’s an intelligent ballplayer and I want him to have some authority out there…I told him I wanted him to take over in tight spots.” It wasn’t the same thing as naming him “captain” but the Globe used the word albeit it in quotation marks in its March 4 headline.

Several Red Sox veterans came out to help tutor the team. Doerr was a coach, of course, but Dom DiMaggio came to camp to work with center fielder Reggie Smith. George Smith tore a knee ligament while practicing rundown plays on March 5. Smith had been the starting second baseman in 1966, but now he’d been penciled in to back up Petrocelli at short. The injury looked to keep him out for eight weeks. As it happened, he never appeared in another major-league game.

Pitching coach Sal Maglie’s wife Kay had been seriously ill with cancer for quite some time. When she died, Sal went to Buffalo for the funeral, made arrangements for their two children, and returned to camp on the 5th. And Ted Williams came in to help with the hitters the next day.

On the same day, March 6, Dick Williams did something unusual: he put on umpire’s gear and worked behind the plate for the first intrasquad game, all the better to judge both pitchers and batters. Williams worked the plate on a number of occasions. He also made use of the videotape equipment supplied by GM O’Connell.

Conigliaro was ready. He wanted to hit cleanup. “I want the pressure of batting fourth,” he said, while Yaz was said to have told Dick Williams back on the second day of camp that he was no troublemaker. The two had played together on the Red Sox just a few years earlier. Williams had needled Yaz once, saying, “You run the bases just like Jackie Robinson, only you get caught.” It was hard for Yaz to take it in stride, and he asked to see Williams. “I told him I had the reputation of not getting along with managers and I didn’t want him to think I was that way,” Yaz told Clif Keane.

Ray Fitzgerald wrote in the March 9 Globe that Sox management thought Lonborg could become a 20-game winner, and “So does Jim Lonborg. A year ago he didn’t…In 1966…when he was good, he was very, very good, but when he was bad — Disaster City.” Lonborg wanted to be in the regular rotation, and start every fourth day, and believed his control was much better. He had more confidence in his ability to keep the ball low. Sal Maglie was working with him on a changeup but the main thing in Lonborg’s favor was his self-confidence.

The first game of the exhibition season was at Payne Park, Sarasota on March 10. Conigliaro hit a home run, even though the White Sox won the game, 8-3. Dennis Bennett took the loss, giving up four runs in three innings pitched. Reggie Smith made two throwing errors. The following day, George Thomas’ solo home run in the top of the ninth inning broke a tie game against Kansas City. Ted Williams proclaimed Reggie Smith the best prospect in years, including both Yaz and Tony C.

On March 12, Doerr said that one player he wouldn’t trade was Tony Horton, saying that he was in a class with Harmon Killebrew. Maybe he wouldn’t hit as many homers, but Doerr predicted he’d hit between 30 and 35. The trouble was, Horton was limited to first base, though, and Scott was the best fielder so it wasn’t going to be easy to take the Boomer off the bag and stick him somewhere else.

On March 14, Conig hit a homer and two doubles, though the Red Sox lost to the White Sox, 5-4. Williams was “seething,” according to Ken Coleman, when Tony Horton overran second base and was tagged out. It was another example of Williams treating an exhibition game as if it were the real thing.

Several pitching arms were of concern. Some were sore, others needed more work. This was spring training, after all. That’s part of what it’s all about. But Williams wasn’t all that forgiving. When Jerry Stephenson walked the first three Yankees in the bottom of the first during a game at Fort Lauderdale, he told reporters that Jerry had better learn how to stay loose if he was going to pitch up north. Williams continued to ride George Scott. Asked if Scott was any better at laying off low pitches, Williams said, “Yes. He’s improved slightly. At least now he waits until they come up to his shins.”2

The next day, on the 16th, the Globe said “the only man who looked like a pitcher was Darrell Brandon” in a slugfest as the Red Sox beat the Mets coming from behind with a 10-run ninth inning — a game that both Yaz and Conig sat out. The Red Sox batters collected 23 hits and earned 13 walks. The final score was Red Sox 23, Mets 18.

Meanwhile, Williams was working with baserunners on speed. In a 7-5 loss to Cincinnati, he was pleased because they’d stolen four bases, with two of those coming on a double steal. “We’ve had speed on the club before,” Williams said. “But have never used it. We’ve always waited for the wall. Now we’re going to use our speed. The home runs will come anyhow.”

Tony Conigliaro was hit by a John Wyatt batting practice pitch before the March 18 game and suffered a fractured shoulder blade. The Sox anxiously awaited word from X-rays taken back in Boston — was it a hairline fracture, in which case he’d just miss a couple of weeks, or was it a compound fracture which would probably cost him the season? Fortunately, this time, it was a minor injury to the scapula. It was, though, the fifth time that Conigliaro had suffered a broken bone when hit by a pitch. He clearly crowded the plate more than he probably should. Dennis Bennett had a good day, throwing five hitless innings against Detroit.

On the 19th, Dave Morehead was sent to Boston’s Toronto farm club, along with Bob Sadowski, Jerry Moses, and Pete Magrini. The day’s game ended oddly as Detroit’s Dave Wickersham had the bases loaded and induced a bunt popup from Bob Tillman that sailed 15 feet into the air — and then he unaccountably stepped back and let the ball drop, allowing the Red Sox to complete a come-from-behind win in the ninth inning. “I don’t know why,” he said after the game. The game also featured some uncharacteristic play, aside from the nearly-botched squeeze that won the game: there was a double steal and a couple of hit-and-run plays with a baserunner on second. Rather than being pleased, Williams groused about the four Red Sox errors. As a team, the Red Sox were hitting well over .300.

The Sox were trying to see if they could get Tony Horton more playing time, and so asked George Scott to play some in right field. Scott wasn’t at all pleased, insisting that he was a first baseman, not a right fielder. The Globe sports page featured a headline in the March 23 paper: “Red Sox Willing to Trade Scott.” The article said that Jose Santiago was trade bait, too. Both Santiago and Scott, plus Garry Roggenburk, were placed on waivers to see what interest might be generated. Will McDonough acknowledged that sometimes being listed on the waiver wire was just a way to “shake up a player.” With Scott grumbling at battling Tony Horton for the first base slot, it may have just been a ploy to shake up Scott. Weird things have happened with waiver wires. In late September the year before, just before being fired, McDonough wrote, “Billy Herman put the ENTIRE team on waivers.” Only four were claimed by other clubs, and all four were withdrawn. Since he was the one sent packing, Herman never had the opportunity to follow up on the interest expressed in the four who’d been claimed, and explore any trade possibilities.

The very day the “Red Sox Willing to Trade Scott” headline ran, Scott was indeed playing right field and ran back deep, slamming into the right field wall which was inconveniently made of cinder block. He suffered a concussion, and was expected to be out five or six days. McDonough commented: “Playing a foreign position — right field — Scott temporarily misjudged the ball. In his haste to adjust, he ran smack into the wall.” He was knocked out for over a minute. Mike Andrews joked, “He moved the wall from 330 feet to 332.”3 X-rays of Scott’s jaw and wrist proved negative, but he was kept in the hospital overnight for evaluation. Williams said that Scott would continue to play the outfield, but he would move him to the easier-to-judge-a-fly left field.

Lucky 7’s: Reggie Smith and Dominic DiMaggio. In 1967 with the Boston Red Sox, Dom gave rookie Reggie a number of spring training suggestions on how to improve his center field play. (BOSTON HERALD)

A week later, in the March 26 and 27 issues of the Globe, Harold Kaese penned a two-part series on Dick Williams. More important than questions about whether rookies Reggie Smith or Mike Andrews would produce as regulars was the question whether the Red Sox had a good manager in Dick Williams. He concluded, “The early returns are in and favorable.” He had his players hitting, but also running, bunting, and thinking. The manager who called himself the “wrong Williams” (alluding to Ted) “is neither magnetic nor easy to warm up to. But he is aggressive, scrappy, cocky and terrier-tough…Williams belongs to the Society of the Under-Rated.” He believes in hard work, condition, fundamentals, Kaese wrote, and he ran long drills, emphasizing that players work on the mistakes they made the day before. He had them playing what even before the DH rule came in was considered a little bit of “National League baseball,” featuring “surprise and subtlety.” Kaese approved. The “Williams trend is exciting,” he wrote. “As never before under Yawkey’s ownership, Williams has the Sox hit-and-running, bunt-and-running, hitting behind the runner, stealing and squeezing. The players have responded. Fancy Red Sox hitters giving themselves up by purposely hitting to right to advance a runner from second to third. Williams has restored the long-missing element of surprise to the attack.”

Self-deprecatingly, Williams laughed about one aspect of his conditioning program: “Maybe all we’ll end up with is the best volleyball team in Florida.”

It was Kaese’s column on March 27 that carried Williams’ prediction: “I honestly believe we’ll win more games than we lose.” It was one he uttered on several occasions. “I think we can beat five teams anyhow, and if that puts us in the first division, I guess that’s where we’ll be.” Kaese’s piece was optimistic, but concluded, “Williams is quick, determined, intelligent, but how he eventually makes out as a big league manager and as a volunteer for that hornet’s nest at Fenway Park probably will depend on how much iron he has in his makeup. I think he may have enough, but I’m not sure.”

Mike Andrews developed a bit of a bad back, pulling some muscles and re-aggravating an injury he’d apparently suffered lifting weights in the offseason; Williams put Reggie Smith in to play some games at second base. Smith started the regular season at second. Williams was more worried about his pitching than anything. The staff had a 3.92 ERA in 1966, but improved to 3.36 in 1967.

Near the end of the month, on the 28th, Williams picked George Scott as his first baseman. The team was to embark on a trip to the Virgin Islands for a couple of games and Williams was ready to go with a set lineup that included Boomer. With Andrews still out, Reggie Smith would play second with Jose Tartabull and George Thomas platooning in center. It was looking like Mike Ryan had the edge as the first-string catcher.

Yaz was in the midst of his best spring season yet, and March 29 saw him excel, hitting two homers, driving in six runs, and making what Will McDonough described as “three outstanding catches including the game-saver in the ninth inning.” The Red Sox took that one from the Cardinals at St. Petersburg, 10-9.

The next day, Boston got some excellent pitching and beat the Orioles 1-0, Lee Stange and Hank Fischer combining to give up just three singles. Stange retired the last 13 batters he faced. Tony C. was back in his first game since fracturing his shoulder, and doubled in the game’s lone run in the sixth. In the very same game, Yaz was hit on the hand by a Steve Barber fastball. Fortunately, x-rays were negative.

March 31 saw the Boston Red Sox playing baseball at St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands, before some 4,100 islanders who watched the game played on a cricket pitch that had been converted to a baseball field for the occasion. The Sox lost to Mel Stottlemyre of the Yankees, 3-1, as Stottlemyre threw seven full innings, giving up just two hits while striking out seven. He was facing the lineup Dick Williams had determined would be his Opening Day lineup. Lonborg gave up two runs in his seven innings, and took the loss.

The next day, the two teams squared off again, this time at St. Thomas, and this time the Red Sox won, 13-4, with Yaz (five RBIs), Rico, and Tartabull each hitting homers. Dennis Bennett was scheduled to start but was hit in the shin by a John Wyatt fastball and would have x-rays taken. That was the second pitch of the spring that Wyatt had unleashed and injured a teammate.

Playing second base didn’t faze Reggie Smith. Filling in for five games, he played errorless ball and hit .360 during the stretch. The experience served him in good stead; he played the first six games of the regular season at second. On April 2, Reggie doubled and homered. George Scott, playing both first base and also third base, homered as well. Rohr and Galen Cisco each gave up one run and the Red Sox beat the Mets, 8-2. The Sox had started slowly in spring training, but now had won nine of their last 14 games. What was the difference between this Red Sox team and the one he’d played on in ’63 and ’64? “The difference is that this is a ‘Team’,” Williams said. “I’m not one for past history, but I know when I was around here before it was an individual thing. I feel that one thing that has been overlooked about us this spring is the way that the players are playing for one another rather than themselves individually.”

Williams didn’t hesitate to get on a player if he felt it was called for. When the Pirates beat Boston 3-1 at Ft. Myers, Boston’s manager was livid. After Dennis Bennett had given up a triple that cost the Red Sox the lead, Williams gave him a “tongue-lashing” right on the mound. “I told him that it was a lousy pitch — and besides that, he should have been backing up third base on the play…My little boy could have handled that pitch.” Bennett had to agree it was a pretty poor pitch. One mistake in a meaningless exhibition game and Williams explodes? It wasn’t any big deal, was it? To Dick Williams, it was. Carl Yastrzemski, showing some team spirit, took some of the blame on himself for letting the ball get by him in the field.

The “other Williams” — Ted Williams — officially a VP at the time, kept a low profile in Winter Haven, but spoke out himself on at least one occasion. One day, he simply wasn’t there and Harold Kaese murmured Ted had a “relatively insignificant status” in camp; he noted that Ted didn’t hang around long. This Williams was back a few days later, though, criticizing Tony C. on April 5 for bunting in a two-out situation with Yaz on first in a scoreless game. He popped up, but the point — Ted said — was “we want the big hit and Tony’s capable of giving it to us. Instead he pops up to the pitcher. That’s evidence of poor thinking. That’s exactly how not to win games. Tony should know better.” Ted’s philosophy may have differed from that of the “wrong Williams,” but in this situation he might have been right.

In the final roster cut of spring training, Jerry Stephenson, Gary Waslewski, and reserve infielder Al Lehrer were sent to Toronto. That put the Red Sox one man under what was then the 28-player limit. They could have held onto at least one of them, but felt it was better to get them more regular work in the minors.

Though he’d been quoted along the same lines in Harold Kaese’s column a couple of weeks earlier, it was when he spoke to the press corps on April 7 that he made his famous prediction: “We’ll win more games than we lose this year.” McDonough wrote that, despite a strong spring season, most experts were picking the Sox for ninth place once again. After the final team meeting of the spring, Williams said he had told the players that they had given him 100% in spring training and if they kept it up during the regular season, they wouldn’t have any problems from him.

Ken Coleman later characterized spring training 1967, saying of Williams that he “ran more of a boot camp than a spring training, especially when compared to his predecessors. He insisted that every player be on time, put in a hard day’s work, not complain, and be there the next day for more. He wasn’t interested in discussion or debate with his players. There was one chief in camp, and it was Williams. Dick and his coaches installed a precise schedule for workouts: each player knew where he had to be and what he had to be doing at all times. When nothing formal was scheduled, a played was expected to run or participate in volleyball games.” Apparently, it worked. Coleman said, “Many grumbled, and a few made the mistake of doing it publicly; but no one actually challenged Williams. And so a funny thing happened on the way to the ball park — this unconnected bunch of young men developed into a spirited team who fighting character reflected that of their manager.”4

On April 9, the Globe published a story by Will McDonough evaluating each of the key Red Sox players. The story was accompanied by a chart showing how the Globe writers picked the race. Kaese, Clif Keane, and John Ahern picked Boston to finish sixth. McDonough and Ray Fitzgerald saw a seventh-place finish, and Roger Birtwell had them finishing eighth. Not one bought into the first-division optimism.

McDonough saw Yaz as in the best shape of his career, and noted that Tony C., hitting over .400 all spring could have the best season of his career, if he could “remain free from injury.” George Scott was the best-fielding first baseman in the league and was hitting about .300 in the springtime. Williams worried he’d backslide during the season, and “assigned coach Eddie Popowski to keep after Scott constantly.” With Andrews still unavailable, Reggie Smith was the second baseman. Though not as strong defensively, he would wield a good bat, as would Rico at short. Joe Foy was more of a worry, though he had potential: “Foy may be the best player on the team.” Tartabull and Thomas would platoon in center, Tartabull better all around but Thomas having the better arm. Mike Ryan still had first claim on the catcher’s slot, the strongest defensively among the trio of Boston backstops, but Russ Gibson or Bob Tillman would get called on if he was too anemic with the bat. Lonborg was first on a pitching staff still not seen as particularly strong. At least the staff seemed to be healthy. Brandon, Rohr, and Bennett were the initial rotation. Stange, Santiago, and Fischer weren’t far behind the quartet, and could be called in as necessary.

On April 9, the Red Sox lost the final spring training game to the Tigers, 4-3 in the 10th inning, but the Sox nevertheless won more than they lost during Grapefruit League play, by one game: they had a 14-13 record. Tony Conigliaro led the team in hitting with a .405 spring average. Mike Andrews was second at .395, and Scott third at an even .333. Reggie Smith and Jose Tartabull both hit over .300. Yaz hit just .257 but tied for the team lead with Petrocelli (.247) with five home runs each. Yaz led the team with 15 RBIs. Williams thought the Red Sox had the best outfield in the American League. The Red Sox were ready.

Clif Keane’s front page story on April 11 was headlined “Sox Open With Hope, High Praise.” The temperature at Fenway Park that day was 35 degrees, with winds gusting to 40 mph. The game was postponed due to cold. The Yankees won their game in Washington, though, and took first place. The second attempt found temperatures had risen to 46 degrees and the gusts had moderated to just 20 mph. The game went on. Some 8,324 fans braved the conditions and saw Boston beat Chicago, 5-4. Feature columnist Diane White wrote a front page story in the Globe, which bore the headline “Red Sox Win, Optimism Runs Rampant.” White cited a good omen: the “Lady in Red” was back. Though a dedicated fan of long tenure, Mrs. Carter S. Knight of Peabody had declined to come to Opening Day in 1965 or 1966 because she was “disgusted with their half-hearted performance.” But she was giving the new-look team a chance: “I like Dick Williams’ style of play. They really look better under the new leadership.”

So they did.

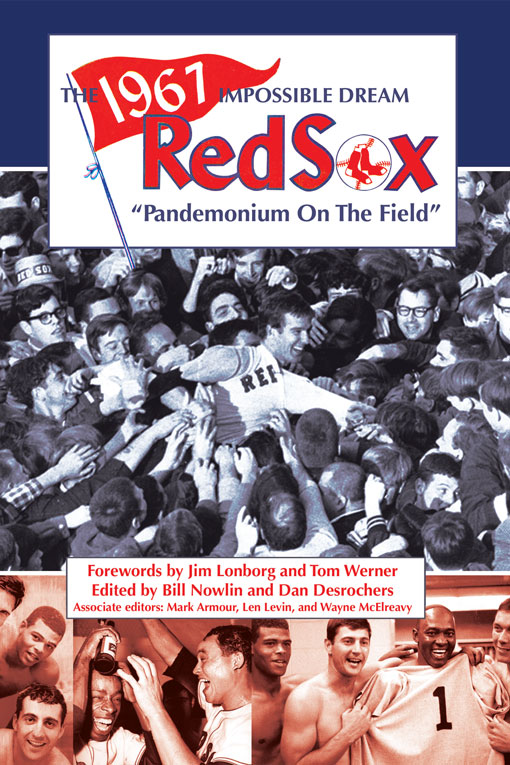

BILL NOWLIN was one of the first fans to the mound when Jim Lonborg induced the final out and the Red Sox won the 1967 pennant. He was elected as SABR’s Vice President in 2004 and re-elected for five more terms before stepping down in 2016, when he was elected as a Director. He is also the author of dozens of books on the Red Sox or Red Sox players, including “Ted Williams At War” and “Love That Dirty Water: The Standells and the Improbable Victory Anthem of the Boston Red Sox” (both from Rounder Books.) He has written Johnny Pesky’s biography (Mr. Red Sox) and co-edited a series of Red Sox “team books” written by numerous SABR authors that focus on different years when the Red Sox fielded exceptional teams, including: ‘”75: The Red Sox Team that Saved Baseball” (2005); “The 1967 Impossible Dream Red Sox” (2007); “When Boston Had The Babe: The 1918 Red Sox” (2008); and “Lefty, Double-X, and The Kid: The 1939 Red Sox, a Team in Transition” (2009). He is also co-founder of Rounder Records of Cambridge, Massachusetts. He’s traveled to more than 100 countries, but says there’s no place like Fenway Park.

Sources

All quotations taken from the Boston Globe, except as noted.

Notes

1 Henry McKenna, “Skipper of the Sox,” Official Souvenir Program of the 1967 World Series.

2 Ken Coleman and Dan Valenti, The Impossible Dream Remembered (Lexington, Massachusetts: The Stephen Greene Press, 1987), 22.

3 Ibid., 30.

4 Ibid., 10, 11.