Rupe’s Troops, No Más Monge, and Tempy Turns It Around: Part of the Padres Golden Era

This article was written by Brian Wood

This article was published in The National Pastime: Pacific Ghosts (San Diego, 2019)

The San Diego Padres had a miserable start to their existence. In their first 13 seasons, only once did they finish above .500, in 1978, when they finished 84–78. The second time they would accomplish this feat, their reward would be the 1984 World Series. It was part of the Padres first Golden Era, 1982–85, when they would run off four consecutive .500-plus campaigns and from May 1984 to May 1985 were the best team in the National League West.These are stories of three key ingredients in transforming the Padres from an also-ran to an elite major-league team.

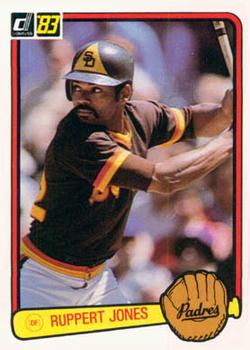

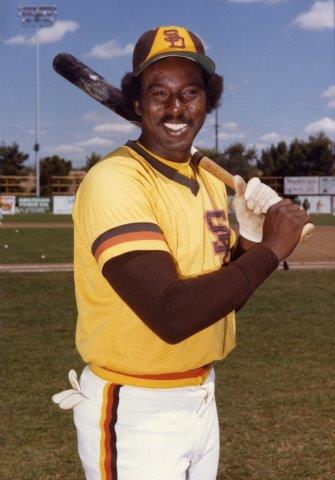

1982: Rupe’s Troops

“Rooooop! Rooooop!” In the long tradition of major leaguers with an “ooh” sound in their names (from B–o͞o-g Powell to M-o͞o-kie Betts) came Ruppert (R–o͞o’-pert) Jones.

“Rooooop! Rooooop!” In the long tradition of major leaguers with an “ooh” sound in their names (from B–o͞o-g Powell to M-o͞o-kie Betts) came Ruppert (R–o͞o’-pert) Jones.

Jones attended high school in Berkeley, California, playing in the same outfield with future big-leaguers Claudell Washington and Glenn Burke.1 Taken from the Kansas City Royals by the Seattle Mariners with the first pick in the 1976 expansion draft, Jones gained immediate popularity in the Emerald City with his spectacular play in center field.2 The adoring fans came to be known as “Roop’s Troops.” He was an All-Star in 1977, and in 1979, setting career highs in runs (109), hits (166), triples (9), RBIs (78), and stolen bases (33).

Jones ended up in San Diego in 1981, where he would anchor the Padres outfield for three seasons. After a horrific start, batting .185 in mid-May, Jones went on an 18-for-49 tear (.367), giving Padres fans a look at his potential. He finished the year at .250.

He started 1982 firing on all cylinders and was batting .356 on June 1. This, along with a team-record 11-game win streak in April, reignited the Rupe’s Troops craze (with the new spelling), with fans and teammates proudly wearing T-shirts bearing the slogan.3 At the end of warm-up tosses prior to each inning, Jones would throw the ball into the center-field stands (a practice that was not as commonplace as it is today), further endearing him to the fans. Coach Bobby Tolan remarked, “When it comes to working hard, Tim Flannery and Ruppert are numbers one and two.”4

He was selected as the Padres’ lone representative in the 1982 All-Star Game, where he knocked a pinch-hit triple off of Dennis Eckersley of the Boston Red Sox.

Two weeks later, Jones twisted his ankle and heel, causing him to miss nearly a month of the season.5 After returning, he was unable to regain his prior level of excellence. At the time of the injury, he had a slash line of .303/.399/.467. For the remainder of the season, he fell to .218/.286/.287 with no home runs.

His hitting woes would continue into 1983 (.233, 12 HR, 49 RBIs). His power would undergo a resurgence, but not with the Padres. H signed as a free agent with the Detroit Tigers where he slugged .516 and played on their 1984 World Series team against the Padres. He signed with the California Angels in 1985 and slugged .447 with 21 home runs.

Jones’s presence on the Padres added a stabilizing influence on a team that was trying to create a winning atmosphere.

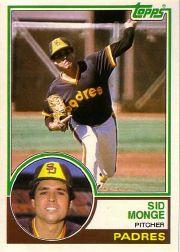

1983: “No Más Monge,” the Rise and Fall of a Padres Reliever

Isidro “Sid” Monge, born in Mexico and raised in California, hit his stride with the Cleveland Indians in the late 1970s, earning an All-Star slot in 1979 as he sported career bests in saves (19), ERA (2.40), and WAR (5.6). He was awarded Cleveland’s 1979 Good Guy Award, given to a player for his cooperation with the public and media.6 “Even during tough times, I have always had time to talk,” Monge said.7 But his performance dipped in 1981 and he was dispatched to Philadelphia.

Isidro “Sid” Monge, born in Mexico and raised in California, hit his stride with the Cleveland Indians in the late 1970s, earning an All-Star slot in 1979 as he sported career bests in saves (19), ERA (2.40), and WAR (5.6). He was awarded Cleveland’s 1979 Good Guy Award, given to a player for his cooperation with the public and media.6 “Even during tough times, I have always had time to talk,” Monge said.7 But his performance dipped in 1981 and he was dispatched to Philadelphia.

The Padres were hungry to bolster their bullpen and in May 1983 they acquired the veteran lefty from the Phillies. Monge had previously established a good relationship with both manager Dick Williams and pitching coach Norm Sherry, having played for both in the Angels organization in the early 1970s. Monge felt that both understood his need to be used frequently and in tight situations. “Sid is primarily a power pitcher, who also has a good slow curve,” Williams said upon Monge’s arrival on the West Coast.8

His start with the Padres was spectacular: He gave up no runs in his first 15.1 innings over 10 outings. His superb mound work continued over his next 21 outings (2.83 ERA) before he went into a short slump (14 runs allowed in 14 innings). That began on August 26 after a hard comebacker up the middle by Andre Dawson of the Chicago Cubs hit Monge in the head.9 He closed the season with a flurry, allowing just one run in his last 10-plus innings. Monge racked up seven saves and seven wins for the Pads with an ERA of 3.15 (ERA+ 113). “It makes a difference when you get to pitch when the game means something,” he said.10 The Padres ended with an 81–81 record for the second consecutive year.

Going into 1984, San Diego was picked to finish first in the National League West by the Gannett News Service and second by the Associated Press.11 Analysis provided by Bill James in his 1984 Baseball Abstract predicted, “The Padres are going to be one of the most exciting teams to watch in 1984. . . . They could be tough to beat.”12

Fireman Rich “Goose” Gossage had been picked up from the New York Yankees to anchor the bullpen, while Monge was expected to be the left-handed set-up man and occasional closer. San Diego got off to a great start, winning eight of nine.

The same could not be said for Monge. Seeing his first action in the third game of the season, he entered with no outs and a runner on first in the top of the ninth, the Padres leading the Cubs 2–1. He quickly retired the first two batters before giving up a double and an intentional walk to load the bases. Monge was not able to find the strike zone and walked Richie Hebner, plating the tying run. All was forgiven when San Diego’s Champ Summers banged an RBI double to win it 3–2. Monge got the win, not the save, and the Padres were off to a 3–0 start.

His next outing came two days later, also against Chicago, with the score knotted at three with one out and the bases loaded in the ninth inning. Chicago manager Jim Frey sent up pinch-hitter Keith Moreland. Once again, Monge could not find the plate and walked Moreland on four pitches, then Ron Cey on five to bring in two runs.13 Williams pulled Monge as the Padres faithful voiced their displeasure.14 After the game, Monge said, “I was all wound up and needed a strikeout. Consequently, I overthrew and couldn’t get the ball over the plate.”15 The Padres again showed their mettle, answering with two runs of their own in the bottom of the ninth to send the game into extra innings. Chicago put three across in the 10th to win the game and hand the Friars their first loss in five games. In two games, Monge had given up four walks in one inning pitched and allowed three inherited runners to score.

It would six days before Monge would be used again, this time in a mop-up role. The next day, he was brought in as a long-reliever in the third in a 3–3 game against the Atlanta Braves. He pitched three innings and allowed just one unearned run (on base via a walk, however). The Padres scored three times in the bottom of the third as they defeated Atlanta 6–4. Monge got his second win and San Diego climbed to 9–2, good for first place in the NL West by 3½ games over the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Monge appeared in three games, all losses, in a four-game series in Los Angeles, giving up five runs in four innings pitched, walking two, and allowing an inherited runner to score. The Dodgers pulled to within a game and a half of the Padres.

On May 4, Monge faced his nemesis, the Cubs, at Wrigley Field. With the game tied in the bottom of the ninth, a walk, error, sacrifice, and intentional walk loaded the bases and put the winning run on third. Once again, Frey used Moreland, who walked to force in the winning run. “He didn’t throw any of the pitches close,” Moreland said. “That one that was a called strike wasn’t even close.” Monge tried to make the best of it with some forced humor: “Anybody have any tips? I’ve never had anything like this happen to me before. I don’t have any sense of where the plate is. This is no fun at all. This team is battling back time and again, which is the sign of an excellent ballclub. I just want to be able to contribute.”

It was not just Monge. The entire Padres pitching staff was walking too many batters. Steve Dolan of the Los Angeles Times surmised, “Manager Dick Williams is on the verge of giving one of them [relievers] his walking papers. Right now, Sid Monge looms as the likely candidate.” Fred Mitchell of the Chicago Tribune called Monge “Mr. Wild-High-and-Wide.”16

Monge’s next appearance was nine days later at home against the Phillies, and again, walks did him in. In one-plus innings of work, he allowed three hits, two walks, and three runs. His next three outings appeared to be better, with no runs allowed. But digging deeper shows otherwise: Monge walked three and allowed two inherited runners to score. Williams obviously lost confidence in the southpaw. He had gaps of 15 and six days between his next appearances and was used only in long and middle relief.

On June 10, Monge was sold to the Tigers, joining former Padres teammate Jones. Monge became just the third player to have played for both World Series teams in the same season.17

The Padres maintained their pace in 1984 and finished 12 games ahead of the second-place Braves to advance to the postseason for the first time in club history.

Monge was gone but not forgotten by Padres fans. San Diego’s Old Mission Bay Athletic Club sponsors an annual July softball “Over-the-Line” tournament. The event features three-person softball teams playing in the sand courts. Sun, beer, and competition are all part of the package, as are inventive team names. One such name gave a shoutout to both boxer Roberto Duran most famous utterance and to Monge with the moniker “No Más Monge!”xviii

Although his 1984 season was a personal disappointment, his efforts in 1983 helped San Diego to a .500 season and his presence added to the culture of winning being established by the Padres, culminating in their advance to the World Series.

1984: Tempy Turns It Around

In December 1981, Padres general manager “Trader Jack” McKeon pulled off his second blockbuster trade with the St. Louis Cardinals in the space of a year. The first had been a 10-player deal that ended up with the Padres acquiring future catcher Terry Kennedy for future Hall of Fame reliever Rollie Fingers and catcher Gene Tenace. Now, McKeon dealt another future Hall of Famer, shortstop Ozzie Smith, and pitchers Steve Mura and Al Olmstead for outfielder Sixto Lezcano, reliever Luis DeLeon, and “troubled” shortstop Garry Templeton, the first switch-hitter to amass 100 hits from both sides of the plate in one season.19 The following year, the Cardinals won the World Series with the help of these two trades. In his 15 seasons in St. Louis, Smith would establish himself as an offensive threat in addition to his magical glove. However, Kennedy, Lezcano, DeLeon, and Templeton all contributed to the success of the 1982–85 Padres.

In December 1981, Padres general manager “Trader Jack” McKeon pulled off his second blockbuster trade with the St. Louis Cardinals in the space of a year. The first had been a 10-player deal that ended up with the Padres acquiring future catcher Terry Kennedy for future Hall of Fame reliever Rollie Fingers and catcher Gene Tenace. Now, McKeon dealt another future Hall of Famer, shortstop Ozzie Smith, and pitchers Steve Mura and Al Olmstead for outfielder Sixto Lezcano, reliever Luis DeLeon, and “troubled” shortstop Garry Templeton, the first switch-hitter to amass 100 hits from both sides of the plate in one season.19 The following year, the Cardinals won the World Series with the help of these two trades. In his 15 seasons in St. Louis, Smith would establish himself as an offensive threat in addition to his magical glove. However, Kennedy, Lezcano, DeLeon, and Templeton all contributed to the success of the 1982–85 Padres.

With a lifetime .305 batting average coming to San Diego, Templeton would bat a mediocre .255 over his first three seasons with the Padres. Smith had a lower batting average (.249) but his glove led him to three consecutive All-Star Games and Gold Gloves (8.3 dWar over those three seasons vs. 3.0 for Templeton). During that time frame, many fans felt as though the Padres had gotten the raw end of the deal.

The end of the 1984 season found the Padres atop of the NL West and facing the Cubs for the right to go to the World Series. It was not until Game Three of the League Championship Series that Templeton’s stock, like the Grinch’s heart, “grew three sizes that day.”20 Down two games to none by a combined score of 17–2, the Padres faced elimination in the best-of-five series. Before a record crowd of 58,346 abuzz with excitement at Jack Murphy Stadium, the Padres played in their first-ever home postseason game.

“The teams were introduced, and Templeton heard his name being called over the loudspeaker system as the shortstop and No. 8 batter in a nine-man lineup,” wrote Joseph Durso in the New York Times. “He ran onto the field, slapped hands with his teammates, then turned to the crowd, waved his cap and raised his fist in a gesture of defiance at the Cubs and the odds.”

Tempy’s gyrations became more pronounced as the crowd grew louder and louder. ”It surprised all of us,” said manager Williams, ”I’ve never seen him so emotional. Normally, he doesn’t talk much. He’s no pop-off or rah-rah guy. But, if I’m walking through a jungle, he’s the one I want by my side.”

”I was trying to get the fans to rally behind us,” Templeton said. ”But most of all I wanted to get my teammates going. I saw our guys just standing there, and I thought I’d do a little something to fire them up and get the adrenaline flowing. Somebody’s got to do it. It worked for the Cubs with the reaction of their fans, and it can work for us here.”

Templeton’s presence was felt from the get-go as he ended a Chicago threat in the first by making a spectacular leaping catch and roll on a Leon Durham line drive with a runner on second and two outs.21 In the second, the Cubs got on the scoreboard after a Moreland double (not a walk!) and a Cey single. Templeton stopped the rally with a diving two-out catch of Bob Dernier’s shot toward left field.22

Still trailing 1–0 in the bottom of the fifth, the Padres led off with singles by Kennedy and Kevin McReynolds. Up stepped Templeton. The crowd gave him a huge ovation (as they had in the third when he flied out to left field). This time he responded with a double to the left-center-field gap, knocking in two runs. He scored on an Alan Wiggins single to give the Padres a 3–1 lead.23 Behind the five-hit pitching of Ed Whitson and Gossage, San Diego prevailed 7–1.

After the game, Gossage said, “It was the loudest crowd I’ve ever heard anywhere,” a significant declaration from someone who had played in two World Series in Yankee Stadium (1978 and ’81).24

The New York Times wrote, “People were saying today that Templeton had made the key hit and the key defensive plays that helped the Padres win their first game of the National League playoff Thursday evening. And even the Cubs were conceding that the 28-year-old shortstop had fired his teammates and their fans into a frenzy that had enlivened and prolonged the playoff.”25

San Diego would win the next two games and advance to the World Series. Steve Garvey ended Game Four with a walk-off home run in the ninth to give the Padres a 7–5 victory. Templeton singled and scored the first run of the game. In the clincher, San Diego overcame a 3–0 deficit with two runs in the sixth and four in the seventh for a 6–3 win, with Templeton adding a single to the effort. In the Fall Classic, their first, the Padres would go down quickly to the Tigers, losing 4–1.

The 1984 postseason was the highlight of Templeton’s time with the Padres. He batted .333 with a .412 on-base average in the NLCS and he batted .316 in the World Series. McKeon called him the catalyst of the team, saying that defensively, “He turned everything he touched into an out.”

Templeton was a Silver Slugger Award winner in 1984 and an All-Star in 1985. From 1987 to ’91 he carried the title of captain, a testament to the respect of his coaches and teammates. In 2015, the Padres enshrined him in their Hall of Fame.26

Postface

The Padres peaked early in 1985 with a 25–15 record on May 26. But they would finish the season at 83–79, good enough for their fourth consecutive record above .500. It took 15 seasons for the Padres to reach the postseason for the first time. It would take another 12 to do it again, losing the NLDS in 1996, and then making it to the World Series in 1998, where they were swept by the Yankees. Williams, still the only Padres manager never to have a losing year, was let go before the 1986 season and would go on to manage the Seattle Mariners for parts of three seasons. GM McKeon continued with the Padres through 1990, acting as field manager for the final three years. In 2003, he became the oldest manager to win the World Series with the Florida Marlins.

With four consecutive .500 or better seasons highlighted by a trip to the World Series, 1982–85 was truly the Padres’ first Golden Era, with personalities to go along with it. The shouts of “Roop, Roop,” the ups and downs of Sid Monge on the mound, and Garry Templeton turning the tide for the Padres were major parts of that gilded age.

BRIAN P. WOOD (Woodie) is a longtime San Francisco Giants fan and resides in Pacific Grove, California, with his wife Terrise. They have three sons, Daniel, Jack, and Nathan and dog, Bochy. A retired US Navy Commander and F-14 Tomcat Naval Flight Officer, Woodie is a Research Associate on the faculty at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey specializing in Field Experimentation of new technologies before they are sent to military forces.

Additional Sources

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

Notes

1 Adam Ulrey, “Ruppert Jones,” SABR Bio-Project. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/12b9ab8b.

2 Ulrey.

3 Steve Dolan, “Swing Era Returns for Padres’ Ruppert Jones,” Los Angeles Times, July 29, 1983.

4 Dave Distel, “Padres’ Decision Not to Deal Jones Has Paid Off,” Los Angeles Times, June 4, 1982.

5 Dolan, “Swing Era Returns.”

6 Chris Cobbs, “Padres Cannot Play, Deal With Phillies Anyway,” Los Angeles Times, May 23, 1983.

7 Dolan, “Sid Monge,” Los Angeles Times, March 13, 1984.

8 Cobbs, “Padres Cannot Play.”

9 “Montefusco Sent to Yankees While Padres Lose Again,” Los Angeles Times, August 27, 1983.

10 Dolan, “Dravecky, McReynolds Team Up, 5–3,” Los Angeles Times, June 9, 1983.

11 “National League West Predictions,” Green Bay Press-Gazette, March 29, 1984.

12 Bill James, The Bill James Baseball Abstract 1984 (New York: Ballantine Books, 1984), 79 (thanks to Scott Merzbach).

13 Dolan, “First Loss,” Los Angeles Times, April 9, 1984.

14 Fred Mitchell, “Cubs Roll,” Chicago Tribune, April 9, 1984.

15 Dolan, “First Loss.”

16 Dolan, “Chicago Strolls Past the Padres, 7–6,” Los Angeles Times, May 5, 1984.

17 Others: The others were Jack Kramer with the Yankees and Giants in 1951 and Johnny Schmitz with the Yankees and Dodgers in 1952. Five additional players have since achieved this feat: Lonnie Smith (Cardinals-Royals, 1985), Jim Bruske (Yankees-Padres, 1998), Chris Ray (Rangers-Giants, 2010), Bengie Molina (Giants-Rangers, 2010), and Arthur Rhodes (Rangers-Cardinals, 2011). Bruske and Ray didn’t apear in the World Series. In addition, in 1901, Jimmy Burke played for both the AL and NL champions, the White Sox and Pirates.

18 “No más” were the words attributed to Duran during his 1980 bout against Sugar Ray Leonard. Whether the words were a figment of announcer Howard Cosell’s imagination or Duran actually said “no sigo” (“I’m not going further),” “no más” became part of the boxing and sports lexicon. Ray Monell, “Roberto Duran tells the real story behind the ‘No mas’ bout,” New York Daily News, August 25, 2016. https://www.nydailynews.com/latino/roberto-duran-tells-real-story-behind-no-mas-bou-article-1.2765921.

19 A number of Templeton’s actions had set off some Cardinals fans: He turned down an All-Star Game invitation in 1979 (where he would have played with both Ruppert Jones and Sid Monge) because he was not the starter; his fluid movement in the field caused some to label him a slacker; he had various contract disputes; and in late August 1981 he failed to run to first following a strikeout on a ball that bounced away from the catcher (he had a bad knee at the time). Templeton responded to the St. Louis boo birds with an obscene gesture, which was followed by increased booing and a second gesture. Manager Whitey Herzog called him in from the field and the two had to be pulled apart. Templeton would spend two weeks in a hospital due to depression prior to the trade to San Diego. The 10 years he played in San Diego were without controversy. Jeff Sanders, “A Padre for a decade, Garry Templeton made a home in San Diego,” San Diego Union-Tribune, January 30, 2018. https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/sports/padres/sd-sp-padres-garry-templeton-made-a-home-in-san-diego-20180130-story.html; Joseph Durso, “Templeton Spurs on Padres,” New York Times, October 6, 1984. https://www.nytimes.com/1984/10/06/sports/templeton-spurs-on-padres.html.

20 Dr. Seuss, How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (New York: Random House, 1957).

21 Durso, “Templeton Spurs on Padres.”

22 Bob Kravitz, “Templeton’s bat, glove ignite Padres’ fire,” San Diego Union, October 5, 1984.

23 Durso, “Templeton Spurs on Padres.”

24 Jay Johnson & Joe Hughes, “Full house beats 9 Cubs,” Chicago Evening Tribune, October 5, 1984.

25 Durso, “Templeton Spurs on Padres.”

26 Bill Center, “Templeton Was ‘Catalyst’ of Padres’ 1984 N.L. Champions,” FriarWire, March 17, 2017. https://padres.mlblogs.com/templeton-was-catalyst-of-padres-1984-n-l-champions-1653906dfcf8.