Philadelphia in the 1882 League Alliance

This article was written by Robert D. Warrington

This article was published in Fall 2019 Baseball Research Journal

Histories of the Philadelphia Phillies portray the club’s admission to the National League (NL) as a straightforward and swift process. Early in 1883, League president Abraham G. Mills informed former star player and old friend Alfred J. Reach that the Worcester franchise was moving to Philadelphia. Mills asked Reach — now a successful business entrepreneur in the city — if he’d like to own the club. “I’m in,” Reach told Mills, and the Philadelphia franchise was quickly organized to play during the 1883 season.1 A simple story; indeed, too simple. The facts tell a different tale.

Histories of the Philadelphia Phillies portray the club’s admission to the National League (NL) as a straightforward and swift process. Early in 1883, League president Abraham G. Mills informed former star player and old friend Alfred J. Reach that the Worcester franchise was moving to Philadelphia. Mills asked Reach — now a successful business entrepreneur in the city — if he’d like to own the club. “I’m in,” Reach told Mills, and the Philadelphia franchise was quickly organized to play during the 1883 season.1 A simple story; indeed, too simple. The facts tell a different tale.

Philadelphia’s journey to NL membership was complicated and protracted. The team’s participation in the 1882 League Alliance was a crucial step toward major-league status, and Reach’s enthusiasm for joining the league may not have been as unbridled as depicted by some authors. This article examines the club’s entry into the Alliance, its 1882 season, and how the transition from the Alliance to the NL unfolded. It also investigates the genesis of the team’s longstanding nickname “Phillies” and questions the accuracy of the oft-told tale of how it became associated with the franchise.

Al Reach Creates His Club

Initial indications that Reach was interested in owning a professional baseball club appeared in October 1881. An article in the New York Clipper stated that “two first-class clubs in Philadelphia are promised” for the 1882 campaign. In addition to the existing Athletics club, “H. B. Phillips will act as manager of the new club now being organized … Al Reach, the veteran Athletic player, is to act as treasurer of the new club.”2

Why Reach decided to return to professional baseball as an owner probably is attributable to several factors:3

- He missed being part of the game. As a former player, Reach longed to experience the excitement of a baseball season again; if not on the field, then in the front office.4

- Reach judged Philadelphia had a sufficient population to support two professional clubs as long as they fielded “first-class” teams.5

- He had the capital to finance a team. The sporting goods company Reach owned had made him wealthy.6

- Reach believed his club could be profitable.7 Reviving major league baseball in Philadelphia — where it had been absent since 1876 — would spark renewed interest in the game among the city’s citizens..

- He relished the opportunity to challenge the Athletics — a club for which he once played — as the city’s premier baseball club.8 The time had come to end that reign.9

No Room in the American Association

The timing of Reach’s reentry into professional baseball was heavily influenced by the co-founder of his club, Horace B. Phillips. Manager of the Athletics during most of the 1881 campaign when that club was part of the Eastern Championship Association (ECA), Phillips saw an opportunity in Philadelphia and other large cities that did not have major league baseball teams. Seizing the initiative, he became one of the architects of the American Association (AA), which formed after the 1881 season to challenge the NL’s monopoly on major league status.

In September 1881, while still managing the A’s, Phillips invited baseball representatives in six cities — Cincinnati, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, Louisville, and Brooklyn — to attend the inaugural meeting of the Association.10 These cities were selected because they were not, for a variety of reasons, members of the NL, and because they represented a larger population base than the eight teams comprising that league.11

Phillips intended to have his Athletics club represent Philadelphia in the new organization. But fate intervened, and he was released as team manager in early October.12 If the A’s were going to join the Association, it would not be with Phillips at the helm. Undaunted, he joined with Reach later that month to organize a second professional club in the city that would petition for admission to the AA.13

The Association’s initial organizational meeting was held in Cincinnati on November 2, 1881. Reach and Phillips attended the meeting at which Reach announced he had “collected a large sum of money for the new club and promised that a first-class team would be placed in the field.”14 But the team’s membership posed problems for the Association. Establishing franchises in Philadelphia and New York — neither city was represented in the league — was essential to the organization’s challenge to the NL’s major league baseball monopoly. Its leaders, however, wanted to enroll one club from each city, not two, and the Athletics had also applied to join the Association.15

As noted, the Athletics had been the lead name in Philadelphia baseball since the 1860s. As John Shiffert has written in his study of the city’s early baseball period:

Although no less (sic) than six organizations would bear this name between 1860 and 1901, including a series of independent professional teams in the late 1870s and early 1880s and a minor league team in the 1890s, there should be no doubt that the best in baseball in Philadelphia in the nineteenth century usually meant Athletic baseball.16

For a new baseball organization determined to prove its legitimacy as a major-league alternative to the NL, the choice of which franchise to select was easy for Association leaders. Phillips was pressured to combine his bid with the Athletics’ application so the two groups would enter the AA as a single franchise.17 But the amalgamation was purely a face-saving device for Phillips and Reach. Ownership and management of the Athletics had already been established under William Sharsig, Charles Mason, and Chick Fulmer.18 They had no interest in sharing leadership of the club with Reach and Phillips, especially the latter whom they had fired as team manager the previous month. As the AA organized for the 1882 season, Phillips, Reach and their ballclub found themselves excluded from the organization.19 As one history notes:

And the City of Brotherly Love had split into two factions again with the Athletics the winner, leaving Horace Phillips, one of the prime movers to create a new major league, for the moment aced out of a spot in it.20

Undesirous of operating as an independent amateur club, Phillips and Reach needed to affiliate with another professional baseball organization, and the only one available was the National League. Yet, seemingly insurmountable problems existed with that union as well.

A Circuitous Approach to NL Membership

The formation of the AA was a nightmare scenario for NL owners, who strived to maintain the league’s monopoly on major-league status. Owners could hope the Association would fail, as had other upstart organizations seeking to be recognized as major leagues. But they also understood the disadvantages of having within its ranks teams from cities with smaller populations — Troy and Worcester — and were not about to cede the cities with the greatest populations — Philadelphia and New York — to the AA.21 Clubs representing those metropolitan areas had been expelled from the League after the 1876 season when they refused to make their final western road trips believing they would lose money because they were out of pennant contention.22 An embargo on Philadelphia- and New York-based teams remained in effect.23

In a conversation with a newspaper reporter during the summer of 1881, League President William A. Hulbert explained his unwillingness to remove smaller teams from the NL to make room for clubs from larger cities. The conversation was prompted by a request from the Metropolitans of New York for admission to the league. The reporter wrote:

President Hulbert has answered the application (from the Metropolitans) in a non-committal manner, saying that he will thoroughly investigate the matter. The chances the Metropolitans have for admission into the League if Hulbert alone is to be consulted may be deemed rather slim, judging from what he recently informed a Chicago reporter. He said that he would never consent to any course toward any member of the body, no matter how weak, looking for securing its withdrawal in order to let in any other organization, however strong, or however much it might promise in the way of patronage of the game. The present members, who had helped to build up and make the League the success that it is has rights in it, and as long as they did not see fit to withdraw from it, he would vote to retain them to the exclusion of all others. Whether all the eight would elect to remain next year he did not know. If one of them, or two of them, should drop out, there would be so many places to be filled from the most available materials at hand; if not, he did see any chance for outside applicants.24

The Metropolitans’ application was not approved when NL owners met on December 7, 1881, in part because none of the clubs that composed the NL in 1881 had chosen to leave the league, intending instead to continue as members during the 1882 season.25 The league also remained bound by Hulbert’s prejudices against New York and Philadelphia, whose ouster from the NL he had orchestrated in 1876.26

But Hulbert had become seriously ill by the time of the owners meeting in December. Despite his protest that he could no longer continue as league president, Hulbert was reelected to the position.27 Owners realized retaining him as president would maintain the embargo, but Hulbert was absent from the December meeting because of his illness. This gave NL owners an opportunity to counter the threat posed by the AA’s emergence. If they needed a reminder of the magnitude of that menace, it was provided by the New York Clipper:

The six cities represented in the American Association contain over two million inhabitants, while the eight cities of the rival professional association foot up but little more than half that number.28

The owners chose an alternative structure to confront the twin challenges of rectifying the sizable population imbalance favoring cities represented in the AA while sustaining the embargo against Philadelphia and New York. This approach would keep clubs based there out of the AA, formally link them to the NL, allow games between teams in those cities and the league to be played during 1882, and position Philadelphia and New York to join the NL in 1883. That was the League Alliance.

The League Alliance

The League Alliance was initially established by the NL in 1877 as a means to extend its control over independent teams across the country. It served several purposes for the league and its members:

- Discouraging contract-jumping and escalating salaries by forbidding clubs from luring players away from alliance teams with offers of more money.

- Allowing games against alliance members to be scheduled on off-days. Doing so would expose baseball to wider audiences and provide potentially lucrative paydays for clubs.

- Creating opportunities to assess alliance clubs and their players for possible future recruitment into the league.

- Dissuading teams that joined the alliance from banding together to organize a second major league that would compete with the NL.29

There were minimal requirements for admittance into the League Alliance. Clubs had to agree to play by NL rules and abide by decisions of the league regarding disputes. The league secretary was informed of players under contract to alliance teams so NL clubs would not attempt to sign them.30

Estimates of the size and composition of the 1877 alliance vary depending on the source.31 Twenty-eight clubs were listed as members at various times during 1877, but many disbanded due to insolvency; only five played as many as 30 games against other alliance teams. The organization itself, while continuing to exist formally on paper, became largely dormant after 1877.32

At the December 1881 meeting, NL owners revised the league’s constitution to resuscitate the League Alliance, make it more sustainable as a business operation, and smooth the way for teams from New York and Philadelphia to gain membership. The most important changes were:

- Any club could join by signing an agreement and paying $25.

- Only one club could join from any city.

- No NL clubs could play games against non-league clubs in any city in which an alliance team was located.

- There would be an alliance championship series.33

John B. Day, president of the New York club — formally named the Metropolitans of New York–attended the December meeting as a non-voting member and accepted the offer to join the alliance.34 In addition, a letter from Reach, in which he agreed to have his Philadelphia club become a member of the Alliance, was read to the assemblage.35 NL owners approved the entry of both into the organization and limited membership to just those clubs.36 This was done primarily for four reasons:

- It maximized the number of games New York and Philadelphia would play against league teams and each other in anticipation of the cities’ admittance to the NL in 1883.

- Games held in the two cities with the largest populations would almost certainly draw the greatest number of fans and prove the most lucrative.

- Having NL clubs visit New York and Philadelphia would whet the appetite of fans eager to see the League return to their cities and play games on a regular basis.

- An alliance team in Philadelphia would deny the Athletics exclusive major league status in the city, and discourage support for the association from taking root there by providing a different professional club to follow.37

A newspaper report on Philadelphia’s alliance membership noted the franchise had been snubbed by the AA, and identified the great challenge it faced in actually fielding a team:

The Philadelphia Club under the management of H.B. Phillips and Al Reach has been admitted to the League Alliance. This is the same club that the American Association declined admitting, and as yet exists only on paper.38

Finding a Home

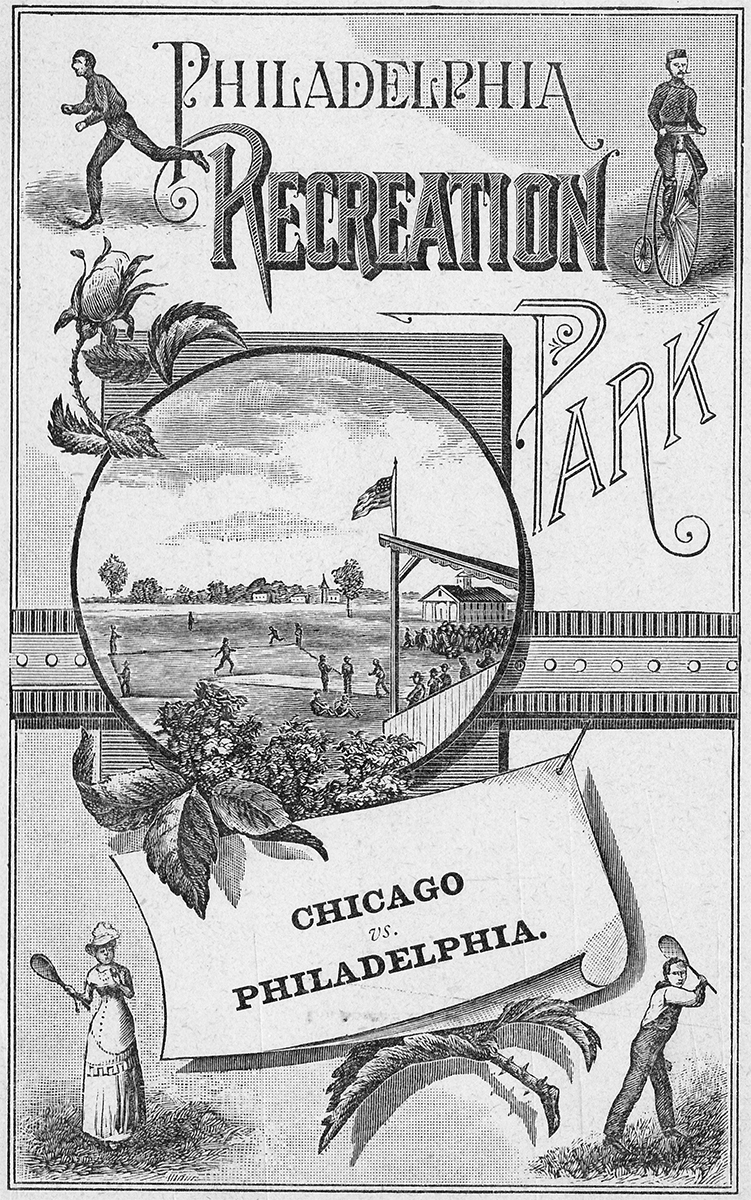

Among the most pressing needs facing Reach in operating his team was finding a ballpark to call home. Fortunately, a location existed that had hosted baseball games since as early as 1860. Recreation Park, positioned at the intersection of 24th Street and Ridge Avenue in what was then an outer portion of Philadelphia, had been the site of home games for multiple amateur clubs and the Centennials of the 1875 National Association.39 More recently, the Philadelphias ballclub of the 1881 ECA had called it home.40

Even before being accepted into the alliance, Reach and Phillips had focused on Recreation Park as the site for their ballclub’s home games.41 Reach sought to secure the facility, but discovered it had been leased for other purposes in 1883.42 His search broadened, including negotiating for use of the circus lot at Broad and Federal Streets.43 Eventually, however, Recreation Park became available, and Reach immediately set about improving the grounds and grandstand, which had fallen into disrepair.44 A contemporary newspaper account of the upgrades provides an excellent depiction of the ballpark at the start of its tenure as home to Reach’s team:

The now handsome grounds of the Philadelphia Club located at Twenty-Fourth Street and Ridge Avenue present a striking contrast to the old rookery which existed there a couple of months ago … The changes effected involve the erection of a substantial fence, and also of a grandstand and four rows of free seats. The main stand has patent perforated folding numbered chairs. In the rear of these chairs are several handsome private boxes, capable of holding four to eight persons. The wings will be seated with regular chairs, the entire stand accommodating fully 1,500 persons. Along the left and right field fences seats with foot-rests will be provided sufficient for 2,000 people. The field has been plowed up, sodded and rolled, and is in splendid condition for ball playing … At the sides of the grandstand, dressing rooms for the players and offices for the managers have been erected. On top of the grandstand a handsome reporters’ stand has been placed.45

The Roster

With their club admitted to the League Alliance and their ballpark being readied for the upcoming season, Reach and Phillips had to move quickly to assemble a roster.46 If their team did not play top-flight baseball, fans would desert it, especially given the alternative to watch the Athletics play their games at Oakdale Park.47

Unexpectedly, finding a new manager for the club became part of this challenge. In early January 1882, Phillips resigned as manager and “severed all official connection with the Philadelphia Baseball Club.” This decision and its timing appear odd given the efforts Phillips had put into forming the club. According to a newspaper report on his decision:

(Phillips) intends hereafter to devote his entire and strict attention to the superintendency of lacrosse, football, lawn-tennis, polo, bicycling and other kindred sports at Twenty-Fourth Street and Ridge Avenue, Philadelphia.48

With Phillips’ departure, operation of the Philadelphia club came under the sole purview of Reach. It was apparent, however, he did not want to include field manager among his duties. His tenure in the role was characterized as “temporary” until a new manager could be found.49 By Opening Day in early April, John Manning was performing as the team’s player-manager.50 Phillips returned soon thereafter as field manager, but he would resign the role a second time before the season had concluded (see below).

Reach assembled a group of players with considerable professional baseball experience, despite the limited time. Moreover, with the notable exception of catcher, the position players remained for the most part in their roles throughout the season, a remarkable achievement for a newly formed club.

A review of the lineups the Philadelphia club fielded in games during 1882 shows the seven position players comprising the regular starting lineup in June still were part of it in October.51 A review of their baseball careers reveals the majority had prior NL experience before joining Reach’s team:52

- John “Pop” Corkhill, 1B53: No prior experience

- Tim Manning, 2B: Providence, 1882

- Arlie Latham, 3B: Buffalo, 1880

- William McClellan, SS: Chicago, 1878; Providence, 1881

- Mike Moynahan, LF: Buffalo, 1880; Detroit, 1881; Cleveland, 1881

- Fred Lewis, CF: Boston, 1881

- John Manning, RF: Boston, 1876, 1878; Cincinnati, 1877, 1880; Buffalo, 1881

Three of these players — McClellan, Lewis, and John Manning — would go on to play for the Philadelphia Club when it joined the NL in 1883, while Moynahan — would sign with the Athletics in 1883. The others would also continue their careers in professional baseball after 1882 with various NL and AA clubs.54

The position that proved most vexing for Reach to fill was catcher. The club experimented with nine different players at the position during the season, all of whom displayed various shortcomings. Joe Straub was the regular catcher during the first months of the season, but the team’s dissatisfaction with him was evident in its periodic audition of other players at the position.55 None of the potential replacements lasted very long, and the club eventually dismissed Straub himself because, according to one newspaper report, of his “inability to throw.”56

The peripatetic Phillips furnished a partial, short-term remedy. Having resigned his position as manager before the season started, Phillips did so again in July 1882, announcing he would organize a team to represent Indianapolis in the AA for the 1883 season.57

William Barnie, who had been managing the independentAtlantics of Brooklyn club, was hired to manage the Philadelphia club after Phillips resigned, a position Barnie would hold for the rest of the season.58 Barnie also happened to be an accomplished catcher, having played for teams in the National Association.59 When the club finally tired of Straub’s erratic throwing and released him, Barnie occasionally stepped in as catcher. He wanted to manage, not catch, however, and the club continued to audition catchers during games in September and October. None proved to be the answer; Reach’s team never found a long-term solution to its catching conundrum during the season.60

There were eight players on the team who appeared in almost 67 percent of Philadelphia’s games in 1882. Only one player, John Manning, appeared in every game.61 The roster fluctuated despite the stability these players provided to the lineup throughout the season. Reach, Phillips, and Barnie had to contend with player turnover while maintaining the team’s cohesion and improving its performance on the field.62 Players who appeared briefly for the club and then disappeared included infielder Frank Fennelly and outfielder Elmer Foster.63

Other players, such as Joe Battin and Frank Gardner, stayed longer with the Philadelphias but were still gone before the season ended. Released by the club in June, Battin signed to play with the independent Atlantics. After a few weeks with that team, Battin became something of a nomad. He umpired some games in the AA, but also played for various independent clubs during the rest of the season.64 Gardner played outfield and occasionally pitched for the Philadelphias during the first part of the season, but suffered an ignoble end with the team. He was suspended in early August for what was termed, “indifferent play.” Another account of the incident attributed Gardner’s suspension to “alleged dissipation.”65

Philadelphia’s pitching staff in 1882 was astonishingly constant because two men started over 86 percent of the games. The first incredible iron man in the box was Jack Neagle.66 He started 68 games, 49 percent of the total the team played that year.67 As amazing, he finished all but two games he started.68 Neagle’s record at the end of the season was 23 wins, 42 losses, and three ties.69 Hardly a commendable won-lost total, but a remarkable feat of endurance in terms of a single-season load for one pitcher.70

Neagle was out for ten days in May after being injured in a game, which undoubtedly cost him two or three starts.71 Moreover, when not hurling the ball, Neagle could be found patrolling the outfield in games, mostly in right field, but occasionally in left.72

That Neagle was a prized pitcher — as much for his endurance as his skill — was evident in the fact the Eclipse club tried to sign him for the 1883 season before the 1882 season concluded. The first report that talks were underway appeared in August, but they ultimately proved unfruitful. According to a newspaper article, “It is said that Neagle wanted $100 advance money, and that negotiations dropped right there.”73 The pitcher opened 1883 with Philadelphia, but shifted to Baltimore and then Allegheny — both in the AA — before the season concluded.74

The other iron man pitcher was Hardie Henderson. He had no professional baseball experience before 1882, but proved almost as durable as Neagle and ended the season with a winning record.75 Henderson started 52 games for Philadelphia in 1882, 37 percent of the games the team played that year. By the end of the season, he compiled a record of 28 wins, 21 losses, and three ties.76 With the exception of one game, furthermore, he finished them all.77 Like Neagle, Henderson could be found playing the outfield, mostly right field, in some games when he wasn’t in the box.78

Henderson joined Neagle in staying with Philadelphia when the team transitioned to the NL in 1883, but only for a single game. In it, he gave up 24 runs over nine innings and was gone from the roster. Henderson migrated to the Baltimore club of the AA later in the season and lost 105 games with that team from 1883-1886. He concluded his big-league career by pitching for the AA’s Brooklyns in 1887 and the NL’s Pittsburgh club in 1888.79

A few other pitchers made cameo appearances for Philadelphia in 1882. One with the last name of “Buffington” (sic) started two games early in the season.80 Philadelphia played its second game on the schedule on April 11, and he was trotted out against the NL’s Providence Grays, a formidable team that had finished in second place in 1881. Offering up a rookie pitcher against such a tough opponent didn’t turn out well:

The home team presented Buffington in the pitcher’s position, and he proved to be the weakest point, his wild delivery materially assisting the boys from Providence in running up their score … The experiment of placing such an inexperienced man as Buffington in the pitcher’s position against such a nine as Providence will not bear repetition.81

Suffering a 19-6 drubbing in that contest, the team remedied the situation by assigning Buffington to make his second start against a local amateur club, Young America, on April 22 at Recreation Park. He rose to the occasion by throwing the first no-hitter in the Philadelphia club’s history. One member of the opposing team reached first base on an error, and two others received free passes on walks.82

Norm Baker was another rookie pitcher who had a two-game stint with Philadelphia. He started consecutive games on September 6 and 7, competing against amateur teams. Philadelphia won both games by the scores of 13-3 and 5-2, respectively.83 Baker did not return to Philadelphia the next year, but instead, played for Allegheny in the AA. He spent the rest of his brief professional career in the association, pitching for Louisville in 1885 and Baltimore in 1890.84

The 1882 Season

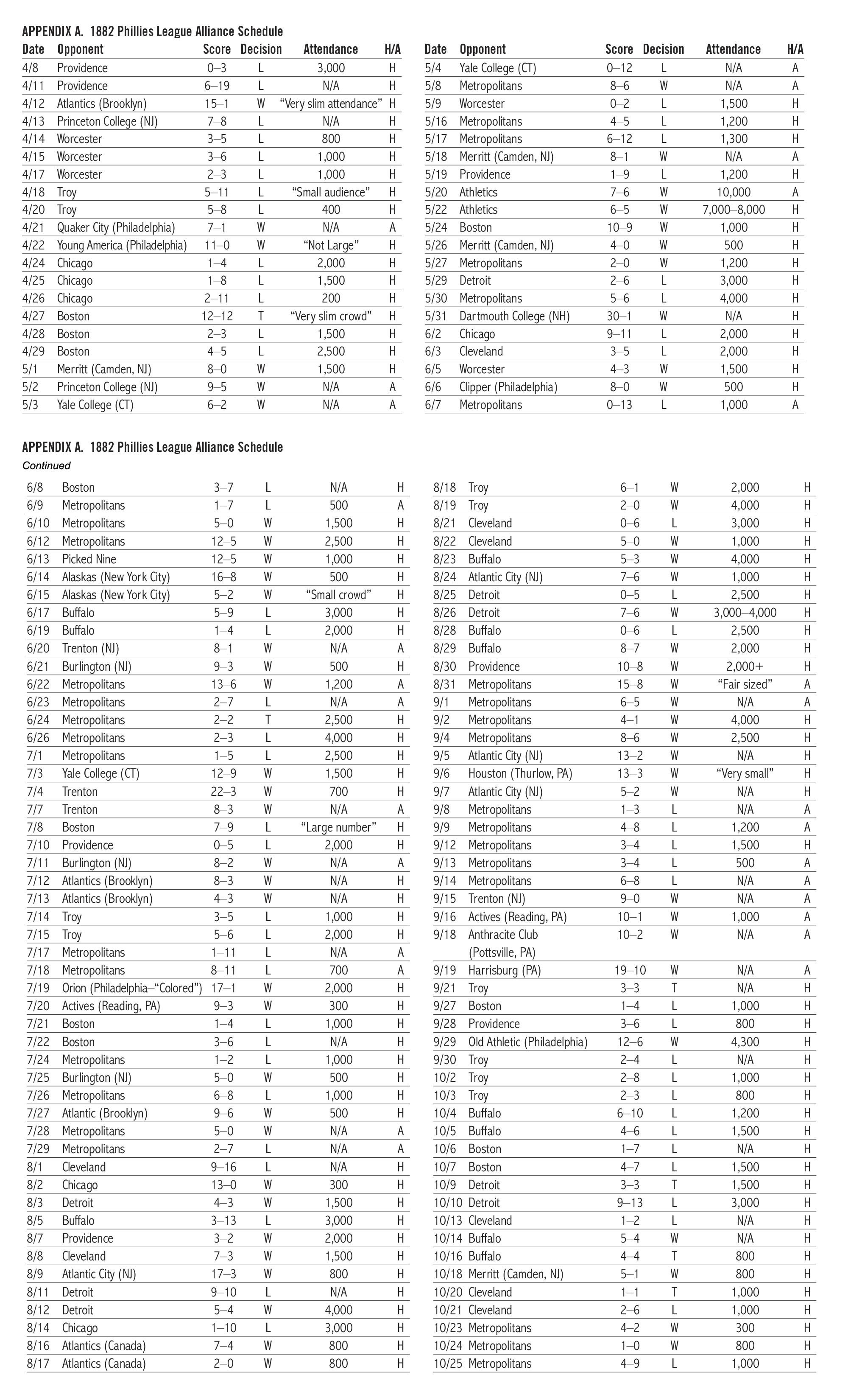

Philadelphia’s opponents during the 1882 season can be divided into three groups: the League Alliance Championship Series against the Metropolitans; NL and AA teams; and amateur clubs. Research done for this paper unveiled 139 games played by the Philadelphias that year. Overall, the team finished the season with a 67-66-6 record. Appendix A below lists the dates, opponents, final scores, decisions, attendance, and home/away venue for the games.85

League Alliance Championship Series

When the Metropolitan and Philadelphia clubs joined the League Alliance in December 1881, a provision was enacted that the two clubs would play a championship series,86 which would comprise 24 games.87 New York demonstrated its superiority, as the Metropolitans won their thirteenth game of the series on July 26, and claimed the League Alliance Championship.88 At that point, the Philadelphias had gained only five wins with one game tied. The games were mostly competitive, however, and drew sizable crowds at the Polo Grounds and Recreation Park, much to the delight of club owners.

One game of the series is exceptional because it illustrates vividly how much baseball has evolved — at least in one important regard — since 1882. Played at Recreation Park on May 17, the Metropolitans won 12-6. But what caught the attention of a sportswriter who reported the results was the number of balls used during the game:

That the contest was no ordinary one is proved by the fact that it took three balls to finish it. The first ball Corkhill hit foul over the fence, and it was rendered useless by being run over by a Ridge Avenue (trolley) car. The second the same player hit foul through a (trolley) window, and cut the covering.89

Although estimates vary, a generally accepted, frequently cited figure is that eight to ten dozen baseballs are used on average in a nine-inning baseball game now.90

With the League Alliance championship decided — despite five games remaining between Philadelphia and the Metropolitans — and almost half the baseball season still to play, a dilemma arose of how to sustain fan interest in the rivalry.91 To the rescue came a Philadelphia “gentleman who admires the sport.” He offered as a prize “a valuable silver punch bowl” to the winner of a new 12-game series between the Metropolitans and Philadelphia.92 Both clubs accepted and revised their schedules to allow for the extra games. The battle for the trophy began on August 31.93

The new series started auspiciously for Philadelphia, winning the first four games. But the Mets stormed back to win five in a row and take a one-game lead in the race for the punch bowl. Reach’s team tied the series by winning the tenth game in what was proving to be a very exciting competition. (See Appendix A below for the dates and scores of these games.) The outcome of the 11th game, however, was mired in controversy that marred the series’ conclusion.

The contest was played in Philadelphia on October 24. In what turned out to be a regrettable decision, Reach was selected to umpire the match. At the end of the sixth inning, the Philadelphias led 1-0 and claimed darkness had made the ball almost impossible to see. The Metropolitans, however, insisted on continuing play, and scored two runs in the top of the seventh inning to take the lead. Philadelphia had two outs in the bottom of seventh when Reach suddenly called the game on account of darkness. With his decision, the score reverted back to the last completed inning, and Philadelphia won the game 1-0, taking a 6-5 lead in the series. New York players howled in anger at what they regarded as Reach’s biased decision to keep his team from losing the game.94

The Metropolitans were in a foul mood when they took the field at Recreation Park on October 25 to play the final game of the series, believing they had been cheated the day before. According to one newspaper account of the contest, “The ‘Mets’ disputed every decision made by the umpire (Charles Fulmer) that was not in their favor, and in return, were hooted and jeered by the crowd.” The visitors won the game 9-4, thereby tying the series again 6-6.95

Reach offered what were described as “extra inducements” to the Mets to play a tie-breaking game on October 26, but they refused to stay over “on account of dissatisfaction at Reach’s action in calling the game on October 24.” 96 Thus, the New York-Philadelphia rivalry ended indecisively. While the series served its purpose in attracting good-sized crowds, the trophy went unclaimed.

Games Against National League and American Association Clubs

National League. It was up to Philadelphia and the Metropolitans to schedule their games against NL and AA opponents during the latter’s off-days. Financially, both teams had every incentive to maximize the number of games against professional competition because they would draw the largest crowds. Reach wasted no time trying to arrange matches.

At the March 7, 1882, NL owners meeting in Rochester, New York, Reach attended as a non-voting delegate representing his Philadelphia club, as did John B. Day for the Metropolitans. The 1882 NL schedule was approved at the meeting, and with its adoption, open dates were identified when NL teams would be available to play alliance clubs. Despite his best efforts, Reach secured only one date — a game against the Detroit Wolverines in Philadelphia on May 9.97

Undaunted, Reach continued his efforts and a month later had scheduled 30 games involving all NL clubs except Worcester.98 More games would be added as time passed, including against Worcester, and by the time the season ended, Philadelphia had played 65 games against NL opposition.99

The Philadelphias played all of their games against NL clubs at home, contributing significantly to a major imbalance in the number of home versus away games Reach’s club played in 1882. At season’s end, the final tally was 111 home games and 28 games on the road.100 (See Appendix A below)

NL owners had compelling reasons to allow Reach’s team to host all the games their clubs played against Philadelphia:

- They were eager to discover if enough fans would go to games throughout the season to warrant, from a financial perspective, adding the city to the league’s ranks. This was especially important given the presence of another major-league franchise in Philadelphia and the NL’s goal of adding “big market” clubs to its structure while shedding “small market” teams.

- Games in Philadelphia would likely draw bigger crowds than if the Philadelphias traveled to NL ballparks to play. Fans in those cities wanted to see their teams play major-league caliber talent, not newly formed, adjunct alliance clubs of lesser ability.

- Limiting travel expenses for Philadelphia would alleviate costs associated with operating the franchise; in particular, during its inaugural season when the club was still organizing and establishing its financial foundation.

In addition to permitting their teams to be the visitors in all games against Philadelphia and the Metropolitans, NL owners pledged not to play any other clubs located in or near those cities.101 Despite these generous terms, the owners also enacted provisions governing compensation to ensure they would not lose money in doing so. When NL clubs played each other, the home team was obliged to guarantee the visiting club $100 in compensation; if money received in gate receipts exceeded $200, then the visiting club would receive half of that amount.102 The same arrangement would apply in games hosted by alliance clubs. Moreover, if an NL team traveled to a League Alliance city and the game was postponed due to inclement weather, the visiting club would still be guaranteed a $50 payment.103 Although Reach and Day pleaded for more lenient treatment at the March League meeting, given their clubs were not full members of the NL, they were rebuffed and forced to accept the terms.104 The potentially adverse consequences were noted in a newspaper article that opined, “The Philadelphias very unwisely have submitted to the League’s demands, and consequently are in danger of being financially swamped.”105

Given the NL’s determination to run a “clean” sport, Philadelphia and the Metropolitans also were required to take steps to prohibit gambling at their ballparks — a scourge that had tainted professional baseball’s reputation for honest games in the past. The Philadelphias announced no open betting would be allowed at Recreation Park during the season, nor would the club permit telegraph wires to be connected from the grounds to city pool rooms where off-site betting on sporting events was concentrated. This was intended to thwart game updates from being communicated almost instantly from the ballpark to the gambling dens.106

A concession Philadelphia and the Metropolitans were able to obtain from NL owners was to charge a 25-cent admission fee for their games, half the NL minimum of 50 cents.107 Since neither club was actually in the NL, the reasoning was that people would be less willing to pay the league price to attend games. The arrangement worked out well for the NL and Philadelphia. In a revealing comparison of gate receipts for games against other league clubs versus those for games in Philadelphia, Detroit manager Frank Bancroft offered the following figures:

On the Detroits’ Eastern trip, recently closed, their share at Worcester for three games, at 50¢ admission, was $112; at Troy three games, $196; at Providence, three games, $496; at Boston, three games, $481; a total of $1,258 Against this, to prove that more money could be made at 25¢ admission, Bancroft gives his share of five games with the Philadelphia Club as follows: First game, $105; second, $217; third, $311; fourth, $223; fifth, $500; a total of $1,356, beating the League $98, with seven games to spare.108

Though enjoying home field advantage in every game against NL clubs, Reach’s team compiled a woeful 15-45-5 record in those contests.109 Collectively, the outcomes confirmed Philadelphia would have a long way to go to become competitive after joining the NL. Even with all the losing, however, robust crowds filled Recreation Park to watch their home team take on league opponents. Rarely did fewer than 1,000 fans sit in the stands, and attendance often exceeded that number.110 (See Appendix A below.) For this reason, the club’s won-loss record was not the most important measure of success. The season demonstrated Philadelphia could support an NL franchise; that was the most significant and enduring outcome of the games Reach’s team played against league clubs in 1882.

American Association

Reach longed to play the Athletics more than any other club. Pride played a role in his outlook; Reach wanted to dethrone the A’s as the city’s preeminent baseball club. He also needed to demonstrate to Philadelphia fans that his club could compete successfully at the professional level, and was not a second-class organization. In addition, dollar signs swirled in Reach’s mind when he envisioned spectators pouring into Recreation Park to watch games against his team’s intra-city rivals.

The evidence for such optimism was considerable as newspaper coverage stoked the city’s interest in the upcoming series:

The chief topic in baseball circles in Philadelphia, Pa., is the inaugural contest between the Athletic and Philadelphia Clubs for the local championship … The attendance, it is estimated, will be about the largest ever chronicled in the annals of baseball in the Quaker City.111

The only hitch in arranging the first game was the location. Both clubs wanted it at their home ballpark, believing the inaugural game would draw the largest crowd of the series. Moreover, instead of dividing gate receipts evenly, the Athletics and Philadelphias wanted the entire game receipts from games at their ballparks.112 It was eventually decided the A’s would host the first contest — not a surprise given the franchise’s predominant stature in the city — and the Philadelphias would be the home team for the second game, which would follow two days later.

The initial game at Oakdale Park on May 20 attracted an estimated 10,000 fans — the largest crowd to witness the Philadelphias play in 1882.113 The closely contested affair was followed with “almost breathless interest” by spectators who saw the visitors eke out a 7-6 victory by scoring a run in the ninth inning.114

The crowd that attended the second game played on May 22 at Recreation Park — while somewhat smaller in size — were treated to another tense match:

Never was there a more exciting game of baseball played than that yesterday between the Athletics and Philadelphia Clubs, which was won by the latter after ten innings had been played by a score of 6 to 5. Between seven and eight thousand people paid the admission fee to Recreation Park, while fully a thousand more witnessed the contest from the windows and roofs of surrounding houses. All the railways leading to Twenty-Fourth Street and Columbia Avenue ran loaded cars as early as two o’clock, and by three o’clock all the available seating capacity was crowded, while the people were still coming in droves. A portion of the right and left field was roped off to make room for the crowd, and when the game commenced there was not room for even one more.115

Amid the euphoria generated by the first two games, a third game was scheduled between the teams at Recreation Park on May 26. But the newspaper article describing the success of game two contained an ominous addendum that raised doubts the series would continue: “There is talk of trouble over playing the full series, as previously agreed upon.”116

The trouble resulted from two factors. First, the NL’s opposition to the AA becoming a second major league. The senior league chose to dismiss the association as a substandard enterprise, offering an inferior product on the field. Refusing to recognize the major league status of the AA led to considerable friction between it and the NL.117 Second, the inclination of players to “jump” teams for better paychecks. NL clubs were prohibited from signing players who jumped from other league franchises. In addition, they could not play teams who had on their rosters players who had jumped from an NL club. Players who did so were blacklisted. Owners were not precluded, however, from signing players who jumped from clubs outside the league.118

John “Dasher” Troy signed to play with the Athletics for the 1882 season, but then altered course and signed with the NL’s Detroit Wolverines. Association officials immediately protested Detroit’s action and characterized the move as an attempt by the league to break up the AA.119 They insisted Detroit rescind the signing and tell Troy to honor his contract with the Athletics. Detroit balked, however, and the association retaliated by declaring Troy its first blacklisted player. In addition, AA officials announced that not only would association teams decline to play the Wolverines, they would also refuse to schedule games against any clubs that played Detroit.120

The Philadelphias were scheduled to play their first game against the Wolverines on May 29, and the Athletics signaled their objections to Reach by “indefinitely postponing” the game scheduled for May 26. The ostensible reason given was that the A’s had to play a makeup game against the St. Louis Browns that had been canceled due to inclement weather earlier in the season. But scheduling the makeup game at the last moment to deliberately conflict with the May 26 game, and leaving open-ended when the game against the Philadelphias would be rescheduled were intended to send an unmistakable message to Reach. Don’t play Detroit while Troy is on the team’s roster, or there will be no more games with the Athletics.121

The Philadelphias-Wolverines game occurred despite the warning. Reach had little choice as a member of the League Alliance with aspirations to join the NL. To refuse to play Detroit because it had signed Troy was sure to rile league owners, who could inflict far greater punishment on the Philadelphias by ordering all NL clubs not to play games against them, and perhaps even expel the franchise from the Alliance.

As expected, the association exacted retribution by preventing its teams from playing any additional games against the Philadelphias. The two games in May against the Athletics were the only ones Reach’s team would play against AA opponents in 1882.122

NL owners, realizing the financial drawbacks of the AA boycott, attempted to resolve the dispute over Dasher Troy in late June.123 If the association would reinstate him, then Detroit would release Troy to return to the Athletics. In a move that must have aggravated Reach, NL owners sweetened the pot by offering the A’s the opportunity to play all league clubs in Philadelphia after September 30. The Philadelphias would no longer have the exclusive right to play NL teams in the city for the last month of the season. The Athletics refused to consider the proposition.124

The breech between the NL and AA widened as the 1882 season progressed. One sportswriter assessed, “The prospect of an amicable adjustment of the difficulty is very dim.”125 The confrontation was aggravated by the continuing propensity of players to sign with a club in either the AA or NL, and then renege to sign at a higher salary with a team in the other organization. For example:

(Charlie) Bennett of the Detroits, who had signed to play with the Allegheny Club next season for $1,700 and who had received a bonus of $500 now seeks to recede from his contract in order to play with a League nine. The Allegheny directors refuse to take the money back, and threaten to expel Bennett unless he lives up to his contract.126

President Denny McKnight of the AA “declared war to the knife” with the NL over the issue of signing players who had jumped their contracts with the AA, and “promises that the names of many prominent players of the League, and, perhaps, managers, will appear on the black list of his Association.”127 Peace would not come between the association and league until after the 1882 season had concluded.128

Games Against Amateur Clubs

Although not nearly as lucrative at the gate as games against major-league clubs, Reach was obliged to schedule numerous contests against amateur competition — independent and college clubs. Doing so avoided big gaps in the schedule — a failing of the original 1877 League Alliance — and gave his players additional experience individually and as a team.129 While Reach had no illusions that matches against amateur players would be huge money-makers, he also realized a home game with a few hundred fans in the stands was more profitable than an empty ballpark with no game scheduled. His financial position also was strengthened by the fact that guaranteed minimum payments, and 50-50 sharing of gate receipts required for games against NL teams did not apply when amateur clubs visited Recreation Park. Reach further maximized the potential profitability of these games by scheduling most of them against local/regional amateur competitors. This reduced transportation costs and encouraged fans of amateur teams to attend games at Recreation Park by minimizing the distance they had to travel.

The Philadelphias played 40 games against independent and college clubs in 1882, racking up an impressive tally of 38 wins and two losses. This lopsided victory total enabled Reach’s team to squeeze out an overall winning average (.503) for the season. (See Appendix A below.)

Despite almost always losing against the Philadelphias, most amateur clubs gained a big advantage in playing Reach’s team by having some of the games played at their ballparks. While matches at Recreation Park would hopefully cover an amateur club’s costs and perhaps even generate a small profit, games against Philadelphia at home held the prospect of a big payday because they would likely draw larger crowds than games against other amateur clubs.130

Variations in the number of times the Philadelphias visited the home ballparks of amateur teams were considerable. For example, Reach’s team played the Merritts of Camden, New Jersey three times at Recreation Park and once at the Merritts’ ballpark. The Trenton, New Jersey club was visited three times by the Philadelphias, while the Trentons played at Recreation Park only once. The Atlantic City, New Jersey nine played in Philadelphia on four occasions, but never hosted Reach’s team at home.131

With the exception of the series against the Metropolitans, the only away games the Philadelphias played in 1882 were against independent and college clubs. Most were located in New Jersey, but Reach’s team traveled to New Haven, Connecticut in May to play the Yale College team twice.132 In addition, the Philadelphias made their only “western” road trip in September to play three games sequentially in the Pennsylvania cities of Reading, Pottsville, and Harrisburg.133

In addition to playing professional teams at their home ballparks, amateur franchises also were untrammeled by the squabbling that prevented NL and AA clubs from playing each other during most of the 1882 season. Amateur teams displayed no favoritism in arranging home and away games against members of both organizations, nor did league and association clubs seem to mind the crossover in scheduling. For example, the Brooklyn Atlantics traveled to Recreation Park to battle the Philadelphias on April 12, losing badly 15-1. Then, the Atlantics took on the Athletics at Oakdale Park on April 15 and were again pummeled 25-7.134

With some exceptions, games against amateur opponents at Recreation Park drew crowds in the low hundreds. There were, nevertheless, several noteworthy contests during the season that attracted a greater number of fans, and that constituted important “firsts” for the Philadelphia club as part of its inaugural campaign:

- As noted previously, a pitcher named “Buffington” (sic) threw the first no-hitter in club history on April 22. The second no-hitter occurred at home on May 1 when Hardie Henderson faced the Merritt nine “who did not make a base hit during the game.” Only three of the visitors reached base — two on walks and one on an error. The Philadelphias coasted to an 8-0 victory. 135

- In what was attributed to a “misunderstanding,” Buffalo was supposed to play the Philadelphias on June 13 — the Bisons’ first visit to the city — but instead, played Worcester that day. An estimated 3,000-4,000 people were outside Recreation Park waiting for the gates to open when it was announced the game would not be held. To not disappoint the crowd, an impromptu game was hastily arranged that featured Reach’s team against a “Picked Nine,” consisting of Philadelphias and amateur players. Most people left, but around 1,000 of them paid to watch the game, which Philadelphia won 12-5.136 Manager Phillips displayed a letter from Buffalo manager Jim O’Rourke after the game accepting June 13 as a date to play the Philadelphias. O’Rourke was severely criticized within baseball circles for failing to keep the engagement.137

- The Philadelphias played the Orion Club of Philadelphia at Recreation Park on July 19, their first game against a “colored” team. In yet another no-hitter, Neagle struck out 14 batters, including striking out the side in the seventh and eighth innings. The home team won convincingly 17-1 in a game that was witnessed by 2,000 spectators, “one third of them colored.” It was the only game played by Reach’s team against a “colored” club that season.138

- In another first for the Philadelphias, a team from a foreign country came to town to play a baseball game. The Atlantics of St. Thomas, Canada, visited for a two-game series on August 16 and 17. The Atlantics “were the championship baseball nine of Canada,” and their roster was comprised of “picked players from the Dominion.” The initial contest ended with Reach’s club on top 7-4. The Canadians played a competitive game “but lacked the experience necessary to cope successfully against such a nine as their opponents.” Neagle was in the box for the Philadelphias, and he tallied 11 strikeouts as Atlantic players were unable to overcome his “curved pitching.”139 In the second game, the Philadelphia nine again prevailed by a score of 2-0. Henderson handcuffed the Canadians in the contest. Each game attracted 800 people to the ballpark.140

By the end of the 1882 season, scheduling games against amateur clubs had clearly served its intended purpose. It avoided long periods of idleness in the Philadelphias’ schedule, crowd size was respectable — and sometimes more than that — at most games, and the contests helped Reach’s team take a key developmental step in preparing for its ascension to the National League.

Moving Up to the National League

There was never any doubt Philadelphia’s and the Metropolitans’ admittance to a resurrected League Alliance in 1882 was an interim step to facilitate their membership in the NL the following year. Their path was made that much easier when League President William Hulbert died on April 10, 1882. With his passing, resistance within the league’s leadership to welcoming both cities into the fold ended. Arthur Soden, who favored dropping small market teams from the league’s ranks and replacing them with clubs from large metropolitan areas, succeeded Hulbert as president.141

That the Troy and Worcester franchises were on the chopping block was no secret as the 1882 campaign progressed. As early as July, rumors were rife that Philadelphia would take Worcester’s place in the league.142 Confirmation of same came at the NL owners meeting in Philadelphia on September 22. It was announced that Troy and Worcester had resigned from the league effective at the end of the season, and that the Metropolitans and Philadelphias had filed applications for membership to replace them. The reason cited by the league for Troy’s and Worcester’s decision was that the clubs had “fared very badly during the last few seasons, both financially and in the race for the pennant … So by allowing the Empire and Quaker Cities to fill the places left vacant by the retirement of Troy and Worcester every other club in the association will benefit by it financially.”143

When the applications for withdrawal were presented at the owners meeting, not a single delegate objected, according to one newspaper report. Confirmation that the resulting openings were reserved for New York and Philadelphia came when the league received and promptly rejected applications from several AA clubs to join.144

Officials of the Troy and Worcester franchises denied vehemently they had voluntarily resigned their memberships in the NL, claiming that a resolution forcing them out had been introduced at the meeting and passed 6-2 (Troy and Worcester voting in the negative). But the die was cast. League owners had determined neither city had a sufficient population to give visiting clubs a share of gate money adequate to pay their expenses. In one sportswriter’s opinion, “It was simply a question of business whether two non-paying cities should be continued in the co-partnership when two paying cities could be secured to take their place.”145

With Worcester’s demise official, several players began leaving the team at the end of September to play out the season with other clubs. One of these was Jackie Hayes, an able catcher, who joined the Philadelphias. His acquisition held the prospect of solving the team’s catching problem. Hayes’s first game with his new club was on October 4 against the Buffalo Bisons. A game summary lauded his performance:

Hayes, late of the Worcesters, made his first appearance with the home nine, and his playing behind the plate was the feature of the game. He put out two, assisted twice, had no errors and made two base hits and two runs.146

After the game, Hayes succeeded in getting a ten-dollar advance on his salary from Manager Barnie, and then skipped town with the Bisons to finish up the season with that club. The irony of Hayes jumping from Worcester to Philadelphia — the club that would replace Worcester in the NL — and then jumping after one game to another league team after he extracted an advance on his salary — presumably was not lost on Reach or Barnie.147

The applications from New York and Philadelphia would be decided at the December owners meeting, but in a surprising development — given all the work that had been done to facilitate their membership — the Metropolitans decided in October to join the AA in 1883.148 Another New York-based club, the New Yorks, took its place in the league.149

At the December 7, 1882, NL owners meeting in Providence, Philadelphia and New York were admitted as members of the league.150 Given how histories of the franchise portray Reach’s eagerness to join the NL, this should have been a joyous moment for him.151 But was it? The Metropolitans had already decided to abandon the league in favor of membership in the association, and there is evidence Reach was also reconsidering. A newspaper article revealed threats were necessary to convince him to follow through on the club’s application to join the league:

The reason that the Philadelphia Club entered the League was because Al Reach was told that if he did not, a League club would be placed in Philadelphia which would throw out the League Alliance Club.152

Whatever doubts Reach harbored about becoming a member of the NL in 1883 were almost certainly attributable to the less favorable financial position his team would inhabit compared to participating in the League Alliance in 1882:

- The club would be compelled to charge the league minimum admittance fee of 50 cents, vice the 25 cents it charged while a member of the Alliance. As Bancroft’s figures, cited earlier, illustrate, a 100 percent increase in the admittance fee for a ticket might dissuade people from attending games.

- Reach’s costs for operating the club would increase dramatically once a member of the NL. In 1882, Philadelphia was able to play 80 percent (111 of 139) of its games at home, including all of the matches against NL opponents. The balance would shift to a 50-50 split as Reach’s team would be scheduled to play half its games at home and half on the road against league teams. The hike in away games meant travel costs — transportation, meals, and accommodations — would escalate dramatically for Philadelphia in 1883.

- As a member of the NL, games against amateur clubs dropped off the schedule.153 In 1882, the Philadelphias played 30 percent (40 of 139) of their games against such teams, and of those, 70 percent (28 of 40) were played at home. Eliminating those matches also contributed to Reach’s team spending much more time on the road in 1883, thereby increasing travel costs further.

- More games against NL opponents in 1883 (99) versus 1882 (65) would cause Reach to share a greater percentage of gate receipts with visiting teams, as league rules mandated. The more unfavorable split in ticket revenue was especially apparent with the simultaneous deletion of games against amateur clubs from the schedule. Reach got to keep a greater percentage of the admission fees from the latter matches.154

- Reach also recognized that despite his club having a year of experience and retaining some players from the 1882 roster, the 1883 Philadelphias were still going to have a difficult time competing against other NL clubs. He must have wondered if spectators would come to the ballpark to see his team lose many more games than it won, especially as the season continued. Reach’s worst fears were realized when the club posted a 17-81 record. Over 135 years later, this remains the worst winning percentage in a season for the franchise.155

- (This bullet needs to be removed.)

Operating the Philadelphias during their inaugural year in the NL was expensive, and Reach lost money.156 Some believed he had erred, and suggested he cut his losses by bailing out of the enterprise.157 It is doubtful they fully appreciated that Reach — faced with a threat from NL owners to place another franchise in Philadelphia if he did not join the league — had little choice but to acquiesce and persevere.158 To his credit, moreover, Reach remained determined to make his club the premiere baseball team in the city.

Whatever misgivings Reach may have held about the future, participating in the League Alliance was a crucial step in the emergence of the Philadelphia National League Baseball Club. It provided a necessary segue for his team to form, organize, and mature in preparation for becoming a major-league franchisee the next year. The alliance experience also proved to NL owners that Philadelphia’s membership in the league was advantageous, and that the city could support two professional clubs simultaneously, even when the marquee Athletics belonged to a rival organization. The League Alliance experiment worked. Philadelphia remains a member of MLB, while the Athletics and AA have long since receded into baseball history.

The Nickname Conundrum

The Philadelphia National League Club’s longstanding nickname of “Phillies” has been deliberately omitted from the text until this point to separately examine how this name emerged and became associated with Reach’s club. Also requiring investigation is the commonly held belief the Philadelphia franchise had a nickname other than Phillies at its outset.

The corporate name of Reach’s franchise in early 1882 was the Philadelphia Ball Club and Sporting Association. Later that year, it was changed to the Philadelphia Ball Club and Exhibition Company.159 This author has been unable to discover any information from contemporary sources affirming the Philadelphia club officially adopted a specific nickname during this period.160 The only evidence from a club official that Phillies was the preferred sobriquet comes from a quotation attributed to Reach that has been cited in some histories of the team. The moniker allegedly appealed to Reach because, “It tells you who we are and where we’re from.”161 When it is used in secondary publications, however, no citation is provided referencing a primary source where the quotation first appeared. Moreover, research by this author has failed to discover the quotation in any source contemporary to the period. This author questions whether Reach actually uttered those words, and suspects the quotation was later attributed to him as a simple and convenient way to explain how the Philadelphia NL team got its nickname.

In addition, judgments that Reach originated Phillies as a creative yet sensible moniker for his team ignores the fact it predates his club. In 1881, two Philadelphia-based teams joined the newly-created Eastern Championship Association. One was the well-established Athletics, and the other was an embryonic club to which the sobriquet Phillies was attached in newspaper game reporting.162 That represented the first application of the nickname to a Philadelphia baseball club. The team lasted only a month before folding — a fate that befell many franchises of that era. Nevertheless, Reach didn’t invent the name Phillies for his club. Sportswriters simply transferred it from the previous year’s Philadelphia team upon which the nickname had been bestowed.163 Reach’s Phillies were regarded as the successor to the ECA Phillies, and for that reason inherited the same nickname.

Some histories of the Philadelphia NL franchise date the Phillies nickname to 1883 when the club joined the NL.164 This is erroneous. When used in reference to Reach’s team, the sobriquet first appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer on April 14, 1882, in a description of a game the Phillies played the previous day at Recreation Park against Princeton College.165 The moniker continued to appear periodically in city newspapers throughout the rest of the Phillies’ season in the League Alliance.166 Newspapers published in other cities also identified the club as the Phillies in their reporting.167

If frequency of a nickname contained in newspaper coverage is the best indicator of validity, then there is no question Reach’s club was called the “Philadelphias.” That moniker appeared far more frequently in period newspaper reporting than any other referring to the ballclub. Additional terms used periodically to identify the team included “Philadelphia Club” and “Philadelphia nine.”168 But none were used as often as Philadelphias, and it continued to be the dominant nickname for the team in newspaper reporting for several years until Phillies eventually supplanted it.

Some histories of the Philadelphia NL Baseball Club state the team’s first nickname was “Quakers,” which was later superseded by Phillies. For example, David Nemec, in his book on nineteeth century baseball, identifies the franchise as the Philadelphia Quakers for 1883-84, and then updates the moniker for the 1885 season and beyond by replacing Quakers with Phillies.169 Other team histories judge the nickname was Phillies from the beginning.170

Regarding the genesis of “Quakers,” Lieb writes, “The nickname of the old National Association Philadelphias — the Quakers — persisted, and for years a number of Philadelphia dailies preferred to refer to the new club as the Quakers.”171 That is an odd explanation for Quakers being the first nickname since none of the Philadelphia-based members of the National Association (NA), which operated from 1871-75, had that moniker.172 While some newspapers may have used Quakers to refer to Reach’s team, others did not. For example, the Philadelphia Inquirer — a major newspaper in the city — did not used it once in its reporting on the club over the 1882-83 seasons; nor did the New York Clipper, which provided extensive coverage of major league baseball over those years, including games played by Philadelphia teams. This author judges as dubious the proposition Quakers was the official — or even commonly-accepted — nickname of the team given its absence in major newspaper coverage of the club at the time. 173

Moreover, it makes little sense that sports reporters would reach back eight years to the NA era to resurrect a nickname for the new Philadelphia club, especially when none of the Philadelphia-based teams in the NA actually used it. A more persuasive explanation is that they reached back only one year to the 1881 ECA Philadelphia club and applied its moniker to the 1882 League Alliance Philadelphia team.174 In both years, Phillies was used to distinguish the team from the better-known Athletics, and to provide a shorthanded but still obvious way to identify the club in game accounts.

There will always be some vagueness about the nickname of the Philadelphia NL club during its earliest years because the franchise never embraced a particular name officially, and newspapers used a variety of monikers to refer to the team in their reporting. In this author’s view, a more evidentially sound case can be made that Phillies was applied as the franchise’s sobriquet from the outset rather than Quakers. It was simply transferred by sports writers from the failed 1881 ECA club to the new 1882 League Alliance club.

Although several nicknames were used to refer to the Philadelphia NL club during its formative years, the use of others faded and Phillies emerged as the consensus choice for the team name. It is important to add, moreover, the adoption of Phillies evolved over time from multiple sources of reporting on the team, rather than at a specific time through a formal declaration by the club. Regardless of the ambiguity surrounding its origin, the Philadelphia NL and MLB franchise has been known as the Phillies for over 135 years, and the nickname will undoubtedly remain into the indefinite future.

ROBERT D. WARRINGTON is a native Philadelphian who writes about the city’s baseball past.

Photo caption

Front cover of Philadelphia Phillies’ 1882 scorecard featuring an artist’s depiction of Recreation Park and the various sports played at the site — baseball, bicycling, foot races, etc. The name of the visiting team would be changed each series. (COURTESY OF ROBERT WARRINGTON)

Notes

1 Frederick Lieb and Stan Baumgartner, The Philadelphia Phillies (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1953), 11-13.

2 “Baseball in Philadelphia,” New York Clipper, October 15, 1881.

3 For a biographic sketch of Al Reach as a player, businessman, and owner, see, Rich Westcott and Frank Bilovsky, The Phillies Encyclopedia, 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004), 365-367.

4 David M. Jordan, Occasional Glory: A History of the Philadelphia Phillies (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2002), 6. Jordan notes that Reach’s “love of baseball” was one of the motivating factors in his decision to start a baseball club.

5 Ibid. Philadelphia’s population had reached 847,000 by 1880.

6 Lieb and Baumgartner, 12.

7 One newspaper reporter commented, “There can be no doubt of the pecuniary success of Al Reach’s new enterprise.” “Opening the Season in Philadelphia,” New York Clipper, April 15, 1882.

8 In 1882, the club was called the Athletic, just as the New York club was called the Metropolitan. These and other names have been pluralized in the text to reflect contemporary usage, and because the teams themselves began to pluralize them after a few years.

9 David Shiffert, Base Ball in Philadelphia, (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2006), 4. Shiffert writes that in 1865, Reach became the first ballplayer to change cities for a salary, jumping from Brooklyn to the Athletics of Philadelphia.

10 David Nemec, The Beer and Whiskey League (New York: Lyons & Burford), 20-21.

11 Ibid., 14-16.

12 “Baseball,” New York Clipper, October 8, 1881.

13 New York Clipper, October 15, 1881.

14 “Baseball,” New York Clipper, October 29, 1881. Nemec states that only Phillips represented the new Philadelphia club at the November 2 meeting. Nemec, Beer and Whiskey, 21-22.

15 Ibid. According to Nemec, Chick Fulmer, manager of the Athletics, pledged his club “could put up $5,000 that very day” to underscore its financial solvency. Phillips, speaking for the new Philadelphia club, claimed his club had plenty of financial backing but did not specify a figure.

16 Shiffert, 4.

17 Nemec, 22.

18 New York Clipper, October 15, 1881.

19 The Metropolitans chose not to join the AA since doing so would mean foregoing potentially lucrative games against NL clubs during the 1882 season. Representatives from the club who attended the meeting, James Mutrie and W.S. Appleton, also doubted the long-term viability of the AA. Asked to leave the November 2 meeting and come back when they were ready to commit, the pair exited and never returned. Nemec, Beer and Whiskey, 21. Brock Helander, The League Alliance, https://sabr.org/bioproj/topic/league-alliance

20 Nemec, 23.

21 Lieb and Baumgartner, 12. According to them, NL president Mills was later quoted as saying, “We’ve got to get these big cities back into our league. Both New York and Philadelphia have tremendous futures, and some day their populations will be in the millions. If we permit the American Association to entrench itself in these cities, the Association — not we — will be the real big league.” Whether Mills uttered these words, or they sprang from the author’s fertile mind is unknown because Lieb and Baumgartner didn’t source their history of the Phillies and were suspected of manufacturing quotations for their books to enliven the text and validate their analysis and conclusions.

22 David Nemec, The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Major League Baseball (New York: Donald I. Fine, 1997), 87.

23 Ibid., 173.

24 “A League Club,” New York Clipper, July 16, 1881.

25 Nemec, Great Encyclopedia, 156, 176.

26 Ibid., 173.

27 Michael Haupert, “William Hulbert,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/d1d420b3

28 “The American Association,” New York Clipper, March 25, 1882.

29 Helander.

30 Ibid.

31 Ibid. Helander identifies 13 clubs as “generally recognized as members of the League Alliance.” Baseball-Reference.com lists 16 more clubs as members of the Alliance. https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/league.cgi?id=a9132541

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid.

34 Bill Lamb, John Day, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/c281a493

35 Helander.

36 A curious report appeared in the New York Clipper newspaper that offered an entirely different version of what occurred at the December 7 NL owners meeting, It reads:

The Metropolitan Club and the Philadelphia team said to be under the management of Al Reach and H.B. Phillips were each offered membership in the League. The Mets declined on account of the fifty-cent tariff, while Reach and Phillips cannot secure sufficient first-class talent to take the risk, although it is rumored that propositions have been made to Ferguson’s Troy team, and also to the Providence nine, to locate in Philadelphia as a League club.

This author has not found any corroborating evidence to affirm Philadelphia and New York were considered for admittance to the NL at the December meeting; that New York and Philadelphia declined the opportunity; or, that the NL proposed to the Troy and Providence clubs that one of them transfer to Philadelphia. All information this author has examined indicates New York and Philadelphia were offered membership in the League Alliance; both accepted, and no entreaties were made to existing NL teams to have one of them relocate to Philadelphia. “Baseball,” New York Clipper, December 10, 1881.

37 This condition applied only to Philadelphia because New York was not a member of the American Association or National League in 1882. The city would be represented in both organizations in 1883, just like Philadelphia.

38 “Baseball,” New York Clipper, December 17, 1881.

39 Rich Westcott, Philadelphia’s Old Ballparks, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996), 9-10.

40 Robert D. Warrington, “Philadelphia in the 1881 Eastern Championship Association,” Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 48, No 1 (Spring, 2019), 78-85.

41 Phillips announced in October 1881 that the Philadelphias wanted to lease the grounds for the upcoming season. He stated all existing buildings would be demolished as would the fence surrounding the lot. The baseball diamond also would be reconfigured to increase the distance of center field. He estimated the costs of these changes at “two to three thousand dollars.” New York Clipper, October 15, 1881.

42 Reach may have been told this initially by the owner of the land to pressure him into offering more money to rent it.

43 That Reach intended to lease Recreation Park for his ball club is recorded in “The Philadelphia Club”, New York Clipper, December 24, 1881. The initial unavailability of the ballpark and Reach’s negotiations to use the circus lot at Broad and Federal Streets are noted in “Baseball,” New York Clipper, January 7, 1882.

44 Westcott. He records the dimensions of the playing fields at: 330 feet down the left field line; 369 feet to straightaway center field; 369 feet to right-center; and, 247 feet down the right field line. Seventy-nine feet separated home plate from the grandstand behind it. The sharply disparate dimensions of the playing field were caused by the contorted shape of the land on which it was located.

45 “The Game in Philadelphia,” New York Clipper, April 1, 1882. An earlier depiction of the ballpark contained slightly different figures for seating capacities of the grandstand and bleachers, and also furnished additional information about the ballpark’s features:

The seating capacity will be about 3,000. Including 1,300 covered seats in a new grandstand which is to be erected. The center portion of the stand, containing 500 seats, will be reserved for subscribers, season ticket holders and ladies. Along the rightfield side open seats — with footrests — for 1,000 persons, and along the leftfield side the same seats for 700 people will be erected. A reporters’ stand will be constructed on top of the other stand with accommodations for twenty-five persons (press and visiting club alone) … A clubroom will be under the west end of the stand, and will include dressing room with closets, washbasins and water closets. At centerfield will be erected a large blackboard, on which will be displayed the scores of innings of League and League Alliance games being played on the days the home teams play.

New York Clipper, December 24, 1881.

46 In preparing Recreation Park to be his team’s home, Reach also had the grounds arranged for other sports that could be played on off days of the baseball season. As one newspaper reporter noted, “Tracks for foot racing, bicycling, etc., have been prepared, and the ground is so arranged that almost every known field sport can be indulged in upon it.” New York Clipper, April 1, 1882.

47 Like Reach’s decision to improve Recreation Park before the start of the 1882 season, management of the Athletics also invested significant sums to upgrade Oakdale Park. The grounds were sodded and leveled, and a new border fence and grandstand erected. The grandstand, as described in a contemporary newspaper account, was two hundred feet long and sat 1,500 people. It was divided into three sections, including one for season ticket holders that had cane-seated chairs, and another reserved for ladies and gentlemen accompanying them. The reporters’ stand was placed on top of the pavilion and situated to the rear of the catcher’s position. It held 20 reporters. “The Athletics Club,” New York Clipper, February 18, 1882. Oakdale Park was located on a plot of land bordered by Huntingdon Street, 11th Street, Cumberland Street, and 12th Street in Philadelphia. The AA Athletics used it as their home ballpark for only one year. The club moved to the Jefferson Street Grounds for the 1883 season. Oakdale Park was torn down shortly thereafter. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oakdale_Park

48 “Baseball,” New York Clipper, January 14, 1882. As indicated in note 45, when Recreation Park was rehabilitated by Al Reach, the grounds were designed so that sporting events other than baseball could be played at the facility.

49 New York Clipper, February 18, 1882.

50“Opening the Season in Philadelphia,” New York Clipper, April 15, 1882.

51 Box scores appearing in the Philadelphia Inquirer, New York Clipper and New York Times between May — October 1882 were examined to assess the Philadelphia club’s regular starting lineup during that period.

52 The following sources provided information on the careers of baseball players identified in the Philadelphia club’s lineup: Baseball-Reference.com; Baseball Almanac; Nemec, Great Encyclopedia.

53 Pop Corkhill was badly injured in a game against Boston on October 7 and was out for the rest of the season. “Field Sports,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 9, 1882.

54 Ibid. Tim Manning began the 1882 season with the Providence Grays but was released by that team in June and signed by Philadelphia. “Baseball,” New York Clipper, June 24, 1882. Corkhill had no big league experience prior to the 1882 season, but would go on to play with teams in the AA and NL into the early 1890s. https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/c/corkhpo01.shtml. John Manning and Tim Manning were not closely related. The former was born in Braintree, Massachusetts in December, 1853, and the latter was also born in December 1853, but in Henley-on-the-Thames, England. Nemec, Great Encyclopedia, 694, 730.

55 Two of the players inserted at catcher early in the season to evaluate their talent were Bill McCloskey and Marshall Quinton. Neither lasted very long. Both men appeared as catcher in the Philadelphia lineup during a game played on April 12, 1882, against the Atlantics of Brooklyn. When Philadelphia switched pitchers in the eighth inning, the catchers were also changed. “Baseball,” New York Clipper, April 22, 1882. Another player given a tryout as catcher was FNU Morris. One of the reasons he lasted only a short period with the club may have been his demeanor. In a game played on June 14, Morris was ordered off the field by team captain John Manning “for disobeying orders.” “An Easy Victory,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 15, 1882.

56 “Baseball,” New York Clipper, September 9, 1882.