Baseball Archeology in Cuba: A Trip to Güines

This article was written by Mark Rucker

This article was published in Fall 2019 Baseball Research Journal

Visiting Cuba is like tripping in a time machine. We’re not talking about a beach vacation at Varadero, but a visitation to the living, working Cuba. A Cuba where baseball is woven into the shirts they wear, is the caffeine in their coffee, and the excitement in their voices. When you are there, you’ll find the time traveler gets a different version of now and then. In Cuba there is the pre- and post-Revolutionary country, a national history more seen as a continuity today than in the recent past, but still a history divided, one capitalist and one socialist.

The passengers on this small scale adventure include Sr. Ismael Séne, our magnificent intellectual host with his photographic memory, knowing all things baseball, old and new, Peter Bjarkman, the English-speaking master of Cuba’s modern game, our driver, and the camera wielding author, who planned this jaunt with no guarantee of success.

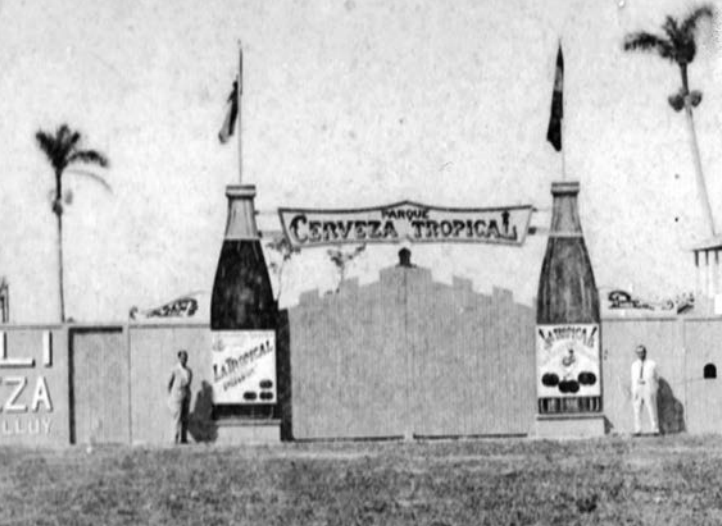

The inspiration for our one-day trip was a group of photographs from the winter ball season of 1927–28. They were taken at a ballpark in Güines, a small city of now 70,000, 50 km. or so southeast of Havana. The photos — a group of sixteen 7”x5” prints, mounted on decorative 10”x8” boards — started turning up in the capital city a few years earlier in an astounding state of preservation, arriving in small groups, until almost the entire collection was assembled (16 of 18 are present). The sauna-like climate on the island is rampantly destructive to paper, and photos usually suffer. Though I had been doing photo research in Cuban baseball for over fifteen years at that point, no picture had ever before appeared of Estadio Tropical Cerveza (Tropical Beer Park), nor had I seen reference to it, nor had I seen any mention of the photographer, Raphael Santiago of Calle M. Gomez 120, Güines, whose name was embossed in each print.

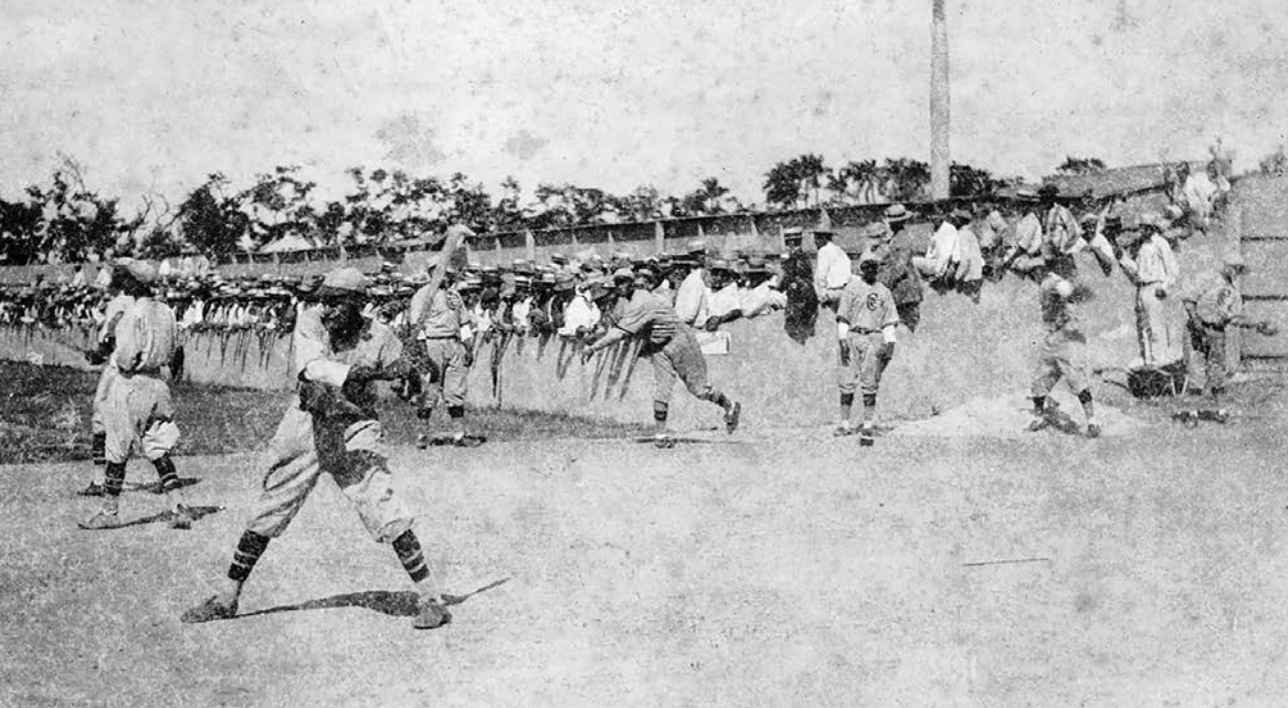

The most exciting feature of this group of photographs was not the record of the physical features of the park, nor the parade of old automobiles entering through the decorated gateway, nor the close up views of the well dressed fans, nor even the pre-game warm-up activity in front of the stands. Instead, it was a team shot of the Cuba Baseball Club, an integrated professional team from the top league in the country. This club, one of the most amazing to take the field in all of baseball history, was composed of big names from Cuba and an all star contingent from the US Negro Leagues.

Managing “Cuba” was Armando Marsans, one of the first Cubans to wear a major league uniform in the twentieth century, playing eight years in the American, the National, and the Federal Leagues. Marsans’ pitching staff features Willie Foster, newly of the Baseball Hall of Fame, Willie Powell, small and sturdy right-hander, along with Cuban Basilio “The Witch” Rosell. Sharing the infield and the outfield were Judy Johnson and Oscar Charleston, monster stars both in the Negro Leagues and in Cooperstown, Walter “Steel Arm” Davis, from the Chicago American Giants, Cubans Pelayo Chacón, who played in Cuba from 1908 to 1932, Cando Lopez, Francisco Correa, and José Perez. The catcher was Larry Brown, whose defensive skills and strong arm were legendary.

We were hoping we could find the site of this forgotten ballpark, as then the photos would take on more meaning, and we might even find some ghostly evidence of these long lost players. So, we headed south, past Cotorro, San Jose de las Lajas, and other suburban towns that ring the south side of Havana. Shortly after leaving the hubbub behind, we were passing horse carts on our two-lane road, along with reeking, wheezing agricultural trucks and 1930s tractors. In short order our tan colored Lada was driving along the main thoroughfare into town, where we stopped at Güines’ stadium, almost sparkling with its bright green grass and fresh coat of red and ochre paint. The stadium hosts a good number of games annually, involving the Havana Province’s three national series teams, Industriales, Metropolitanos, and Habana during the winter season, which usually runs from November to April. There was no ball game on this day, but the guard on duty was not sure where the old field had been, so he directed us into the center of town for more information.

On we went making inquiries, and found that, indeed, there was an old ballpark outside of town, though no one seemed to know its former name. Heading eastward for a short while, the houses soon grew farther apart, the city street grid disappeared, and after a few twists and turns we were parking across the street from what had been Estadio Tropical Cerveza. The old entrance had been replaced by a now weather-beaten, stylized gateway, which was connected to a high cement wall painted white. That outer, higher wall joined with the outfield wall to the north, and together they encircled the entire field. “352” was painted on the outfield wall where the cement baseline intersected it, matching symmetrically the right field line. Another shorter cement wall had been constructed within and parallel to the perimeter structure, separating the field from the spectators, to which were attached two cement above-ground dugouts. The grass was short, the pitching rubber and home plate still in place, so some kind of ball was still being played here. The baselines were composed of poured cement strips about 4 inches wide, sitting a little above ground level, no doubt a hazard for hustling runners and fielders playing close by. What we were looking at was a cement construction ballpark in total disrepair. Between the eras of the totally wood-framed Beer Park and the present day ruin, a reconstruction project had occurred, transforming the field into a 1930s-40s art deco style structure, one probably used extensively throughout the 1950s. In between the two parallel cement walls, now separated from the playing field, the crumbling cement foundations for the old grandstands were still clearly in place, forming patterns in the ground like concrete footprints.

By using the photos to match our locations on the field we were able to figure out where all the seating areas had been placed, where the cars parked, areas designated for pre-game warm-ups, and the location of the other field structures where four teams had posed. Since palm trees grow for hundreds of years, we thought we might match the trees in the photos with the trees of today, but younger palms had intervened.

We strolled about for most of an hour noting features that other photographs in the group revealed, like the location of the benches in front of the grandstands, or where the Cuba team players warming up five in a row intersected with their opponents, or the fact that the paved street we parked on did not exist in 1928, or how very large the park had been and still was. Back at the time of the photos, Tropical Cerveza could likely have held 10,000 fans. The photos from 1927 indicate that a crowd of such a large size could have witnessed the Cuba team in Güines.

We got an historical buzz, if not an ectoplasmic visitation. But as I turned my head to leave, I could have sworn that I saw from the corner of my eye long, tall Willie Foster, arms and legs in motion, throwing warm up tosses to Larry Brown, with Oscar Charleston shouting exhortations from the beyond.

MARK RUCKER is a photographic historian and a longtime SABR member. He was co-founder of SABR’s Nineteenth Century Research Committee with John Thorn, and has been involved in publishing since the mid-1970s. His companies Transcendental Graphics and The Rucker Archive provide access to rare and surprising images from long ago.

On the way to Güines, heading South from Havana, we encountered the past in the form of a horse cart.

In the 1926–27 season the front gate of Estadio Cerveza Tropical was an elaborate entrance to the field, flanked by the proud owners of the facility.

The front gate of the old field at Güines in 2007, where Peter Bjarkman establishes the scale of the present day entrance.

Cars entering the complex for a game late in 1926.

In front of the grandstands, a pitcher from one of the Güines teams warms up before the contest. The crowd that has packed the grandstands is ready to start.

Today all that is left of the grandstands are the cement structures left in the ground. The camera is in a location which would have been behind the old stands.

The Cuba Base Ball Club warms up before a game at Güines in 1926. This remarkable team fielded stars at almost every position. Here we see warming up at Güines (L-R) Pepín Perez, Pelayo Chacón, Walter Davis hitting fungos, and behind his bat is Oscar Charleston. The four pitchers in the distance to the right are Willie Foster, Willie Powell, Basilio “Brujo” Rosell, and an unknown southpaw.

Long gone are the cheering crowds in the bleachers, the shouts of the vendors, and the crack of the ball off the bat. Instead, we see cinder block dugouts and cement walls, in the seldom-used field on the eastern outskirts of Güines.

A gathering of rooters posed for a photograph near the grandstand at Güines without revealing their team affiliation. Not even a logo. But they do provide a before photo for the after, which was taken in the same spot in 2007.

The fans in Güines came in all ages and sexes. This entertaining shot of los fanaticos, who filled the grandstand at Estadio Cerveza Tropical, shows the broad base of support the game had even in small towns in Cuba.

Where the fans once jumped and shouted, only the foundations are left.

Cuba Baseball Club poses during their visit to the Estadio in Güines. This stellar crew played together for only one year, and did not win the pennant. They were: Top row (L-R) Willie Foster, Larry Brown, Cando Lopez, Oscar Charleston, Willie Powell, unknown, Cuco Correa. Front row Pelayo Chacon, Judy Johnson, Rogelio Crespo, Basilio Rosell, Walter Davis.