Babe Ruth and Cricket

This article was written by Glen Sparks

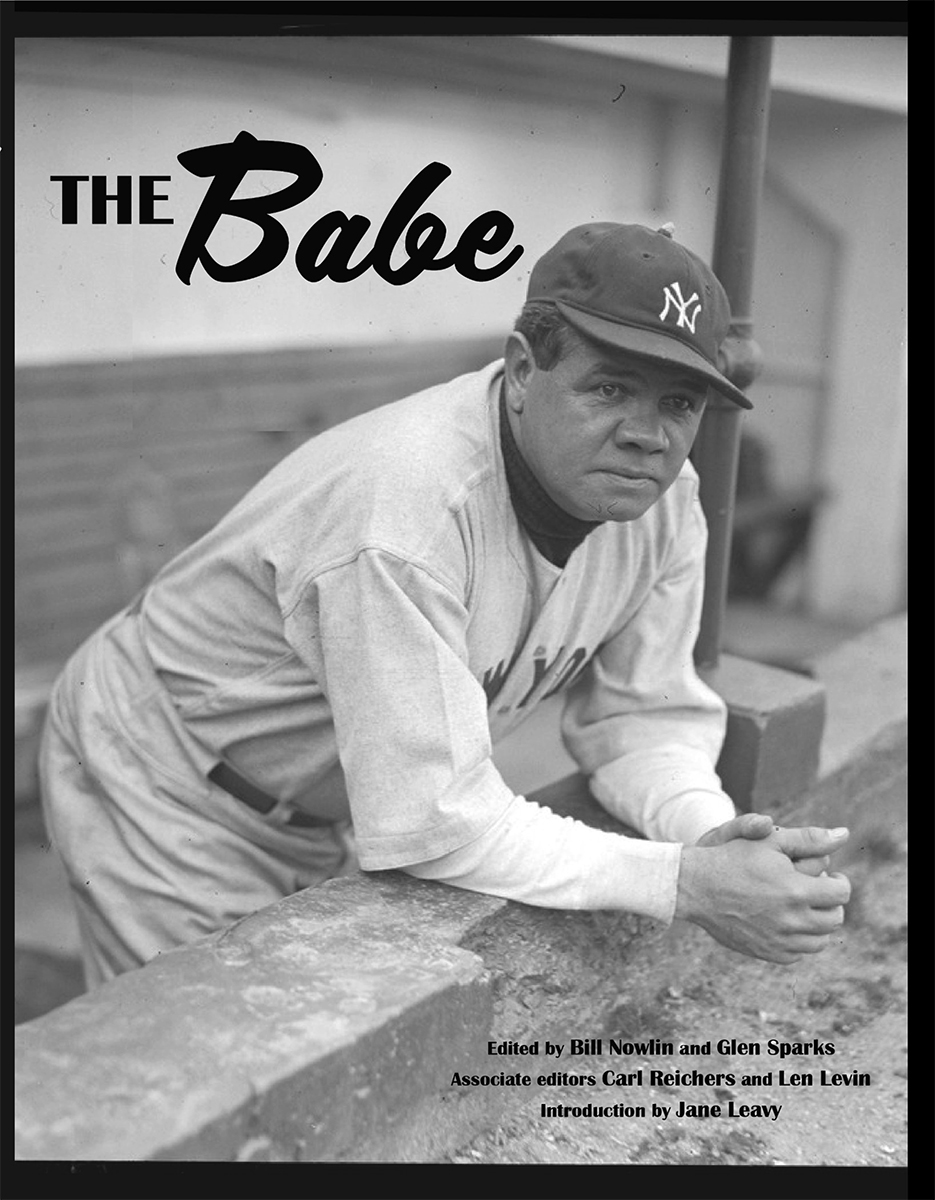

This article was published in The Babe (2019)

Babe Ruth turned his cricket bat into a broken, splintered mess. Baseball’s great home-run hitter had just smashed an hour’s worth of bowling (cricket’s term for “pitching”). He whacked balls all over a “subterranean” field near the Thames River in London. Alan Fairfax, formerly a top Australian player, coached Ruth and marveled at his pupil’s bountiful swing. “I wish I could have him for a fortnight,” Fairfax declared. “I could make one of the world’s greatest batsmen out of him.”1

Babe Ruth turned his cricket bat into a broken, splintered mess. Baseball’s great home-run hitter had just smashed an hour’s worth of bowling (cricket’s term for “pitching”). He whacked balls all over a “subterranean” field near the Thames River in London. Alan Fairfax, formerly a top Australian player, coached Ruth and marveled at his pupil’s bountiful swing. “I wish I could have him for a fortnight,” Fairfax declared. “I could make one of the world’s greatest batsmen out of him.”1

Babe took his cuts in February of 1935, near the end of a worldwide tour. Just a few months earlier, he completed his 21st season in the major leagues, and his 15th campaign – most of them glorious – as a Yankee. He claimed 708 home runs, the all-time mark by a long shot, and led the majors in that category 12 times. Fans and sportswriters called him the Big Bam, the Sultan of Swat, and the Maharaja of Mash. He was near the end of his playing career.

All sorts of rumors swirled around Ruth’s future after he hit 22 homers for the ’34 Yanks. He said for several years that he longed to manage a big-league ballclub. Many critics said the hard-living Ruth could barely manage himself. How could he manage others? Some wanted to give him a chance. Maybe.

According to one rumor, former Yankees co-owner Col. T.L Huston hoped to buy the Brooklyn Dodgers and hire Babe as skipper. Huston called the rumor “absolutely authentic.” He continued: “I have no desire to ventilate the affairs of the Brooklyn club, as we have always been friends. I believe Babe Ruth would make as efficient a manager as any of the present major league managers and would throw away no more games than they do.”2

Also, the House of David, a religious society and traveling band of talented baseball players, reportedly offered Ruth a $35,000 contract. The Babe wouldn’t have to grow a beard, unlike others on the House roster. “We’ll take him with a naked face, so the folks will know it’s really Babe Ruth,” according to one House veteran.3

In the fall of 1934, Ruth joined a team of American League All-Stars for an offseason tour of Japan. The group, led by Philadelphia Athletics owner and manager Connie Mack, included Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Charlie Gehringer, and others. “I ran the ball team on the field,” Ruth contended.4 It was a goodwill venture during a time of increasing tension between the two nations. Babe invited his wife, Claire, and older daughter, Julia, 18. Younger daughter Dorothy, 13 years old, stayed at home with relatives. Dorothy brooded over the slight. Supposedly, Julia went along as a way to celebrate her recent high-school graduation. Dorothy scoffed. “Well, if that trip was a graduation present, then Julia graduated about 15 times in five years,” Dorothy wrote in My Dad, The Babe, published in 1988.5

Mack told the players during a meeting that they must maintain their best behavior. Ruth, prone to misbehavior, sat in the front row and promised to obey the rules. It would be worth the Bambino’s while. Supposedly, Mack had some interest in hiring Ruth as the next Athletics manager. Baseball’s Great Tactician would turn 72 on December 22. Maybe it was time for a man born in the first full year of the US Civil War to hang up his straw hat, plus his managerial outfit of suit and tie, and hire a younger man.

The Empress of Japan left Vancouver, British Columbia, on October 20, 1934, all-stars aboard, and took several days to cross the Pacific Ocean. Long enough for Ruth and Gehrig to get on each other’s nerves. The longtime teammates, former fishing buddies, and friendly rivals during an exhibition tour – the Larrupin’ Lous and Bustin’ Babes played a series of games after the 1927 World Series – had fallen out of favor with each other. Maybe the whole fuss began over a crack that Gehrig’s mother, Christina, made a year earlier about how the Ruths dressed Dorothy in hand-me-downs. Julia, meanwhile, dressed in style. Ruth told Gehrig that Christina should mind her own business. Well, those were next to fighting words. The Iron Horse, then and there, just about quit speaking to the Babe.6

At one point Gehrig, according to Leigh Montville in The Big Bam, walked into Ruth’s stateroom and saw his tipsy bride talking with the Babe. What else had gone on? Lou was furious. He knew all about the reputation of one George Herman Ruth. Eleanor Gehrig, though, wrote in My Luke and I that Claire Ruth had offered the invitation. Babe sat in the room “like a Buddha figure, cross-legged and surrounded by an empire of caviar and champagne.”7 Eleanor joined the party. She left two hours later and with the ship’s horn bursting out a signal for a body overboard. A frantic Lou Gehrig could not find his wife. He worried that she had fallen into the deep. “The only place Lou had never thought to check out was Babe Ruth’s cabin.”8

Yes, Ruth and Eleanor knew one another. Eleanor grew up in Chicago. She played poker and smoked cigarettes in public (gasp!) and liked a stiff drink. She loved to attend parties. “Before she had known, Gehrig, she had known the Babe,” Montville wrote. In fact, Eleanor and Lou met at a “free-flowing” party that Babe had hosted in his Chicago hotel suite.9 Not long after the ship-wide search for Eleanor had ended, Ruth knocked on the couple’s door; he wanted to be friends. “But my unforgiving husband turned his back. … Their feud, their ridiculous new feud, didn’t diminish the team’s performance when it came to baseball; we simply went our separate ways.”10 The rift lasted for years, until a dying Gehrig stood for an ovation at Yankee Stadium one final time, on July 4, 1939. Ruth and the Iron Horse embraced in front of 61,808 fans.

The all-stars arrived in Japan none too soon. The major leaguers played 18 exhibition games against Japanese teams, mostly college squads, and trounced the competition by a combined score of 181-36. Ruth gave the competition a so-so rating. “I was surprised by their high-class fielding and the ability of some of their pitchers,” Ruth wrote in his autobiography. “But they couldn’t hit a lick.”11

The final scores didn’t matter. Japanese baseball fans loved Ruth. Of course, they had heard all about the legendary ballplayer. They wanted him to hit home runs. They yelled for their hurlers to throw pitches that Ruth could launch into the sky and circle the bases to even more applause. They shouted, “Banzai Babe Ruth!,” imploring him to live a thousand years, and ran toward the stocky baseball legend. Ruth, of course, loved the attention and waved US and Japanese flags. Nearly a half-million fans watched the action in Tokyo and other cities. The Babe signed autographs, posed for pictures, and earned plenty of laughs. He took exaggerated swings at times and made jokes about the height differences between the smaller Japanese players and himself. Ruth even borrowed an umbrella and held it high while he played first base one soggy day. The crowd loved the Babe’s antics. Ruth loved them back. The players took lots of pictures. Moe Berg, an Ivy League-educated, weak-hitting catcher, took more than the others. He didn’t take many tourist snapshots. He focused on pictures that showed Japanese industrial and military might. “He had been recruited by the OSS (Office of Strategic Services, forerunner of the CIA) as an American spy,” Montville wrote in The Big Bam.12

After the tour, most of the players boarded a ship and made the return trip across the Pacific Ocean. Ruth and his family, along with the Gehrigs and a few other couples, kept trotting the globe. (The Ruths and Gehrigs took different ships. Probably a good idea.) The Ruths stopped off in Java and Bali. Babe didn’t like the women, who chewed a red tobacco that stained their teeth. “They are billed as the most beautiful women in the world,” said Ruth.13 The ship sailed into the Red Sea, through the Suez Canal, and, finally, to the Mediterranean Sea.

The stayover in Paris disheartened Babe. No one knew him. The man who could draw a crowd almost anywhere, who could attract hero worshippers, photographers, and reporters in big cities and small towns, who boasted maybe the most famous face in the world, walked as a stranger in the fabled City of Light, a place he called “not much of a town.”14 No one recognized him as he strolled down the famed Champs-Elysees. Even the American boys living in Paris didn’t play baseball. “Imagine an American kid not knowing how to swing a bat,” Ruth said.15 He probably shuddered at the very idea.

Ruth did talk to one reporter in Paris about his future as a big-league skipper. He probably could have had the Cleveland Indians job or the Red Sox gig. He also mentioned the Athletics and the Braves. “One thing, though, if I can’t manage a club, I’ll quit,” he insisted.16 (Mack already had nixed the idea of hiring Ruth as skipper. It had nothing to do with possible shenanigans between Babe and Eleanor Gehrig, it seems. Mack didn’t like the way Mrs. Ruth ordered her husband around while aboard ship. “If I gave the job to him, she would be managing the team in a month,” Mack said.17 There went that opportunity. (Mack, a part-owner of the Athletics, stayed on as skipper through the 1950 season. He retired at the age of 88.)

Paul Gallico wrote a column on Ruth’s international adventures. He began it by informing his readers, “George Herman Ruth doesn’t like Paris. He does not like the French.” Supposedly, Ruth had “ten-thousand well-chosen words” on why he loathed the place. Gallico did not print the diatribe. He boiled it down to Ruth saying, “I do not think the French care much about baseball,’ and hence, were probably not much concerned about Le Gros Bebe when he was in Paris.”18

Ruth’s mood brightened as he headed to the Swiss Alps and the St. Moritz resort. A reporter asked Babe if he could ski. Well, what a silly question to ask a real-life action figure. “Can I ski?” an incredulous Ruth responded, hardly believing the question. “I’m a champ at that game.” He called his try at bobsledding the “the biggest thrill of his life.”19 Yes, bigger even than smashing three home runs in Game Four of the 1926 World Series or hitting 60 home runs in 1927. “I would like to quote his rich and racy language on that trip, but I cannot,” Gallico wrote. “It seemed that all he could do was hold on, hold his breath and let the world go by.” Moving fast. That’s what Ruth did best. Also, “Babe on skis must have been a magnificent and eye-filling picture.”20

Next stop, London. The Ruths flew across the English Channel, from Le Bourget to Croydon. They spent about 10 days in England. No, Ruth said, he still had no job as a manager. “But I would like one,” he added.21 (Col. Huston had decided, on the advice of his wife, not to buy the Dodgers, thus eliminating another possible managerial gig for Ruth. The Colonel, a gentleman farmer in Georgia, told reporters, “Mrs. Huston spoke her piece. Her tone and manner of saying it implied an indisputable authority.” She said, ‘You are not going to buy any ball club. You are going to stick to your cows.’”22)

Ruth liked London. People there knew him. They ran up to him. They gave him the proper attention that he – The Sultan of Swat – felt he deserved. Like giving him cricket lessons. Babe put on the requisite leg pads and took his swings. He liked the game but not the salary. Top cricket players earned about $40 a week, a paltry sum for a home-run king. Ruth laughed when a few cricketers insisted that top bowlers could throw as hard as major-league pitchers like Walter Johnson, aka “The Big Train.” Babe called that “blame foolishness.” The cricketers said they would ask Harold Larwood, one of the game’s most intimidating bowlers, to come down from his Birmingham home in the English Midlands and throw a few Ruth’s way. The Babe hoped that more scientific instruments might be used, but he was game to get into the box against Larwood. “Anybody who thinks this Larwood fellow throws a faster ball than Walter Johnson used to throw past me can have my money.”23

Alas, the great matchup between cricket bowler and baseball batter never happened. And more’s the pity. Larwood couldn’t make the trip down to London. John Lardner insisted that the sports world missed quite a battle. Lardner called Larwood “one of the most interesting athletes in England.” He liked to bowl inside, dusting off his opponents and keeping them nervous. Hitting a batter is not against the rules in cricket, and Larwood, a part-time miner, bruised plenty of them. In a match against Australia, he hit the opposing batsmen “hard and profusely. He hit nearly all of them, playing no favorites.”24 Maybe Ruth would have taken exception to Larwood’s high, hard ones.

Some cricketers swore that a top batsman could crush a ball 600 feet. Ruth didn’t believe that claim. The Maharajah took a few more swings. “Whack! Whack!” He said, “I wish they would let me use a bat as wide as this in baseball. I’d be good for five more years.”25 Later, while sitting in his pajamas and smoking a cigar at the swanky Savoy Hotel, he answered claims that cricket requires more skill than baseball. Ruth broke into loud laughter. “Skill! A game? Why cricket’s not a game at all. It’s a tea party. It seems to me all they do is hold the bat and let the ball roll against it. Still, I don’t want to criticize. I guess they enjoy it, or they wouldn’t do it so much.”26 The British probably loved that comment.

Ruth played some golf in London and plunked himself in the process. He stood on a rooftop in front of the press corps and teed off a shot into the midtown air, taking aim at the nearby Thames. The ball smacked into a parapet that encircled the roof and ricocheted toward Ruth, thumping him in the chest. The energized drive “nearly went right on through him.”27

Hamilton asked Ruth whether there existed a “yellow peril,” i.e., did Japan pose an imminent threat to the United States. Babe, put into the role of amateur statesman, deflected the question. (“Warlike? Hell, they don’t look warlike.”) Instead, he once again complimented the Japanese for their great love of America’s national pastime. “Man, they’re just crazy about baseball. They play baseball before breakfast!” Ruth said he might yet hit a few more home runs in the big leagues. “But not many, I guess. After all, I’m 40 years old. I can’t expect to play forever.”28 Finally, Ruth spoke to someone on the telephone – a hotel employee? – who assured him that the ballplayer’s packing trunks – which he hadn’t seen since leaving Japan – would be in Southampton before his ship, the Manhattan, left port the next day. “Boy, they better be!” Ruth bellowed.

The Manhattan arrived in New York City on February 20. A band greeted Ruth and serenaded him with a rendition of “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” Babe had traveled more than 21,000 miles in his four-month stay from home. It was the first real vacation he ever had, Claire Ruth said. Babe told the writers “It was great” and “I wouldn’t do it again for $100,000.”29 Ruth played one more year as a player. The Boston Braves had purchased his contract from the Yankees, also naming him “assistant manager” and “vice president.” Ruth smacked six home runs, hit .181 in 72 at-bats, and retired in late May. He never managed a big-league team.

GLEN SPARKS has contributed to several SABR books and is working on a full-length biography of Hall of Fame shortstop Pee Wee Reese. A veteran of the Santa Monica, California, Little League program, he majored in journalism at the University of Missouri and lives in St. Louis with his wife, Pam.

Notes

1 Gayle Talbot (Associated Press), “Babe Busts a Bat Showing English What Is Cricket,” New York Daily News, February 10, 1935: 197.

2 United Press, “Col. Huston Seeks Dodgers and Babe,” Paducah (Kentucky) Sun-Democrat, November 2, 1934: 12.

3 “House of David Offers Babe Ruth $35,000 to Play,” Fresno (California) Bee, November 2, 1934: 21.

4 Babe Ruth and Bob Considine, The Babe Ruth Story (New York: Signet, 1992), 203.

5 Dorothy Ruth Pirone and Chris Martens, My Dad, the Babe (Boston: Quinlan Press, 1988), 113.

6 Leigh Montville, The Big Bam: The Life and Times of Babe Ruth (New York: Doubleday, 2006), 332.

7 Eleanor Gehrig and Joseph Durso, My Luke and I (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1976), 190.

8 Ibid.

9 Montville, 332.

10 Ibid.

11 Ruth and Considine, 203.

12 Montville, 334.

13 Montville, 335.

14 Jane Leavy, The Big Fella: Babe Ruth and the World He Created (New York: HarperCollins, 2018), 414.

15 Robert Creamer, Babe: The Legend Comes to Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1974), 381.

16 Creamer, 381.

17 Montville, 333.

18 Paul Gallico, “The Babe Doesn’t Like Paris,” St Louis Star and Times, February 23, 1935: 7.

19 Creamer, 381.

20 Gallico: 7.

21 Associated Press, “Babe Ruth Flies to London to Celebrate Uncertain Birthday,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 8, 1935: 15.

22 Associated Press, “Mrs. Huston Says ‘No,’ Allentown (Pennsylvania) Morning Call, November 21, 1934: 20.

23 Associated Press, “Babe Ruth Breaks Bat Playing Cricket, Then Stirs Up Controversy,” Calgary (Alberta) Herald, February 12, 1935: 7.

24 John Lardner, “Babe Misses Match with Ace of Cricket,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Journal Star, February 13, 1935: 11.

25 Talbot, “Babe Busts a Bat.”

26 M.H. Hamilton, “Cricket Is No Game, Says Mr. Babe Ruth,” Windsor (Ontario) Star, February 28, 1935: 22.

27 Associated Press, “Golf Ball Nearly Drills Babe Ruth,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 25, 1935: 9.

28 Hamilton.

29 Montville, 336.