Batted Balls and Bayonets: Baseball and The Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914-1918

This article was written by Stephen Dame

This article was published in Our Game, Too: Influential Figures and Milestones in Canadian Baseball (2022)

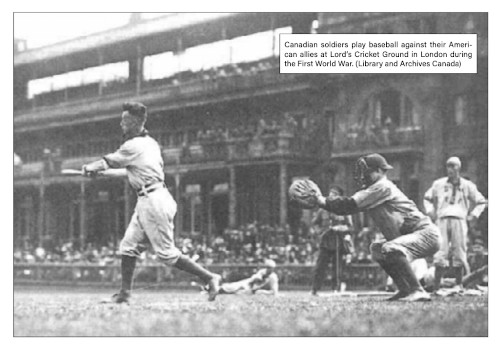

Canadian soldiers play baseball against their American allies at Lord’s Cricket Ground in London during the First World War. (Library and Archives Canada)

Bill Humber, Canada’s foremost baseball historian, has long made the case for baseball’s distinction as Canada’s earliest “national game.” Before indoor rinks and reliable refrigeration, hockey had yet to freeze itself into the collective Canadian consciousness. “If you were to peruse the Canadian newspapers and magazines at the time of Confederation,” he once wrote, “one thing would strike you. There’s no mention of hockey!”1 Yet, since at least the 1830s and probably long before, Canadians had been playing baseball. Bruce Kidd noted that baseball was played “by significant numbers all across Canada,” and was the only game “which drew players and spectators from all classes.”2

When the British Empire put out the call to arms in 1914, more than 60,000 Canadian men signed up within the first few weeks. Even though nearly 70 percent of those citizen soldiers were British-born,3 they had already adopted the ways of their new land, including its love of baseball. During the period immediately before the war “baseball was the game of import in Canada – not the British game of cricket nor the Native Canadian game of Lacrosse.”4

As the volunteers of the Canadian Expeditionary Force suited up and shipped out, they packed their gloves and bats and took their national game with them to war. A total of approximately 600,000 Canadian men entered into military service and baseball proved to be an important part of the First World War experience for many.5

Canadian commanders were not at first convinced that baseball could provide more than just distraction for soldiers at the front. When the first Canadian recruits arrived on the Salisbury Plain in 1914, they were tasked with drills, exercise and discipline. The men bridged the gap between Civvy Street and enlisted life by playing baseball whenever they could.

Canadian officers generally regarded the game as a pursuit that had cathartic qualities, promoted physical and mental fitness, unit cohesion, and sacrifice, and could involve a large number of players simultaneously.6 They discounted, however, the emotional attachment many soldiers had to the game. One member of the 58th Battery Canadian Field Artillery noted that overseeing the training ground, “one can almost picture himself back in Canada watching a lot of kids on the sand lots working out to be big leaguers.”7

Sentimentality aside, sport provided many practical lessons. Sport is often a blunt and honest teacher. Could baseball, with its cruel propensity for failure, prepare soldiers for the agonizing crucible ahead? Craig Greenham, a professor at Wilfrid Laurier University, attempted to explain why baseball seemed well suited to serve as a training ground for war:

“The game provided a chance to cultivate leadership in pressure situations. Baseball allowed for individual responsibility within the framework of a larger cooperative effort as each player/soldier was accountable for his place in the field as well as his turn at the plate. It showed the honour in sacrifice when a batter bunted a ball, giving himself up in the process, to move a runner along the base paths in the name of teamwork and victory. The game encouraged discipline for players who were only to swing at good pitches, but rewarded calculated risks, such as a base runner advancing from first base to third base if the right fielder was known to have a weak arm. Baseball showed its participants how to hold onto an advantage, yet never surrender when behind. Like war itself, baseball had no clock. For both, events continued until finished.”8

By the spring of 1915 the Canadians were spread across England and on the verge of action in Flanders. In order to maintain fighting efficiency, military commanders developed a system in which units rotated regularly between front line, reserve, and rest areas.9 The time between the trenches was a boon for baseballers. Suddenly it was possible to schedule games, and even plan for regular league matches. The Canadian training center at Shorncliffe and the nearby soldier-billeting town of Folkestone soon had a calendar of games for home and away.

Word of wartime baseball spread across the ocean quite quickly. Letters from the front spoke of sandlot games and triumphs on the diamond. Propaganda posters featured military men bettering their soccer, boxing and baseball skills. Even recruiting officers sold potential soldiers on opportunities for nonlethal competition while in khaki. Recruiters spoke of sport days in the military camps during their enlistment rally speeches and assured that there would be plenty of opportunity to play games like baseball for all those who signed up to serve their country.10

Private Nurse, a wounded veteran, joked with a Toronto recruiting rally that “we’ve got a lot of baseball over there and we need pitchers.”11 The audience may have laughed, but Nurse and his government understood the use of baseball as a powerful recruiting tool.

Once overseas, Canadian soldiers held the military to its promise. The Canadian Army Fields Comforts Commission was established to provide soldiers with whatever luxuries the military deemed permissible. From cigarettes to socks, the CFCC was tasked with soliciting requests from soldiers and communicating those desires back to Canada. The commission published a magazine in which soldiers could request items and express their thanks for things received.

The frequency with which baseball equipment was requested by the men in 1915 demonstrated that baseball was already the most popular sport among the Canadian Forces.12 The Shorncliffe base was the first unofficial home of organized Canadian baseball overseas. Locals jokingly referred to the area as a suburb of Toronto. Canadians became a part of local culture. Researchers discovered that local jargon changed to reflect “Canadianisms,” with people saying “sure” when asked questions instead of “yes.”13

One soldier wrote that at Shorncliffe, amid all the uncertainty of war, one thing was always certain: “baseball takes over in the evenings.”14 Baseball was so often showcased before curious English crowds that Canadian soldiers during the Great War were likened to Union and Rebel troops during the US Civil War: “agents of expansion”15 who spread the knowledge and popularity of baseball as they traveled far and wide playing the game.

As the war expanded, more men arrived from Canada. The CFCC was having trouble keeping up with the demand for baseball. They went so far as to put a stop to further sock and wool donations and specifically requested more baseball equipment. Though much was donated, it still wasn’t enough to meet demand. So the CFCC took it upon itself to finance the soldiers’ ball field recreation. At Folkestone, not far from the Shorncliffe base, a Patriotic Tea Room was opened to sell drinks and delicacies to the locals. The proceeds went toward purchasing baseballs, bats, and ball gloves. It argues well for baseball as Canada’s national game that no such tea rooms were established to secure goalie pads or lacrosse sticks. Baseball was top of mind.

Word of the Canadians and their baseball madness spread beyond the pages of the CFCC magazine. The Globe and Mail and New York Times ran stories of sports behind the lines. In May of 1915, Ban Johnson, president of the American League, wired Toronto Mayor Tommy Church and offered to send a “big assortment of baseball paraphernalia” for distribution among the Canadian Forces in France.16

Infamous Minister of Militia Sam Hughes, viewed as an unstable megalomaniac by many, simply a maniac by others,17 was notified of the offer and accepted. Hughes, a supporter of enlisted baseball, received 720 baseballs, 50 bats, 6 sets of catcher equipment, 6 sets of uniforms, and an unknown number of baseball gloves.18 Johnson’s generosity was widely reported and he basked in the positive press. “The American League club owners and players will cheerfully make this contribution,” he told the New York Times.19 Days later, the Times reported that AL players would also sign souvenir baseballs for shipment to the Canadian troops.

The gestures were perhaps not entirely altruistic. Professor Greenham argued that Ban Johnson saw the Canadian soldiers’ embrace of the American game as a furtherance of the earlier Spalding tours, which once sought to popularize baseball around the world. The Canadians’ showcasing of the game was another step toward “exhibiting and spreading baseball as authentic American culture … transform(ing) the sport into a global phenomenon.”20

By the midsummer of 1915, the Canadian troops training in England and fighting in Flanders were so identified with baseball that they began to garner challenges from civilian teams. A group of expatriate United States citizens living and working in London began to formally petition the Canadian command for “friendlies.” Jack Norworth, a comedian and the co-writer of “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” was the honorary sponsor and organizer of these men who called themselves the London Americans.

A game between “Team Canada” (staff and convalescent soldiers from the Epsom military hospital) and “Team USA” (London Americans) took place in June during a military sports festival at Stamford Bridge.21 The enlisted Canadian men defeated the American civilians 10-6. The second game of the series saw the London Americans beat Team Canada 9-7. It was the Canadians, however, who took the rubber match, 15-6.

By the fall of 1915, the hallowed green of Lord’s Cricket Ground was playing host to these international baseball friendlies. This time, a group of soldiers from Shorncliffe wore the title of Team Canada. They beat the London Americans 14-4.

Sam Hughes threw out the first pitch before a team of Canadians from Epsom convincingly defeated a team of “touring American all-stars.”22 In Canada, the minister of the overseas forces, Edward Kemp, authorized financial support for the event, including travel costs for soldiers to attend. The players were winning, the government was paying and perception among the soldiers placed baseball at the top of their recreational pursuits. Besides, Canadian soldiers playing baseball at Lord’s Cricket Ground was, to quote one expert, “a very big deal.”23 It was clear by the end of the first informal military baseball season that a more formally organized league structure, with full government support, would flourish in 1916.

The first formal league was encouraged by the Canadian government but financed and organized by the YMCA. Military hospitals and bases at Orpington, Buxton, Covington, and Epsom were among the first sites for structured league games. Hospitals would field multiple teams and be represented by staff and convalescent soldiers at various positions. This caused their lineups to be more fluid as men were discharged, transferred, or newly arrived.

Other teams were formed out of army divisions, their games scheduled around rotations to and from the front lines. These teams, the Fighting 18th, the Queen’s Own Rifles or the Engineering Training Corps, to name a few, kept and fostered a more permanent lineup of skilled players.

J.G. Lee, an American baseball entrepreneur who had tried to create a British Baseball League before the war, jumped at the opportunity to give the Canadian soldiers a league of their own. Lee negotiated with the Canadian government while also taking control of the London Americans. He created what was a de facto professional baseball league which featured Canadian soldiers being paid by their government and American ex-pats for whom he would foot the bill.

Lee was careful to point out that all proceeds from tickets sold to view games in his league would be donated to causes associated with wounded soldiers. Yet, he hoped the enlisted Canadians would help build a baseball culture in Britain and Europe that he could then exploit for profit after the war. Lee’s Military Baseball League would stage games at the Canadian military hospitals at Taplow, Epsom, Bearwood, and Bushy Park. He also secured the Arsenal football grounds as a neutral location for games.

By 1917, the number of baseball games being played throughout the Canadian Expeditionary Force created a momentum for the sport that could not be stopped.24 Two baseball leagues were in operation concurrently in Britain. J.G. Lee’s league was renamed the Military Hospital Baseball League. Lee organized over 150 games that year, an impressive feat given the other training, recuperative, administrative, and even combat duties expected of his players. The MHBL hosted games at its five original sites, including the Arsenal grounds, while also adding a diamond at Uxbridge.

The second league, called the United Kingdom Hospitals and Units league, featured sponsors such as Massey-Harris and the Astor family. The UKHU featured 13 teams playing a schedule of games stretched over the summer months. The Canadian hospitals at Epsom and Taplow played in both leagues simultaneously. The staff, officers, and soldiers at both sites had long considered themselves to be the elite of CEF baseball. During the early organization of Canadian all-star teams, drawn together to face American squads, men from these two locations dominated the lineups.

The leagues structure of 1917 would give the cocksure soldiers of Epsom and Taplow a chance to finally prove their worth. By September, the Epsom team found itself at the top of the MHBL standings and among the top teams in the UKHU. They played and conquered the hospital team at Whitley, which featured Lou Grove as a pitcher. Grove, a standout with the Toronto Maple Leafs baseball club when he signed up for service, was billed as the “best pitcher in the world.”25 With these achievements secured, the boys at Epsom declared themselves champions of the Canadian Overseas Forces in England.

On September 1, 1917, Epsom was invited to play against the Canadian Forestry Corps. The Corps consisted of Canadian bushmen and lumberjacks who had been massed in Europe to fell trees and cut the lumber needed for rail lines, gun stocks, corduroy roads, and other wooden necessities of war. The Royal Family donated Windsor Great Park to the Corps for the duration of the conflict. There, literally in the shadow of Windsor Castle, they lived, trained, and played baseball.

The men of the Corps were tough, competitive troops. Epsom had its own reputation to protect. The game, witnessed by Princess Mary, was said to have been a combative, hard-fought affair. The Corps beat Epsom 1-0. Her Royal Highness, so impressed with what she had seen, invited members of her family along to enjoy the Corps’ next contest. So, on September 7, the vaunted “Forestry Game” was played. The Forestry Corps beat Orpington Hospital 2-1. But it was the peanut gallery that stole the show.

Thousands of spectators packed the grounds. In attendance was again Princess Mary. Beside her sat Princess Helena Victoria, General McDougall, Lady Perley, wife of the high commissioner for Canada, and in specially covered seats near the Canadian dugout: the King and Queen of the British Empire. King George informed General McDougall that he had enjoyed the game and had been impressed with the enthusiasm the Canadians exhibited.26 The soldiers were undoubtedly honored to play before their Head of State and the man for whom they rallied to “King and Country.”

Yet, it was Princess Patricia, known then as the prettiest of the royal family, whom soldiers clamored to glimpse at during the ballgame. Patricia was already iconic in Canada. She had lived in Ottawa while her father was governor general. By 1917 she not only adorned the name of a military regiment based in Edmonton, but was also pictured on the one dollar bill. Patricia “truly enjoyed baseball more than any other royal with the exception of the king.”27 She volunteered at the Canadian hospital at Orpington and regularly attended baseball games there.

A photo of what became known as “The Forestry Game,” held in the collection of Library and Archives Canada and colorized by the Vimy Foundation for its 2018 book They Fought in Colour,28 clearly shows Charlie Kelly, a Black man, at bat for the Forestry side. It stands as evidence that desegregated baseball was taking place in the Canadian Expeditionary Force in 1917.

Special occasions and holidays warranted highly touted baseball games. On July 1, 1917, Canada marked 50 years since its political confederation. Celebrations at home were subdued due to the war. In fact, a national celebration of Dominion Day, as July 1 was then called, wouldn’t occur in Ottawa until 1927, when the country marked its diamond jubilee. Overseas, however, the event was commemorated with baseball games. Special Dominion Day games were played at Cliveden and Ramsgate.

The anniversary was also marked on two separate July occasions with international matches at Lord’s Cricket Grounds. A July 2 crowd of 10,000 saw the Canadian Pay Records team (billed as Team Canada) defeat the London Americans (billed as Team USA) by a score of 7-3. On July 28 Canada (Taplow hospital) defeated Team USA (London Americans) 12-3. The Canadian successes on the diamond, the soldiers’ appetite for baseball as their primary form of recreation, and the arrival of American troops with whom to compete, forced the government’s hand in the fall of 1917.

By January of 1918, the Canadian government had stopped outsourcing their troops’ baseball fix. The Canadian Military Athletic Association was formed. From that point onward, baseball was a fully funded and officially organized and sanctioned division of the Dominion government and its war effort.

Professor Greenham provides the most succinct and eloquent description of the CMAA:

“The Canadian Military Athletic Association stated that its mandate was to inaugurate athletics and competition between Canadian units in Great Britain, as well as standardize athletic contests of all kinds. Baseball, boxing, soccer and athletics were overseen by the CMAA. All the local games were reported to the national office, which not only recorded outcomes but appointed umpires. The national office also provided prizes and arranged intra-area playoff matches which would crown a national champion.”29

The CMAA was financed via a one-pound sterling fee collected quarterly from each unit. The more formal recognition of the CMAA system gave teams like Epsom the opportunity to back up their bluster. Epsom had long claimed to be the best baseball team on offer, and now they would have a chance to prove it. The CMAA season began with exhibition games between Canadian and American all-star teams in Swansea and Reading. Over 10,000 people witnessed each game. When the regular season began in May 1918, the CMAA boasted 14 teams playing 250 scheduled games at six locations. Both the Arsenal grounds and the stadium at Stamford Bridge hosted games. Some league teams, like the 2nd Canadian division, played so many additional challenge and exhibition matches that they claimed to have played 300 baseball games in May alone. Baseball was being played significantly more than any other sport.30

By the time the season ended, Epsom did indeed find itself in the championship final. Epsom was then beaten by the Canadian Engineers Training Corps. The engineers took the title via an unknown score before a large, mixed crowd of soldiers and curious locals. The engineers took their Canadian title into battle against the American champs, the US Regimental 9. In what can be considered the first military World Series, the Canadian side won, 8-2. Film footage of the game survives on YouTube.31

The arrival of the United States on the side of the Triple Entente radically altered the trajectory of both the war and its ancillary baseball games. Many major leaguers volunteered, among them Branch Rickey, Christy Mathewson, and Ty Cobb. These men were asked to join teams but all demurred for fear of the “slacker” label. The summer of 1918, with the Doughboys now playing baseball in uniform, saw an ever greater presence of organized leagues for soldiers. Canadian and American troops played in the CMMA baseball league, a Southeast Military Bases League, and even a league organized around Paris once it became safe enough to do so. But no organization ever came so close to supplanting major-league baseball as the center of the baseball world than the Anglo-American Baseball League.

The AABL was the brainchild of American entrepreneurs Howard Booker and W.A. Parsons, and ballplayer Arlie Latham. Recognizing the Canadians as pioneers and missionaries of the sport during the early days of the war, they saw the potential for a professional league in Britain. With American and Canadian troops arriving by the literal boatload, major leaguers like Hugh Miller and Mike McNally willing to play, and names like Rickey, Mathewson, and Cobb creating a baseball buzz behind the lines, the infield soil had never been so fertile.

The AABL created two divisions, Canadian and American, and scheduled at least 150 games to be played at seven sites with two teams sharing use of the Arsenal grounds. The Canadian division consisted of the hospital teams at Epsom and Sunningdale and administrative teams from the pay and records offices. The American division featured teams from the US Navy, US Army, Hounslow barracks, and Northolt aviation camp. The arrival of overwhelming numbers of American players ended the Canadian dominance of First World War baseball. Only Epsom sported a winning record at the end of the AABL season.

The US Army team claimed the championship, but it was their July 4, 1918, match against Navy that dominates American lore. The match was held at Stamford Bridge before 38,000 spectators. The crowd included a man who had been introduced to the game by the play of hard-scrabble Canadians: King George V.

Aside from league play in Britain, Canadians played baseball informally in France, Belgium, both sides of Ireland, Wales, Scotland, and even Salonika, Greece. Future Canadian Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson played games for the Bramshott team in England, recalling his home run there as one of his most enduring Great War memories.32 Wherever the Canadians were stationed, they played baseball. The soldiers themselves believed that top-class baseball had been transferred33 from Flatbush and the Bronx to Flanders and Bovington.

The Canadian Expeditionary Force played baseball at close to 90 international points of interest, over 50 of which were home to organized league or government sponsored games. These CEF baseball locations are pinpointed on an interactive digital map created by the author. The map may be accessed at hipmuseum.com/greatwarbaseball.

The high point for Canadian baseball during the First World War occurred on July 1, 1918, in Tincques, France. There, the Canadian Corps organized a sports day. The Corps was in its glory, Vimy and Hill 70 had been won, and the Canadians would soon be in the midst of the fabled “Last 100 Days” victories over Germany. Morale was high. The end of the war seemed near.

A reported 70,000 people packed a specially constructed stadium to watch the championships of many track and field events. The baseball final was the main event. It was scheduled last, after tea, for 4:15 P.M. in the large stadium. The soccer final, scheduled for the same time, was held in a small field without grandstands.

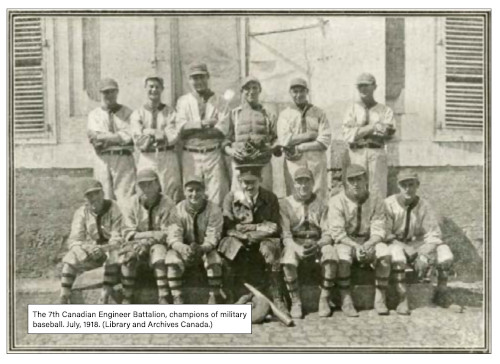

The baseball game was reportedly a classic, as tight, low-scoring affairs were considered the best type of baseball at the time. The 7th Engineer Battalion, consisting of Vimy veterans from various provinces, defeated the 1st Divisional Ammunition Column, an Ontario regiment that once included John McCrae, author of the famed war memorial poem “In Flanders Fields,” by a score of 3-2 in 11 innings. Prime Minister Robert Borden and Lieutenant General Arthur Currie watched the game in person. Famed Indigenous athlete and soldier Tom Longboat had won the eight-mile running race earlier in the day, and may have been among those soldiers watching the game.

The placement of baseball in the schedule of events supports the idea that the game was valued as the top form of recreation by the soldiers and officers who played it. Canadian men loved their national game. The commanders who encouraged baseball play had come to recognize it as not only valuable physical activity, but also as a comfort against the horrors of war, a powerful tool against idleness and boredom and a reminder of more peaceful times back home. Baseball had come to be seen as an essential part of Canadian military life during the Great War.

The official expression of the Government of Canada’s support for baseball was first seen in the December 1917 Guide to Military Sports and Recreation Training. The Guide specified that baseball was a game well suited to building better soldiers. It encouraged soldiers and officers to play together. The government authors of the guide rationalized sport in military terms. They praised its incorporation of muscular Christian ideals. They claimed that the participation of officers would ensure that baseball matches took place with “the true sporting spirit” and would thereby encourage esprit de corps through the promotion of self-sacrifice.34 The volume of games in the thousands per year, the organization of official leagues, the funding of tournaments, stadiums, and transportation coupled with the presence at matches of generals, ministers, the prime minister and His Majesty, all attest to the status afforded Canadian baseball during the conflict.

The 7th Canadian Engineer Battalion, champions of military baseball. July, 1918. (Library and Archives Canada.)

The greatest endorsement of the game may be its consistent reference within regimental diaries. The diaries were permanent records of daily wartime experience. Entries were written by a commanding officer, usually at the end of a day if circumstances permitted. Two of the diaries survived intact and are now digitized. They provide us with the best glimpse into the soldiers’ perspective on baseball. They reveal also that games, particularly if the pennant was on the line, were fiercely waged. Baseball still mattered to these troops. The game’s significance did not diminish during wartime.35

The diary of the Toronto-based Queen’s Own Rifles mentions 68 different baseball games played throughout Flanders. Baseball is mentioned more than any other sport and is third only to references of battle and training. The diary details a game which was played at Bois de Froissart, France, during the preparations for the attack on Hill 70. The diary notes that soldiers were looking forward to the game, largely due to the fact that it was an “officers vs. men” affair. The men won, by a score of 26-3.36 After a multi-sentence entry about a baseball game, the diary then states simply, “the German offensive continues.”

The diary of the 18th Battalion, a group of soldiers from Western Ontario, contains a typical sketch of boys at play when it is interrupted by the reality of war. During a game played behind the lines, a stray bullet from a nearby rifle range found its way onto the diamond. A military transport driver named Mills was hit and killed. The diary records that “owing to a very unfortunate incident [the team] went right off their game and lost.” The diary scribe goes on to say “this accident naturally spoiled the game.”37

When the war ended, the Canadian government faced two major problems: the lack of discipline from men who were less willing to submit to military drill, and the long period of time it took to transport these men home. Such idle men could of course be pacified with baseball. Matchups were organized and a 1919 Inter-Allied Games, quasi-Olympics featuring baseball, was held for impatient soldiers still stuck in Europe. When it was finally time to go home, Canadian soldiers were discharged near Kinmel Park close to the River Dee.

The Kinmel Park Canadian Athletic Association organized a series of baseball games. Men passing through Kinmel were encouraged to play one last game before heading home. Canada’s First World War baseball story, which began on the Salisbury Plain in 1914, ended at Kinmel Park in 1919. For many Canadians, their last act as a soldier was stepping up to the plate in a military baseball game.

For many of the rank-and-file, baseball was vital to their Great War experience. “From the moment our men get out of the trenches,” remarked Lieutenant Coningsby Dawson, “they begin to play baseball.”38 For enlisted men, the game eased the burden of homesickness, because it allowed them to recall the pleasanter circumstances of normal existence.39 For officers, the game provided a wholesome and worthwhile alternative to the unsavory temptations that awaited idle soldiers.

Many officers saw the physical, mental, and emotional benefits that the game brought their troops and incorporated it into their routines, even using it as a recruitment tool.40 As the casualty lists lengthened, fewer Canadians saw war as a game.41 Baseball was the necessary salve for men being introduced to the horrors of the First World War. Baseball’s ability to recall Canada, home, and peace comforted men while its expressions gave them a vocabulary with which to express and suppress their experiences at the front. Canadians played other sports, but none so often as baseball.42

The presence of the game at hospitals and convalescent homes cannot be overlooked. Baseball served a purpose during the war. An American pitcher, soldier Leon Vannais, wrote home to his mother in Hartford, Connecticut. Commenting on a game between his US squad and Canadian soldiers, Vannais touched upon the higher calling for Great War ballplayers:

“The side lines were as noisy as the bleachers of home – the cheers will be for our opponents (the Canadians) and the jeers will be for us; yet we’re happier that way for the fans are the wounded. Mother, you can’t conceive of how wonderful they are! Bright blue suits, bright red ties, clean white bandages, many slings, numerous crutches; if it were not for the faces, one would weep to look at them. But one has no desire to feel sad except in a sub-conscious way. The cheerfulness of the wounded men is contagious. They sit there – their eyes sparkling with mirth and interest – their shouts full of the old familiar rooting expressions made wonderfully fresh and greatly supplemented by their witty mixing in of the new slang of war. No wonder we don’t mind who they cheered for, it’s enough that we’re able to give them an afternoon of real sport.”43

If the clichés about Canada and the First World War are true, if this was indeed Canada’s “coming of age” and “baptism by fire,” then it must be noted that she came of age playing her national game: baseball.

STEPHEN DAME is a middle school teacher of Humanities in Toronto. He is a member of the Hanlan’s Point chapter of SABR. Stephen regularly presents research papers at the annual conference organized by the Centre for Canadian Baseball Research. He has researched military baseball during Canada’s World War efforts, and explored the links between baseball and the prime ministers of Canada.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Andrew Horrall, Craig Greenham, and Jim Leeke for their incredible and invaluable resources. All three men were also very kind to put up with, and respond to, pestering digital correspondences. This project stands on the significant foundation they laid.

Notes

1 William Humber, “What Was Early Canadian Hockey and What Does It Owe to Others?” Research paper, Seneca College, 2017:1.

2 Bruce Kidd, The Struggle for Canadian Sport (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2017), 24.

3 Chris Sharpe, “Enlistment in the Canadian Expeditionary Force,” Canadian Military History 24, no. 2 (2015): 19.

4 Craig Greenham, “On the Battlefront,” American Review of Canadian Studies 42, no.1 (March 2012): 3.

5 Greenham: 1.

6 Greenham: 2.

7 Andrew Horrall, “‘Keep-A-Fighting! Play the Game!’ Baseball and the Canadian Forces During the First World War,” Canadian Military History 10, no.2 (2001): 4

8 Greenham: 4.

9 Horrall: 4.

10 Greenham: 4.

11 Horrall: 4.

12 Horrall: 5.

13 Mark MacKinnon, “We’ll Take Care of Your Boys Forever,” Globe and Mail, April 17, 2015: F1.

14 Anonymous Correspondent, “Work and Play Well Mixed,” Tank Tatler, October 1918: 12.

15 Greenham: 5.

16 Horrall: 4.

17 Tim Cook, Warlords: Borden, Mackenzie King, and Canada’s World Wars (Toronto: Penguin Group, 2013), 37.

18 Jim Leeke, Nine Innings for the King (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2015), 16.

19 Leeke, 16.

20 Craig Greenham, “On the Battlefront,” American Review of Canadian Studies 42, no.1 (March 2012): 6.

21 Leeke, Nine Innings for the King, 16.

22 Horrall: 5.

23 Leeke, 16.

24 Horrall: 6.

25 Horrall: 8.

26 Leeke, 24.

27 Leeke, 54.

28 The Vimy Foundation, They Fought in Colour (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2018).

29 Greenham: 10.

30 Horrall: 10.

31 “Americans v. Canadians – Baseball (1916-1918),” Youtube.com, last modified April 13, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r84a8yYxWhE.

32 Lester B. Pearson, Memoirs of the Right Honourable Lester Pearson. Vol 1. 1972 Page 40

33 Horrall: 8.

34 Horrall: 8.

35 Greenham: 13.

36 “Queen’s Own Rifles Museum,” World War I resources, last modified June 30, 2019, https://qormuseum.org/.

37 “Canadian Great War Project,” Private John Cushnie collection, last modified January 10, 2013, http://www.canadiangreatwarproject.com/transcripts/cushnie191806.asp.

38 Greenham: 1.

39 Greenham: 10.

40 Greenham: 10.

41 Horrall: 5.

42 Horrall: 12.

43 Leeke, 23.