Black Baseball in the Maritimes: 1880-1980

This article was written by Colin Howell

This article was published in Our Game, Too: Influential Figures and Milestones in Canadian Baseball (2022)

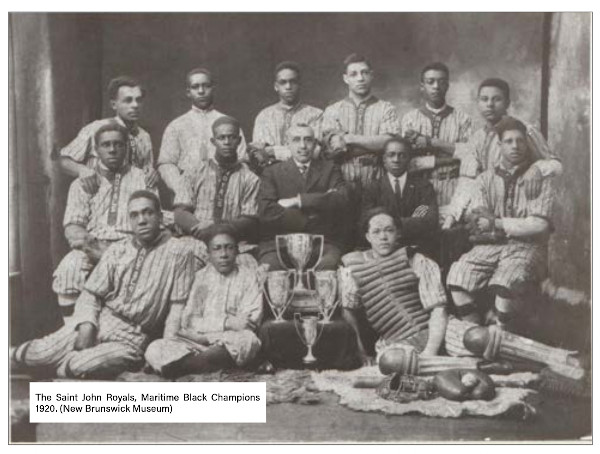

The Saint John Royals, Maritime Black Champions 1920. (New Brunswick Museum)

Although the origins of Black baseball in the Maritimes remain obscure, it is likely that the game was being played informally as early as the 1870s. Operating independently, but often in association with the African Baptist and Episcopal churches, black teams like the Eurekas, Victorias, and North-Ends of Halifax, the Dartmouth Stanleys, Truro Victorias, Amherst Royals, Woodstock Wanderers, Fredericton Celestials, and the Royals and Ralph Waldo Emersons in Saint John appeared in growing numbers in the following decade.

These clubs were increasingly well-known by 1890, playing challenge matches for money prizes usually arranged through notices in local newspapers. Standout players like Joe Eatman, “crack catcher” of the Celestials, and Truro’s hard throwing Vickery, who Eatman said “could throw a curve around a baseball,” received accolades in the daily press. According to the Fredericton Gleaner on June 11, 1890, “it was worth walking some distance to see the playing of Joe Eatman alone.”1

As challenges involving various teams increased, an annual Maritime Black Baseball championship was organized in the early 1890s – at the very least by 1894 – more than a year before the now well-known Nova Scotia Colored Hockey League began operations in 1895. Many ballplayers were also stars on the ice, including shortstop Eddie Martin of the Halifax Eurekas, who is credited with the introduction of hockey’s slap shot to his Colored Hockey League club. Indeed, the development of Black hockey occurred on a solid foundation of inter-community and intra-regional competition already in place in baseball. The Eurekas won seven of eight Maritime baseball championships between 1894 and 1902.2

There were a number of prominent families involved in the early days of Black baseball in the Maritimes. The O’Rees, McIntyres, Gordons, and Eatmans in Fredericton, the Hectors, Skinners, and Washingtons in Saint John, the Dorringtons, Mentises, and Maxwells in Truro, and the Paris family in Westville, Halifax, and Three Miles Plains, were among the most acknowledged. Recent essays by historian Roger Nason and journalist Greg Mercer offer a detailed look at team rosters and lineups in New Brunswick, including those of the Saint John Resolutes and Alerts in 1886. The Alerts had four members of the Hector family in their lineup, led by curveball specialist Jamie “Jumbo” Hector, while Ned and Bob Washington anchored the Resolutes squad.

The latters’ father, Thomas C. Washington, whose restaurant and saloon catered to sportsmen of various kinds, including cricketers and ballplayers, was an active promoter of sport and other forms of entertainment. In 1889 Thomas Washington was instrumental in the formation of the Saint John Royals, who won two games against a visiting Halifax club that year playing before an estimated crowd of 1,500. Beginning in 1905, under the leadership of coach and captain A.H. Skinner, the Royals began a dominant run as Maritime champions. Like the Eurekas before them, they were the team to beat in the years before World War I.3

Although regional baseball competition was interrupted by the war, it returned in earnest after that in response to a pent-up desire for pleasurable entertainment. Earlier, Black teams had only played each other, but by the 1920s there were occasional but increasingly frequent games between White and Black clubs. In 1921, for example, the Halifax Coloured Diamonds, winner of the provincial Black championship that year, drew over 6,000 spectators during a two-game series against a White all-star team from the city. Not surprisingly, the success of the Coloured Diamonds came to the attention of their New Brunswick counterparts.

The Halifax Herald of June 7, 1922, reported that the Saint John Royals wanted to revive the Maritime championship: “G.E. Hope, business manager of the [Saint John] Colored Athletic Association … writes that his club is after games in Halifax with the Diamonds or any other colored team. The Saint John players are willing to meet in home and home games for the Maritime title.”4

By that time the Royals were also interested in playing against barnstorming teams from the United States for a shared portion of the gate. One of those series took place that same season when the Royals upset the touring Detroit Clowns. Over the next three decades, the Clowns were frequent visitors to the Maritimes, their final visit taking place in 1949.

Dressed in clown outfits and promising a circus-like atmosphere, the Detroit tourists had come to town that first time expecting to win handily, but lost two of three games to the Royals. Royals pitcher Fred Diggs, a rubber-armed fastballer, held the Clowns in check, while batterymate Ace Austin and first baseman Kid Tynes led the offense.5

This series was but one of many against barnstorming Black teams in the interwar period. The Cleveland Colored Giants, New York’s Black Yankees and Colored Giants, Chappie Johnson’s Philadelphia All-Stars, the Broadway Stars, the Philadelphia Stars, the Zulu Cannibal Giants, the Ethiopian Clowns (earlier known as the Miami Clowns), the Black House of David, and even a team of Hawaiian players of Japanese descent — referred to derisively in the press as “the Japs” — helped turn the Maritimes into a baseball burned-over district over the years.

In turn they exposed regional audiences to the exploits of great Negro League players like Newton Joseph of the Kansas City Monarchs, infielder Billy Yancey of the New York Lincolns and a number of other clubs, and Gus Gadsden and Judy Johnson of the famous Hilldale club. Two players in particular, catcher Burlin White and his batterymate, Bill “Cannonball” Jackman, a lanky submarine stylist, became household names. For a few years White and Jackman toured together, but when White established the Boston Royal Giants in 1932, Jackman headed up the Philadelphia Giants and toured New Brunswick and Cape Breton for a series against the Broadway Stars, and against town teams along the way.

Traveling throughout the Maritimes, White and the Giants kept an eye out for local Black players who might be interested in touring with the club for a couple of weeks and filling in when required. In interwar Truro and Yarmouth, Blacks and Whites often played together on local diamonds. The Truro Sheiks, a Black club that became a mainstay of the local sporting scene for decades, often had White players in their lineup, while Yarmouth’s Gateways occasionally had Black players in their regular batting order.

In addition, Yarmouth fielded an all-Black team that played a regular schedule in the Yarmouth town league in the 1930s, a precursor of the predominantly Black Yarmouth Novies of the postwar era. In New Glasgow, the Coloured Wonders began playing White teams as a member of the Pictou County League in 1932, and young Black stars like slugging catcher Freeman Paris, second baseman Ernest Dorrington, and outfielder Alvin McLean were given the chance to play on New Glasgow’s all-White town team a couple of years later.

After a game in Truro in June 1935 involving what the Halifax Herald called “a mixture of white and coloured boys” – most likely the Sheiks – White spoke highly of Gordon Maxwell and center fielder Bob Mentis. A former high-school track star and hockey player who some thought was the finest player in the country outside the NHL, Mentis agreed to accompany the Giants as they completed their tour of the province that year. So did Morton “Bucky” Berry, a young pitcher-outfielder from Yarmouth who joined the Giants for six games in 1937, going 6-for-25 at the plate and sparkling defensively.6

White’s Royal Giants played more than 100 games in the Maritimes between 1932 and their final tour in 1939, often incorporating clowning routines to attract large crowds. Well-known performer King Tut, whose real name was Richard King, took the field with a glove twice normal size and a hat with an oversized brim; George “Whitey” Michaels delighted fans catching balls between his legs and behind his back; squeaky-voiced Stormy Faulk pestered umpires and visiting players with his constant chatter and spontaneous comedy; and White sat behind the plate in a rocking chair while throwing baserunners out at second.

Occasionally local players were put off by the clowning. “Comedy would put off my pitching,” Liverpool pitcher Laurie Thorburn claimed. White would “hold the bat, and instead of tryin’ to hit with it … would just point it towards the ball. It looked like he was trying to show me up. Once, I threw a close ball to him to see what he was doin’, and I split his finger right in two.”7 White missed most of the month in the Royals 1936 tour as a result.

Thorburn’s comments aside, the talented Royal Giants were highly respected by ballplayers and fans alike. Busky Johnson was the club’s slick-fielding second baseman, and Blacky McKnight, an outfielder with prodigious power, played alongside speedy center fielder Vince Coleman. William “Babe” Robinson, who replaced Bill Jackman as the club’s pitching ace, could throw sharp breaking curveballs until his arm fell off.

During the 1935 tour, for example, Robinson pitched a complete-game victory over the regional champion St. Stephen club early in the day, hopped in a car for a four-hour trip to Cape Breton, and then defeated a team from the Cape Breton Colliery League that evening. The Giants roster would at times include shortstop Mapp, outfielders Barry and Stevens, and third baseman James.

Local clubs respected the talents of White and his teammates, having learned much from them about the game over the years. In turn, White found the St. Stephen Kiwanis, Liverpool Larrupers, and Yarmouth Gateways worthy opponents. In the early ’30s, the Giants would often spend a week or so along Nova Scotia’s South Shore, schooling local players in the finer points of the game.

In a game against Danny Seaman’s Liverpool club in August of 1935, Seaman scored the winning run in the bottom of the ninth by kicking the ball out of White’s hand as White attempted to tag him. “We wanted to help you,” White said after the game, “but not to have you beat us with our own tactics.”8

The Halifax Herald on May 19, 1936, announced the impending return of the Royal Giants, and upcoming games against Halifax, Liverpool, and the Yarmouth Gateways. The article testified to their mentorship, and pointed out how the visitors “helped open fans’ and players’ eyes to snappy ball.”9 The Yarmouth Gateways “learned a new bag of tricks that helped them in the playoffs” on their way to capturing the 1935 Maritime championship.10

The year before, St. Stephen had split two-game series with both the Royal Giants and Jackman’s Philadelphia Colored Giants. By the time of the Royal Giants’ final tour in 1939, a number of clubs could play them on equal terms. In their final game of that tour, they were held in check by the region’s premier left-hander, Cecil Brownell, losing 5-3 to St. Stephen on their way back to Boston. In the early 1950s the Liverpool Larrupers would honor White and the Royal Giants’ contribution to baseball in the province. White appeared in uniform and made a couple of plate appearances that day.

World War II brought different opportunities for Black players playing on Army and Navy teams around the region, in the newly formed Halifax Defense League (HDL) and in military leagues in Britain, where Canadians and Americans sometimes competed against each other. One of the starriest players in the HDL was Manny McIntyre, a native of Devon, New Brunswick, who hit .385 as the league’s all-star shortstop, and was voted the “most popular player” in 1944 while playing with Halifax Shipyards.11

In 1945, while playing for Trois-Rivières of the Quebec Provincial League, McIntyre came to the attention of the New York Cuban Giants and appeared in a season-ending exhibition game with Negro Leaguers at Yankee Stadium. Despite their interest in Manny, he chose to stay in Canada to play, even after being contacted a second time by the same Negro League club when their Minnie Miñoso signed a contract with the Chicago White Sox.

In addition to McIntyre, Fred Thomas from Windsor, Ontario — one of Canada’s finest athletes in the first half of the twentieth century — played outstanding ball for Halifax Air Force in 1944. Cape Bretoner Charlie Pyle, a speedy outfielder and, like Thomas, a multisport athlete, had a sensational year in the Canadian Army England Baseball League in 1945, finishing second with a .432 batting average. Pyle also competed in track and field, boxing, and softball, and was voted the best all-around athlete in the Canadian Army that year.

Pyle’s fellow Cape Bretoner, Oscar Seale, was equally accomplished, finishing third in the import-laden Cape Breton Colliery League in 1949 with a .350 average. Seale was also an excellent softball player, at one point turning down an offer to tour with Eddie Feigner’s King and His Court four-man team.12

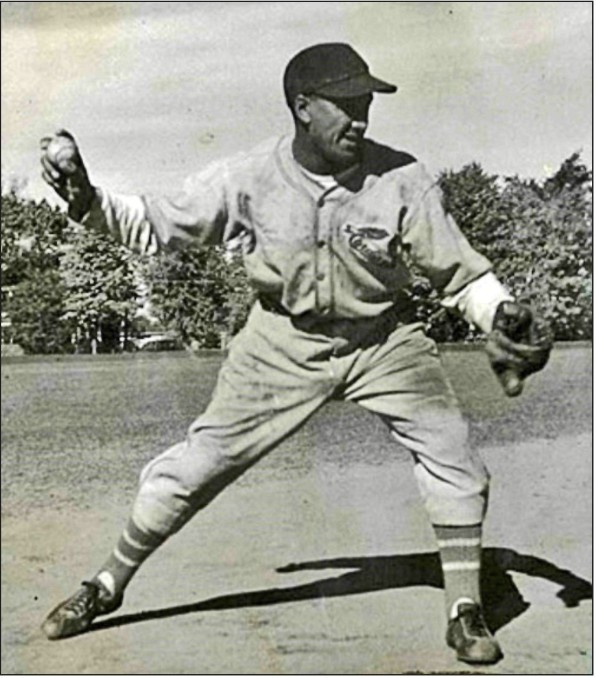

Manny McIntyre of the Middleton Cardinals, 1946 Nova Scotia Senior Championship finalists. (Courtesy daughter Marlene McIntyre, Canadiac, Quebec).

McIntyre and Thomas contributed as well to what historian Jules Tygiel called “baseball’s great experiment,” the gradual desegregation of baseball that followed Jackie Robinson’s breaking of the color bar. When McIntyre signed a contract with Sherbrooke of the Class-C Border League in June 1946, he became the first Black Canadian to play in Organized Baseball after World War II. Two years later Thomas signed a Cleveland Indians contract, and broke the color bar in the Eastern League.

Given their ability in other sports, neither was particularly interested in concentrating on pro baseball careers. McIntyre was a member of the first all-Black line in professional hockey, and even played in Europe for hotelier Charles Ritz’s Paris Racing Club, while Thomas played for the Harlem Globetrotters in basketball, and with the Toronto Argonauts of the Canadian Football league. In the summers both continued to play semipro ball in Quebec, Ontario, and the Maritimes.

In the late 1940s and into the ’50s, a number of other Black players flirted with baseball in the summers while concentrating on professional hockey careers. Art Dorrington made history in 1950 when he became the first Black hockey player to sign an NHL contract, with the New York Rangers organization, but despite five productive years in the Eastern Hockey League he was never given a chance to play in the NHL.

Dorrington was an excellent baseball player as well, breaking in with his hometown Truro Bearcats as a teenager in 1948 at a time when baseball in the region was turning increasingly to imported players. Playing with Saint John of the New Brunswick League in 1949, the speedy outfielder hit .296, outperforming many of the American players who would later play in the major leagues.

After the 1950-51 hockey season, the Boston Braves convinced him to give pro baseball a try, and assigned him to their Wellsville affiliate in the PONY (Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York) League. He showed some power, hitting three home runs in 43 at-bats, but the hockey season had taken its toll, and he ended up in the hospital with pneumonia. After his hockey career ended in 1957, Dorrington took up baseball once more, playing for Hall of Famer Pop Lloyd’s Hap Farley All-Stars in Atlantic City, a successor of the Johnson All-Stars owned by Enoch “Nucky” Johnson, a real-life character made famous by the HBO Boardwalk Empire series.13

Two other players of that era, Truro’s Stan “Chook” Maxwell and Fredericton’s Willie O’Ree, had professional baseball skills but eventually chose to concentrate on their hockey careers. As a 19-year-old, Maxwell broke into the import-laden H&D League with the Truro Bearcats, leading the club with a .283 average, finishing ahead of future major leaguer Grover “Deacon” Jones and two First Team All-Americans from the University of Michigan, Ken Tippery and Bruce Haynam. (Along with Maxwell and Jones, a dozen or so Black players played in the Maritimes during the ’50s, including future major leaguers Don “Chook” Eaddy and Dave Ricketts.)

Braves scout Jeff Jones tried unsuccessfully to sign both Eaddy and Ricketts. For Chook a requirement of playing winter ball in the Caribbean was a deal-breaker because it interfered with his pro hockey aspirations. That same year another young Black player, Halifax Citadels second baseman Billy Carter, finished second on the club in batting, behind Zeke Bella and ahead of double-play partner Tommy Carroll, both of whom went on to play in the majors for the Yankees.14

At about the same time, teenager Willie O’Ree was playing baseball in Fredericton, and accepted an invitation to spring training with the Braves in Waycross, Georgia, in 1956. Appalled by the racist environment in the South, Willie decided at that point to concentrate on hockey, and became the first Black player in the NHL, with the Boston Bruins in 1958.

Another Truro native, Johnny Mentis, turned down offers to play baseball in the States, but became a well-known figure in Quebec baseball and hockey in the 1960s, making history as the first Black hockey player to play against the Russians. Author Merritt Clifton, who wrote a history of the Quebec Provincial League, featured Johnny as one of the top five performers of the ’50s and ’60s in Quebec baseball. According to Clifton, Mentis, in a career that spanned over a dozen years, still holds the highest career batting average of any player in the Provincial League, with more than 1,000 at-bats.15 Johnny’s brothers Burton, Ray, and Bob “Cook” Mentis were fine players as well. Burton played with a predominantly Black team in Halifax, the Vaughan Furriers, who captured the Maritime Junior championship in 1962, and starred in senior ball after that.16

In the changing racial environment after that, all-Black teams in the Maritimes were a rarity; Black players played instead on seniorleague clubs throughout the region. A few, such as Curtis Falls and Curt Coward, played briefly in the minor leagues. By this point, however, other sports — hockey, football, and softball in particular — offered more attractive professional opportunities.

Outfielder Ken Walcott grew up playing baseball in Cape Breton, starred in senior ball for a number of summers, and was eventually selected by Baseball Nova Scotia on its all-star “team of the century” in 2005. Walcott ended up playing three years in the Canadian Football League rather than pursuing a baseball career. In addition, Mark Smith, who had a tryout with the Kansas City Royals in 1982, became one of the world’s finest softball pitchers, and a five-time all-world selection at the ISC world championship as a member of Team Canada.

DR. COLIN HOWELL (B.A., M.A. Dalhousie, PhD, Cincinnati) is professor emeritus in history, recently retired academic director of the Centre for the Study of Sport and Health at Saint Mary’s University, and a former co-editor of the Canadian Historical Review. He has published widely in the field of sport and health studies, and is the author of Northern Sandlots (1995), Blood, Sweat and Cheers: Sport and the Making of Modern Canada (2001), and a number of edited collections.

Notes

1 Quoted in Roger Nason, “Early Black Baseball Teams in Fredericton: A Sign of Community Identity, 1889-1906.” Active History, February 22, 2021. See also, Colin D. Howell, Northern Sandlots: A Social History of Maritime Baseball (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995), 179-80, 274.

2 George Fosty and Darril Fosty, “Colored Hockey League,” Canadian Encyclopedia. https://thecanadi-anencyclopedia.ca/en/article/coloured-hockey-league (accessed October 12, 2021).

3 Roger Nason, “A Lost Chapter in the History of Black Baseball in New Brunswick,” Active History, January 25, 2021; Howell, 179.

4 Halifax Herald, June 7, 1922: 9.

5 Greg Mercer, “How an East Coast all-Black Baseball Team Brought Pride to Their Neighbourhoods,” Globe and Mail, February 27, 2021.

6 Howell, 171-6.

7 Quoted in Robert Ashe, Even the Babe Came to Play: Small-Town Baseball in the Dirty 30s (Halifax: Nimbus, 1991), 119.

8 Quoted in Burton Russell, Nova Scotia Baseball Heroics (Kentville: self-published, 1993), 30.

9 Halifax Herald, May 19, 1936: 10.

10 Halifax Herald, May 19, 1936: 10.

11 John Lutz, “Pioneer on the Diamond, Ace on the Ice: Manny McIntyre,” in Arif Khadid and Keith Elman, In the Shadow of Obscurity: Toiling in a Reluctant Society (Los Angeles: ENH Publishing, 2020), 196.

12 Colin Howell, “Black Bases/Black Ice: The Multi-Sport Careers of Canadian Black Athletes and the Struggle for Social Justice,” paper presented at the Telling the Stories of Race and Sports in Canada Symposium at the University of Windsor in 2018. Paper here: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1015&context=racesportsymposium.

13 Telephone interview with Art Dorrington, March 20, 2012.

14 Interview with Darrell Maxwell, Truro, August 8, 2017; telephone interview with Grover “Deacon” Jones, March 24,2021.

15 Merritt Clifton, Disorganized Baseball: The Provincial League from LaRoque to les Expos (Brigham, Quebec: self-published, 1982), 7-18, 20; interview with John Mentis, Truro, August 8, 2017.

16 Frank Mitchell, The Boys of ’62. Transcending the Racial Divide (Halifax: New World Publishing, 2008), 139-141. Other team members included Denny Clyke, Dave Downey, Cecil Jackson, Sonny Parker, Ernie Symons, and Jim Tasco.