Union Park (Baltimore)

This article was written by Teddie Arnold

Although the home grounds of the Baltimore Orioles of the nineteenth century occupied several locations, the team found a permanent setting at Union Park between 1891 and 1899.

Baseball in Baltimore began around 1855. In 1882, as a charter member of the American Association, they were known as the Lord Baltimores. They won only 19 games and finished last while playing at Newington Park, located on Pennsylvania Avenue Extended on the northwest side of West Baltimore.1 At the end of the season, the team’s owner, brewery magnate Harry von der Horst, renamed them the Orioles2, and moved to a new location, known by contemporary historians as Oriole Park I (also known at the time as Huntington Avenue Grounds and/or American Association Park).3 During their six seasons there, they finished last three times and as high as third only once.

The team moved a third time for the start of the 1889 season to what is known as Oriole Park II, four blocks north of Orioles Park I, located at Greenmount Avenue (then York Road) between what is now 28th and 29th Streets.4 The struggling Orioles briefly dropped down to the minor league Atlantic Association for the 1890 season. However, halfway through the season, their AA replacement franchise, the Brooklyn Gladiators, folded, and the Orioles re-joined the American Association on August 3, 1890. 5

It was reported that the Oriole Park II was one of the most difficult ballparks for fans to reach of any grounds in the country.6 Dissatisfied with the location, Harry von der Horst announced shortly after opening day in 1891 that the team was moving four blocks south so that its games “will be within easier reach of the people.”7 The new grounds, which would be known as Union Park — also Orioles Park III –were located at the corner of Huntington Avenue (now East 25th Street) and Barclay Street, one block west of Oriole Park I.

The York Road branch of the Union horse car line ran within a few steps of the gate; the grounds now could be reached from nearly every section of the city by direct travel or transfers.

A double-decker grandstand extended from behind home plate down the first base line. A single deck down the third base line seated an additional 3,000 with 14 rows of orchestra chairs.8 The field sloped down from east to west, containing a mound, several trees, and a stream bed known as Brady’s Run, which created a perpetual swamp in right field oozing underneath the outfield fence.9 A space at the northwest end of the grounds of about 250 square feet was to be set up with tennis courts and tracks for amateur sports including baseball, lacrosse and football. One feature that still remained from Oriole Park I was the old clubhouse. It was said that the cost of “fitting up” the grounds was $7,500.10 At the time it was built, Union Park was the largest ballpark in the American Association and the first in Baltimore to have a double-decked grandstand.11 To the east of Union Park was Pompeiin Park, which contained a one-third mile running track, a bike path, and a 400 x125 foot lake for rowing and other aquatic sports. The grounds were available to amateurs at all times the Orioles were not playing.12

As the owner of the Eagle Brewery and Malt Works, Von Der Horst had been selling beer at Orioles games ever since he purchased the team back in 1882. Union Park contained a beer garden and a restaurant, prompting Von Der Horst’s notable quip: “Well, we don’t win many baseball games, but we sell lots of beer.”13

How Union Park got its name is up for debate. Historian James Bready notes that for 30 years, fans had ridden to games in cars pulled by horses. In the 1890s, the overhead-wire electrical method was introduced and by June 1, 1891, three passenger railway companies had consolidated into the Baltimore Union Passenger Railway Company. Bready suggests that as a business promotion, Union Passenger may have paid some of the new ballpark’s construction costs.14

However, there may be another explanation for the name. A company known as the Union Park Association had several years earlier secured a lease on the property. The Orioles took over the lease, so perhaps the name stuck out of familiarity.15

A crowd of over 10,000 paid 25 cents admission to see the Orioles’ first game at Union Park on May 11, 1891, at 4:00 p.m. against the St. Louis Browns, an 8-4 win for the home team.16 Former Oriole great Bobby Matthews was the umpire. The four-game series drew a reported 24,100. 17

It was reported that the Orioles were not able to hit well at Union Park because their eyes were blinded by the sun reflecting off the bare field. But the grass was beginning to grow and was expected to have made considerable progress when the team returned from their road trip.18 In late May, construction began on a new wooden clubhouse located in right field at the end of the grandstand.

By season’s end, the Orioles had managed a winning record while finishing third. In December, the American Association dissolved and the Orioles were one of four teams that joined the National League to form a 12-team circuit.

The start of the 1892 season did not go as planned. George Van Haltren briefly replaced long-time manager Billie Barnie. After the Orioles lost 10 of their first 11 games, Van Haltren was replaced by John Waltz, who didn’t fare much better. On May 10 he was replaced by Ned Hanlon. The Orioles finished dead last with a record of 46-101. The only highlight of the season came at home on June 10 when, during a 25-4 drubbing of St. Louis, Wilbert Robinson went 7 for 7 (a double and six singles), a major league record (since tied by Rennie Stennett of the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1975).19 The Orioles improved in 1893, but it wasn’t until 1894 that they would hit their stride. And that in no small part began with the hiring of a new head groundskeeper, Thomas Murphy. With 10 years of experience under his belt, Murphy no doubt knew what improvements were needed at Union Park. He assured Ned Hanlon he would have Union Park as “level as a billiard table” by the time the Orioles returned from spring training.20

Although the improvements to the field noted by the press made for good copy, Murphy’s changes to the diamond resulted in a great offensive weapon for Ned Hanlon’s brand of “inside baseball.”21 The advantages afforded by Murphy’s work were detailed in Peter Morris’s Level Playing Fields. The infield soil was mixed with clay and water, and when rolled became as hard as concrete. Placed in front of home plate, it led to the invention of the “Baltimore Chop.” The players would “hit down on the ball so sharply that they could make it to first base before any infielder could make a play.”22

The first base line was given a slight downgrade from home plate in order to assist players’ running efforts. From first to second base was given the same treatment. By contrast, Murphy built up the base paths from second to third base with an uphill grade. From third to home plate had a downhill grade, again to assist runners, and was built up from the outside to prevent bunted balls from rolling foul.23

The outfield was intentionally kept uneven, most notably the “hill” in right field where Willie Keeler roamed, and was considered a “terror of visiting players.” The grass in right field was always kept “ragged and full of weeds, rough spots, hollows, and hills” which enabled Keeler to successfully perform his hidden ball trick. Apparently, thanks to Keeler’s familiarity with the rough terrain in right field, he kept a stash of extra balls hidden in the weeds. When a visiting team hit a ball into the tall weeds, Keeler always managed to conveniently locate it. Balls hit by Oriole batters were not so easily located by opposing fielders, resulting in extra bases.24

A similar ploy was used on the pitching mound. In the era before rosin bags, pitchers would customarily pick up dirt around the mound with which to rub the ball down. Murphy would “sprinkle soap flakes near the rubber” that would end up in the hands of visiting pitchers. Oriole pitchers, however, knew strategic locations of dirt that were not covered in soap.25

Sportswriter Hugh Fullerton claimed that the totality of Murphy’s work at Union Park created “the most unfair grounds ever constructed,” maintaining that “the grounds, adapted perfectly to the home team’s style of play, did more to win pennants than anything else.”26

On Opening Day 1894 the Orioles beat the New York Giants, 8-3. The losing pitcher, Amos Rusie, ironically had been discovered by groundskeeper Thomas Murphy while working as a groundskeeper in Indianapolis in 1889.27

The Orioles’ explosive offense carried them to the 1894 National League pennant. A big factor was the team’s penchant for triples, a record 153. In the first game of a Labor Day doubleheader against the Cleveland Spiders, a crowd of 20,000 witnessed the Orioles hammer out 9 triples — a record that still stands.28 Left fielder Joe Kelley went 9 for 9, scoring 7 runs, setting a record still unmatched. In the afternoon game Kelley hit four straight doubles off Cy Young.29

Baseball was not Ned Hanlon’s only interest. In a scheme to fill the winter void, the owners of six clubs in the National League formed the first professional soccer league in the country in August 1894. Known as the American League of Professional Football (ALPF), the league featured teams in Baltimore, Boston, Brooklyn, New York, and Washington, D.C. Hanlon managed the Baltimore club (and would later be investigated by the U.S. Treasury Department for signing English professionals and claiming that they were American, in violation of immigration laws). The first professional soccer game in Baltimore took place at Union Park with Baltimore defeating Washington, 5-1.30

On the baseball front, Orioles management erected a “small cottage” inside Union Park to the left of the ticket office to be occupied by groundskeeper Murphy.31 Having Murphy live at the ballpark turned out to be a good decision. During the night of January 14, 1895, a fire destroyed the grandstand and clubhouses at Union Park. The first person to discover the flames was Thomas Murphy.

Once Von Der Horst worked through the insurance issues, plans for a new grandstand were immediately in the works. Work began in early March on what was described as “the best Baltimore has even seen.” The new park would again feature a double decker grandstand with private boxes, as well as press boxes and a telegraph box on the second level. The grandstand would not only be bigger, but it would be supported by iron pillars rather than wood.32

Playing in their rebuilt home grounds, the Orioles repeated their championship in 1895 and 1896, winning 90 games in ’96 and the Temple Cup playoffs.

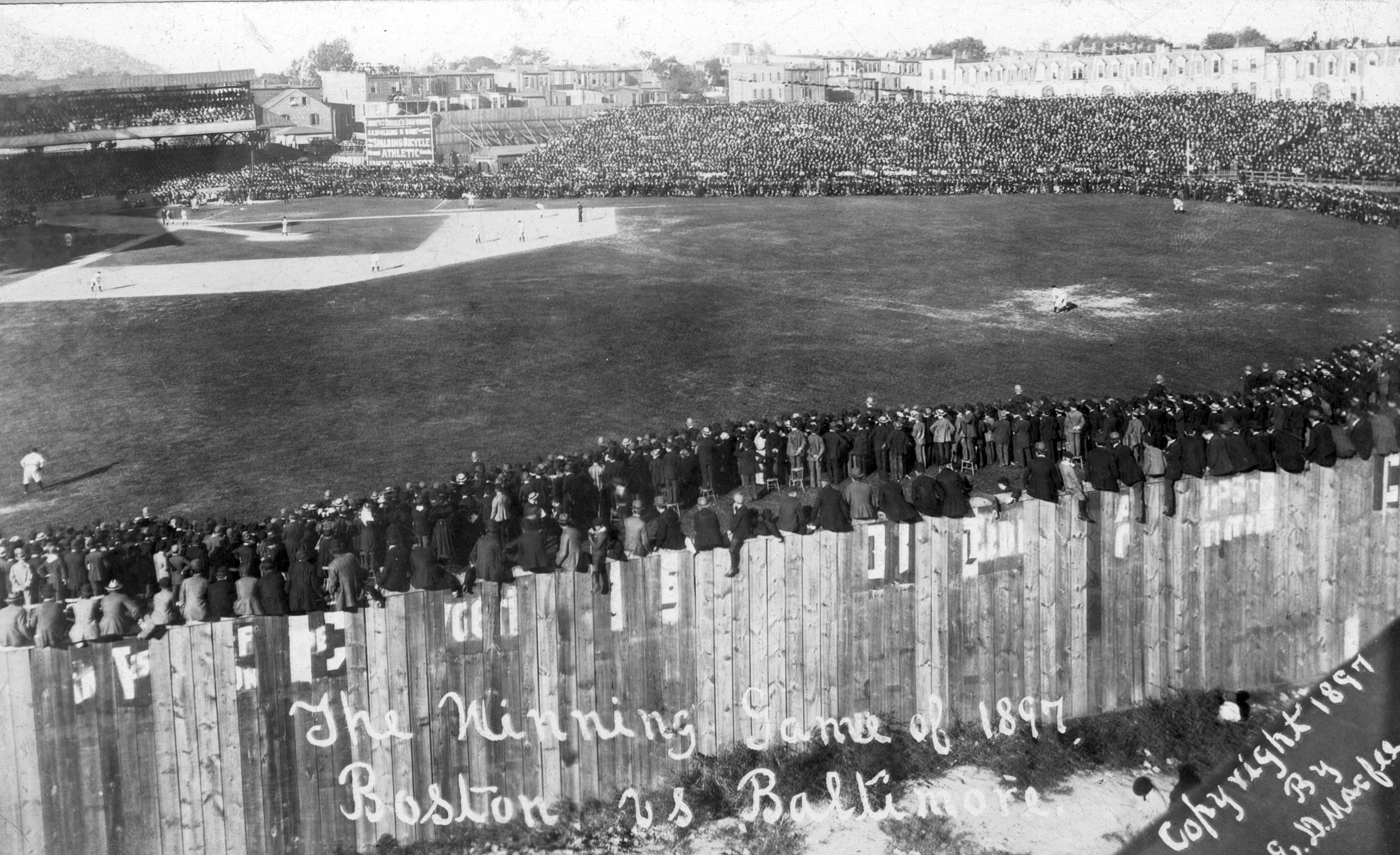

Opening day on April 22, 1897, began with a parade and ended with a win before one of the largest crowds ever seen at Union Park.33 The 1897 pennant race came down to a thrilling finish between the Orioles and the Boston Beaneaters. Huge crowds, including Boston’s famous Royal Rooters, filled Union Park to witness a crucial September series.34 Paid admission on September 27, 1897, was 18,123, reported to be a record for Union Park.35 The Orioles lost the three-game series and ultimately the 1897 pennant to the Beaneaters.

The few bright spots of the 1898 season included two 12-game winning streaks. The team also led the league in batting, stolen bases, and runs scored. Despite winning 96 games, the Orioles were outmatched by Boston, who took the pennant by 6 games. Attendance on the year was 123,416, less than half of what it had been during the pennant winning years, causing profits to take a hit and rumblings of syndicate baseball.36 To make matters worse, Thomas Murphy had left for Cincinnati to be the Reds’ groundskeeper.37

In order to cut his losses, Harry Von Der Horst acquired a controlling interest in the Brooklyn Trolley Dodgers, and moved his Orioles stars, including Willie Keeler, Joe Kelley, and Hughey Jennings, and manager Ned Hanlon to Brooklyn. John McGraw and Wilbert Robinson, who owned a successful business in Baltimore called the Diamond Café, refused to go. McGraw became the Orioles’ player-manager.

By all accounts, the Orioles exceeded expectations in the 1899 season. By mid-May, Hanlon dubbed them “the surprise of the season.”38 On July 4, history was made once again at Union Park when John McGraw became the first player to steal second, third, and home in the same inning.39

On October 10, 1899, the Orioles played their final home game of the season against Washington, and the final professional baseball game ever to be played at Union Park. The game ended in a 5-5 tie. In perhaps an ominous sign of the Orioles’ future, Frank De Haas Robison, syndicate owner of both the St. Louis and Cleveland clubs, was in attendance. Robison was quoted as saying the National League intended to honor its 10-year 12-team commitment, with the Orioles playing another two years in Baltimore.40 It didn’t happen.

By season’s end, the McGraw-led “leftovers” (as dubbed by Burt Solomon) finished with an 86-62 record, good for fourth place, 15 games back of pennant-winning Brooklyn. Following the season, the National League contracted to eight teams, without the Orioles.

Although the official announcement of the league contraction would not occur until March, a movement had immediately begun following the end of the season to revive the defunct American Association. Looking to capitalize on the National League castoffs and growing resentment among players (mostly over salary and the reserve rule), the effort attracted Cap Anson and John McGraw to lead the charge. Having learned that Hanlon and Von Der Horst had inadvertently allowed their lease on Union Park to lapse on January 3, McGraw swooped in and secured the rights to the grounds on January 25.

It was noted that trustees of the Sadtler estate, the park’s owners, “were extremely favorable to the new team and were willing to give it preference.” The lease terms were for one year at a rent of $3500, and would be in the name of Philip Peterson, a stockholder in the new company. However, the lease was subsequently transferred to the Baltimore Amusement Company, the official owner of the purported new franchise.41 So popular was McGraw’s coup that prominent members of Baltimore society were continually approaching him to purchase stock in the new company, which was capitalized at $20,000 –200 shares at $100.

The lease included the land, the stands, clubhouse, and other improvements that had been made and paid for by Von Der Horst’s Exhibition Company.42 On Saturday, February 3, the Baltimore Amusement Company was granted an injunction against the Exhibition Company from “removing or destroying any of the fixtures at Union Park.” On that same day, Hanlon and company put armed guards at the gate of Union Park and nailed “No Trespassing” signs to the fencing.43 When McGraw’s forces attempted to gain access to the grounds and were stopped by Hanlon’s men, some of them scaled the fence and jumped down onto the roof of Murphy’s cottage. A fight broke out. While police broke it up, McGraw’s men, carrying guns and clubs, set up camp at third base. On the other side of the diamond, Hanlon’s men set up shop at first base. A single police officer took his post in front of the ticket office. This scene would remain for much of the month while the battle continued in the courts.44

It wasn’t long until the ground beneath the upstart American Association started to crumble. Within a few weeks of the skirmish, McGraw announced that the new league could not mobilize in time to play in the upcoming season.45 Maybe out of pride or spite, McGraw voiced his intentions to continue the legal battle over the rights to Union Park despite the lost season. However, once reality set in, rumors started to spread that McGraw’s financial backers were looking for ways to settle the dispute with Hanlon.46 After much back and forth, a compromise was finally struck between the two companies. The Exhibition Company agreed to pay $3500 to the Amusement Company — the balance of one year’s rent, in addition to an estimated sum of $1500 to $2000, which purportedly represented the expense incurred by the Amusement Company to establish a team in Baltimore.47 Notably, this compromise would also end any bad blood between Hanlon and McGraw, as Hanlon was “inclined to forgive and forget, and make McGraw manager of the Baltimore team next season.”48 With the matter now settled, the Amusement Company planned to hold a banquet at the Eutaw House, with Hanlon and Von Der Horst as distinguished guests.49

In early March, the National League announced Baltimore’s exit from the circuit. With the lack of a professional team, Union Park would be home to games of the Atlantic Association.50 McGraw and Robinson signed with the St. Louis Cardinals for 1900. Before departing they made a final curtain call at Union Park in a game between the Baltimore newspapermen and the cast of “Broadway of Tokio.” In what was dubbed a “horrible game of baseball,” the Robinson-led actors prevailed in a “painful score” of 19-0 over McGraw’s newspapermen.51

Although Baltimore had gone the entire 1900 season without professional baseball (the only such year from 1882 to present day), that was about to change, as McGraw and Robinson landed the Baltimore franchise in Ban Johnson’s new American League. McGraw voiced his opinion that new grounds would have to be built to house the new franchise, as the lease for Union Park was set to expire in two years.52 McGraw was unwilling to consider Union Park unless the lease terms were renegotiated.

By early January, McGraw and company had signed a five-year lease for the land upon which American League Park was to be built, located about three blocks north of Union Park. What was to become of old Union Park? Hanlon – still the leaseholder – signed over rights to former Oriole catcher William J. “Boileryard” Clarke, now with the Boston Beaneaters, who held rights to an American Association franchise in Baltimore. Hanlon and others in the National League hoped to revive the American Association to compete with the American League. Recognizing that Union Park was prime real estate, Hanlon hoped that the grounds would be of use in attracting a franchise to Baltimore. However, the effort to revive the American Association and attract a new franchise to Baltimore failed.

Despite the fact that Union Park was still in use by college and local teams, it was reported in early 1902 that the grounds would be cut up into building lots following the expiration of its lease in March 1903. Although still under lease by the National League (through the Baltimore Baseball and Exhibition Company), who were on the hook for a final year’s rent of $3500, speculation was that the NL would allow the lease to lapse. With the erection of American League Park, the National League, who had secured the site to prevent the American League from getting it, had no further use for the old ballpark.53

After the AL and NL signed a peace agreement in 1903, Johnson found a buyer in New York for the Baltimore franchise.

The newly constructed American League Park was placed into receivership, with the stands and buildings to be auctioned off. Meanwhile, Hanlon was vocal about his opinion that the National League would benefit from a team in Baltimore and that Union Park was still a suitable grounds, even better located than American League Park.54 The old skipper couldn’t seem to let go of his old stomping grounds.

Although Hanlon’s hopes were still high for a Baltimore franchise, any hopes of playing at Union Park were dashed when the National League officially decided to allow the lease to expire in February 1903. In addition, the end of Union Park was signaled as the league appointed Hanlon to “sell the old stands, lumber and all movable property belonging to the old club. . . [t]hus will pass away the ball park that Hanlon’s old champions made famous in the last decade.”55 By year’s end, the lumber that made up the stands at Union Park had been sold, and the park was awaiting demolition.56 Hanlon did finally manage to bring baseball back to Baltimore, albeit in the form of an Eastern League franchise. Their new home would be American League Park, which Hanlon had purchased out of receivership for $3,000.57

It is unclear when Union Park was officially torn down. Throughout 1903 and 1904, there are references to teams playing at a “Union Park,” but it seems unlikely that this was the same stadium.58 What is clear is that the vacant Union Park lot was purchased by Howard G. White on October 2, 1905. It was expected that the land would be improved with dwellings; the site consisted of 1800 building feet and could accommodate 120 houses.59 In a eulogy run by the Baltimore Sun, Union Park was remembered for its history with the old Orioles and the name Union Park “would always be associated in the memory of local rooters with Baltimore’s palmiest baseball days.”60

Palmiest days indeed. The Orioles’ success playing at Union Park had been remarkable. In 599 games at Union Park, the Orioles had managed to amass a record of 413 wins and 186 losses, for an astounding winning rate of .680 (by contrast, baseball teams today have a home winning percentage that averages around .550). With Union Park gone, baseball would continue on in Baltimore, but the memories of the old ballpark remained. Perhaps out of habit or nostalgia, years later it was reported that players of the new Eastern League Baltimore team would refer to their new home as “Union Park” on occasion.61 The old park was gone but not forgotten.

Acknowledgments

This article was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Notes

1 James H. Bready, Baseball in Baltimore: The First Hundred Years (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 17.

2 Team owner Harry Von Der Horst allegedly named the Orioles after the Order of the Orioles, a local social club whose major activity was an annual Mardi Gras style parade. See Jack Kavanaugh and Norman, Uncle Robbie (Society for American Baseball Research, 2000), 11.

3 Orioles Park was located at what is now East 25th Street (then Huntington Avenue) and Greenmount Avenue (then York Road). See Bready, Baseball in Baltimore, 38.

4 Ibid, 47.

5 The Orioles ended up winning the Atlantic Association pennant on the final day of the season, August 25, 1890. See Uncle Robbie, 11

6 “New Base-Ball Park,” Baltimore Sun, April 25, 1891: 3.

7 Ibid, 3.

8 The total seating capacity of Union Park when it opened is unclear, as seats were progressively added over the years.

9 “New Base-Ball Park,” Baltimore Sun, April 25, 1891: 3; Peter Morris, Level Playing Fields: How the Groundskeeping Murphy Brothers Shaped Baseball (University of Nebraska Press, 2013), 64.

10 “New Base-Ball Park,” Baltimore Sun, April 25, 1891: 3

11 Bready, Baseball in Baltimore, 59.

12 “The Whole Plan And Scope,” Baltimore Sun, April 27, 1891: 1.

13 Burt Solomon, Where They Ain’t: The Fabled Life and Untimely Death of the Original Baltimore Orioles, the Team That Gave Birth to Modern Baseball (Doubleday, 1999), 40.

14 Bready, Baseball in Baltimore, 50.

15 “The Whole Plan And Scope,” Baltimore Sun, April 27, 1891: 1.

16 Bready, Baseball in Baltimore, 51; “Classified Ad 2,” Baltimore Sun, May 11, 1891: 1; “Opened with a victory,” Baltimore American, May 12, 1891: 5.

17 “Four Thousand Saw It,” Baltimore Sun, May 14, 1891: 3.

18 “Talk Of The Players,” Baltimore Sun, May 21, 1891: 4.

19 Bready, Baseball in Baltimore, 59.

20 “Sporting Gossip,” Baltimore Sun, March 19, 1894: 10.

21 Morris, Level Playing Fields, 34.

22 Morris, Level Playing Fields, 35.

23 Morris, Level Playing Fields, 35; Solomon, Where They Ain’t, 71.

24 Morris, Level Playing Fields, 36; Solomon, Where They Ain’t, 71, 76.

25 Morris, Level Playing Fields, 36; Solomon, Where They Ain’t, 71 (Solomon notes that Orioles’ pitchers carried dirt on their pockets)

26 Morris, Level Playing Fields, 36

27 Solomon, Where They Ain’t, 71; This fact has been disputed by Peter Morris, who claims that it was more likely Tom Murphy’s brother John, also a groundskeeper, who discovered Rusie. Morris, Level Playing Fields, 33.

28 “Triples Team Records”, baseball-almanac.com.

29 Bready, Baseball in Baltimore, 79-80.

30 http://amofb.blogspot.com/2014/01/the-first-professional-soccer-league-in_17.html

31 “Ground-Keeper Murphy’s Lodge,” Baltimore Sun, October 29, 1894: 7.

32 “World of Sport,” Baltimore Sun, February 27, 1895: 6.

33 “61,000 See The Games,” Baltimore Sun, April 23, 1897: 6.

34 “The Crowds Far And Near,” Baltimore Sun, September 25, 1897: 6.

35 “Hurrah For Boston,” Baltimore Sun, September 27, 1897: 6.

36 Bready, Baseball in Baltimore, 98-99.

37 “Groundkeeper Murphy Leaves,” Baltimore Sun, October 22, 1898: 8.

38 “Mr. Hanlon In Town,” Baltimore Sun, May 15, 1899: 6.

39http://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/july-4-1899-baltimores-john-mcgraw-first-player-steal-second-third-and-home-same

40 “De Haas Robison Here Again,” Baltimore Sun, October 11, 1899: 6.

41 “Union Park Captured,” Baltimore Sun, January 26, 1900: 6.

42 Ibid.

43 Solomon, Where They Ain’t, 184.

44 Solomon, Where They Ain’t, 184. Author and historian Charles Alexander provided a slightly different account, where he noted that Peterson managed to climb the fence, pummel one of the guards, leaving in his pocket a court order. Alexander also noted that Hanlon’s men had no plans on leaving so they erected a tent in the left field bleachers, in addition to occupying the clubhouse and Tom Murphy’s old cottage. Charles Alexander, John McGraw (University of Nebraska Press, 1995), 69.

45 Alexander, John McGraw, 69.

46 “New Baseball Phase,” Baltimore Sun, February 21, 1900: 6.

47 “Baseball Tempest Over,” Baltimore Sun, February 26, 1900: 6.

48 Ibid.

49 “Association Boomers,” Baltimore Sun, March 1, 1900: 6.

50 “Atlantic Baseball Association,” Baltimore Sun, April 30, 1900: 6; “Baltimore Baseball League,” Baltimore Sun, May 18, 1900: 6.

51 “Joyful Baseball,” Baltimore Sun, May 4, 1900: 6.

52 “Baseball Coming To A Point,” Baltimore Sun, November 12, 1900: 6.

53 “Old Union Park Is Doomed,” Baltimore Sun, January 31, 1902: 6.

54 “Will Old League Buy,” Baltimore Sun, October 21, 1902: 6.

55 “Hanlon Has Hopes,” Baltimore Sun, December 15, 1902: 6.

56 “Baseball,” Baltimore Sun, December 27, 1902: 6.

57 “Hanlon’s Ball Park Now,” Baltimore Sun, January 1, 1903: 9.

58 “Marston’s Defeats Country School,” Baltimore Sun, November 14, 1903: 9; “Amateur Ball Clubs, Baltimore Sun, July 21, 1904: 9; “Baseball Cops Are Working,” Baltimore Sun, August 18, 1904: 9; “Sparrows Point Ends Play,” Baltimore Sun, October 30, 1904: 10; “Barclay, 6; Sparrows Point, 0,” Baltimore Sun, November 27, 1904: 10.

59 The Sadtler estate, which owned the lot on which Union Park stood, sold off their last unimproved lot by November 19, 1905, disposing entirely of everything in the estate.

60 “Old Union Park To Go,” Baltimore Sun, October 2, 1905: 12.

61 “Orioles Warming Up,” Baltimore Sun, March 17, 1908: 10.