J.L. Wilkinson and the Rebirth of Satchel Paige

This article appears in SABR’s “When the Monarchs Reigned: Kansas City’s 1942 Negro League Champions” (2021), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

By the fall of 1938 Kansas City Monarchs owner J.L. Wilkinson was well aware of the marketing potential of Leroy “Satchel” Paige. The Monarchs had seen the talented pitcher on opposing teams over the years, and Wilkie (as Wilkinson was known to his players) had often taken advantage of Paige’s practice of assuring that he could be rented out to clubs other than the one he was playing for. Now Wilkinson was about to take full advantage of Satchel’s star power.

By the fall of 1938 Kansas City Monarchs owner J.L. Wilkinson was well aware of the marketing potential of Leroy “Satchel” Paige. The Monarchs had seen the talented pitcher on opposing teams over the years, and Wilkie (as Wilkinson was known to his players) had often taken advantage of Paige’s practice of assuring that he could be rented out to clubs other than the one he was playing for. Now Wilkinson was about to take full advantage of Satchel’s star power.

In 1934 Paige pitched for the Monarchs in a game against an all-star team put together around the St. Louis Cardinals Gas House Gang’s ace pitching duo, Dizzy and Paul Dean. The Monarchs hired Paige again the next year for another series against the Dean All-Stars. Dizzy told Paige as they were saying goodbye after the tour, “You’re a better pitcher’n I ever hope to be, Satch.”1 On another occasion, Dizzy said, “If Satch and I was pitching on the same team, we’d cinch the pennant by July Fourth and go fishin’ until World Series time.”2

During portions of two seasons (1933 and 1935) Paige pitched for car dealer Neil Churchill’s integrated team in Bismarck, North Dakota. The ethnically diverse team also had a Cuban, a Jew, a Lithuanian, an Italian, an Irishman, a Swede, and a German, much like J.L. Wilkinson’s famed All Nations club. Paige pitched in more than 60 games in three months for the Churchills, won 30 of 32 decisions, and averaged nearly 15 strikeouts per game. More than once Wilkinson’s Monarchs played the Churchills while they were barnstorming. For example, in June 1935, Paige hurled a 2-0 shutout against the Monarchs’ Chet Brewer.

While playing for Bismarck in the summer of 1935, Paige said he was given some snake oil by Sioux Indians he met. They told him it was “hot stuff” and not to put it on anything but snake bites. Figuring it might be good for him in the cold North Dakota air, Paige put some on his arm after pitching and it loosened him up. He began using it after every game and kept some on hand in a jar.3

With the help of stars like Quincy Trouppe, Hilton Smith, and Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, the Bismarck team won the 1935 National Baseball Congress Tournament in Wichita, Kansas. After the tournament, the Churchills barnstormed their way to Kansas City, where, on September 15, Paige (with Radcliffe as his batterymate) took the mound against the Monarchs. Satchel told Churchill the umpire’s tight strike zone was causing him “unwarranted pain and suffering” and he wanted to leave the game. Churchill appealed, saying it was his last game as manager, and offered Satchel an extra $750 if they beat the Monarchs. Satchel relented, struck out 15, and pocketed the cash after an 8-4 victory.4

In the spring of 1936, Paige rejoined Gus Greenlee’s Pittsburgh Crawfords, where he had played earlier in the 1930s. In 1937 Satchel left the Crawfords to play for a month in the Dominican Republic, for the Dragons, a team sponsored by dictator Rafael Trujillo. He was 8-2 and won the championship game.

When Paige and the other players who had jumped to the Dominican Republic returned to the States, they formed an all-star team that outdrew Negro League clubs. Greenlee offered him $450 a week to return to the Crawfords, but Satchel told him, “I wouldn’t throw ice cubes for that kind of money.”5 Greenlee then sold Paige’s contract to the Newark Eagles for $5,000, but the “travelin’ man,” as Satchel called himself, went to Mexico instead, where he signed for $2,000 a month. Enraged, Greenlee led the charge that resulted in Negro League owners voting to ban Paige for life.6

In Mexico, Paige’s arm hurt so much he could barely throw. He was hit hard by virtually every batter he faced. At times Satchel said that the spicy Mexican food was to blame for his arm trouble.7 On other occasions he said he had run out of the special oil the Sioux Indians had given him. In fact, years of pitching so many games had caught up with Satchel. Some speculate he had suffered a rotator cuff injury. Infielder Newt Allen said Satchel’s arm had gotten so bad he couldn’t rub the back of his neck.

Looking back, a decade later, the Kansas City Call suggested alliteratively, “[t]he great one owned a wing that was as dead as a new bride’s biscuit. … It was at that time that J.L. Wilkerson [sic], owner of the Monarchs, toyed with the idea of employing Satch, who was nursing the once-poisonous paw in pathetic pity.”8 Indeed, almost everyone in the baseball world, except Wilkinson, thought Paige was washed up. He called Paige, and Satchel remembered the conversation well:

“Satch, this is J.L. Wilkinson. I own the Kansas City Monarchs. Remember me?”

Paige said, “I remembered good. I’d put in some time for Mr. Wilkinson. … ‘Yes, sir, Mr. Wilkinson,’ I said.”

“Satchel, Tom Baird, my partner, and I just got your contract from Newark. When can you report to Kansas City?”

“I can be there tomorrow.”

“Make it next week and meet me there.”

Satchel said he felt “I’d been dead. Now I was alive again. I didn’t have an arm, but I didn’t even think of that. I had me a piece of work.”9

Wilkinson’s signing of Paige turned out to be transformative for the Monarchs as well. As John Holway has described the moment: “[T]he decision Wilkinson made, while they talked, represented the second great achievement that would help bring the Monarchs a new dynasty [the first being night baseball]. It was an achievement born of baseball acumen, of wisdom about muscle and bone, skill and sporting spirit. Wilkinson decided to give Satchel Paige a second chance.” As it turned out, “Wilkinson saved Satchel Paige’s career. And Paige rejuvenated the Monarchs.”10

When Paige met Wilkinson and Baird, he explained that he couldn’t throw. Wilkinson responded that the plan was for him to play first base. Then Satchel asked when he could join the Monarchs. Wilkinson was quiet for a moment, then said, “[Y]ou’re not going to play with the Monarchs. We’ve got a Monarchs traveling team, a barnstorming team. We planned to send you up North on a tour with them. You couldn’t pitch with that arm of yours, and you haven’t played first enough to hold it down in the Negro Leagues.”

Paige said, “that good feeling I’d had just sort of floated away.” However, he said to Wilkinson, “I guess that’s how it will be.”

Then Paige asked why Wilkinson was giving him a job, if he wasn’t good enough for the Monarchs.

“We think you’re still big enough to pull the fans,” Wilkie said.

“My name,” Paige responded, “ain’t gonna lure that many fans.”

Wilkinson was quiet again for a moment, then said, “It’ll lure enough. Anyway, I thought you needed a hand.”

In a 1971 interview, Bill “Plunk” Drake said “Wilkerson,” whom Drake called an “awful good man,” even took Satchel to Chicago for treatment of his stomach trouble.11

Wilkinson and Paige may have been pleased that Satchel would be playing again, but Effa Manley, co-owner with her husband, Abe, of the Newark Eagles, and the only woman inducted (with Wilkinson in 2006) into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, was furious. She believed that the Monarchs owner should have sided with her when Satchel jumped his contract with the Eagles to play in Mexico. She accused Wilkinson of being no different than other White booking agents or ballpark owners, interested only in making money, and threatened to sign players from the Monarchs in retaliation.12 Wilkinson responded to Mrs. Manley’s outrage calmly, telling her that “no one had offered Paige a contract, so I picked him up.”14 Technically, Wilkinson was right. The deal in which the Crawfords had sold Paige’s contract to the Eagles was contingent on Satchel showing up, and he hadn’t.

In the end, Paige was allowed to remain with the Monarchs, and the Eagles were permitted to keep two Negro American League players they had signed in violation of interleague rules.

According to Monarchs pitcher Chet Brewer, the first thing the Monarchs owner did after signing Paige in 1938 was to take Satchel to a dentist and get him a new set of teeth. Wilkinson just had a way, Brewer said, of knowing what a player needed.13 As J.L.’s son, Dick, said, “Satchel had a ‘whalebone arm,’ all bone, not much muscle. Dad could tell by looking at a ball player whether he could play ball or had potential. They talked, and Dad gave him another chance.”14 Buck O’Neil remembered that “J.L. Wilkinson saw the potential there [in Paige, after he hurt his arm], knew that he was a great drawing card.”15

According to Monarchs pitcher Chet Brewer, the first thing the Monarchs owner did after signing Paige in 1938 was to take Satchel to a dentist and get him a new set of teeth. Wilkinson just had a way, Brewer said, of knowing what a player needed.13 As J.L.’s son, Dick, said, “Satchel had a ‘whalebone arm,’ all bone, not much muscle. Dad could tell by looking at a ball player whether he could play ball or had potential. They talked, and Dad gave him another chance.”14 Buck O’Neil remembered that “J.L. Wilkinson saw the potential there [in Paige, after he hurt his arm], knew that he was a great drawing card.”15

Wilkinson sent Satchel, with Newt Joseph, to play in the West, all the way to Canada, on a team sometimes called the “Second Monarchs,” “Junior Monarchs,” or “Kansas City Travelers.” The players often called the team the “Baby Monarchs.” During one stretch, the Shreveport Acme Giants journeyed with the Travelers and played against them, O’Neil recalled.

With the Monarchs traveling squad, before a game, Satchel would often perform a “pepper show,” doing tricks with the ball, like rolling it across his arm and chest to the other arm and hand, and some shadowball playing, slow-motion throws, and gags. When the game started, he would sometimes take the pitcher’s mound and soft-toss his way through a few innings with what he called his “Alley Oops and Bloopers.” Then he would play first or occupy the first-base coaching box, to the delight of the fans in the small towns where they played.16

As Satchel remembered, on the traveling team the other players at first treated him like he “was dead and buried.” About the only one not like that was Newt Joseph, an old-timer who was the traveling club’s secretary, who told him “maybe we can work that arm of yours out.” At least, Paige said, he was making spending money.17

Before long, the Monarchs “B” squad was outdrawing and earning more than the main team, because of the “Paige effect.” Wilkinson wisely began advertising the Travelers as “Satchel Paige’s All-Stars.” They played games against “community teams, post office teams, industrial league teams, church squads, Sunday-school teams, railroad-sponsored teams, pharmacy-sponsored teams, and any local nine that came together with enough cash to sponsor the contest, cover travel expenses, and guarantee a reasonable gate.”18 For many semipro teams, the entire year’s budget was based on booking Paige. He kept many clubs solvent just by appearing.

The Monarchs traveling team included young talent but also older players such as Newt Joseph as well as George Giles and Cool Papa Bell. Paige respected Wilkinson for giving jobs to older players like him, whom others ridiculed as being past their prime. He quoted Wilkinson as saying, “[t]hey can still do some good. And they’ve done a lot for the Negro Leagues and made us all some money, so I’m just trying to pay them back a little.” Wilkinson also realized that their well-known names would still be draws at the box office. The Paige All-Stars toured the Northwest and played in the California Winter League as well as barnstorming in the Midwest. Backed by Wilkinson, Paige refused to play in towns where they could not eat or sleep. Wilkinson also made “Jew Baby” Floyd the pitcher’s personal trainer.19

One of the most successful matchups was between Paige’s All-Stars and the Ethiopian Clowns. On June 11, 1939, 4,000 turned out in Peoria, Illinois, to see the two teams split a doubleheader. According to the June 16 Call, the Clowns “captured the crowd’s fancy in both games with their whirlwind fielding practice speed and their determined efforts.” Their “remarkable shadow ball exhibition took the crowd by storm.” The two teams met again in Milwaukee.

During the 1939 barnstorming season, while the traveling squad was in Canada, Satchel’s arm and overpowering fastball miraculously returned. Some say it was on a warm Sunday, as he pitched against one of the House of David teams, that Satchel’s arm strength and fastballs returned. O’Neil recalled: “‘Jew Baby’ Floyd went out to rub Satchel’s arm, and … his arm came back, the batters didn’t hold back [as they had at first been instructed to do by Wilkinson], and he struck out seventeen in one night.”20 Floyd’s remedies were “massages, ointments (including one he called ‘Yellow Juice,’ so potent it scared away mosquitoes), a combination of scalding and ice-cold baths for his arm, and warm and cold wraps.”21

Newt Joseph “called Wilkinson, [and] said ‘[Satchel’s] ready to come back,’ so he came back to the Monarchs. He was a natural showman. He was just a natural.”22 Satchel’s control was once again excellent. “He could throw the ball right by your knees all day,” said Cool Papa. However, Wilkie “told Paige to take it easy and to stay with the traveling squad through the end of the season.” Wilkinson had not yet received league approval to reinstate Paige, but he was sure he would because of the hurler’s box-office appeal.23

Without Paige the Monarchs won the first-half 1939 NAL pennant race and met the winners of the second half, the St. Louis Stars, in a playoff for the league championship. Kansas City won the series, taking four of the five games played. During the playoffs, Satchel Paige’s All-Stars were guests of the Monarchs management. Receipts of one of the games played went to a rescue mission.

The Monarchs ended the 1939 season with two “dream games” against Satchel Paige’s All-Stars (who, the Call pointed out, were under Monarchs management) the last week in September at Ward Field in Kansas City, Kansas. The Monarchs won them both, 11-0 and 1-0. Paige pitched four innings in the first game and gave up seven runs. Hilton Smith hurled for the Kaysees, scattering four hits.24

The dispute over rights to Paige festered on, finally coming to a head when, on June 27, 1940, the Negro National League and the NAL came to an agreement that both leagues had a justified claim on Paige. However, Paige indicated he wanted to stay with the Monarchs. Almost 30 years before Curt Flood challenged the reserve clause in the White major leagues, Paige contended that slavery was over and he could play for whomever he pleased. “The leagues’ owners tried to strong-arm Paige to leave the Monarchs for the Eagles and told him that unless he did, ‘there will be a war between the two leagues.’”25 However, as historian Donald Spivey has noted, “Paige and Wilkinson ignored the threats. Paige was declared ineligible for the 1940 East-West All Star Game in Chicago, but he just continued barnstorming and going south to the Caribbean islands.”26

In late September 1940, after Paige had completed two years on the Monarchs traveling team, Wilkinson decided the time was right for the pitcher to rejoin the main Monarchs club. He signed Satchel to a new contract for the 1941 season and sweetened the deal with something he knew Paige would love – a new car. To test him out, Wilkie put Paige to work before the 1940 season ended. Satchel’s first start in Chicago, against the American Giants, drew 10,000; the next game in Detroit brought out 12,000 fans.

Having showcased Paige’s box-office appeal, Wilkie next sent Satchel to the Puerto Rican winter league, where he was named the league’s most valuable player.27 According to Paige biographer Larry Tye, J.L. Wilkinson “was savvy enough to know that Satchel’s two years of toiling in the wilderness with the traveling team had kept him out of sight and mind of Negro sportswriters and their hundreds of thousands of readers. So he enlisted New York playwrights Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman to help script the pitcher’s return.”28 They agreed that the only proper platform to reintroduce Paige was New York City, so Wilkinson booked him to pitch the 1941 season opener for the New York Black Yankees on May 15. Mayor Fiorello La Guardia threw out the first pitch before a record crowd for an opening-day Negro League game: 20,000. Paige pitched all nine innings, struck out eight, and won the game over Philadelphia, 5-3. The game was covered not only by the Black press but also by the New York Times. Life magazine ran an article on Paige in its June 2, 1941, issue. Effa Manley objected, but promoter Eddie Gottlieb pointed out to her that having Paige pitch was helping the Black Yankees get out of debt.

A week later Paige pitched the Monarchs home opener and let it be known that his habit of jumping teams was over. With his fastball reduced, as Paige put it, from “blinding’ speed” to “just blazin’ speed,” he relied more on a curve, a knuckleball Cool Papa Bell had taught him, and a slow sinker. Drawing on the still strong buzz surrounding Paige’s traveling team, in June 1941 Wilkinson reassembled the Paige All-Stars for a doubleheader against the Ethiopian Clowns at Crosley Field in Cincinnati.29

By midseason in 1941 Paige’s rehabilitation with Negro League owners was complete. Wilkinson and Baird were willing to lend Paige to any NNL team for exhibition games … at a price. Eddie Gottlieb promptly booked another doubleheader in Yankee Stadium for July 20, featuring Paige’s Monarchs and three NNL teams. Philadelphia and other NNL clubs also booked the Monarchs on the Kansas City team’s Eastern swing. A large crowd showed up at Parkside Field in Philadelphia on July 17, 1941, in response to advance publicity that promised Paige “will definitely hurl part of the game.”30

Paige received 276,418 fan votes for the 1941 East-West All-Star Game, 100,000 more than the next pitcher, the Monarchs’ Hilton Smith. Satchel was cleared to play by the owners and pitched two innings in the July 27 game in Chicago. It didn’t matter that Paige’s West team lost, 8-3. The fans had seen Satchel pitch.31

Wilkinson surely understood that the Kansas City Monarchs were well on their way to morphing into the Paige All-Stars. After Paige joined the team, in addition to their games in Kansas City and in the Midwest, they were playing to huge crowds throughout the East, with the stipulation that Wilkinson’s team get a higher percentage of the gate for the privilege of having Paige on the field.32

According to his Monarchs teammate Chet Brewer, who had also played with Paige on the Bismarck, North Dakota, team, Wilkinson would “hire [Paige]” out on Sunday and take 15 percent off the top of the gate receipts, right after the government got their money.”33 In particular, whenever a team was in financial trouble, Wilkinson’s willingness to “lend” Paige helped the team boost gate receipts. Of course, the deal would also put money in Paige’s and Wilkie’s pockets.

Because Paige was perpetually late to games, Wilkinson had Brewer sometimes ride with him. After one harrowing trip, Brewer told J.L., “I don’t want to ride with Satchel anymore. He’s going to get us both killed.” Satchel would pitch a game at Yankee Stadium on a Sunday, then take off in his big Cadillac and not show up until the next Sunday. “The Monarchs put up with it,” Brewer said, “because they were making money off him. J.L. got rich on him.”34

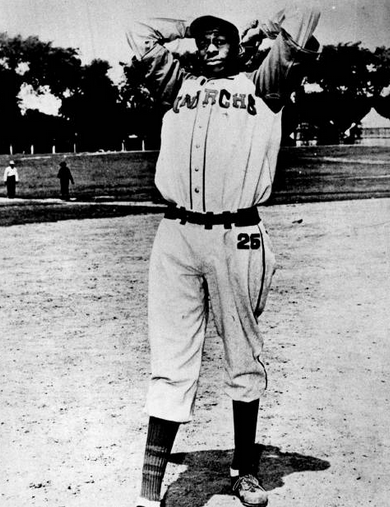

After Satchel Paige’s dead arm recovered while he pitched for J. L. Wilkinson’s traveling Monarchs B-team, his career literally took off again. (Courtesy of William A. Young)

At the same time as Wilkinson was treating Satchel with dignity and respect (and cashing in on his fan appeal), the White media, now well aware of the public’s interest in the lanky Monarch hurler, portrayed him stereotypically. In its June 30, 1940, edition, Time featured Paige in a condescending article, calling him “Satchelfoots.” A month later the Saturday Evening Post’s Ted Shane wrote an article on Paige. It was titled “The Chocolate Rube Waddell,” and described Black baseball as “much more showman like than white baseball. … Their baseball is to white baseball as the Harlem stomp is to the sedate ballroom waltz. … They play faster, seem to enjoy it more than white players.” According to Shane, Paige had “apelike arms” and a “Stepinfetchit accent in his speech,” but “behind his sleepy eyes was a shrewd brain.”35

Frazier “Slow” Robinson played with and became a good friend of Paige when both were on the Monarchs in 1942. Robinson believed that “J.L. Wilkinson knew what made Satchel tick.” He “knew that as long as Satchel lived out of a suitcase” he was liable to vanish at any time. So Wilkie took Paige under his wing, as he did his own children. He helped Satchel buy a home in Kansas City. It was the first time Satchel had any home to go back to. According to Robinson, “Wilkinson let him know the value of making money while you were able to make it. Especially playing baseball.” Wilkinson was showing him that “if he wanted to make something of himself, he’d have to change his way of living.” Satchel “never did jump anymore,” Robinson pointed out.36

There must have been some confusion as to Satchel’s status with the Monarchs at the outset of the 1942 season, as the Kansas City Call felt it necessary on April 24 to assure fans Paige would be back with the team for the season.

Before the 1942 regular season started, Paige was already drawing fans to exhibition games. An overflow crowd of 15,000 saw the Monarchs split a doubleheader with the Homestead Grays at Pelican Stadium in New Orleans on Sunday, April 26. Paige pitched five innings in the nightcap.37

Paige was on the mound in the second game of a doubleheader with the Memphis Red Sox on May 3 at Martin’s Park in Memphis. He pitched the first four innings, giving up three runs, before Hilton Smith took over. Smith held the Memphis bats in check for a 4-3 victory. Paige was scheduled to pitch on May 6 in another game with the Red Sox, but he refused and was fined $25.

Paige’s first appearance in the 1942 regular season was in a doubleheader with the Chicago American Giants on May 10 in Chicago. The May 15 Call reported that “Old Satchel” showed “some of the smartest pitching of his brilliant career,” going five innings in a 6-0 victory.

In the Monarchs’ 1942 home opener on May 17, Paige took the loss (4-1) in the second game of a twin bill against the Memphis Red Sox. According to the May 22 Call, Paige’s “jump ball” was hopping but his change proved to be his undoing.

On May 24 the Monarchs took on Dizzy Dean and his major-league all-star team at Wrigley Field in Chicago. Most of the nearly 30,000 in attendance were Black. According to the May 29 Call, Dean hadn’t been able to heal the wound left when Paige outpitched him several years earlier. The Monarchs beat Dean’s All Stars, 3-1. Smith took over for Paige in the seventh and allowed one run and two hits. Call sports editor Sam McKibben noted that the big leaguers were “loud and sincere in their praise of the Monarchs.” They said several of the Monarchs could play in the White majors.38

In his July 3 “Sports Potpourri” column, McKibben wrote that Paige’s “pinning back the ears of Dizzy Dean’s All-Stars has incurred the wrath of [Commissioner] Judge Landis. Word is out that he is ruling out all future games between Paige and Dean by making white parks off limits for such games. If so, it will kill the scheduled game in July at Indianapolis. There is only one Negro park, in Memphis. The clamor for Negroes in the major leagues may have something to do with it.” “Can’t have the Negro ball players showing up the whites y’know.”

Paige was not on hand for a May 30 game against the American Giants at Ruppert Stadium in Newark. Wilkinson had “loaned” him to the Homestead Grays for a game against a White all-star team at Griffith Stadium in Washington. The Grays won, 8-1, before a largely Black crowd of 22,000.

On June 14 at Cleveland, the Monarchs split a doubleheader with the Buckeyes before 2,000. The Buckeyes plated two runs off Satchel Paige in the first inning, and they held up for a 2-1 win in the initial matchup. On June 16, at Dayton’s Duck Park, Paige and Booker McDaniels teamed up to toss a 4-0 no-hitter against the Frigidaire Icemen. Paige worked the first four innings.39

Paige pitched the first five scoreless innings of a game against the Homestead Grays in Washington on June 18, 1942, before 28,000. It was the first time the Monarchs had met the Grays in 10 years. Satchel gave way to Hilton Smith, who took the 2-1, 10-inning loss.

At an exhibition matchup with the Eber-Seagrams in Rochester, New York, on June 24, Paige threw one-hit ball through five innings and contributed with his bat in a 6-1 Monarchs victory. It took 13 innings, but the Monarchs defeated the Chicago American Giants, 9-7, in Milwaukee at Borchert Field before 12,000 enthusiastic fans on June 28. Paige started and gave up seven hits and four runs before being relieved by Smith, who was credited with the win.

A promotional article in the July 3 Call announced that Paige would bring his all-stars to Louisville for a game against the House of David on July 5. “There is little doubt about the magnetic quality of Paige’s box office appeal. … And he is having one of his best seasons. … His fast hopper is jumping.” The game may not have been played as there was no further mention of it in the Call.

Paige and the Monarchs suffered a 1-0, 10-inning loss to the Memphis Red Sox at Pelican Stadium in New Orleans on July 7. The Monarchs shut out the Red Sox in both games of a doubleheader played at Rebel Stadium in Dallas on July 12 before 5,000 (11-0 and 6-0). Paige, “the magnet of the crowd,” pitched all seven innings in the first game, striking out 10, and was 3-for-4 at the plate.40

On July 17, 1942, the Monarchs met the Jefferson Barracks All Stars, who featured some former major leaguers, at Ruppert Stadium. The Army-Navy Relief Fund received 50 percent of the gate while the other 50 percent went to the Salvation Army Penny Ice Fund. The Monarchs won, 6-0. Paige started and went five, relieved by Hilton Smith. Both struck out seven. The two each allowed only one hit, and each had a hit.

An August 7 Associated Negro Press article printed in the Call cited J.L. Wilkinson’s support for Negro players in the major leagues. The Monarchs owner said he had talked with Leroy “Satchel” Paige, the pitching great of Negro baseball, about the situation in Chicago recently and said he advised the right-handed speedball artist, “[W]e certainly won’t stand in your way if you have a chance to play.” The ANP article noted that Paige was under a two-year contract with the Kansas City club and that he held decisions over Dizzy Dean, Schoolboy Rowe, and Bob Feller. It further observed that the pitching star had received as high as $2,000 for working one game and is reputed to have earned as much as $200,000 in a single year.

On August 13 Paige pitched all 12 innings at Griffith Stadium in a 3-2 loss to the Homestead Grays before a boisterous crowd of 26,000.

Paige took the loss in the first of two 1942 East-West All-Star Games, played before 45,179 at Comiskey Park in Chicago on August 16. He took the mound in the seventh with the score knotted 2-2 and surrendered the winning run. The August 21 Call blamed loose play behind him. While Satchel and four other Monarchs were at the All-Star Game the rest of the team was in Canton, Ohio, to play the House of David, winning 6-2.

On August 21 heavy rain in Cincinnati held the crowd to 5,000, but the soaked fans were treated to a 5-1 Monarchs win over the Ethiopian (now Cincinnati) Clowns. Paige pitched three innings. The two teams met again on September 1, also at Crosley Field in Cincinnati. Satchel pitched the first five innings in a 10-2 Monarchs mauling of the Clowns.

For the August 21, 1942, edition of the Call, Sam McKibben penned an article headlined “Paige Says Abolish Jim Crow and He Will Be Ready for His Major League Debut but Not Before at Any Price.” “Satchel Paige,” McKibben wrote, “doesn’t want a major league tryout, nor to play major league ball … unless two things come to pass: the complete abolition of JIM CROW on a NATIONAL scale … and he is given a contract identical to that tendered a white player getting a tryout. The white papers have been saying Paige is through. When Paige told a reporter that he wouldn’t sign a $10,000 contract with a big-league team and refused to reveal his current salary, it was written that he was receiving $40,000 a year. Satchel is an enthusiastic talker,” McKibben noted, “and I just let him talk. ‘Imagine,’ he says, ‘me living at a Negro hotel although I play with a white team. Record my feelings when dishes, out of which I eat, are broken up in my presence. How could I pitch a decent game with insulting jeers coming from spectators and even some of the players. … Just convince me that agitation can be halted and I’ll push fast balls by Joe DiMaggio. ‘Why,’ he says, ‘if the President hasn’t made southern DEFENSE plants hire, and use Negro labor in government plants, how can Judge Landis, Connie Mack or anyone make the southern white folk accept the Negro as a ball player. His training camp life in the South would be miserable … and the camps won’t be moved for one or two Negroes. What about the tryouts allegedly scheduled by the Pittsburgh Pirates. Who will ‘bell the cat’ [meaning end Jim Crow]? Will the white trainers work on a Negro to say nothing to take care of him. Indeed not. I’ve never been able to get any service out of one. Tell the reading public,’ says Satch, ‘not to believe half of what it reads that I say in the daily papers. I say to others what I am saying to you, but my statements are twisted. Negroes will never get into the major leagues because of jim crow. It’s a wonderful dream but will never come true. With the nation at war not one is going to try to abolish jim crow … and even in peace time, jim crowism will flourish. Me, I am going to stick with Wilkie, J.L. Wilkinson, Monarchs’ owner, and whoever says I am afraid I can’t make the grade … is just plain nuts. I experience enough prejudice now, why court more.’”41 The interview was conducted before the East-West game at Comiskey Park in Chicago.

Paige appeared in all four games that counted in the 1942 Colored World Series against the Homestead Grays. He was credited with a victory in the fourth game and a save in the second game. He did not figure in the decisions in the first and third games.

If the second game of the 1942 Series, played on a stormy September 10 night in Pittsburgh, had been in a White World Series, it would go down with Babe Ruth’s “called shot” in the third game of the 1932 World Series, historian John Holway has contended, as “a transcendental moment of baseball lore.”42 There are various versions of the game’s highlight: a confrontation between two of baseball’s most storied players, Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige. According to one, Paige entered the game in the seventh inning with the Monarchs leading 2-0. Two were out, and there was a Gray on first base. Satchel called first baseman Buck O’Neil to the mound and told Buck he was going to walk the next two hitters to get to Josh Gibson.

O’Neil said he told Paige, “Aw, man you gotta be crazy!”

Then Monarchs manager Frank Duncan, joined by J.L. Wilkinson (in at least one version of the story), came onto the field “waving their arms wildly.” Unable to change Paige’s mind, they shrugged, “It’s your funeral.”

With Gibson already in the batter’s box, Satchel called for the Monarchs trainer, “Jew Baby” Floyd, to bring him a foaming glass of bicarbonate of soda, which he drank and then let out a big belch.

“The bases was drunk,” Paige later recalled. To Gibson he said, “I heard all about how good you hit me. Now I fixed it for you. Let’s see how good you can hit me now.”

“I’m ready,” Josh replied testily. “Throw it.”

Satchel remembered saying to Gibson, “Now I’m gonna throw you a fast ball, but I’m not going to trick you.” Then “I wound up and stuck my foot in the air. It hid the ball and almost hid me. Then I fired.” Side-arm, knee-high. Josh, thinking curve, took it for strike one. He didn’t lift the bat from his shoulder.

“Now I’m gonna throw you another fast ball, only it’s gonna be a little faster than the other one,” said Satchel. “It was so tense you could feel everything jingling,” Paige remembered.

The last pitch was a three-quarter side-arm curveball. Satchel recalled that Josh “got back on his heels; he was looking for a fastball.” However, it was knee-high on the outside corner – strike three. “Josh threw that bat of his 4,000 feet.”

Paige said he could not remember Gibson ever paying the $5 he owed him. The Grays’ Buck Leonard always said he had no recollection of Paige walking two to get Gibson to the plate.43

The 1942 postseason saw a repeat of the Series in a pair of games in the Tidewater region of Virginia. On October 2 Paige hurled the first three innings, allowing one run, in the game played in Norfolk, Virginia. The Grays’ bats came alive when Connie Johnson took the mound for the Monarchs, and Homestead won 8-5. Satchel also started the second game, played in Portsmouth, Virginia, on October 4, going four innings before giving way to Hilton Smith. Paige and Smith allowed only one run each. The Monarchs blasted Grays pitching for 12 runs.

What stood out for Satchel Paige during his years with the Monarchs was his relationship with J.L. Wilkinson. “Working for Mr. Wilkinson was something no man’d forget,” Paige recalled. “He was as good a boss as you could ask for. And he was a real promoter.” With Wilkie’s portable lights, Paige remembered pitching in as many as three games in one day. In one three-game stretch in the East, Paige said, he drew 105,000 fans, pitching between three and six innings each game. His speed was back, and people were talking about him more than any other pitcher – White or Black.44

Paige biographer Larry Tye called J.L. Wilkinson “the father figure that Gus Greenlee, Alex Herman, and John Page [other owners for whom Paige played] had tried and failed to be.” Paige “felt a loyalty that he had never known before to an owner, team, and city.”45 “A lover of ribs, riffs, and reporters, he found Kansas City irresistible.”46 Satchel said, “The folks in Kansas City treated me like a king and you never saw a king of the walk if you didn’t see O’ Satch around Eighteenth and Vine in those days, rubber-necking all the girls walking by.”47

According to Tye, “It was a love instantly requited. For if Satchel adored Kansas City, Kansas City loved him right back. …”48 “Wilkinson pushed Paige to buy real estate in Kansas City, the only way he ever was able to save,” Tye has observed. Satchel was 35 when he bought his first home in Kansas City – on Twelfth Street, high on a terrace, with 14 rooms, and plenty of space for his cars, guns, and antiques as well as “a backyard big enough for hundreds of chickens, a dozen dogs, and a cow.”

Tye concluded that “[h]ome ownership had precisely the effect on Satchel that Wilkinson had hoped: It settled him down. He would remain a devoted Monarch for as long as he remained in the Negro Leagues and a devotee of J.L. Wilkinson as long as he lived.” As Satchel told the Pittsburgh Courier in 1943, his contract-jumping days were over. “I am going to play with the Kansas City Monarchs as long as the owner and manager will have me.”49

Satchel filled his house “with Chippendale chairs and roomfuls of trophies and guns.” Not surprisingly, it was Wilkinson, whose wife, Bessie, had owned an antiques store in Kansas City since 1931, who led Paige into the world of collecting, and Satchel took to it with the same gusto he had for hunting and fishing. Someone told him that in his first couple of years what he had collected was worth $20,000.50

Paige benefited from Wilkie’s promotional acumen, but, as he always had been, Satchel continued to be his own best publicist. In a July 24, 1943, Chicago Defender column, Frank “Fay” Young described a conversation he had had with Paige. Satchel was recalling that he had beaten Bob Feller in two of three games, winning the rubber game 6-3. He said Dizzy Dean had quit trying to outpitch him, as Satchel had won all but one of the games in which they had met.51

By 1945 others were noting the effect Wilkinson was having on Paige. In a May 16, 1945, Philadelphia Tribune column, Dr. W. Rollo Wilson observed that Satchel had changed his prima donna lifestyle since recovering from his arm problems and playing with the Monarchs. “He retained the on-duty color and slugged off the off-duty trimmings,” Wilson wrote. “Now, he travels with his fellows, in uniform every day and is on the field for all pre-game activities. The snob is now a regular fellow.”52

Intent on getting his moneymaker to as many appearances as possible, in June 1946, J.L. Wilkinson leased a two-seat, single-engine Cessna. The pilot was his son, Dick, who had been captain of a B-24 Liberator bomber on multiple missions during World War II. “Satchel Paige” was stenciled on the side of the Cessna. The day after the plane was delivered, Dick flew Paige from Kansas City to Madison, Wisconsin, without any problems. On the return flight, however, they encountered a storm system and bounced up and down all the way to Kansas City. “You trying to kill me! Get me out of here!” Paige yelled at Dick. Although he said he would never fly again, Paige relented (after Dick told him he would lose $500) and flew to Oklahoma. Again, the first leg of the flight was fine, but mechanical trouble made for a hectic return to Kansas City. After only two flights, the Cessna was returned to its owner when Paige let it be known in no uncertain terms that he would not fly in it again. According to Satchel, that was the last time he flew in a little plane. Wilkie didn’t force the issue.53

According to Paige, after J.L. Wilkinson “decided to kind of retire” and Tom Baird was his boss, Satchel took a sizable pay cut from the Monarchs for the 1948 season. As attendance dropped, so did his income, since he was getting a percentage of the gate on top of his salary. Even though he was almost 42 years old he still thought he was “too young to take any cut in pay.”54

During the summer of 1948 Paige was on a barnstorming tour in Iowa with his All-Stars when Dick Wilkinson, who was traveling with the team, said he got a phone call from J.L. in Kansas City. Dick recalled years later: “Dad called me on the phone and said, ‘The majors want Satch to report to Cleveland.’ I walked over to Satchel and said, ‘You’re going to the majors. Dad says get home.’ He looked at me with a big grin and said, ‘Oh boy!’ He jumped into his Cadillac and took off. That’s the last time I saw Satchel.”55

According to Paige, the first indication that he would be signed by the Cleveland Indians came in a letter from promoter Abe Saperstein, owner of the Harlem Globetrotters basketball team, who told him that Bill Veeck was looking for pitching help. Saperstein recommended Satchel and Veeck brought him to Cleveland for a tryout on July 7, Paige’s 42nd birthday. Manager Lou Boudreau caught Satchel as Paige hit the strike zone on 46 of 50 throws.

Veeck signed Paige the same day and gave the former Monarch a $10,000 signing bonus and $5,000 a month – a total of $25,000 for the season. After Satchel told Veeck that he thought Mr. Wilkinson and Mr. Baird should get something for taking him on when his arm went dead, the Indians owner agreed to give them $5,000 (according to Paige, or $15,000 in other sources) for his contract. Veeck also gave Abe Saperstein $15,000 as a finder’s fee ($10,000 according to some sources).56

In its overview of Paige’s career, the National Baseball Hall of Fame describes Satchel’s start in the majors: “At the age of 42, Paige made his big league debut when Bill Veeck signed him to a contract with the Indians on July 7, 1948. Two days later, he made his debut for a Cleveland club involved in one of the tightest pennant races in American League history. That summer and fall, Paige went 6-1 with three complete games and a save and a 2.48 earned-run average. Cleveland won the AL pennant in a one-game playoff against [the] Boston [Red Sox], then captured the World Series title in six games against the [Boston] Braves. Paige became the first African-American pitcher to pitch in the World Series when he worked two-thirds of an inning in Game 5.”57 Most importantly for the Indians and Paige, the turnstiles were twirling. More than 200,000 showed up to see Paige’s first three major-league starts, and the crowds continued.58

Bob Feller said of his Indians teammate, “He could throw the ball through a keyhole and did. …”59 However, the aging Paige could not sustain that high level of performance. After a disappointing 4-7 record for the Indians in 1949 (which Satchel attributed to a return of his stomach trouble) and the sale of the team by Bill Veeck, Paige was offered a contract for the 1950 season of $19,000 by Hank Greenberg, the new controlling owner of the Cleveland club. It was $6,000 less than his 1949 contract.

Satchel asked his wife, Lahoma, what he should do, and she said, “Maybe we’d better see Mr. Wilkinson. He’ll know. Maybe he can tell us what to do.”

Paige contacted Wilkinson at home where the retired Monarchs owner was spending most of his time since he’d sold his share of the team. When Satchel went to see him, Wilkie said, “[Y]ou’d better accept. Negro baseball and barnstorming aren’t what they used to be, not with the major leagues open now. You’d be better off with that steady job. Maybe you’d make more barnstorming, but maybe you wouldn’t.”

“I’ll sign the contract, then,” Satchel said.

“Call them up and let them know,” Wilkinson advised him. “You’ve had that contract a couple of weeks now without letting them know anything. It might be better to call.”

Paige called Hank Greenberg. It seemed settled, but Greenberg called back and told Paige that manager Boudreau had told him that he couldn’t use Satchel. In late January 1950, Greenberg announced the release of Paige, saying, “[o]lder players will have to make way for rookies.”60 Satchel was officially let go from the team on February 17, 1950.

Paige called Wilkinson and asked, “Can you get me some work? I ought to be worth something barnstorming after those two years in the major leagues.”

“Do you want to hook up with a team?” Wilkinson asked him.

“No,” Paige responded, “I don’t want’a get tied down. I want to stay loose so those big boys can call me if they want me.”

“I’ll see what I can do about booking you independent, then,” Wilkinson told him. Wilkie contacted Eddie Gottlieb and Abe Saperstein, whom Paige considered “pretty fair promoters and real sharp.” Pitching offers started coming in fast.

“It looks like you have some good jobs coming up, Satchel,” Wilkinson told him.

“When do I start?” Paige asked.

“In a couple of days. I’ve gotten a hold of a reporter and he wants to come around to talk to you. It’ll help us get more bookings. You going to be home?” Paige told him he was home, babysitting his two girls until Lahoma returned. Wilkinson and the reporter arrived about an hour later.61

When Bill Veeck purchased the St. Louis Browns in 1951, he made good on his promise to give Paige a job if he was able to acquire a new team. Satchel’s record for the year was 3-4. When it was rumored that Paige was being offered a salary of $22,000 for the 1952 season, he retorted that he had “made lots more in 1950 barnstorming for J.L. Wilkinson, my manager, and Eddie Gottlieb.”62 However, Paige would continue to pitch with the Browns through 1953 and was selected to play in two All-Star Games (1952 and 1953).

Satchel went back on the road and, by 1961, according to his own estimate, he had pitched in more than 2,500 games, winning about 2,000. He claimed he had pitched as many as 153 games a year. On September 25, 1965, at the age of 58, Paige appeared one last time in a major-league game, appropriately for the Kansas City Athletics, pitching the first three innings. In 1967 he toured for the Indianapolis Clowns for $1,000 a month. The next year illness kept him home. Satchel worked briefly as a sheriff’s deputy in Kansas City, and ran unsuccessfully for the Missouri legislature, before, in 1968, the Atlanta Braves took him on as a coach so he could qualify for a major-league pension. He died in Kansas City on June 8, 1982, a month before his 76th birthday.

Satchel Paige was, as a Collier’s writer put it, “one of the last surviving totally unregimented souls.” To paraphrase Paige himself, he did as he did. According to two of the greatest hitters of all time, Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams, Satchel was the best pitcher they’d ever seen.63

Satchel was in a class by himself in terms of what he was paid, as he was in so many other respects. During the best years of Black ball, he regularly made $30,000 to $40,000 a year. Far behind was the next highest player – Josh Gibson – who made about $1,000 a month during his peak period in the early 1940s. The secret, of course, was Satchel’s drawing power as the best pitcher of his time, as well as a master showman. He negotiated bonuses and special deals because the mere announcement that he would appear at a game meant an additional 5,000-10,000 tickets sold in the bigger parks.64

Though he was schooled in a reformatory, Paige bought a typewriter and wrote drafts of his autobiography, a 96-page version in 1948 (Pitchin’ Man) and a 300-page 1962 version (Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever). He did collaborate with Hal Lebovitz in the writing of the first and David Lipman in the second, but the two works reflect Satchel’s voice and perspective. “Unlettered yes, but not unlearned,” his biographer Larry Tye has suggested.65

In another well-researched biography of Paige, historian Donald Spivey linked J.L. Wilkinson, Abe Saperstein, Bill Veeck, and Satchel Paige as “the four [who] together wrote in bold and bright ink for future generations the how-to book of promoting professional team sports and marquee athletes. …” They also showed that “black and whites could work together for mutual self-interests in professional athletics. …”66

Buck O’Neil said, “Satchel was a comedian. Satchel was a preacher. Satchel was just about everything. We had a good baseball team, but when Satchel pitched, a great baseball team. The amazing part about it was that he brought the best out in the opposition, too.”67 O’Neil had more stories to tell about Paige than any of the countless other ballplayers, Black and White, he had known. One is particularly moving. When the Monarchs were on the road in Charleston, South Carolina, Satchel said to O’Neil, “Nancy [the nickname Satchel had given Buck, but that’s another story], c’mon with me. We’re gonna take a little trip.” They went to Drum Island, where slaves had once been auctioned off, and there was a big tree with a plaque on it, marking where the slave market was. Buck and Satchel stood there in silence, for about 10 minutes. Finally, Satchel said, “Seems like I been here before.” And O’Neil said, “Me too, Satchel.” Buck wanted it known that Paige was “a little bit deeper than most people thought.”68

Robert Leroy “Satchel” Paige was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1971 as the first selection of the Committee on Negro Baseball Leagues. When word filtered out that the Hall of Fame planned to put Paige’s plaque and those of any future Negro Leagues inductees in a special exhibit rather than the hall where the plaques of White major-league Hall of Famers were displayed, Paige retorted, “[B]aseball has turned [me] from a second-class citizen into a second-class immortal.”69 The public outcry was so great that the decision was reversed and Paige’s Hall of Fame plaque and those of subsequent Negro Leaguers selected for the Hall were placed in the same room as those honoring Christy Mathewson, Babe Ruth, and Jackie Robinson.

WILLIAM A. YOUNG is professor emeritus of religious studies at Westminster College, Fulton, Missouri. He is the author of J.L. Wilkinson and the Kansas City Monarchs: Trailblazers in Black Baseball (McFarland, 2016), for which he received a SABR Research Award (2018). Young has also written John Tortes “Chief” Meyers: A Baseball Biography (McFarland, 2012), and several books on the world’s religions. He is a member of SABR and resides with his wife, Sue, in Columbia, Missouri.

Sources

An earlier version of this essay appeared in William A. Young, J.L. Wilkinson and the Kansas City Monarchs: Trailblazers in Black Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2016).

In addition to the articles cited from the Kansas City Call, other Kansas City Monarchs game reports are drawn from a timeline for the 1942 season compiled by Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Leroy “Satchel” Paige, as told to David L. Lipman, Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever; A Great Baseball Player Tells the Hilarious Story Behind the Legend (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993), 92.

2 Roger Kahn, Rickey and Robinson: The True, Untold Story of the Integration of Baseball (New York: Rodale, 2014), 59.

3 Paige, 97.

4 Tom Dunkel, Color Blind: The Forgotten Team That Broke Baseball’s Color Line (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2013), 240.

5 Buck O’Neil with Steve Wolf and Daniel Conrads, I Was Right on Time (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), 105.

6 Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 73.

7 Janet Bruce, The Kansas City Monarchs: Champions of Black Baseball (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1985), 93.

8 Kansas City Call, March 11, 1949.

9 Paige, 130-131.

10 John B. Holway, Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues (New York: Dover, 2010 [originally published 1975]), 87; John B. Holway, Black Ball Stars, Negro League Pioneers (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler, 1988), 339-40.

11 Interview with Bill “Plunk” Drake conducted by Dr. Charles Korr and Dr. Steven Hause (December 8, 1971), Negro Baseball League Project, https://shsmo.org/stlouis/manuscripts/%20transcripts/s0829/t0067.pdf.

12 Larry Tye, Satchel: The Life and Times of an American Legend (New York: Random House, 2009), 144.

13 John B. Holway, Black Diamonds: Life in the Negro Leagues from the Men Who Lived It (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Books, 1989), 21.

14 Holway, 1988, 339.

15 Fay Vincent, The Only Game in Town: Baseball Stars of the 1930s and 1940s Talk About the Game They Loved (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006), 88.

16 Tye, 123.

17 Paige, 132.

18 Donald Spivey, “If You Were Only White”: The Life of Leroy “Satchel” Paige (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2012), 168-69.

19 Bruce, 93-94.

20 Vincent, 88-89.

21 Tye, 126.

22 Vincent, 88-89.

23 Spivey, 169.

24 Kansas City Call, September 29, 1939.

25 Spivey, 176.

26 Spivey, 176.

27 Mark Ribowsky, A Complete History of the Negro Leagues (New York: Birch Lane Press, 1995), 231-32; Tye, 145.

28 Tye, 146.

29 Charles C. Alexander, Breaking the Slump: Baseball in the Depression Era (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), 235.

30 Lanctot, 105-06.

31 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 153-71.

32 Ribowsky, 237.

33 Holway, 1989, 21.

34 Holway, 1989, 22.

35 Time, June 30, 1940: 44; Saturday Evening Post, July 27, 1940: 79-81. Cited in Alexander, 233-34, and Lanctot, 227.

36 Frazier “Slow” Robinson, with Paul Bauer, Catching Dreams: My Life in the Negro Baseball Leagues (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1999), 37-38.

37 Kansas City Call, May 1, 1942.

38 Kansas City Call, May 29, 1942.

39 Kansas City Call, June 19, 1942.

40 Kansas City Call, July 17, 1942.

41 Sam McKibben, “Paige Says Abolish Jim Crow and He Will Be Ready for His Major League Debut but Not Before at Any Price.,” Kansas City Call, August 21, 1942.

42 John B. Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History (Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House, 2001), 398-99.

43 Sources for the 1942 Colored World Series: Kansas City Call, September 18 and 25; Holway, 2001, 398-99; Ribowsky, 258-62; Robinson, 93, 95; Bruce, 103-04; Luke, 91-92; Paige, 146-47, 152; O’Neil, 126-38; James A. Riley, Of Monarchs and Black Barons: Essays on Baseball’s Negro Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012), 153.

44 Paige, 138-139.

45 Tye, 137.

46 Tye, 137.

47 Tye, 142.

48 Tye, 137.

49 Cited by Tye, 166.

50 Tye, 136-38, 165-66. See also Robinson, 50; Paige 1993: 142, 168-69; Larry Lester and Sammy Miller, Black Baseball in Kansas City (Charleston, South Charleston: Arcadia, 2000), 103; Interview with Richard “Dick” Wilkinson conducted by Janet Bruce (October 1, 1979). Kansas City Monarchs Oral History Collection (K0047), Tape No. A0016-17. State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Kansas City.

51 Frank “Fay” Young, Chicago Defender, July 24, 1943.

52 Jim Reisler, Black Writers, Black Baseball: An Anthology of Articles from Black Sportswriters Who Covered the Negro Leagues, revised edition. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2007), 128.

53 Kansas City Call, July 5, 1946; Spivey, 199, 209-11; Paige, 75-78; Thomas Fredrick, “KC Connection Began Baseball’s Globalization,” Kansas City Star, October 16, 2004: C6 (J.L. Wilkinson File, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York).

54 Paige, 195.

55 Tye, 205.

56 Paige, 196-98. See also Tye, 217-18; Lanctot 335-36.

57 baseballhall.org/hof/paige-satchel.

58 For Paige’s vivid description of his Indians debut, see Paige, 200-205.

59 Interview with Bob Feller conducted by Fay Vincent; Vincent, 51.

60 Spivey, 246; Tye, 264.

61 Paige, 234-35.

62 Spivey, 250.

63 Dunkel, 277.

64 Robert Peterson, Only the Ball Was White (New York: Oxford University Press), 120-21.

65 Tye, 288-89.

66 Spivey, xix-xx.

67 Dunkel, 70.

68 O’Neil, 100-101.

69 O’Neil, 222.