1959 White Sox in Literature: Haunted by Ghosts of the Black Sox

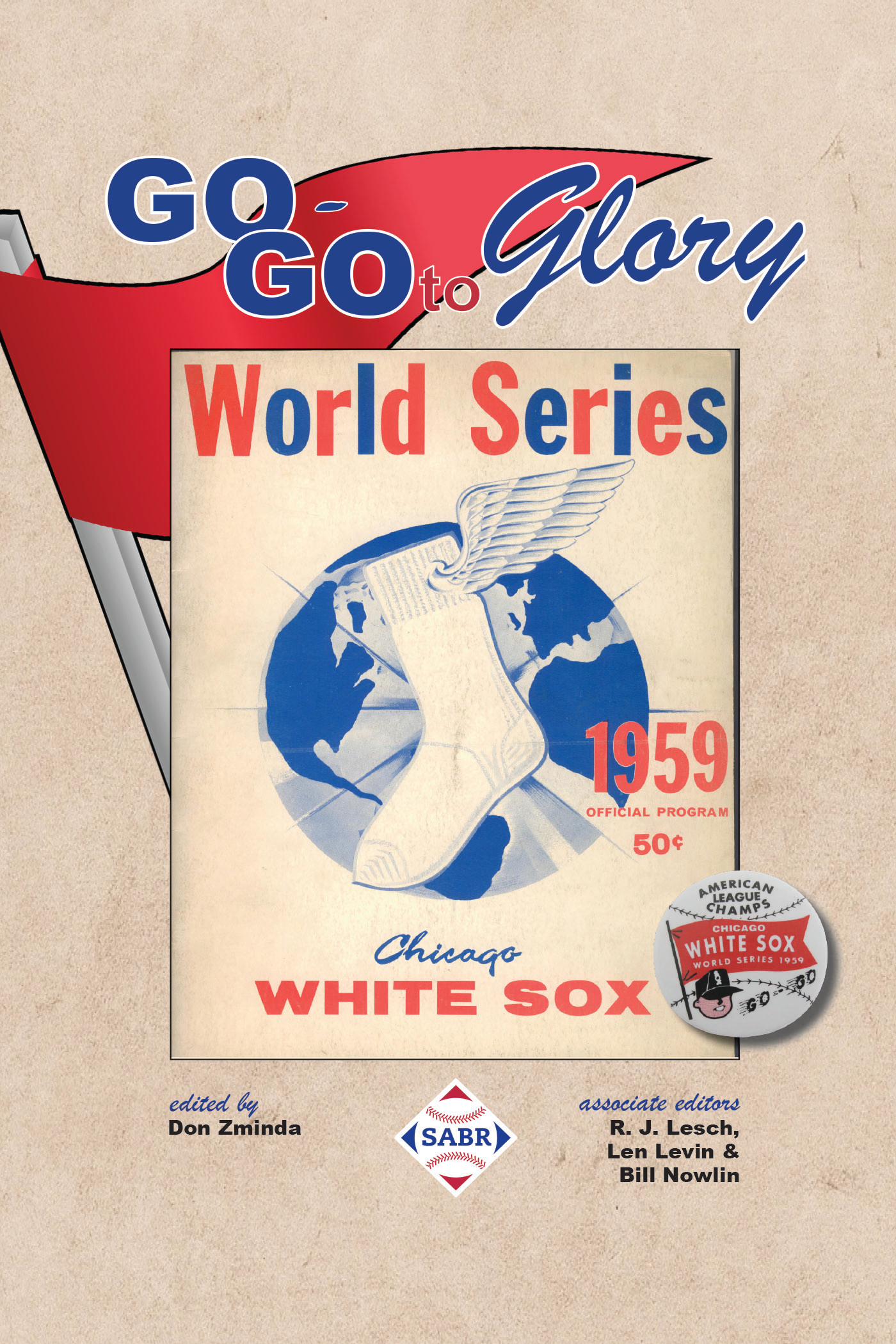

This article appears in SABR’s “Go-Go to Glory: The 1959 Chicago White Sox” (2019), edited by Don Zminda.

As a franchise, the Chicago White Sox have had a colorful history. With all the organization has endured over the years, some may consider them the most literary of professional baseball teams. Great 20th century writers such as James T. Farrell and Nelson Algren were raised Sox fans on Chicago’s South Side, and when writing about the game of baseball, they focused on their childhood heroes. Contemporary Chicago writers including Stuart Dybek and Tony Fitzpatrick also depict the White Sox in their fiction and poetry. But this sunny loyalty has an inevitable shadow: the Black Sox of 1919. Just as any depiction of the New York Yankees evokes the spirits of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, any mention of the White Sox calls forth the troubled ghosts of Shoeless Joe Jackson and Eddie Cicotte.

As a franchise, the Chicago White Sox have had a colorful history. With all the organization has endured over the years, some may consider them the most literary of professional baseball teams. Great 20th century writers such as James T. Farrell and Nelson Algren were raised Sox fans on Chicago’s South Side, and when writing about the game of baseball, they focused on their childhood heroes. Contemporary Chicago writers including Stuart Dybek and Tony Fitzpatrick also depict the White Sox in their fiction and poetry. But this sunny loyalty has an inevitable shadow: the Black Sox of 1919. Just as any depiction of the New York Yankees evokes the spirits of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, any mention of the White Sox calls forth the troubled ghosts of Shoeless Joe Jackson and Eddie Cicotte.

For baseball fans, as William Faulkner said in a different context, “The past isn’t dead. It isn’t even past,” and no other event in baseball history has generated as many historical investigations and literary representations as the Big Fix and the Black Sox Scandal. Writers and film-makers like Eliot Asinof, John Sayles, W. P. Kinsella, and Phil Alden Robinson have ensured that the Black Sox remain part of the contemporary American baseball narrative, with books and films including Eight Men Out, Shoeless Joe, and Field of Dreams introducing new generations to the story.

Therefore, when the White Sox of 1959 went to the World Series against the Los Angeles Dodgers, it was more than just the second time in a decade that Al Lopez had figured out how to wrest the American League pennant out of the Yankees’ grasp. Chicago’s first fall classic in 14 years (since Charlie Grimm’s ’45 Cubs) was haunted by the ghosts of that 1919 team, 40 years gone. After the Sox’ pennant-clinching victory in Cleveland, an anonymous scribe in the Chicago Sun-Times led his story with the Black Sox:

Forty years of frustration, dating back to the Black Sox scandal, has ended with the White Sox winning the American League pennant. From the time the late Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis banished eight Sox players from baseball for allegedly throwing the 1919 World Series to Cincinnati, the White Sox have struggled through three generations to field another winner.1

A few days later, writing about the media coverage of the event, Fletcher Wilson informed his readers in the same paper that two of the men who would be overseeing the Western Union wire services from the series had “worked the keys” as telegraph operators during the 1919 Series. A more physical connection was made as the ceremonial first pitch of Game One was thrown by Red Faber to Ray Schalk, each of whom had played on both the 1917 White Sox World Series championship team, and were among the “Clean Sox” of 1919.2

However, as much as baseball tried to clean up its act, the dark side of the game remained. For example, even though Arnold Rothstein was long dead, gambling remained a part of American sporting culture and baseball was still America’s premier sport. Chicago reporter Art Petacque kept Sun-Times readers up to date with the odds that bookies – both the local mobsters and those from the Chicago Outfit’s farm team in Las Vegas – were giving on the ’59 Sox.

Chicago’s bookmakers, a notoriously unsentimental fraternity, have picked the White Sox to win the World Series. On the eve of the opening game, the books were laying 6-5 odds that the Sox would win not only the first game but the world championship as well.3

Petacque also reported that scalpers were unhappy with Sox owner Bill Veeck’s decision to sell Series tickets by mail order only, preventing them from scooping up large blocks of tickets. “We’ve waited 40 years for an opportunity like this, and then Veeck had to do this to us,” one complained. A Chicago police commander, part of whose job was running scalpers off, told reporter Jack McPhaul, “In 1919 when the Sox last won a pennant, he played hooky from school, got to the bleachers at dawn, and saw the game.”4 And Andy Frain, the legendary usher, had sold seat cushions in 1919, though in 1959 he was mostly worried about keeping people without tickets from getting into the stadium. In another un-bylined article, he listed the strategies his men guarded against. The article ends with a reference to the decades since the Black Sox: “Frain was worried,” he said, “that Chicagoans may have dreamed up some gate-crashing techniques unknown even to him. After all, they’ve had 40 years to think about it.”5

Chicago writer Nelson Algren had thought about the Black Sox a lot for those 40 years. In his 1951 prose poem, Chicago: City on the Make, he recounts the effect of the scandal on his childhood. He was 11 years old when the scandal broke, newly moved from the Far South Side, across the great divide in Chicago identity from White Sox country to “North Troy Street [which] led, like all North side streets – and alleys too – directly to the alien bleachers of Wrigley Field.”6 Algren was a regular book reviewer for the Sun-Times and he wrote three stories about the Series, after the first, second and sixth games: “Nelson Algren Writes Impressions of Series,” “Algren Writes of Roses and Hits,” and “Nelson Algren’s Reflections: Hep-Ghosts of the Rain.” Throughout these stories, and in their later more literary iteration, Algren returns to the Black Sox to contextualize and understand the events of the ’59 Series, both the positive and the negative.

Algren began his first piece with memories of his childhood, when he sneaked into a Sox game, thus acquiring the appropriate nickname – Swede – from the other baseball-crazed boys of the neighborhood. By 1959, he still felt like that child who rooted for Swede Risberg, ignorant of the player’s perfidy, yet somehow guilty by association. He wrote, “I had come to the park assuming there would be a roped-off area for Black Sox fans paroled for the series, and really began to enjoy being there right in the middle of the first class citizens.” But these first-class citizens, Algren suggests, might not be the best of baseball fans, as he mocks fans ignorant of the game. “One woman asked her husband what the score was and he told her ‘11 to nothing in the fourth, dear,’ he says. I actually heard her ask, ‘Does that mean it will be 22 to nothing in the eighth?’” He concludes with a slight jab at Bill Veeck, famous for trying to pack his ballparks: “I left after the Dodger half of the seventh and the attendance hadn’t been announced; so I assume they were still selling tickets.”7

In his second story, the Black Sox played a lesser role. After the Sox routed the Dodgers in the first game, Algren and many other Sox fans thought the series was a lock, and he opened by joking that “the Dodgers might return to Los Angeles, or Brooklyn, or wherever they come from, without playing it out.”8 Shoeless Joe makes a brief appearance, along with Eddie Gaedel, as Algren tells tall tales to distract a female fan from the Dodgers’ 4-3 victory. The sense of wistful melancholy from the first story evaporates.

After the Series is over, however, Algren returns to the Black Sox. His own sense of a past began, he writes, when “on the last afternoon of summer I saw Shoeless Joe Jackson leave his glove in left field, walk toward the darkening stands and never come back for his glove.”9 Algren’s reflections on the series conclude with an evocation of the ghosts of Chicago’s hustlers, haunting the poolrooms and El trains:

I have seen the ghosts of the blue-moon hustlers leaping drunk below the all-night billboard lights.

Yesterday evening, when the crowd was gone and I stood up at last to leave, I saw the shade of Shoeless Joe.

He was walking toward the darkening stands, and he’d left his glove behind.10

For Algren the sadness of a World Series defeat was best expressed by connecting back to the sorrow of not just the defeat, but the betrayal, of 1919. The tragic past isn’t dead; it isn’t even past.

Yet in his prose and poetry about the Black Sox, Algren may perhaps have begun the rehabilitation of Shoeless Joe Jackson, from criminal to redemptive hero in Field of Dreams. Another writer, Daniel Nathan, has written about the transformation of depiction of the Black Sox players from criminals or traitors to tragic victims of greedy gamblers and venal ownership in Saying It’s So: A Cultural History of the Black Sox Scandal. Algren was perhaps the first major writer to engage in this shift when he wrote in Chicago: City on the Make about his childhood defense of Shoeless Joe: “Out of the welter of accusations, half denials and sudden silences a single fact drifted down: that Shoeless Joe Jackson couldn’t play bad baseball even if he were trying to. He hit .375 in that series and played errorless ball, doing everything a major-leaguer could to win.”11 His newspaper stories on the ’59 Sox continued to depict the Black Sox as tragic victims rather than criminals.

As a writer, Algren’s method always involved reworking old materials. He combined his ’59 Series pieces, and revised them into “Go! Go! Forty Years Gone,” published in The Last Carousel, his 1973 collection of fiction, journalism, and poetry (including “Ballet for Opening Day: Or, the Swede Was a Hard Guy,” his retelling of the Black Sox story.) In this revision Algren edits to somewhat de-emphasize the story of being at the game, and to increase the sense of nostalgia and melancholy associated with having been a White Sox fan at a time of scandal leading to a sense of betrayal, a sense of possibilities forever forgone. He depicts the ’59 White Sox team almost entirely through the lens of the Black Sox.

Had the ’59 Sox beaten the Dodgers, perhaps the Black Sox would have faded further into the past. But instead of erasing 1919, the 1959 season echoed it: another loss, bitter in the mouths of South Siders and Chicago writers. Not a thrown Series, but not a triumph to erase that still-fresh and endlessly rehashed ignominy either.

Finally, in 2005, White Sox manager Ozzie Guillen would follow in the footsteps of Lopez, and then take one step further. Winning the 2005 World Series, the White Sox added another chapter to the long narrative of White Sox and Chicago baseball. However, in all the press coverage of that magical season, local and national media could not help but refer to the Black Sox, nodding only in passing to the ’59 squad. Hopefully, with this book, the 1959 team can take its rightful place in the history of this storied franchise.

BILL SAVAGE is a Professor of Instruction in the Department of English at Northwestern University, where he teaches the course “Baseball in American Narrative,” which focuses on the ways that baseball stories create a sense of American identity. He has co-edited two editions of the work of Nelson Algren: The 50th Anniversary Critical Edition of The Man with the Golden Arm, and Chicago: City on the Make, Newly Annotated. A member of the Society for American Baseball Research, he is a lifelong resident of Chicago’s North Side, and a die-hard fan and season ticket holder for the Chicago Cubs. But he believes, despite evidence to the contrary, that Cubs and Sox fans can get along, and he acknowledges that the White Sox are the much more literary team. He wrote a column about the 2016 Cubs World Series run for ESPN.com, “The View from Section 416.”

Sources

Algren, Nelson. Chicago: City on the Make (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001). Newly Annotated, Schmittgens and Savage, editors.

—–-. “Go-Go Forty Years Ago,” The Last Carousel (New York: Putnam’s, 1973).

—–-. “Ballet for Opening Day: Or, The Swede Was a Hard Guy,” The Last Carousel. New York: Putnam’s, 1973.

Anonymous. “‘We’ll Win in 4 Games,’ Beams Daley,” Chicago Sun-Times, October 1, 1959.

McPhaul, Jack. “Sox Fans See–And They Believe,” Chicago Sun-Times. October 2, 1959.

Nathan, Daniel. Saying It’s So: A Cultural History of the Black Sox Scandal (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2003).

Notes

1 “Sox Victory Ends 40-Year Famine,” Chicago Sun-Times, September 23, 1959.

2 Fletcher Wilson, “600 Writers Here to Cover Classic,” Chicago Sun-Times, October 1, 1959.

3 Art Petacque, “Who’ll Win? Sox, by All Odds,” Chicago Sun-Times, October 1, 1959.

4 Petacque.

5 “They Shall Not Pass! Frain Stands Guard at the Gates,” Chicago Sun-Times, October 2, 1959.

6 Nelson Algren, “The Silver-Colored Yesterday,” from Charles Einstein, ed. The Fireside Book of Baseball, edited by Charles Einstein (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1956), 3.

7 Nelson Algren, “Nelson Algren writes Impressions of Series,” Chicago Sun-Times, October 2, 1959.

8 Nelson Algren, “Algren Writes of Roses and Hits,” Chicago Sun-Times, October 3, 1959.

9 Nelson Algren, “Nelson Algren’s Reflections: Hep-Ghosts of the Rain,” Chicago Sun-Times, October 10, 1959

10 Algren, “Nelson Algren’s Reflections.”

11 Algren, “The Silver-Colored Yesterday,” 4.