Ty Cobb’s Last Hurrah: The 1928 Japan Tour

This article was written by Tom Hawthorn

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1907-1958

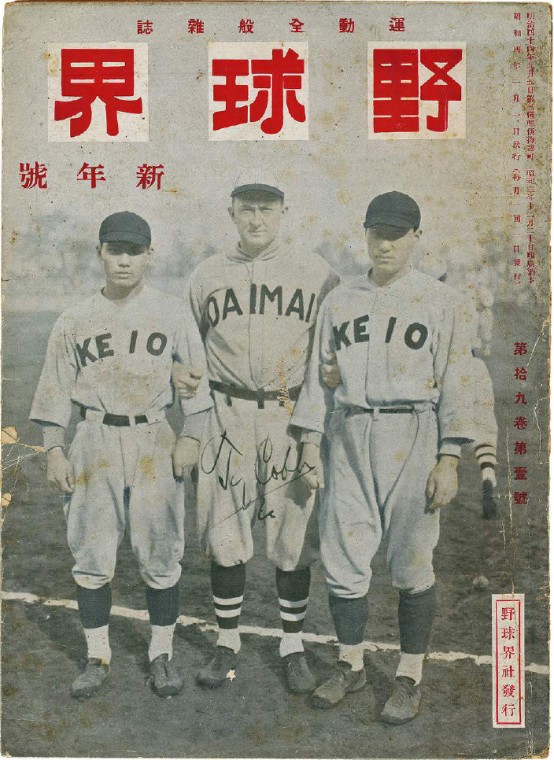

Cover of the January 1929 issue of Yakyukai showing Ty Cobb with Keio players Takayoshi Okada and Saburo Miyatake (Coutesy of Robert Klevens, Prestige Collectibles)

On an off-day on the road in Cleveland, Tyrus Raymond Cobb, hailed for much of his career as the greatest player the game had ever known, announced his impending retirement. It was September 17, 1928. He had last been a starter in late July when he batted second for the Philadelphia Athletics before trotting out to right field. He went 2-for-5 that day with a single and a double, scoring what would be the winning run in a 5-1 game on a passed ball. Since then, he had been used sparingly as a pinch-hitter, going 1-for-9.

The Georgia Peach was in his 24th season, a 41-year-old man who was now caught stealing more often than not. He appeared in only 95 games for Connie Mack’s team. While his .323 batting average was far from disgraceful, it was still his poorest performance in two decades.

Many of his younger teammates spent the rare offday at the racetrack. Cobb invited reporters to gather in his room at the glamorous Hollenden Hotel, where he handed each of them a typewritten statement in which he announced his retirement even “while there still may remain some base hits in my bat.”1 The player spoke informally with the writers for hours, examining his career (he called Carl Weilman the toughest pitcher he faced) and expressing a desire to do nothing but enjoy his family’s company for a year. The only item on his agenda was some winter hunting near his home in Augusta, Georgia.

“I am just baseball tired and want to quit,” Cobb said. “I will be leaving baseball with a lot of regrets and still with a light heart. It’s hard to pull away from a game to which one has given a quarter-century of his best manhood and which paved the road to lift me to a place of prominence and affluence.”2

He had been for a time the highest-paid player in the game, earning nearly a half-million dollars in salary over the seasons, while investments in a car company later absorbed by General Motors, as well as in Coca-Cola from his home state, ensured that he faced few future privations.

The news of his pending retirement was greeted by newspapers as the passing of an era.

“He is worth more than a million dollars,” noted the Morning Call of Allentown, Pennsylvania, “and is not worrying about his future or the price of pork chops.”3 The newspaper predicted that he might become a minority owner of a franchise in the high minors.

Cobb recorded his 4,189th hit, a double, against the Washington Senators as a pinch-hitter on September 3. He played what would be his final game in the majors eight days later, popping out to Mark Koenig at shortstop to lead off the ninth in a 5-3 loss at Yankee Stadium. He would get his final two hits in an A’s uniform in Toronto in an exhibition game at Maple Leaf Stadium on September 14. Then it was on to Cleveland to sit on the bench.

For a player reputed to be ill-tempered, he was wistful about spending time with his family.

“Guess it’s time to get out of the game and play with my kids before they grow up and leave me,” he said in announcing his pending retirement. “And there’s that trip to Europe that I promised Mrs. Cobb this year.”4

His wife, Charlotte Marion Lombard, known as Charlie, did not get to see Europe in 1928. Three weeks after the hotel room session to announce his retirement, Cobb was traveling through Virginia on his way home to Georgia when he told friends of plans to play baseball overseas. In Japan.

The news broke nationally on October 7 when the Associated Press carried on its wires a news item based on a Richmond Times-Dispatch story. The report said Cobb would spend seven weeks in Asia, accompanied by former pitcher Walter Johnson, the manager of the Newark Bears of the International League.

Three days later, George A. Putnam, secretary-owner of the San Francisco Seals and a friend of Cobb’s, offered further details. The player was going to give lectures on the game. He was also going to suit up and play with university teams. The tour was sponsored by the Osaka newspaper Mainichi Shimbun and four universities—Waseda, Meiji, Osaka, and Keio, whose own baseball team had toured the United States for six weeks earlier in the year.5

The Pittsburgh Press had a scoop on the pending trip by several days. Sporting editor Ralph Davis, who was in New York to cover the first game of the World Series on October 4, slipped in a final paragraph at the end of his lengthy report on the Yankees’ 4-1 victory over the St. Louis Cardinals. He noted that Cobb had popped into the press box at Yankee Stadium and mentioned that he was off to Japan later in the month with two players on a tour organized by Herb Hunter.6

Hunter, whose own major-league career as a weak-hitting infielder-outfielder lasted 39 games with four different teams, first traveled to Japan with Doyle’s 1920 All-Americans and ended up coaching at several Japanese universities after the tour. In 1922, after what was his final season as a player, he led an all-star team of players, including Waite Hoyt, Herb Pennock, Casey Stengel, and George “High Pockets” Kelly, on a successful tour of Japan, Korea, China, the Philippines, and Hawaii. Hunter would go on to become a baseball ambassador, making at least 10 goodwill trips to Japan between 1920 and 1937.7

A month before Cobb made his announcement, Hunter got a cablegram from Japan inviting him to bring over another team of major leaguers. The assignment was going to be difficult, as active players were now banned from playing exhibition games after October 31.8 Hunter hoped whatever disappointment the hosts might feel would be assuaged by bringing the greatest all-around player the game had seen. According to Cobb biographer Charles C. Alexander, Hunter offered Cobb $15,000 for his services.9

Also joining the tour were Bob Shawkey, a savvy right-hander who had gone 195-150 over 15 seasons as a starter in the majors, mostly with the Yankees. When they released him after the 1927 season, Shawkey held team records for wins, shutouts, strikeouts, and innings pitched.10 He was a pitching coach and starter with the Montreal Royals in 1928, going 9-9.

His catcher was former Yankees teammate Fred Hofmann, a 34-year-old journeyman who when once asked how he batted (right, left, or switch), responded, “Poor.”11 He was nicknamed “Bootnose” for an obvious facial feature. Hofmann hit .226 for the Boston Red Sox in 1928 in what proved to be his final major-league campaign, though he continued playing in the minors until age 43.

Joining the three players was Ernest Cosmos “Ernie” Quigley, a stocky umpire bom in the Canadian province of New Brunswick. Quigley lettered at the University of Kansas as a football player and hurdler in track and field for the Jayhawks. A limited minor-league career gave way to coaching football and officiating in three sports. By the time he retired, he estimated he had worked 400 college football games, 1,400 college basketball games (as well as the 1936 US Olympic qualifying tournament), and more than 3,000 major-league games. He officiated three Rose Bowl games and six World Series, the most notable being the one remembered as the 1919 Black Sox series.12

Tagging along were Seals owner Putnam and travel agent Frank Ploof of Tacoma, Washington, described as a sponsor of the trip. The latter, who stood nearly 6-feet tall though weighing just 150 pounds, posed for a photograph in a baseball uniform with the three players.13

After traveling across the continent to Seattle, Cobb met with Japanese consul Suemasa Okamoto and his wife. He also led his tour mates, bolstered by local players, in defeating an amateur team from West Seattle by 12-5. Cobb went 4-for-6.

The baseball tourists boarded the steamship SS President Jefferson of the American-Oriental Mail Line in Seattle on October 20, the ship departing at 11 A.M. Cobb was accompanied by his wife and three youngest children, Herschel, Beverly, and James. Quigley and Hunter were also joined by their families. Although some newspapers were still reporting that Johnson was on the tour, the old pitcher had backed out after signing days earlier to manage the Washington Senators.

The steamship’s other passengers included businessmen from railroad and automobile companies, as well as a handful of globe-trotting tourists, among them a Kansas City doctor and the former mayor of Keokuk, Iowa.14 Traveling in steerage were many former crew members from China who had just lost their jobs to Americans as part of the awarding of a contract to carry the mails. More than half of the 123 Chinese crew were to be replaced.15

The steamship sailed north through Puget Sound and across the Strait of Juan de Fuca before pulling into the Rithet Piers at Victoria, British Columbia.

As cargo and mail were loaded, Cobb took advantage of the layover to do a quick tour of the provincial capital. A large crowd of fans surrounded him. They were uncertain whether this was indeed the famous baseballer until “one youngster hollered out, ‘Hello, Mr. Cobb,’” reported the Victoria Daily Times. “The famous baseballer looked at the boy for a few seconds and then said with a smiling face, ‘Hello, Sonny, and how are you?’”16

After arriving in Yokohama, the trio of ballplayers conducted clinics with translators, while Quigley demonstrated umpiring techniques. The players donned university team uniforms and played a series of games with teams from the Tokyo Big Six League.

“Cobb couldn’t control his zest to win, even in those games,” Hunter later told The Sporting News. “Wearing the uniform of a Japanese college, he wanted to win as badly as when he was with the Tigers. And pity the young Japanese player who didn’t understand him and threw to the wrong base!”17

As many as 4,000 students attended a clinic conducted at Waseda University, staying on the field until it was so dark they could no longer see the ball. Quigley’s evening officiating classes attracted as many as 400, including officers of the imperial army. The ump found all his students to be attentive, though he felt they never mastered the balk rule.18

The 12 games in which the American players took part were well attended with crowds as large as 22,000 reported. Tickets were the equivalent of 50 cents, or about $7.50 in today’s money. Cobb played first base with Shawkey on the mound and Quigley behind the plate calling balls and strikes. (Hofmann did not play, so as to observe the major-league rule about taking part in exhibitions after October 31.) Cobb also did brief stints in the outfield and on the mound. One report on his return noted that he had surrendered just one run in 18 innings.19

Whenever Cobb appeared in public, he was mobbed by dozens of Japanese children, who trailed after him.

The visitors were feted with elaborate banquets heavy on rice and dried fish.

Cobb was one of 12,631 foreigners to visit Japan in 1928 and one of only 3,240 American tourists. Earlier in the year, a baseball team from the University of Illinois team had also toured the country.

While on their way home, Hunter sent a telegram to the Honolulu Star-Bulletin seeking to organize two games in Hawaii. As it turned out, football games were scheduled for the dates the Cobb party sought and Honolulu Stadium manager J. Ashman Beaven did not want to remove the football grandstands to make way for exhibition baseball.20

Despite the snub, the party was greeted warmly. “To the touring baseball players we extend ALOHA,” wrote William Peet, sports editor of the Honolulu Advertiser.21 A fleet of Dodge Victory cars met the boat. The players were given a tour of the city’s sites before being feted at a banquet at the year-old Royal Hawaiian, a seaside luxury hotel built on Waikiki Beach. The guest list included the governor and the mayor.22

Days after leaving Hawaii, the President Jefferson docked in San Francisco during a squall at daybreak on December 12, 1928. The 150 cabin passengers included Cobb, who on his arrival assured newsmen he was permanently retired as a player, except perhaps for the occasional exhibition. He insisted he planned on taking a year off.

“Do you know that out of my 24 years in professional baseball I have had less than 10 years with my family?” he said. “From now on I hope to be with the wife and children all the time. I’m going to travel and the family will travel with me, no mistake.”23

Cobb picked up a smattering of Japanese on the trip. On his return, a fan spotted him and asked, “It’s you, is it, Mr. Cobb?” Cobb responded automatically, “Sou desu hai, arigato.” (“So it is. Yes. Thank you.”)24

“I had a wonderful trip,” Cobb said. “I enjoyed every minute of it and they showed me a wonderful time there.”25

He offered his thoughts on the future of the sport in Japan. “What Japan needs is professional baseball. There is a lot of school and college baseball there, but after the players leave school they do not keep up baseball. A professional league there would make baseball the most popular thing in Japan.”26

Cobb marveled at the Japanese players’ fielding and speed, while noting that they were better hitters than had been described. Cobb’s opinion was shared by the others. “Japan has a great baseball future, and someday is going to be heard from in diamond annals,” Hunter said after returning from his visit. “We enjoyed our stay immensely—courteously treated all the time and the Japanese in turn seemed to enjoy us.”27

Shawkey thought his hosts not good hitters,28 though he too was impressed by their fielding and throwing. “I loved it in Japan,” he recalled decades later, “and it was amazing how keen these people were on baseball.”29 Quigley disagreed with Shawkey’s assessment as to hitting prowess.

“Don’t let anyone tell you that the Japanese cannot hit a curved ball or throw one,” he said. “I found the Japanese intensely interested in baseball. Although the game is played by college students and high school students almost exclusively, nearly everyone in Japan that we came in contact with was baseball mad.”30 Cobb’s 1928 visit would be overshadowed by more substantial tours before and after (in 1922, 1931, and 1934). A handful of souvenirs have been sold by auction in recent years, including the January 1929 edition of Yakyukai (Baseball World) magazine featuring Cobb on the cover in a Daimai uniform flanked by Takayoshi Okada and Saburo Miyatake of Keio University. The magazine sold for $345 in 2021, though much of the spine cover was missing.31 In 2019 Leland’s sold a copy for $637.20.32 In 2006 Robert Edward Auctions sold an autographed photograph of Cobb in a Tokyo uniform for $3,190,33 while two years later another autographed photo featuring Cobb in a Daimai uniform sold for $1,528.34 Yet another signed photograph showing Cobb seated in a dugout with three men was sold by Shafran Collectibles for $1,750.35

The tour ended in some acrimony. Cobb felt he had been cheated of money by Hunter, baseball writer Fred Lieb wrote in his 1977 memoir, Baseball as I Have Known It.36

After two months on the road, Cobb at last arrived home on December 18, 1928, his 42nd birthday. “Little did I think when I started playing baseball 24 years ago in Georgia,” he said, “that I would play my last game in Japan.”37

TOM HAWTHORN is a Canadian author who has written for newspapers and magazines for more than four decades. He is currently a speechwriter for the premier of British Columbia.

SOURCES

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted:

Fitts, Robert K. Banzai Babe Ruth: Baseball, Espionage, and Assassination During the 1934 Tour of Japan (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012).

Leerhsen, Charles. Ty Cobb: A Terrible Beauty (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2015).

Nowlin, Bill. “Herb Hunter,” SABR BioProject, accessed on December 11, 2022.

NOTES

1 James C. Isaminger, “Ty Cobb to Retire This Fall After 24 Years of Service,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 18, 1928: 24.

2 “Ty Cobb Will Quit at End of Season,” New York Times, September 18, 1928: 24.

3 “Connie Mack Asks Waivers on Three Veterans, Ty Cobb, Bush and Speaker,” Allentown (Pennsylvania) Morning Call, November 3, 1928: 20.

4 “Ty Cobb Will Quit at End of Season.”

5 “Cobb to Lecture to Japan Teams,” Miami Herald, October 12, 1928: 8.

6 Ralph Davis, “Yankees’ Victory Changes Sentiment,” Pittsburgh Press, October 5, 1928: 54.

7 Jimmie Thompson, “The Crow’s Nest,” The State (Columbia, South Carolina), July 7, 1943; 9. Articles in the Japan Times verify that Hunter was in the country in 1920, 1921, 1922, 1928, early 1931, late 1931, 1932, 1933, 1934, and 1935.

8 National Baseball Hall of Fame, “At Home on the Road.” Accessed January 27, 2022. https://baseballhall.org/discover-more/history/barnstorming-tours.

9 Charles C. Alexander, Ty Cobb (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984), 237.

10 Stephen V. Rice, “Bob Shawkey,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bob-shawkey/.

11 Bill Nowlin and Rory Costello, “Fred Hofmann.” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/fred-hofmann/.

12 Larry R. Gerlach, “Ernie Quigley: An Official for All Seasons,” Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 33 (Winter 2010-2011): 218-39.

13 “Ty and Others Go to Japan to Treat Natives,” Sporting News, November 15, 1928: 7.

14 “Jefferson Will Take Heavy List to Orient Ports,” Victoria (British Columbia) Daily Times, October 19, 1928: 10.

15 “Replacing Chinese,” Tacoma (Washington) Daily Ledger, October 19, 1928: 10.

16 “Ty Cobb Pays Visit to City,” Victoria Daily Times, October 22, 1928: 8.

17 Fred Lieb, “Fred Lieb and Herbert Hunter Will Carry Gospel of Major League Baseball to Japan in 1931; First Oriental Diamond Missionary Tour in Nine Years,” The Sporting News, January 1, 1931: 3.

18 “Cobb and Putnam Home After Tour of Orient,” Sacramento Bee, December 13, 1928: 27.

19 Abe Kemp, “Give Me a Line” (column), San Francisco Examiner, December 14, 1928: 33.

20 “No Game Here,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, November 16, 1928: 14.

21 William Peet, “Sport Flashes,” Honolulu Advertiser, December 6, 1928: 11.

22 “Royal Welcome Is Planned for Our Famous Visitors,” Honolulu Advertiser, December 6, 1928: 10.

23 Ed A. Charlton, “President Jefferson’s Pilot Guides Big Liner Safely Through Squall in Record Breaking Docking Here,” San Francisco Examiner, December 13, 1928: 31.

24 Russell J. Newland, “Home from Orient, Cobb Says He Has Scored His Last Run,” Atlanta Constitution, December 13, 1928: 16.

25 Pete Doster, “Georgia Peach Played Last Baseball Games During Japanese Tour,” Honolulu Star Bulletin, December 6, 1928: 14.

26 Doster.

27 “‘Herb’ Hunter Back, Sees Great Baseball Future for Nipponese,” Red Bank (New Jersey) Daily Standard January 4, 1929: 1.

28 “Japs Can’t Hit the Ball,” Syracuse Herald, January 25, 1929: 49.

29 Bill Reddy, “Keeping Posted,” Syracuse Post Standard, February 15, 1971: 15.

30 Frank Roche, “Baseball and Not Jiu Jitsu Is Most Popular Sport Now in Japan, Noted Umpire Says,” Los Angeles Times, December 17, 1928: 13.

31 https://prestigecollectiblesauction.com/bids/bid- place?itemid=5498. Date accessed: February 26, 2022.

32 https://auction.lelands.com/bids/bidplace?itemid=96124. Date accessed: February 26, 2022.

33 https://robertedwardauctions.com/auction/2006/spring/647/1928-cobb-signed-japanese-barnstorming-photo-psa/ Date accessed: February 26, 2022.

34 https://robertedwardauctions.com/auction/2008/spring/842/1928-cobb-signed-japan-tour-photo/Date accessed: February 26, 2022.

35 http://www.shafrancollectibles.com/shop/new-items/ty-cobb-1928-signed-daimai-japan-tour-photo/Date accessed: February 26, 2022.

36 Fred Lieb, Baseball as I Have Known It (New York: Coward, McCann and Geohegan, 1977), 198.

37 Doster.