The Bronx Always Beckoned

This article was written by Bob Golon

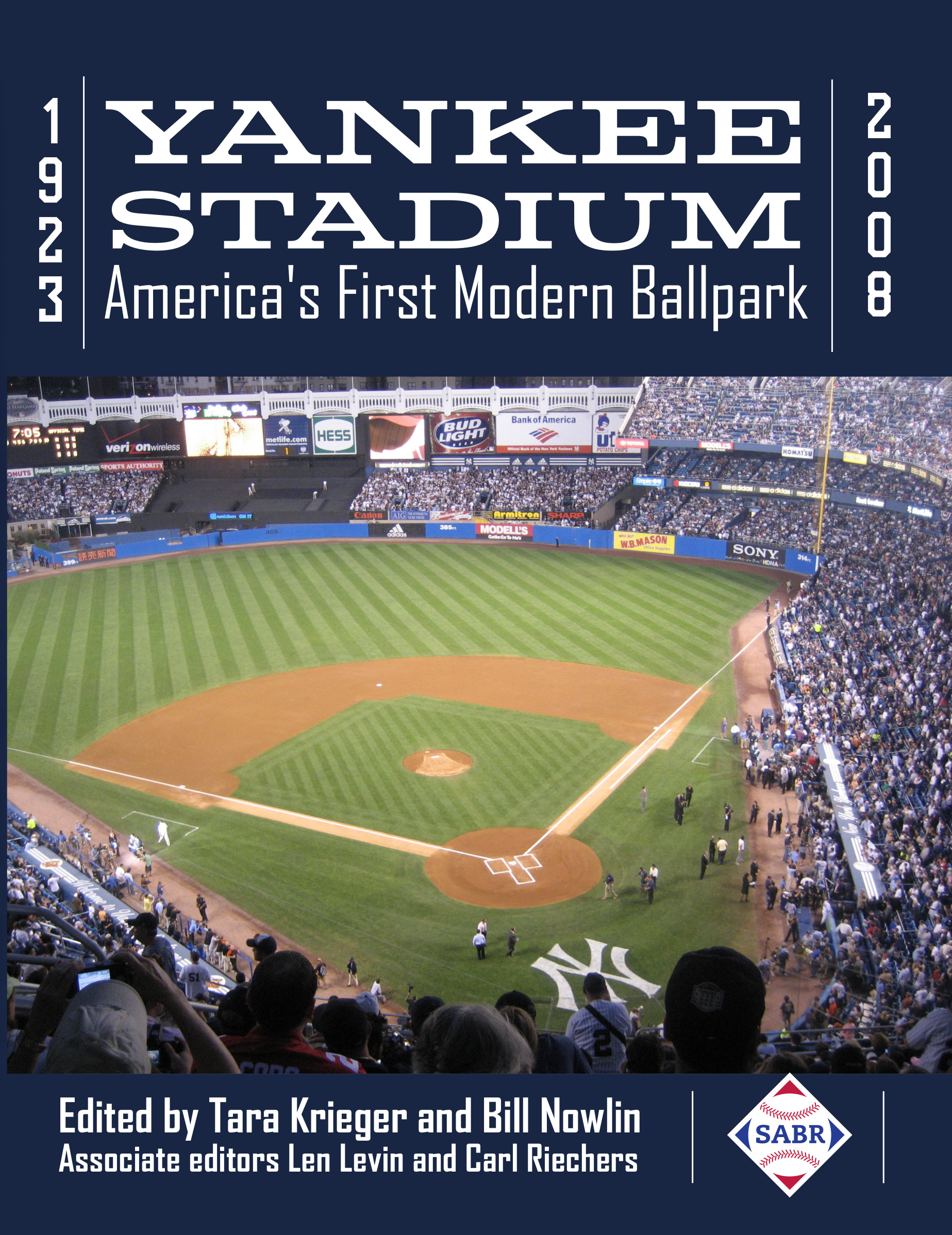

This article was published in Yankee Stadium 1923-2008: America’s First Modern Ballpark

The headline in the March 13, 1903, edition of the New York Times read “Baseball Grounds Fixed.” The nonbylined article described an agreement, announced by American League President Ban Johnson, that a plot of rocky land was leased for the construction of a ballpark to be occupied by the newly minted New York American League Baseball Club. It was in an elevated section of upper Manhattan, at 168th Street and 11th Avenue, with a spectacular view of the Hudson River and the New Jersey Palisades when looking west. On it, Hilltop Park was built, becoming the home to the American League Baseball Club of New York, nicknamed the Highlanders (soon to be renamed the Yankees), for the next 10 years.

The headline in the March 13, 1903, edition of the New York Times read “Baseball Grounds Fixed.” The nonbylined article described an agreement, announced by American League President Ban Johnson, that a plot of rocky land was leased for the construction of a ballpark to be occupied by the newly minted New York American League Baseball Club. It was in an elevated section of upper Manhattan, at 168th Street and 11th Avenue, with a spectacular view of the Hudson River and the New Jersey Palisades when looking west. On it, Hilltop Park was built, becoming the home to the American League Baseball Club of New York, nicknamed the Highlanders (soon to be renamed the Yankees), for the next 10 years.

In this same article, Ban Johnson described how “legal issues” always seemed to rise as individuals with a vested interest against the establishment of a new club in New York somehow managed to convince the city to cut a street through the middle of a desired American League property. It was a veiled reference to the National League’s New York Giants and their owners, primarily the former owner Andrew Freedman, whose Tammany Hall connections often enabled them to successfully block the progress of the Americans.1 The negotiations for the hilltop were completed in secrecy and a successful lease arrangement was made, but, according to Johnson, an ace-in-the-hole always had to be at the ready, in case the agreement fell through at the last minute. Johnson described his contingency plan as such:

“Had there been a slip up on this property, we had everything shaped to the minute to sign a lease for the Astor estate at One Hundred and Sixty-first Street and Jerome Avenue (in the Bronx), in which event the American League would have conducted the club.”2

In an irony of all ironies, this location in the Bronx was destined to become baseball’s most famous address in 1923 as the site of the original Yankee Stadium.

As early as autumn 1902, before the Highlanders ever played a game, the Bronx was being mentioned as a possible home for the new club.3 Proponents felt it was a fertile ground with an untapped fan base for baseball. However, the new interborough elevated and underground rail systems to the Bronx were still in the planning stages, raising a concern about the ability of Manhattan fans to reach the Bronx easily.

Highlanders owners Frank Farrell and Bill Devery were partial to a Manhattan location, but events quickly conspired to make Hilltop Park obsolete. First, before the beginning of the 1911 season, the wooden Polo Grounds in upper Manhattan burned to the ground, leaving the Giants without a home. In a grand gesture, Farrell offered the use of Hilltop Park to the Giants while the new concrete-and-steel Polo Grounds was being built. Concurrently, the Yankees’ 10-year lease on the Hilltop Park property expired after the 1912 season, not to be renewed. Before his death, Giants owner John T. Brush offered the use of the new Polo Grounds to Farrell, returning the favor of the year before. It provided the Yankees a temporary home in Manhattan, but the Bronx still beckoned.

In 1911 Farrell turned his attention to a plot of land in the Kingsbridge section of the Bronx, at 221st Street and Broadway, for a new park for the Yankees. The site was just north of where the Harlem River bends and becomes the Spuyten Duyvill Creek. Farrell had plans for a 32,000-seat concrete-and-steel stadium, whose entrance on Broadway would be a short walking distance from the 225th Street subway station. He announced his plans with great fanfare, yet some problems still had to be resolved. Legal issues involving the existing owners of the property arose regarding the future transfer of ownership of the grounds. Additionally, the proximity to the river rendered the plot of land a swamp, causing Farrell to arrange for the digging of drainage tunnels and the grading of the land by importing considerable rock and gravel from the excavation site for Grand Central Terminal in Manhattan.4 The dual legal and excavation expenses would be a blow from which Farrell’s ownership would not survive, and by the end of the 1914 season, the Yankees were up for sale, still without a new ballpark of their own.

A Manhattan brewery magnate, Colonel Jacob Ruppert Jr., along with Captain T.L. Huston, expressed interest in the club, but a review of the Yankees’ finances almost derailed the deal. In a 1931 article, Ruppert said, “I never saw such a mixed-up business in my life – liabilities, contracts, notes, obligations of all sorts. We went through it thoroughly, my lawyer and I. There were times when it looked so bad no sane man would put a penny into it.”5 A deal was struck, however, and it was immediately revealed that Ruppert and Huston had plans for a new ballpark … again, in the Bronx! The rumor had ground being prepared for a new stadium on Astor property along Westchester Avenue and Clason Point Road, east of the Bronx River.6 This, too, was not to be. The next rumor had Ruppert interested in land in Long Island City, Queens, at the foot of the 59th Street Bridge,7 as well as other sites in Manhattan. Ruppert then decided to focus on a long-term lease at the Polo Grounds,8 as the gathering storm clouds of World War I served as a deterrent to any firm investment plans.

After the war’s end, Ruppert set out in earnest to build his ballclub. In late 1919 he acquired pitcher Carl Mays from the Boston Red Sox. Mays was having disagreements with the Red Sox management, yet the purchase of Mays was viewed as “a serious breach of something or other,” according to Ruppert. Ban Johnson suspended Mays, and Ruppert applied for a court injunction, which was allowed.9 Johnson, who rarely had an associate with whom he didn’t feud, turned his animosity toward Ruppert by plotting to revoke the club’s charter if it did not have a stadium to play in. Johnson proceeded to pressure Charles Stoneham and John McGraw to evict the Yankees from the Polo Grounds, which the Giants were more amenable to do at this point. The Giants outdrew the Yankees by approximately 90,000 in 1919. In December the Yankees had purchased Babe Ruth and by mid-May they were outdrawing their landlords considerably, much to the Giants’ chagrin. On May 14, 1920, Giants treasurer Francis X. McQuade announced that the Yankees would no longer be welcomed at the Polo Grounds after the 1920 season.10

This drew an immediate and well-planned response from Ruppert. Knowing that his team needed a place to play, Ruppert informed Johnson that he owned a parcel of land at Madison Avenue and 102nd Street, a single city block, much too small to accommodate a major-league ball field. Ruppert promised to build a small grandstand and field, playing games at a park where every fly ball would result in a home run, causing great embarrassment to Johnson. Johnson backtracked, intervened with the Giants ownership, and the eviction was called off.11

Ruppert later revealed that this situation, as well as the enormous popularity of the aforementioned Babe Ruth, convinced him that it was time to no longer be “a tenant ballclub.” Although he said that he and the Giants’ Charles Stoneham had a good relationship and there was no danger of any further eviction action,12 Ruppert decided it was his time to build a triple-decked mega-structure to house not only the Bambino, but also the new legion of fans who followed Ruth and the suddenly competitive Yankees. The long-standing view of the Giants evicting the Yankees because of Babe Ruth’s popularity, while perhaps plausible, was not the main reason for Ruppert’s decision to leave the Polo Grounds and build his own ballpark. It was primarily a shrewd business move on the part of Ruppert, one of many successful decisions he made during his ownership. He had a hot product, and he sought to capitalize on it.

Ruppert’s choice of land was that Astor property originally mentioned by Johnson as his fallback position in case the Hilltop Park deal fell through in 1903 – 161st Street and Jerome Avenue in the Bronx on the east bank of the Harlem River, directly opposite the Polo Grounds. The Bronx beckoning came full circle. What Ruppert built was an edifice described by writer F.C. Lane in the April 29, 1923, issue of Baseball Magazine the following way: “From the plain of the Harlem River it looms up like the great pyramid of Cheops from the sands of Egypt.”13 Or, less dramatically but far more popular, it was “The House That Ruth Built,” the original version of which endured for the next 50 years. Yankee Stadium was not referred to in that way until Opening Day, April 18, 1923, when New York Evening Telegram writer Fred Lieb surveyed the scene after the Babe’s dramatic home run into the right-field stands. Lieb considered both the Ruth-friendly dimensions in right field, as well as the Babe’s already proven ability to put people into the seats, and christened the ballpark as “The House That Ruth Built” in his game column.14 Yet, according to Ruth, it was that Opening Day home run that gave Lieb’s phrase its staying power.15 Claire Ruth, Babe’s wife, was quoted as saying, “I think that was the proudest moment of his life, and I think he believed that it would never have been ‘The House That Ruth Built’ if he hadn’t hit that home run that day.”16

After the City of New York renovated the original Yankee Stadium in 1974-75, many continued to refer to the new building as “The House That Ruth Built.” Though it wasn’t the same exact stadium, it was on the same footprint in the Bronx, the land that had beckoned since 1903. New challenges to the Bronx would emerge in the late 1980s when George Steinbrenner had serious discussions with the New Jersey Sports and Exposition Authority about moving the Yankees to the Meadowlands Sports Complex, adjacent to Giants Stadium.17 The Bronx eventually won this challenge, too, and the new Yankee Stadium, which opened in 2009, sits directly across East 161st Street from the original site. The Yankees are synonymous with the Bronx, and will remain so for the distant future.

BOB GOLON is a retired manuscript librarian and archivist at Princeton Theological Seminary library. He also spent three years as labor archivist at Rutgers University Special Collections and University Archives. Bob is past president of the New Jersey Library Association History and Preservation section and a member of the Mid-Atlantic Regional Archives Conference. Prior to getting his MLIS from Rutgers University in 2004, Bob worked 18 years in sales and marketing for the Hewlett-Packard Company, working with the group that established the successful dealer distribution channel for HP printers and personal computers. A baseball historian and SABR member, Bob has been a contributor to various publications, can be seen prominently on the YES Network’s Yankeeography – Casey Stengel, and is the author of No Minor Accomplishment: The Revival of New Jersey Professional Baseball (Rivergate Books/Rutgers University Press, 2008).

NOTES

1 Ray Robinson and Christopher Jennison, Yankee Stadium: 75 Years of Drama, Glamor, and Glory (New York: Penguin Group, 1998), 2.

2 “Baseball Grounds Fixed,” New York Times, March 13, 1903.

3 “American League Here,” New York Times, September 7, 1902.

4 “Farrell’s New Ball Park,” New York Times, November 12, 1911.

5 Jacob Ruppert, “The Ten-Million-Dollar Toy,” Saturday Evening Post, March 28, 1931.

6 “Yankees in the Bronx,” New York Times, May 13, 1915.

7 “Yanks New Home Will Be in Queens,” New York Times, October 3, 1915.

8 “Yankees Seek Lease,” New York Times, December 14, 1915.

9 Ruppert, “The Ten-Million Dollar Toy.”

10 “Yanks Lose Home at Polo Grounds,” New York Times, May 15, 1920.

11 Steve Treder, Forty Years a Giant: The Life of Horace Stoneham (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2021), 28-29.

12 Ruppert, “The Ten-Million-Dollar Toy.”

13 Robinson and Jennison, Yankee Stadium: 75 Years of Drama, Glamor, and Glory, 2.

14 Robert Weintraub, The House That Ruth Built: A New Stadium, the First Yankees Championship, and the Redemption of 1923 (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2011), 22.

15 “The House That Ruth Built,” www.baberuthcentral.com/babesimpact/babe-ruths-legacy/the-house-that-ruth-built/, accessed August 22, 2022.

16 “The House That Ruth Built.”

17 Bob Golon, No Minor Accomplishment: The Revival of New Jersey Professional Baseball (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press/Rivergate Books, 2008), 41.