Grunts, Groans And Theater: Wrestling at Yankee Stadium

This article was written by Luis A. Blandón Jr.

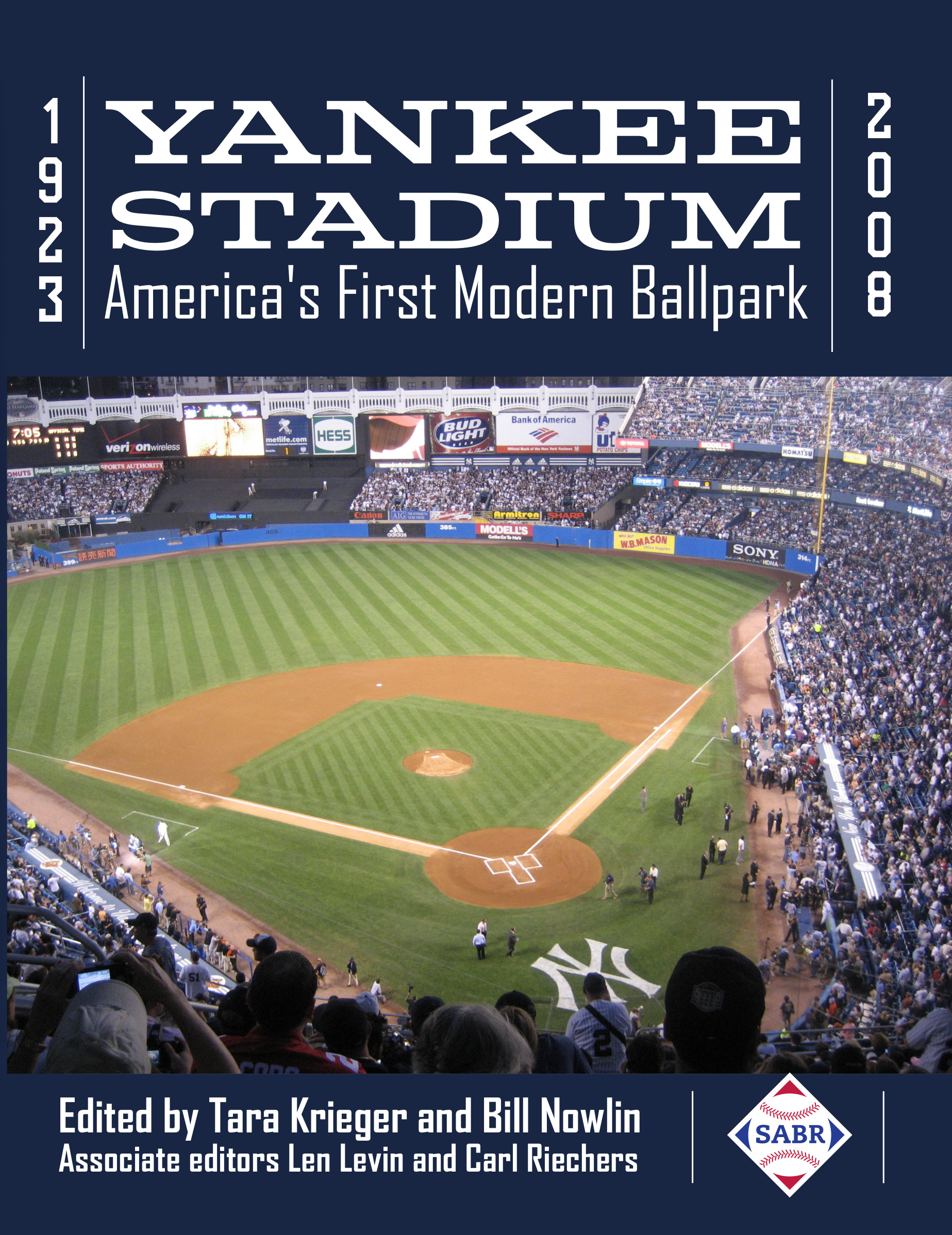

This article was published in Yankee Stadium 1923-2008: America’s First Modern Ballpark

Sir Ray Davies of The Kinks wrote and sang in Over the Edge: “Everybody is a victim of society, Comedy, tragedy, vaudeville, variety, Pantomime players in the grand tradition, Forced into roles that leave them totally driven.”1 The melodic lyric unknowingly described the phenomenon of professional wrestling in the United States.

Sir Ray Davies of The Kinks wrote and sang in Over the Edge: “Everybody is a victim of society, Comedy, tragedy, vaudeville, variety, Pantomime players in the grand tradition, Forced into roles that leave them totally driven.”1 The melodic lyric unknowingly described the phenomenon of professional wrestling in the United States.

On the amateur level, wrestling is a sport. On the professional level, it is vaudeville theater. The ring is the stage. The wrestlers are the pantomime. The audience are active participants. It is elaborate and bombastic with thrills and comedy. This is the heartbeat of pro wrestling. A fight for glory, realistic violence, and manufactured championships. It tells a story. It is an escape from reality.

In the first half of the twentieth century, wrestling’s popularity in the United States was just below that of baseball, horse racing, and boxing. In New York City, matches were held at each iteration of Madison Square Garden, the Seventy-First Regiment Armory, Bronx Coliseum, St. Nicholas Rink, the Broadway Arena, the Coney Island Velodrome, Queensboro Stadium, and sometimes, perhaps reluctantly in a handful of instances, Yankee Stadium in the Bronx.

The original Yankee Stadium evolved into baseball’s hallowed grounds from the moment it opened in 1923. Iconically known as “The House That Ruth Built” and as the birthplace of Yankees’ winning history, “The Cathedral of Baseball” hosted an abundance of sporting and nonsporting events during its existence on East 161st Street and River Avenue in the Bronx.

Professional wrestling has a hold on a segment of the American sports-watching population and the heartbeat of the sport has been in New York City with Madison Square Garden serving as its mecca. Since 1879, professional wrestling has been on the Garden’s calendar, evolving into a profitable attraction for the promoters and for the arena’s owners. Though the Garden was anointed “wrestling’s holy grounds,” the five boroughs of New York had several venues where wrestling matches were held.2 Syndicates or cartels controlled professional wrestling by territory, dictating who won or lost, who was a champion, and who was a good or bad guy. Battle plans and strategy were prepared and acted out and championship bouts were critical to the sport and for the profits for all involved. It was an act, as noted by the New York Times in 1934: “The wrestling fans of New York and vicinity are accustomed to airplane spins, grind and lofty tumbling, butting, gouging and common assault and battery in the good-natured guise of wrestling, all in a spirit of fun.”3

When Yankee Stadium open its doors in 1923, it was apparent that it would compete with the Polo Grounds for non-baseball events. It was expected that “there probably will be frequent boxing bouts and wrestling bouts” at Yankee Stadium.4 Instead, wrestling evolved as a minor bit player.

Wrestling matches were performed in Yankee Stadium in 1931, 1933, and 1935. From 1936 until 1950, no matches were held there. The following are stories of four cards, the charity that benefited from the matches, and the story of an Italian heavyweight boxer, nicknamed the Ambling Alp, who boxed and wrestled on the hallowed infield.

CARD #1: THE FREE MILK FUND FOR BABIES

Millicent Hearst was the wife of publisher William Randolph Hearst. Married on April 28, 1905, and having raised five sons, they separated in 1933.5 An active philanthropist in New York focused on poverty and children, Millicent Hearst founded the Free Milk Fund for Babies, Inc. in 1921.6 The fund provided daily milk to children of families in need. For decades, the Free Milk Fund was the beneficiary of donations from charitable contributions collected from the percentage of tickets sold at events throughout the city such as movie premieres, Broadway openings, Metropolitan Opera festivities, fashion shows, and boxing and wrestling matches.7 By 1950, the Fund had distributed “9,252,453 quarts of milk free.”8

The Free Milk Fund shared in the proceeds of the wrestling cards held at Yankee Stadium. One of these first occurred in a 10-match card on June 29, 1931. Promoter Jack Curley expected “the event to surpass anything ever attempted in wrestling.”9 With Mayor Jimmy Walker in attendance, “a throng of 30,000” arrived to see the festivities.10 The card featured the Golden Greek, Jim Londos, retaining his heavyweight title “in a grueling struggle” that kept the crowd “on edge for the entire duration of the thrilling match,” pinning Ray Steele in a double armlock and half-nelson in 1:09:34.11 “Standing groggily with his hand on the top strand of the ring rope,” Londos took in the adulation of the fans.12 With receipts totaling $63,000 ($1,238,338.01 in 2022 dollars), the Free Milk Fund “profited handsomely from the battle.”13 The 11:00 P.M. curfew was extended by the head of the New York State Athletic Commissioner, Brigadier General John J. Phelan, so the championship match could be held.

CARD #2: A SOGGY MESS

On June 12, 1933, the Free Milk Fund shared in the profits from the eight-match card that featured Jim Browning keeping his heavyweight title, defeating Jumping Jack Savoldi, the former Notre Dame gridiron star. The event drew 6,000 spectators who braved a wet, dreary evening with rain a constant presence. When the wrestlers were introduced, “rain descended and the few spectators who occupied ringside seats rushed for the grandstand.”14 The two men “pulled, tugged and battered each other until 11 o’clock[,]” when the curfew halted the grappling.15 The match was awarded to Browning by decision in 1:18:05. The afternoon rains quelled the expected high attendance and gate.

CARD #3: CHAMP DEFENDS TITLE

In the 1930s, wrestling was controlled by the “Trust.” It was a cartel or syndicate of promoters who determined what happened in wrestling, whom to put their financial resources behind, and who would be the champion. The Trust determined in 1935 that Irishman Danno O’Mahony was to be the champion instead of Jim Londos.16 According to wrestling historian Tim Hornaker, Londos received $50,000 ($1,040,036 in 2022 dollars) for losing the title to O’Mahony on June 27, 1935 in Boston.17

The July 8, 1935, six-match wrestling card was the last one held at Yankee Stadium until 1950. Jack Curley predicted a crowd of 20,000 and a profitable gate because “interest in the bout was widespread.”18 The featured match was heavyweight title match between O’Mahony and Chief Little Wolf of Trinidad, Colorado (his real name was Ventura Tenario).

The year 1935 saw O’Mahony as “arguably the most famous Irish sports star in the world.”19 His rise was rapid from a private in the Irish Free State Army at the end of 1934 to coming to United States on a leave of absence and being encouraged to wrestle by his manager, Jack McGrath. O’Mahony was known for the “Irish Whip,” which saw him lift his opponent over his shoulder and throwing him onto the mat. Wolf used his “Indian Death Lock,” a leg hold, to defeat his foes. In press accounts of the era, racism and stereotypes were in the forefront. The New York Daily News said “[L]ogic dictates that Danno will down the Chief because con-census [sic] figures show that there are more brogues than war-whoops in our fair city.”20 The ring was built upon home plate. A crowd of 40,000 was expected. The Milk Fund “will slice 10 per cent. of the gate receipts.”21

Little Wolf was born in Hoehne, Colorado, second of four children of Porfirio (Joseph) Tenario, “half Navajo-half Spanish,” and his wife, Maria Soleila “Mary” Tenario, “a full-blooded Navajo Indian.”22 He was known for his compassion for children, performing Navajo dances in children’s hospitals. With his success in the ring, Wolf acquired “a 500-acre ranch near Trinidad, Colorado, where he raised cattle and horses and grew sugar beets.”23 He later became a wrestling icon in Australia.

Far from the promised near-sellout, 12,000 spectators walked through the turnstiles to see O’Mahony’s first title defense. The wrestlers were introduced in costumes befitting a vaudeville-era production. O’Mahony was clad in a green dressing gown alluding to a golfer that “made you ache for a putter and ball.”24 Wolf wore a blanket adorned with images of Native Americans and culture that “looked as if someone had taken a snapshot of the inside of an Indian trading post.”25 Likely part of the script, before the match Wolf primped and bellowed in the ring, “Whooooooo” at the seated patrons.26 Wolf dominated the match until the act’s climax, when O’Mahony pinned him to the mat after several forearms to Wolf’s face that bloodied his nose. Defending his “title,” O’Mahony won the match via a pinfall, after 28 minutes and 23 seconds.27

Both men had tragic outcomes later in life. In 1958 in Melbourne, Australia, Chief Little Wolf suffered a series of devastating strokes “that badly affected one side of his body and face” and left him wheelchair-bound for the rest of his life.28 Highly respected in Australia, he lived at the Mount Royal Special Hospital for the Aged from 1961 to 1980, then returned to the United States, where he died on November 13, 1984, in Seattle.

After his tenure as champion was deemed to end, O’Mahony wrestled in the United States through 1948. He was considered a popular ethnic draw for promoters. He served in the US Army during World War II and was later employed as a publican in Santa Monica, California.29 He returned home to Ireland in 1950. On November 3, 1950, O’Mahony suffered fatal injuries in a crash involving his parked truck in Port Laighaise.30 He was 38. A bronze statue of O’Mahony welcomes all to his home village of Ballydehob.31

“THE AMBLING ALP”

About two weeks earlier, on June 25, 1935, at Yankee Stadium, the 21-year boxer Joe Louis, known as the Brown Bomber, knocked out a slow ex-heavyweight champion of the world, the 6-foot-5.75-inch, 265-pound Primo Carnera, known as the Ambling Alp, in the sixth round of a scheduled 15-round bout.32 The Free Milk Fund shared in the gate profits of $375,000 ($8,124,306.57 in 2022 dollars). Carnera returned to fight at Yankee Stadium 15 years later, this time as a professional wrestler.

From Sequals in northern Italy, Carnera was previously a circus strongman who became a mediocre boxer rumored to be under the influence of the mob. He later became an actor and wrestler.33 Budd Schulberg’s novel The Harder They Fall has been called a thinly disguised portrayal of Carnera’s life.34 After the Louis loss, Carnera fought sporadically.35

Carnera lived with his family in Sequals during World War II and was used as a reluctant propaganda tool by Benito Mussolini. In 1941 during the British North African campaign against Italy, Mussolini dictated that a boxing match occur between Carnera and a captured hulking black South African Army POW, Kay Masaki, to demonstrate the superiority of the White race over Blacks in a propaganda film. Carnera was “the victim of the most ignominious defeat in his ponderous career.”36 Though he had never boxed and after being knocked to the canvas by Carnera at the start of the fight, Masaki was not the easy foil for the Italians, knocking Carnera out in the first round by delivering “a fearful haymaker under the Italian’s jaw. Carnera fell in a heap. The cameras ceased grinding.”37 At the war’s conclusion, broke and needing to take care of his family, he turned to professional wrestling as an avenue to make money. He became a popular attraction and a financial success at the box office in the American grunt-and-groan world into the 1960s. Carnera is the only man in history to be both boxing’s world heavyweight champion and professional wrestling’s world champion.38 Carnera was one of a handful who both wrestled and boxed at Yankee Stadium.

CARD #4: WRESTLING RETURNS

Like few events in human history, television changed the way Americans existed. TV and wrestling were natural partners. In 1949 wrestling aired three times a week on New York City television. And there was a demand for more. Promoter Billy Johnson pushed to have a wrestling show at Yankee Stadium, negotiating an event for the summer of 1950. He envisioned a gate of more than $250,000 with a top ticket price of $5. ($3,078,921.16 and $61.58 in 2022 dollars). He dreamed of a future $1 million gate at the Stadium ($12,315,684.65 in 2022 dollars).39

The match between Antonino Rocca and Don Eagle, postponed to July 12 due to rain, received poor reviews for its length and lack of an interesting story line. (Public domain)

After an absence of 15 years, “grapplers performed in the House that Ruth Built” in an all-star wrestling card on Wednesday, July 12, 1950.40 Postponed from July 10 due to rain, the eight bouts featured Italian-born Argentine Antonino Rocca vs. 23-year-old Canadian Mohawk Indian Don Eagle “in a finish combat.”41 Rocca was the top attraction in professional wrestling, “who been driving wrestling fans wild on television.”42 Known as Mr. Perpetual Motion and wrestling with his trademark bare feet, Rocca was a popular icon for Italians and Latinos in New York City and other major Eastern cities.

“The main event was the dullest, aside from being the longest,” observed the New York Times.43 Rocca and Eagle demonstrated little comedy, a poor storyline, no suspense, and no thrills. In the undercard matches, “the crowd was treated to an overabundance of [comedy and slugging] … when laughs were the proverbial dime a dozen.”44 As Rocca and Eagle tugged and groaned attempting dropkicks, holds and slaps, the state’s “11 o’clock curfew dictated a halt” with both men still standing at the end.45 The match ended in a draw after 55 minutes and 5 seconds.46

Carnera was featured in a preliminary match against Emil Duskek of Omaha, Nebraska. Carnera had been on the road traveling from “New York to Caracas Venezuela, and back then to Nome, Alaska, in pursuit of bucks, pesos, etc.”47 Past his glory years, Carnera was said to have been making “a comfortable living in this sport.”48 He pinned Dusek in a “hold described as a leg grapevine and body press” at the 15:27 mark for a victory.49 To the eyes of the paying fans, other than Rocca and perhaps Eagle, “the wrestlers were overaged, overfed and, as a result, decidedly overweight.”50 Nonetheless, “[I]t was fun … and no one complained.”51

Local and national press accounts considered that the matches were not up to expected standards. But for the Free Milk Fund, “there were 11,328 men and women who could find no humor in an infant’s need for milk and a portion of $33,746.90 ($415,616.18 in 2022 dollars) they paid to watch the show will go to the fund.”52

The hyped financial windfall and huge crowd never manifested. The poor turnout, hindered by the postponement, was challenged by the middleweight boxing championship bout between champion Jake LaMotta and Italian contender Tiberio Mitri at Madison Square Garden. LaMotta “laughed off the first defense hoodoo last night to conquer the previously unbeaten” Mitri in a unanimous decision.53 With 16,369 providing receipts of $99,841 ($1,229,610.27 in 2022 dollars), boxing at a smaller venue outperformed wrestling in New York City that evening.

Carnera became a US citizen in 1953. His life in wrestling was better than the life he experienced as a boxer. Carnera wrestled into the early 1960s. He found a third chapter in his life as an actor in bit roles in Hollywood.54 A heavy drinker and his health weakened by diabetes and liver cirrhosis, he died at the age of 60 in his home village of Sequals, on June 28, 1967.

WRESTLING TODAY

Wrestling never became an enduring attraction at the original Yankee Stadium. The new Yankee Stadium is not even a minor player in professional wrestling in New York City. Instead, World Wrestling Entertainment hosts events at the Madison Square Garden, Barclay Center, the Meadowlands Sports Complex, and Prudential Center, among others.

Wrestling is now a billion-dollar industry with productions held in major cities and available to all by pay per view, streaming, or cable television. Gimmick or concept matches have spawned well-known actors and celebrities. It is still an act with good and evil characters and a show now with a wider reach. But as it was nearly 100 years ago, it is still just theater.

LUIS A. BLANDON JR., a Washington, DC native, is a producer, writer, and researcher in video and documentary film production and in archival, manuscript, historical, film, and image research. His creative storytelling has garnered numerous awards, including three regional Emmys, regional and national Edward R. Murrow Awards, two TELLY awards, and a New York Festival World Medal. He worked as a producer and/or researcher on several documentaries including Jeremiah; Feast Your Ears: The Story of WHFS 102.3; and #GeorgeWashington. Most recently he was co-producer of the documentary The Lost Battalion. He is serving as a consultant on a documentary film project for the United States Naval Academy’s Stockdale Center for Ethical Leadership and Maryland Public Television on the Vietnam War POWs and leadership. He was senior researcher and manager of the story development team for two national programs for Retirement Living Television. He has worked as a historian for two public-policy research firms: Morgan Angel & Associates and MLL Consulting LLC. He served as the principal researcher for several authors including for The League of Wives by Heath Hardage Lee and her current biography project on First Lady Pat Nixon. He has a master of arts in international affairs from George Washington University.

NOTES

1 Raymond Douglas Davis, “Over the Edge,” performed and recorded by The Kinks, produced by Raymond Douglas Davies, Phobia (compact disc), Columbia Records, 1993: Track 9.

2 Jamie Greer, “Wrestling Meccas: Madison Square Garden, New York City,” Last Word on Pro Wrestling, May 27, 2020. https://lastwordonsports.com/prowrestling/2020/05/27/wrestling-meccas-madison-square-garden-new-york-city, accessed September 20, 2022. The phrase “wrestling’s holy grounds” has historically been used to describe the impact Madison Square Garden had on the growth and popularity of professional wrestling in the United States. See: Graham Cawthorn, Holy Ground: 50 Years of WWE at Madison Square Garden (The History of Professional Wrestling) (Scotts Valley, California: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2014) and Kevin Sullivan, “Madison Square Garden Really is the Mecca of Wrestling Arenas,” yesnetwork.com, July 12, 2014. See https://web.archive.org/web/20181215065850/http://web.yesnetwork.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20150602&content_id=128106928&fext=.jsp&vkey=news_milb, accessed November 30, 2022.

3 John Kieran, “Sports of the Times: Wrestling, Southern Style,” New York Times, March 27, 1934: 26.

4 W.O. McGeehan, “Boxing at Polo Grounds Opens Promoters’ Battle,” New York Herald, August 4, 1923: 10.

5 Millicent Hearst survived her separated husband, who died on August 14, 1951. She died on December 5, 1974.

6 “Millicent Hearst (1882-1974),” Hearst Castle, https://hearstcastle.org/history-behind-hearst-castle/historic-people/profiles/millicent-hearst/. When the Free Milk Fund was founded, federal government antipoverty and nutrition programs were not available for those in need of such assistance.

7 For example, the Fund was the targeted charity designated by a special performance at the Metropolitan Opera of Strauss’s Salome and Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi, on January 10, 1952. See “‘Met’ to Aid Free Milk Fund,” New York Times, December 6, 1951: 42. For more, see “Exhibition: A Pictorial Review, Greater New York’s Silver Jubilee, May 26-June 23, 1923, William Randolph Hearst Archive, http://www.liucedarswampcollection.org/betahearst/education.php, accessed August 16, 2022.

8 “Opera on Friday to Aid Milk Fund,” New York Times, January 31, 1950: 17.

9 “Londos and Steele Wrestle Tomorrow,” New York Times, June 28, 1931: S11.

10 Arthur J. Daley, “30,000 See Londos Retain Mat Crown,” New York Times, June 30, 1931: 28.

11 Daley.

12 Daley.

13 Daley. In several instances, the conversion rates are taken from CPI Inflation Calculator, US Bureau of Labor Statistics. At https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm.

14 Joseph C. Nichols, “Browning Retains World’s Title,” New York Times, June 13, 1933: 24.

15 Nichols.

16 The American press frequently misspelled his name as “O’Mahoney.”

17 Tim Hornaker, “New York City Wrestling Today,” www.legacyofwrestling.com. On June 27, 1935, at Boston’s Fenway Park, O’Mahony “defeated” Londos to win the New York State Athletic Commission World Heavyweight Championship, which was also recognized by the National Wrestling Association.

18 Joseph C. Nichols, “O’Mahoney to Risk Heavyweight Mat Title Against Little Wolf at Stadium Tonight,” New York Times, July 8, 1935: 19.

19 Joe O’Shea, “Danno – Champion of the World,” Southern Star (West Cork, Ireland), November 8, 2016. See https://www.southernstar.ie/sport/danno-champion-of-the-world-4129576, accessed October 12, 2022.

20 Kevin Jones, “Danno Rassles Chief in 1st Title Defense,” New York Daily News, July 7, 1935: 70.

21 Kevin Jones, “Danno vs. Chief Is Expected to Draw 40,000,” New York Daily News, July 8,1935: 8.

22 Barry York, “Tenario, Ventura (Chief Little Wolf) (1911-1984),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/tenario-ventura-chief-little-wolf-15813/text27012, published in 2012, accessed online October 7, 2022.

23 York.

24 Henry McLemore, United Press, “‘Strictly Dishonorable’ Is Mac’s Title for Mat Face,” The Times (Munster, Indiana), July 9, 1935: 24.

25 McLemore.

26 Kevin Jones, “O’Mahoney Pins Indian in 28:23,” New York Daily News, July 9, 1935: 47.

27 Joseph C. Nichols, “Crowd of 12,000 See O’Mahoney Retain Wrestling Championship at the Stadium,” New York Times, July 9, 1935: 26.

28 York, “Tenario, Ventura (Chief Little Wolf) (1911-1984).”

29 Jack McCarron, “Ballydehob’s Danno O’Mahony Was the ‘the First True Ethnic Super-Draw’ in Professional Wrestling,” Southern Star (West Cork, Ireland), April 7, 2020. https://www.southernstar.ie/sport/ballydehobs-danno-omahony-was-the-the-first-true-ethnic-super-draw-in-professional-wrestling-4203430, accessed October 10, 2022. O’Mahony managed a pub/bar.

30 “O’Mahoney Dies in Crash: Wrestled Here Many Times,” Washington Evening Star, November 4, 1950: A-10; Associated Press, “Danno O’Mahoney Dies,” New York Times, November 4, 1950: 20.

31 McCarron.

32 James P. Dawson, “Louis Knocks Out Carnera in Sixth; 60,000 See Fight,” New York Times, June 26, 1935: 1. Carnera was the world heavyweight boxing champion from June 29, 1933, to June 14, 1934. He won the championship by knocking out Jack Sharkey in the sixth round of the 15-round title match. He lost the title to Max Baer via a technical knockout in the 11th round of a scheduled 15-round title match.

33 Carnera had a small noncredited part in On The Waterfront (1954) that starred Marlon Brando.

34 The novel is the story of an Argentine peasant and circus performer, Toro Molina, who becomes a boxer managed by an unscrupulous fight promoter and his press agent. Molina cannot box. He is subsequently betrayed by all.

35 In 1938 the diabetic Carnera had a kidney removed, which forced him into semi-retirement. See Joseph S. Page, Primo Carnera: The Life and Career of the Heavyweight Boxing Champion (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2010), 179.

36 “Sport: Carnera v. Masaki,” Time, August 28, 1944, https://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,885648,00.html, accessed October 26, 2022.

37 “Sport: Carnera v. Masaki.”

38 For more on Carnera’s life and career as a boxer and wrestler, see Jack Sher, “The Strange Case of Carnera,” Sport, February 1948.

39 Lawton Carver, International News Service, “Mat Gate Is New Dream,” Stockton (California) Evening and Sunday Record, March 8, 1950: 45.

40 “11,328 See Wrestling Return to Stadium,” New York Times, July 13, 1950: 32.

41 “Wrestling at Yankee Stadium,” Morning Call (Paterson, New Jersey), June 27, 1950: 14.

42 “Rocca Breaks Crowd Mark,” Journal Herald (Dayton, Ohio), July 13, 1950: 9. Rocca’s birth name was Antonino Biasetton.

43 “11,328 See Wrestling Return to Stadium.”

44 “11,328 See Wrestling Return to Stadium.”

45 “11,328 See Wrestling Return to Stadium.”

46 “11,328 See Wrestling Return to Stadium.”

47 Hugh Fullerton, “Newcomers in All-Star Polls,” The Record (Hackensack,New Jersey), June 30, 1950: 18.

48 “11,328 See Wrestling Return to Stadium.”

49 “11,328 See Wrestling Return to Stadium”

50 “11,328 See Wrestling Return to Stadium.”

51 “11,328 See Wrestling Return to Stadium.”

52 “11,328 See Wrestling Return to Stadium.”

53 Associated Press, “LaMotta Trims Italian Easily,” Newsday (Suffolk Edition) (Melville, New York), July 13, 1950: 53.

54 For a list of credited Carnera acting roles, see https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0138712/.