100 Years Since Local Franchise’s First World Title: 1924 Washington Senators

This article was written by Stew Thornley

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Land of 10,000 Lakes (2024)

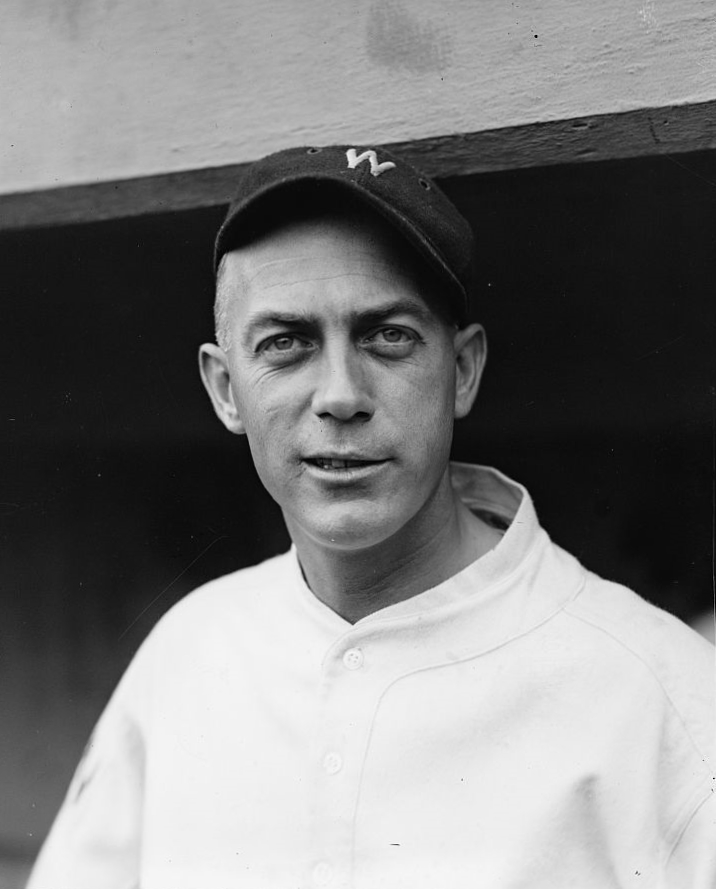

Lefty George Mogridge entered Game Seven of the 1924 World Series in relief for the Washington Senators, after starter Curly Ogden was pulled in the first inning. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Atop the right-field stands at Target Field in Minneapolis fly the pennants to celebrate league championships and world titles. The initial one is from 1924, the first World Series won by the franchise that spent 60 years in Washington and is now in its 64th season as the Minnesota Twins. Washington was a charter member when the American League took on major-league status in 1901. For most of its time in the capital, the team was officially the Nationals but often referred to as the Senators. Many of the years were moribund, spawning the crack, “Washington—First in war, first in peace, and last in the American League.”

However, the Senators had high points, and their top player, Walter Johnson, is often regarded as the greatest pitcher of all time. Johnson came to Washington in 1907 and was still a stalwart in the 1920s when the team finally won a pennant and went to the World Series against the New York Giants, who had won their fourth straight National League flag. The Giants’ manager was John McGraw, who was completing his 23rd season with the team. The Senators’ skipper was Bucky Harris, so young that he was known as the “Boy Manager.” Harris was 27 when he was given the job of manager to go with his duties at second base at the beginning of the 1924 season.

The World Series was shrouded in controversy on its eve. On October 1, Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis placed New York outfielder Jimmy O’Connell and coach Cozy Dolan on the ineligible list for trying to bribe Philadelphia Phillies shortstop Heinie Sand to “not bear down too hard” in a September 27 game between the Giants and Phillies. The Giants won that game 5–1, clinching the National League pennant. Sand reported the incident to his manager, who passed it on to league president John Heydler. Three other Giants—Frankie Frisch, Ross Youngs, and George Kelly—were implicated but cleared by the commissioner. Nevertheless, a cloud hung over the Giants for their attempt to get preferential treatment from another team during the pennant race.

Two days before the opening game, a rumor circulated that the Senators would not be playing the Giants, that New York had been disqualified and second-place Brooklyn would instead represent the National League in the World Series.1 But the series went on as planned, with the Giants meeting the Senators, though American League president Ban Johnson, who had demanded that the series be called off because of the scandal, refused to attend any of the games.

While the American League’s president was absent, the United States of America’s President, Calvin Coolidge, was on hand for the games in Washington and was as excited as any Senators fan. Many were even happier about the 36-year-old Johnson—who had hinted at retiring from baseball at the end of the season2—finally getting his chance. Senators fans were advised to not be “too vigorous” in shaking Johnson’s hand in order to protect his right arm.3

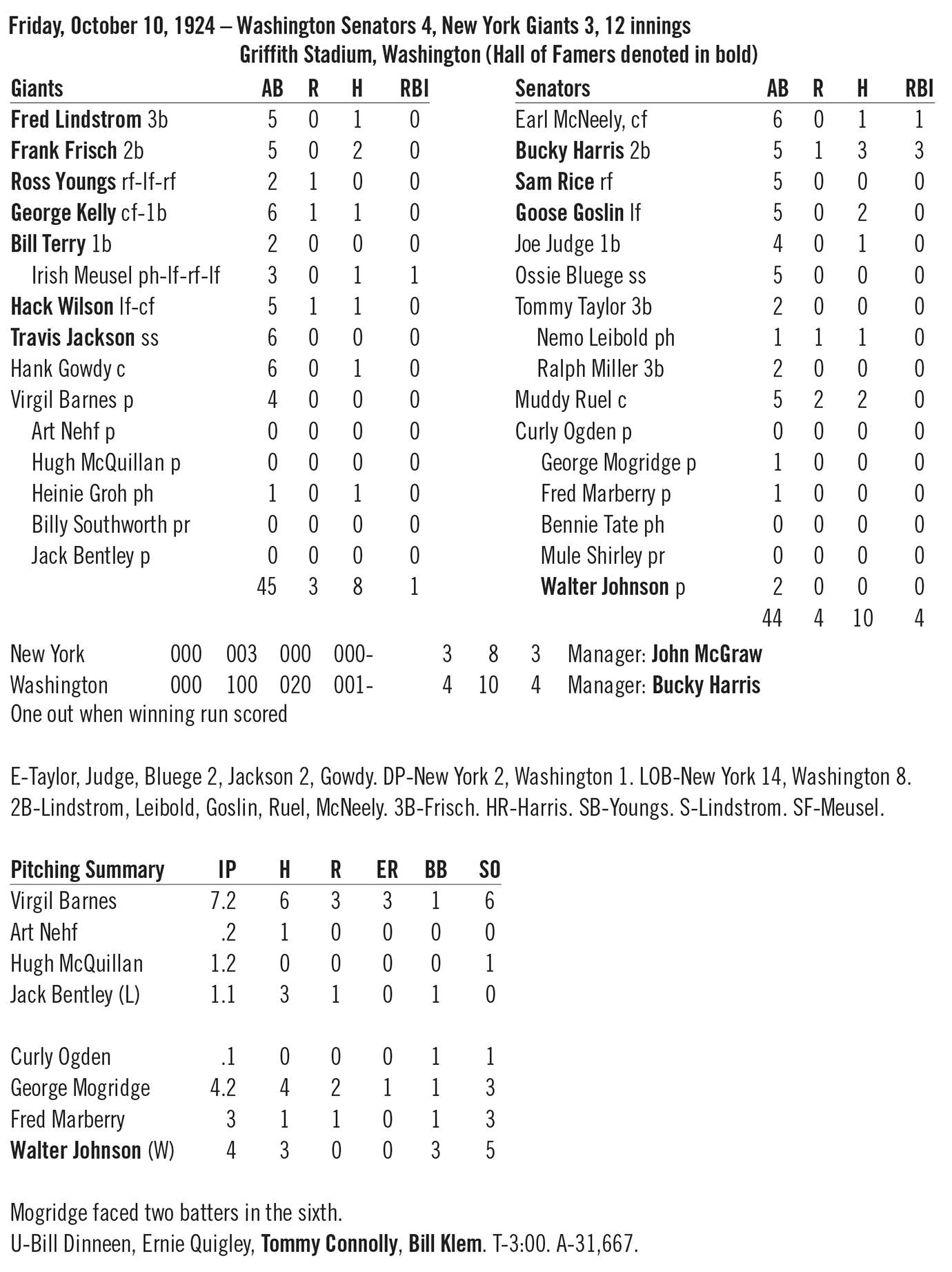

However, Johnson—who had won 23 games during the regular season—was the losing pitcher in the 12-inning opener as well as in the fifth game, and it looked like he wouldn’t get the World Series win that many were hoping for.

Clearly, Johnson would not start Game Seven.4 But it was unclear who would, as Harris wanted to keep McGraw guessing who would be in the starting lineup. In McGraw’s nine, the first seven spots in the batting order were occupied by players who are now in the Hall of Fame. However, he chose the lineup thinking Washington left-hander George Mogridge wouldn’t be the starting pitcher—which was exactly what Bucky Harris wanted.

Harris hoped that starting right-hander Curly Ogden, who had not pitched in the series, would cause McGraw to put left-handed-hitting Bill Terry in the starting lineup. Harris would then switch to a left-hander with the intention of prompting McGraw to pinch-hit for Terry, who would then be unavailable if Harris should come back with a right-hander.

The strategy worked—sort of. McGraw bit by starting Terry, but he did not replace him immediately after Harris made his switch. Harris even stuck with his ersatz starter longer than he had intended, after Ogden struck out Fred Lindstrom on three pitches to start the game. It was here that Harris had planned to call for Mogridge, and Ogden even started walking off the mound. However, his manager sent him back and told him to try another batter. This one—Frisch—walked, getting Harris to finally signal for Mogridge, the man he had wanted all along. Mogridge retired Youngs and Kelly to end the inning and kept the Giants off the scoreboard for the next four innings.

New York starter Virgil Barnes did even better in the early innings, keeping the Senators off the bases. Barnes retired the first 10 batters, five on strikeouts, when Bucky Harris hit a long fly that just cleared the low wooden fence in left field for a home run. Even laconic Cal Coolidge rose and joined in the prolonged applause.

The Washington lead held into the sixth when Mogridge started the inning by walking Youngs, who went to third on a single to center by Kelly. Terry was up next, and at this point McGraw finally made his move by sending Emil “Irish” Meusel up to hit for him. Harris countered by calling for right-hander Fred Marberry.

Meusel hit Marberry’s first pitch deep enough to right to bring in Youngs with the tying run. Hack Wilson sent Kelly to third with another single to center. Travis Jackson then rolled a soft grounder to first that Joe Judge bobbled. Kelly, after initially holding, raced home as Jackson reached first on the error. Another error followed as shortstop Ossie Bluege let Hank Gowdy’s double-play grounder through his legs, allowing Wilson to score from second.

Barnes, now with a 3–1 lead, stayed strong. After Harris’s fourth-inning homer, Barnes didn’t allow another runner until he gave up singles to Harris and Goose Goslin in the seventh, but the Senators came up empty as Judge flied out to end the inning.

Art Nehf and Hugh McQuillan began warming up as the Senators came up in the last of the eighth, although it looked like they wouldn’t be needed as Bluege popped out to start the inning. But hits by pinch-hitter Nemo Leibold and Muddy Ruel put runners at the corners. Bennie Tate batted for Marberry and walked to load the bases. Barnes retired McNeely on a low liner to left as the runners held, and it looked as if he had worked his way out of the jam when he got Harris to hit a ground ball toward Lindstrom at third. “Harris didn’t hit the ball hard,” reported the New York Times, “but just as the grounder hit in front of Lindstrom, the pellet took a sudden leap, cleared the fielder’s head by a foot and rolled out to left field.”5 The bad-hop hit scored two runs to tie the score.

After Nehf relieved Barnes, and Rice grounded out to end the inning, the Washington fans roared for two reasons. One was the game-tying rally. The other was for Walter Johnson, who was on his way to the mound for the ninth inning. The Big Train would again get a shot at a World Series win, one that could give his team the championship.

Johnson quickly found himself in trouble, giving up a one-out triple to Frisch. He got out of it, though, by intentionally walking Youngs and striking out Kelly on three pitches. Meusel then hit a grounder to third baseman Ralph Miller, whose erratic throw to first was saved by a great stretching catch by Joe Judge.

Like the Giants, the Senators threatened in the last of the ninth. Judge singled with one out. Bluege grounded to Kelly, who threw to second to try to force Judge. Shortstop Travis Jackson was late in covering, then dropped the throw and had it roll away as Judge made it all the way to third on the error. With Washington needing only a long fly to win, John McGraw went to his bullpen, bringing in McQuillan to face Miller. After taking a ball, Miller hit a sharp grounder. It was right at Jackson, though, who made up for his error by starting an inning-ending double play and preventing the winning run from scoring.

A dramatic inning had failed to produce runs, and the game went into extra innings. The Giants continued to put runners on against Johnson, who continued to work his way out of jams.

As for the Senators, they went down in order in the 10th and got a two-out double by Goslin, followed by an intentional walk, in the 11th off Jack Bentley, New York’s fourth pitcher of the game. Bluege grounded into a force out to end that threat.

Miller grounded out to start the bottom of the 12th. Muddy Ruel lifted a pop fly behind the plate. Giants catcher Hank Gowdy had trouble with the ball from the start. He circled under it, then flung his mask away as he seemed to figure out the spot it would drop. However, at the last instant, Gowdy had to lunge to his right. He might have still made the catch if he hadn’t stumbled over his mask. Nearly falling to one knee, Gowdy dropped the ball.

The error gave another chance to Ruel, who ripped a pitch inside third base for a double. The Giants missed a chance for the second out of the inning when Jackson booted Johnson’s grounder to short, although Ruel had to hold on the play. With one out and the winning run on second base, Earl McNeely hit a sharp grounder toward Lindstrom.

News reports vary on how the ball ended up past the Giants’ third baseman, allowing the winning run to score. Most retrospective accounts describe it as a similar play to Harris’s hit in the eighth, which took a bad hop over Lindstrom’s head. Stories from the time, however, provide other details, some of them contradictory. Washington Post sports editor N.W. Baxter wrote:

The Pacific coast youth [McNeely] met a ball from Bentley. Down the third base line it sped. A momentary shout and then a hush for it was just the sort of ball on which Lindstrom had made a brilliant play and out when the game opened. This time it was not to be. Fortune evidently considered she had done enough for this boy who humbled Walter Johnson and played a real man’s role throughout the series. His outstretched hands missed the ball completely, despite a marvelous dive. Muddy Ruel was in, standing up, with the winning run.6

However it got by, through, or over Lindstrom, the ball made it out to left-fielder Irish Meusel, who held the ball, declining to make even the gesture of an attempt to head off Ruel with a throw home.

The Senators had their championship, Walter Johnson had his victory, and the citizens of Washington rejoiced on Pennsylvania Avenue and elsewhere through the night.9

STEW THORNLEY—who is related by marriage to another author in this publication—has been a SABR member since 1979.

Notes

1 “Baseball Scandal Will Not Interfere with World’s Series,” The New York Times, October 3, 1924, 1.

2 “Johnson Planning to Retire from Box,” The New York Times, October 1, 1924, 15.

3 “Handshakers Urged to Save Johnson’s Arm for the Giants,” The New York Times, October 2, 1924, 18.

4 The 1924 World Series was the first to be played in a 2–3–2 format (the first two games played at one site, the next three, if all were needed, at the other site, and the final two, if needed, at the original site). However, the format was not predetermined. After the teams split the first four, a coin toss was held just before the teams took the field for the fifth game. Washington won the toss, giving it the home field for the final game. “Griffith Wins Toss for Seventh Game,” The New York Times, October 9, 1924, 18. The 1925 World Series was the first to adopt the 2–3–2 format, which has been used in all Series since, except for a 3–4 format used in 1943 and 1945 because of travel restrictions during World War II. For more on the topic, see “The Evolution of World Series Scheduling” by Charlie Bevis, 2002 SABR Baseball Research Journal, 21–28.

5 “Senators Win World Championship, Johnson Pitching Them to Victory over Giants, 4 to 3, in 12-Inning Battle,” The New York Times, October 11, 1924, 9.

6 N. W. Baxter, “Johnson Is Hero as Nationals Win Decisive Game of World Series, City in Carnival, Celebrates Victory,” Washington Post, October 11, 1924, 5.

7 “The Johnson of Old Too Much for Giants,” The New York Times, October 11, 1924, 9.

8 “Senators Win World Championship, Johnson Pitching Them to Victory over Giants, 4 to 3, in 12-Inning Battle,” The New York Times, October 11, 1924, 9.

9 In 2014, the Library of Congress revealed a digital copy of a newsreel with footage of the final game of the 1924 World Series. According to an article at https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/library-congress-obtains-rare-1924-world-series-footage, the film was found in the garage of a resident of Worcester, Massachusetts, who had died in 2013. A few minutes of the footage are available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kUX9QZo_jX8 and contain some images of Walter Johnson pitching. Viewers should be alert to the footage not always lining up with the descriptions, such as one of George Mogridge pitching (the pitcher shown, unlike Mogridge, is right-handed).