Chicago’s Other ‘Big Ed’

This article was written by John McMurray

This article was published in SABR Deadball Era newsletter articles

This article was published in the SABR Deadball Era Committee’s November 2023 newsletter.

Ed Reulbach is remembered principally for three things: for his five-year run of pitching success for the Chicago Cubs between 1905 and 1909; for his then unprecedented one-hit game in the 1906 World Series; and for shutting out the Brooklyn Superbas in both games of a doubleheader during the 1908 pennant race. His successes invite recollection of this Deadball Era figure whose career shone exceptionally bright during the period’s first decade.1

Ed Reulbach is remembered principally for three things: for his five-year run of pitching success for the Chicago Cubs between 1905 and 1909; for his then unprecedented one-hit game in the 1906 World Series; and for shutting out the Brooklyn Superbas in both games of a doubleheader during the 1908 pennant race. His successes invite recollection of this Deadball Era figure whose career shone exceptionally bright during the period’s first decade.1

Described by David L. Porter in the Biographical Dictionary of American Sports as both “a superlative pitcher” and as “brainy,” Reulbach was among the elite pitchers of his day, with strong statistical parallels to Pittsburgh’s Sam Leever.2 Both Reulbach and Leever pitched for thirteen seasons in the National League, each led the league in won-loss percentage three times, and both won roughly two-thirds of their respective pitching decisions. Yet Reulbach’s peak was undeniably higher, with Ed’s ERA being under 2.00 in four of his first five seasons and Reulbach’s three straight seasons of leading the league in winning percentage has been equaled in baseball history by only one other pitcher: Lefty Grove.3

Surely, as Cappy Gagnon recounts so deftly in Deadball Stars of the National League, Reulbach’s relative lack of renown stems from being perpetually overshadowed. Reulbach likely ranked second or third on a Cubs pitching staff led by Mordecai Brown which also included Orval Overall (himself a similar pitcher to Reulbach), Jack Pfiester, and Carl Lundgren. Reulbach’s remarkable achievements aside — such as a 20-inning complete game victory against Philadelphia in 1905 — Reulbach was never the best pitcher in the city of Chicago during his own career, firmly landing third behind Brown and Ed Walsh of the crosstown White Sox. Adding some insult to injury, Reulbach was, as Gagnon notes, not even the best “Big Ed” in his own city, losing out on that distinction too to Walsh (even if both were roughly 6’1”).4

Is there another elite performance more often forgotten than Reulbach’s World Series one-hitter in 1906? With the Cubs having lost Game 1 to the upstart White Sox, Reulbach’s top-level effort in Game 2 came at a time when the Cubs needed it most. Though Reulbach did yield an unearned run in that game — on account of his own wild pitch and a Joe Tinker error — the right-hander gave up only one hit, a seventh-inning single to center by Jiggs Donahue. Reulbach’s six walks aside, it was surely one of the greatest World Series games pitched during the Deadball Era. Reulbach also squeezed home a run in support of his own victory.

Still, when Monte Pearson of the New York Yankees pitched a two-hit complete game in Game 2 of the 1939 World Series against the Cincinnati Reds, Reulbach’s World Series one-hitter came under review. At issue was the first play of the fourth inning of that game in 1906, where Fielder Jones reached on a two-base error by Johnny Evers. A book edited by George L. Moreland titled Balldom, according to a 1939 published piece, noted that “every Chicago paper” the next day “showed that two hits were charged against the husky Chicago hurler.” Tribune sportswriter I.E. Sanborn apparently said that “Jones hit an ugly bounder between first and second that went for a double.” If true, Pearson would have equaled Reulbach’s feat for a low-hit World Series game.5

A 1961 obituary of Reulbach written by Fred Lieb noted the controversy, saying that the Chicago Tribune credited the White Sox with two hits in Game 2, but the official score complied by A.J. Flanner of The Sporting News and Francis Richter of Sporting Life gave the White Sox only one hit, a single by Jiggs Donahue.”6 Most accounts cite Sanborn as the primary source of the discrepancy. Evers, responding to a query from sportswriter Mike Gaven years later, noted: “Ball hit to me by Fielder Jones was very bad fumble by me, and it was charged as an error. Remember it very distinctly, like all youngsters remember their first important game.”7 At the time, the National Commission ruled it to be a one-hitter and so it has remained. This tempest in a teapot more than three decades later may have chipped away a bit at the distinctiveness of Reulbach’s achievement.

Reulbach’s two shutouts in a doubleheader could not have come at a better — or, from the perspective of recognizing Reulbach’s achievement, more vexing — time. In close competition with both the New York Giants and the Pittsburgh Pirates for the pennant, the Cubs knew they needed to win both games to remain in close contention and turned to Reulbach, who often dominated the hapless Superbas. In the first game, according to Bill Gottlieb in a 1942 article in the Brooklyn Eagle, Brooklyn starter Kaiser Wilhem “never had a chance against the superlative pitching of his opponent” in a 5-0 Cubs victory during which Reulbach retired the last fifteen batters consecutively.8 As Lee Allen noted in a 1968 article, with the first game taking only 1:40, Reulbach then talked Frank Chance into letting him pitch the second game, which itself took only 1:15.9

The second contest, against Jimmy Pastorius, then with a 3-19 record, pitching for Brooklyn, was tighter. Upon the conclusion of the second game — a 3-0 Cubs win — Reulbach had pitched thirty consecutive scoreless innings. But Reulbach’s unmatched achievement was dulled by its timing since it came only three days after the Merkle game, the central event of the 1908 season. Reulbach’s singular moment has, in some sense, been lost to posterity in the wildest pennant race in baseball history. In Cait Murphy’s Crazy ’08, an authoritative history of that season, Reulbach’s doubleheader shutout is summarized on less than a single page.

Like Hippo Vaughn, Jack Coombs, and Deacon Phillippe, Reulbach is respected but not well known. He has been, fairly or unfairly, lumped into the group of workmanlike starting pitchers integral to team success but never considered consistently dominant. Though known as a practical joker at Notre Dame, his opacity on a personal level derives some too from playing under three assumed names before reaching the major leagues. It no doubt hurts Reulbach’s cause that he never pitched more than 300 innings in a season during a time when it was relatively common to do so. Except for a 20-win season for the Newark Peppers of the Federal League in 1915, Reulbach’s final eight professional seasons were, at best, good and never great.

Ed spoke of the competition of his era in a 1944 interview with sportswriter Al Laney:

I have not seen a baseball game since 1922,” said Reulbach, “so I am not qualified to speak of the present day. But I love to talk about the old days. Distance probably gives them a value in our minds that they don’t have. But they seem like wonderful days now. I wonder if the team spirit is as great these days. I doubt it. The team was everything then. We didn’t bother so much about our individual averages, but if anybody smiled in the clubhouse after we were beaten, he was likely to get a stool draped around his neck. We hated those Giants, and we were ready to fight them on the field and off. The fans hated, too, in those days. We weren’t always safe on the streets of New York, and neither were the Giants in Chicago.10

In an interview with the New York Journal-American in 1946, Reulbach, like many pitchers of his day, admitted to throwing a mud ball:

Beat National League clubs with it for years, and they never caught me throwing it,” said Reulbach. “I would load the glove with saliva before the previous pitch, which I would waste. Then when the ball landed in my glove it was soaking wet. Then all I had to do was drop the ball in the dry dirt and I had my mud ball. You talk about experiments. That’s the trouble with pitchers today. They don’t experiment enough. Every few days I took home a couple of balls and bounced them on the sidewalk. Every batch of balls was different. One week they would be lively, and the next shipment would be dead. I pitched accordingly.11

A recurring theme in articles about Reulbach’s career is that he was overshadowed, whether it be by the star power of his pitching contemporaries, the timing of his two shutouts in a doubleheader, and even by the timing of his own death, as Reulbach died within hours of Ty Cobb. More so, the issue appears to be that that Reulbach’s career was ascendant for a relatively brief period and that fans do not have as much of a window into Reulbach the person as they do for many of his contemporaries. Reulbach’s career is a testament to quiet efficiency and occasional transcendence. While Reulbach has not been elected to the Hall of Fame, the history of the first decade of the Deadball Era cannot be written without him mentioned as a central figure. That, in and of itself, is good enough.

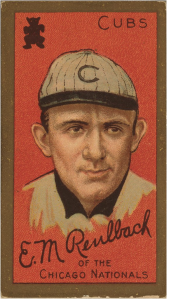

Photo credit

1911 T205 Ed Reulbach Piedmont baseball card, Trading Card Database.

Notes

1. With thanks to the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame for providing article clippings cited in this article.

2. Porter, David L. ed., Biographical Dictionary of American Sports. Undated clipping from Reulbach’s player file at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

3. Statistics in this article are courtesy of baseball-reference.com.

4. Simon, Tom, ed. Deadball Stars of the National League (Society for American Baseball Research: 2004), pp. 111-112.

5. “A Lighter Topic.” Unattributed clipping from Reulbach’s Hall of Fame file dated October 13, 1939.

6. Lieb, Fred, “Ed Reulbach, Star Twirler of Early Cubs Champs, Dead,” The Sporting News, July 26, 1961, p. 36.

7. “Evers Settles Dispute.” Unattributed clipping from Reulbach’s Hall of Fame file dated October 12, 1939.

8. Gottlieb, Bill, “Ed Reulbach’s Double Shutout in 1908 Still Stands as Record,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 29, 1942.

9. Allen, Lee, “How Many Shutouts in ’08?” The Sporting News, September 14, 1968, p. 6.

10. Laney, Al, “Ed Reulbach in There Pitching, Helping to Shut Out Axis at 61,” New York Herald-Tribune, January 16, 1944. No page number given.

11. Gaven, Michael, “Modern Pitchers Lack Initiative Says Reulbach on Visit to Frick,” New York Journal-American, January 25, 1946, p. 20.