Gavy Cravath’s Hall-Worthy 200 Home Runs

This article was written by Rick Reiff

This article was published in Fall 2024 Baseball Research Journal

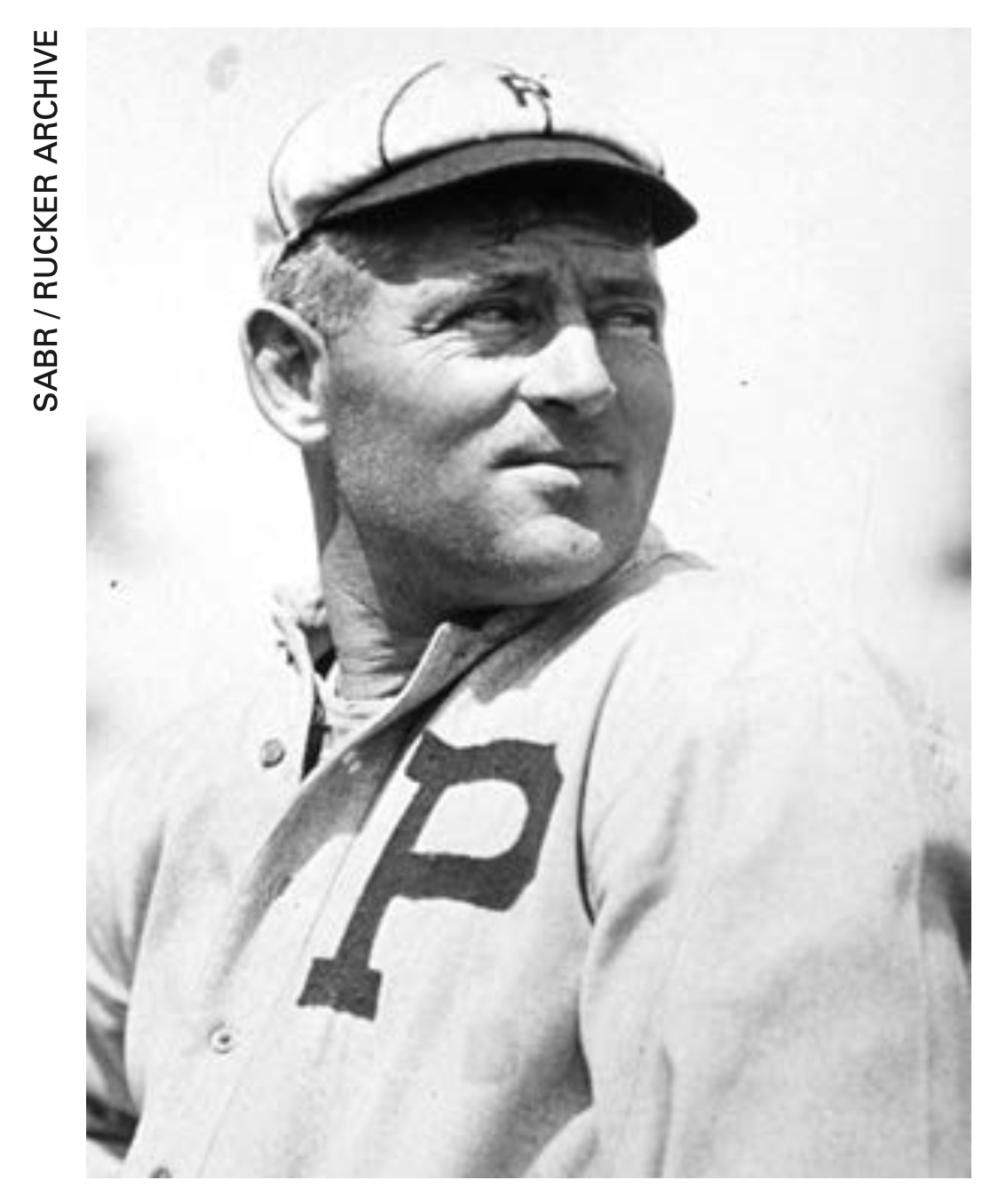

Gavy Cravath led the National League in home runs six times in seven seasons. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

What more is there to say about Clifford Carlton “Gavy” “Cactus” Cravath, the enigmatic Deadball Era slugger relegated to the dustbin of baseball history by George Herman Ruth? How about this: He was likely the first player to hit 200 home runs in affiliated baseball. Babe Ruth was, of course, the first to 200 homers in the majors (and first to 300, 400, 500, 600 and 700), but Cravath, whose 20-year career was split almost evenly between the majors and minors, was almost certainly the first to reach 200 counting all leagues. His numbers are there in the record book—119 homers in the majors, 107 in the minors, and seven in the 1903 “independent” Pacific Coast League.

Yet this accomplishment has seldom been acknowledged—at least not for the past 100 years. In August 1920, The Sporting News asserted that Cravath’s career home run total, which it reckoned at 218, “still holds out a challenge to the Babe.”1 (Babe met the challenge late in the 1923 season, just months after Cravath retired.)2

Cravath’s 233 homers, 210 of them collected in the pre-1920 Deadball Era, should cement his status as the greatest home-run hitter before Ruth. It puts him well ahead of Roger Connor, the Hall of Fame nineteenth century slugger whose 138 big-league blasts are often cited as the pre-Ruth standard; adding his known minor league homers only gets Connor to 148.

And it begs the question, why the heck isn’t Cravath in the Hall of Fame already? As with many things Gavy (nearly always spelled Gavvy by the press, but Cravath himself preferred a single “v”) the question spurs debate.3 Let’s start with some facts in Cravath’s favor.

- He dominated the home-run category as no player before him.

- He set the twentieth century single-season homer mark in the majors (24 in 1915), nearly matched the minors mark with 29 in 1911 (Ping Bodie had 30 in 1910), held the twentieth century’s career homer mark before Ruth, and was the big bat on Philadelphia’s first and only National League pennant winner in a 67-year span.

- He led the National League in home runs six times and the majors four times. Counting the American Association, he won eight home run titles in 10 seasons and missed making it 10 straight by just four homers.4 From 1912 through 1919 he led all of major league baseball in home runs (116) and RBIs (665) and led the National League in total bases, slugging average, and on-base plus slugging average (OPS).

Even in Ruth’s breakout year of 1919, an aging Cravath’s performance was notable. His National League-leading 12 home runs were a distant second to Babe’s record-shattering 29, but were compiled in only 214 at-bats. Applying Cravath’s homer percentage to the same number of plate appearances as Ruth would’ve had the leaderboard at Ruth 29, Cravath 25, everyone else 10 or fewer.

As Ruth was en route to hitting an astronomical 54 homers in 1920, The Sporting News trumpeted Cravath as “the real champion” but conceded, “The Babe may in time make even Cravath’s record look sick.”5 In the era of the lively ball, it didn’t take long.

Yet Cravath also showed what he, too, could do with the live ball. As a 40-year-old playing manager for the Pacific Coast League’s Salt Lake City Bees in 1921 and 41-year-old pinch hitter for the American Association’s Minneapolis Millers in 1922, he posted modern-style power numbers: 22 home runs in 431 at-bats, a .316 batting average, and .527 slugging average.

Modern metrics also put Cravath in exclusive company. His ballpark-adjusted 151 OPS+ (meaning no Baker Bowl distortion, which will be addressed shortly) places him 38th all-time (tied with Honus Wagner and ahead of most Hall of Famers), and 14th among players from age 31 (ranking between Willie Mays and Hank Aaron). His OPS+ for 1912–19 leads all National Leaguers and trails only Ty Cobb, Ruth, Tris Speaker, and Joe Jackson. He twice led National League position players (excluding pitchers) in Wins Above Replacement (WAR). His Offensive Wins Above Replacement (oWAR) of 28.7 from 1912–17 is best in the league.

Baseball historian and statistical analyst Bill James has ranked Cravath as the third-greatest right fielder from age 32–36, after Ruth and Aaron.6 So the question becomes, why isn’t Cravath better appreciated?

Here are the main arguments made against him, which we’ll address in turn:

- He spent too much time in the minors.

- His first big-league trial was a flop.

- He hit a lot of cheap homers at Baker Bowl.

- He seldom homered on the road.

- He bombed in his only World Series.

- He was a one-dimensional player: couldn’t field, couldn’t run.

SPENT TOO MUCH TIME IN THE MINORS

Cravath had a truncated major-league career. He didn’t make it to the majors until he was 27 and initially failed to catch on, returning to the minors and not becoming a big-league regular until he was 31. His big-league numbers, including WAR of 33, are impressive for being compiled in the equivalent of only eight seasons, but fall short of the usual Hall of Fame standards. But Cravath’s prolonged time in the minors is a reflection of how baseball operated in the early 1900s, not a verdict on his ability.

The minors weren’t “minor league” as the term applies today. Stringent draft rules, the majors’ Northeast US orientation, and competitive salaries kept many talented players in the minors for much or all of their careers. The Midwest-situated American Association, where Cravath thrived, was particularly strong, with rosters dominated by major leaguers on the way up or down.7 The high stature of minor league ball was reflected in the iconic T206 series of tobacco cards, issued from 1909 to 1911. A fourth of the entire set, 134 cards, depicts minor leaguers—among them “Cravath, Minneapolis.”8

“On the whole the leading clubs of the American Association could give battle on even terms to the second division teams of the majors,” Baseball Magazine editor F.C. Lane wrote in 1914.9 A newspaper story reporting on Cravath’s 1912 signing with the Phillies observed that “outside of the major leagues the American Association boasts of the best twirlers in the land.”10

If the Pacific Coast League, where Cravath spent five formative and productive seasons, had not yet earned its reputation as “the third major league,” it was already a respected feeder of West Coast talent to the “eastern” leagues. Cravath’s teammates on the Los Angeles Angels included past, present, and future major league stars in Dummy Hoy, Frank Chance, Hal Chase, and Fred Snodgrass.

Cravath’s major league record is missing what was arguably his peak: 1910 and 1911, when at ages 29 and 30 he tore up the American Association. “No one can tell me that I wasn’t hitting well enough for a berth in the majors at that time,” Cravath recounted for Baseball Magazine in 1918. “I know I was. I was hitting then better than I can now…I finally managed to slug my way back into the Majors, but three years were gone.”11

Big league teams wanted him, but draft rules bound him to Minneapolis. American Association clubs, Lane wrote, “have frequently, in pursuit of their own best business interests, found it advisable to smother talent which would have found a freer expression in the very highest circuits of the country, as in the case of Cravath.”12

FIRST BIG-LEAGUE TRIAL WAS A FLOP

Cravath entered the majors in 1908, fresh from being chosen his PCL team’s Most Valuable Player.13 Fourteen months later he was back in the minors. In 94 games with the Boston Red Sox in 1908 he batted .256 with a single home run. In 22 games for the Chicago White Sox and Washington Nationals in the spring of 1909 he batted .161.

Even Cravath admirer Lane declared, “He was the property of three American League clubs in succession…failing to make good in every case.” Nearly 90 years later Bill James rendered the same verdict: “He failed trials with Boston, Washington, and Chicago in the American League due to illness, injuries, and competition from other new acquisitions like Tris Speaker and Clyde Milan.”14 Cravath himself expressed disappointment with his performance, blaming it in part on not being played regularly.15

But look again: If his wasn’t a stellar debut, in the context of the Deadball Era it was still a solid rookie showing. Cravath’s 1908 batting average was 17 points higher than the league average. He hit 11 triples to go with the one homer. His .737 OPS was a significant 139 points above the league average and second-highest on the Red Sox. Despite playing only part-time, he compiled 1.7 WAR, fourth-best among Boston non-pitchers.

His brief stint with Chicago, often described as a “slow start,” contained hidden gems: 19 walks in 19 games, a robust .406 on-base percentage, and one of only four home runs the White Sox would hit all year. “That dreadful and historic bat of Cravath’s is still pulling the Sox out of tight places,” the Los Angeles Herald reported in early May. “It isn’t so much the hitting he is doing as the opponents’ fear of what he might do. Consequently, the pitchers keep passing him…”16

The newspaper expressed disbelief when White Sox owner Charles Comiskey shipped him to Washington in a multi-player trade: “That Cravy, stick marvel that he is, should be let go by Comiskey, when the Windy City papers have been filled with wonderful accounts of his timely hitting and steadiness, and one scribe even went so far as to remark that ‘Cravath can hold center garden for the rest of his life if he desires,’ comes as a shock to his friends and admirers in Los Angeles…Cravath may give Comiskey cause for regret that he let him go, for the stocky slugger seems ripe for sensational performance.”17

It’s debatable whether Cravath’s return to the minors after a 15-day, three-game stop in Washington was even a demotion. The Nationals were on their way to 110 losses and manager Joe Cantillon was on his way out. But Cantillon owned a piece of the Minneapolis Millers, which were operated by his brother Mike. In a blatant but legal conflict of interest, Joe sent Washington players to Minneapolis to help Mike assemble an American Association powerhouse. The next season, Joe took over as the Millers manager and won three straight championships.18

“When I went to Washington the club was in sad shape,” Cravath told Lane. “[Joe Cantillon] told me from the first that he intended to take me to Minneapolis with him.”19

Cravath’s 1909 AA season was solid, 1910 and 1911 were spectacular. He led the league in homers, doubles, hits, and total bases both seasons. Cravath, a right-handed batter, is said to have honed an opposite-field stroke to take advantage of his home Nicollet Park’s short right field and high fence—a configuration uncannily similar to that of Baker Bowl, which he was soon to master.20

In the 1912 pre-season several big-league teams vied for Cravath, including the White Sox, apparently undeterred by his supposedly disappointing 1909 audition.21 The ensuing skirmish required the intervention of the National Commission, which seized upon an apparent clerical error to free Cravath from his Millers contract and award him to the Phillies.22

This time he was in the majors to stay.

CHEAP HOMERS IN BAKER BOWL

A disproportionate 78% of Cravath’s major league homers, including all 19 of his major league-leading 1914 clouts, were hit in his “cigar box” home ballpark.23 But was Cravath lucky or was he opportunistic? From 1912 through 1919 he hit a fifth of the Baker Bowl homers with less than a twentieth of the plate appearances. Cravath hit 60% as many homers as all visiting teams put together. About half of his shots went over Baker Bowl’s 40-foot right-field wall, a mere 279½ feet down the line and about 320 feet in the power alley.24 That was an inviting target for left-handed batters but required opposite-field power from Cravath.

He bristled at the critics: “If I could drop a lot of home runs over that fence there was nothing to prevent a good many other sluggers who have been on the club the past many years from doing the same,” Cravath said. He added, “That right-field fence isn’t always a friend…I have hit that fence a good many times with a long drive that would have kept on going for a triple or a home run.”25

SELDOM HOMERED ON THE ROAD

This is a corollary to the above argument: Take away Baker Bowl, you take away Cravath’s power. Indeed, he only hit 26 road homers. But that figure, paltry as it looks, typifies sluggers of the 1910s (Ruth excepted). Cravath’s percentage of road homers to plate appearances slightly trails Joe Jackson and Ty Cobb, roughly matches Frank Schulte, and exceeds Home Run Baker, Heinie Zimmerman, Larry Doyle and teammates Fred Luderus and Sherry Magee.

And note that Cobb hit 46 inside-the-park homers, a whopping 39% of his career total; Cravath only hit four. Perhaps big parks benefited the fleet-footed Ty as much as a small park helped Gavy.

BOMBED IN HIS ONLY WORLD SERIES

One postseason shouldn’t define a career. But the 1915 World Series was indeed a disappointment for the record-setting home run champ. Cravath in 16 at-bats managed only two hits and no homers and struck out six times as the Phillies fell to the Boston Red Sox in five games. In the first inning of the final contest he came to bat with the bases loaded and none out and grounded into a pitcher-to-catcher-to-first double play. (Later accounts would even claim that Cravath pulled a “boner” by bunting on a full count, a description unsupported by contemporaneous newspaper stories.)26

Cravath’s struggles—reporters’ creative epithets for him included “fat baboon,” “rich-hued lemon,”27 and “a plain bust”28—were contrasted with the stellar all-around play of Boston outfielders Harry Hooper and Duffy Lewis, who between them hit three homers in Baker Bowl.29 Phillies manager Pat Moran came to Cravath’s defense, telling the Washington Times that his slugger “was all crippled up, and I know lots of ball players that would not have even attempted to play with their legs in the condition Gavvy’s [sic] are.”30

Still Cravath displayed his power, but this time in the wrong ballpark: the new, cavernous Braves Field, where the Red Sox moved their World Series home games because it had more seats than Fenway Park. “Cravath got three blows that in Philadelphia would have been home runs,” Grantland Rice wrote.31 William A. Phelon seconded the observation: “Cravath, single-handed, would have won the series at almost any other ballyard in the land, for three of his gigantic flies were pulled down by the Boston outfielders so far from home that they were sure home runs on other grounds.”32 By contrast, Hooper and Lewis’ homers didn’t even make it out of Baker Bowl—they landed in the temporary outfield seats.33

Nor was Cravath entirely unproductive: His hits were a double and a triple and he drove in the go-ahead run in the Phillies’ lone victory. The Red Sox respected the right-handed-batting Cravath to the end, keeping their brilliant young southpaw Babe Ruth off the mound.34

A ONE-DIMENSIONAL PLAYER

Cravath was slow. He admitted as much.35 But he wasn’t Ernie-Lombardi slow–he averaged almost 10 triples and 10 stolen bases a year. In his early PCL days he might even have been fast, as evidenced by 183 stolen bases over five seasons. A simple explanation for his lack of speed is that by the time he got to Philadelphia he was 31, already aging in baseball years.

In the field he wasn’t Dick-Stuart bad. He threw well, three times leading National League outfielders in assists. In 1913 Baseball Magazine described him as “an earnest and industrious worker” in the field.36 But most contemporary accounts disparage his fielding.37 That aligns with his -9.5 Defensive WAR (dWAR).

Yet how much should those shortcomings count against him? The Hall of Fame includes other sluggers who didn’t run or field well—Ralph Kiner, Harmon Killebrew, Jim Thome, and “Big Papi” David Ortiz to name a few. They’re honored for what they could do, not for what they couldn’t.

But unlike them, Cravath played before his time— a long-ball hitter in a low-scoring era that lionized speed and defense and measured offense almost exclusively by batting average. Today he’s lost in time—too ancient to interest most baseball fans, captured only in a few black-and-white photographs and tethered to shoulder-shrugging dead-ball stats.

Historians and statisticians have tools to rectify misperceptions. The more we study Cravath, the better his chance to someday make the Hall.

CONCLUSION

Even though advanced metrics were many years away, some peers intuited that Cravath’s value wasn’t being accurately gauged. Prescient articles in Baseball Magazine featured Cravath as Exhibit A for why the game needed a better offensive statistic than batting average. “Jake Daubert, reckoned on any sane basis, is not equal to that of Cactus Cravath by a very wide margin. In fact, the two are not in the same class,” Lane wrote in 1916. “And yet, according to the present system, Daubert is the better batter of the two. It is grotesqueries such as this that bring the whole foundation of baseball statistics into disrepute.”38

Lane, anticipating Bill James’ Runs Created formula, proffered a system that gave weighted run values to singles, doubles, triples, and homers and used it to show that Cravath was 42% more productive than Daubert in 1915, even though Daubert had out-hit Cravath .301 to .285.39 (Lane’s formula holds up well: More than a century later, Baseball Reference’s Runs Created per Game measure, (RC/G), gives Cravath a 52% advantage).

John J. Ward wrote in 1918 that Cravath “has suffered more than any other player now in baseball from the absurdity of a system which gives a batter as much credit for a scratch single as for a home run with three men on bases…Long considered by the pitchers the most dangerous hitter in his circuit, he has never yet received the recognition which is his due or the proper rewards to which his talents have entitled him.”40

Ward said that in a “system built upon total bases” the .280-hitting Cravath topped Edd Roush, Zack Wheat, Heinie Groh and every other .300-hitting National Leaguer in 1917.41 Ward’s “system” would later have a name: slugging average.

Cravath argued his case colorfully: “Short singles are like left-hand jabs in the boxing ring, but a home run is a knock-out punch…Some players steal bases with hook slides and speed. I steal bases with my bat.”42

But it took Ruth to make home runs the coin of the baseball realm. The game moved on from Cravath and Cravath moved on from baseball. He returned home to Laguna Beach, California, invested in real estate, enjoyed fishing and lawn bowling, and, despite the lack of a law degree, spent decades as the elected justice of the peace. When he died in 1963 at age 82 some locals were surprised to learn that Judge Cravath had once been a baseball star.43

The Hall of Fame has no plaque for Cravath, but it does have a file on him that includes a questionnaire he filled out many years after his last game. One of the questions was, “If you had it all to do over, would you play professional baseball?” Cravath’s terse response knocked it out of the park: “At present prices yes.”44

RICK REIFF is Editor at Large of the Orange County (California) Business Journal. He lives in Gavy Cravath’s hometown of Laguna Beach, roots for and suffers with the American League franchises in Chicago, Cleveland, and Anaheim, and cherishes his 1959 Topps Keystone Combo (Fox-Aparicio) baseball card. He has written thousands of news stories. This is his first article for SABR.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Baseball Reference’s databases and their Stathead research engine, which were used extensively for statistics in this article. Also thanks to William Victor, who crunched some of the numbers. And thanks to SABR’s online newspaper archives, the Library of Congress’ digitized newspapers, and the Giamatti Research Center of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, and the Laguna Beach Historical Society for most of the news and magazine citations.

NOTES

1 “Here’s the Real ‘Champion,’” The Sporting News, August 19, 1920, 3. The article credited Cravath with seven more home runs at that point in his career than does Baseball Reference.

2 According to Baseball Reference, Ruth hit his 234th professional home run on September 13, 1923. Cravath’s career total was 233.

3 Sportswriters seem to have universally preferred “Gavvy,” but it is well documented that Cravath always spelled his nickname “Gavy,” including in his signature as a judge in Orange County.

4 Baseball Reference. Cravath was one shy of the National League home run crown in 1916 and three short in 1912.

5 “Here’s the Real ‘Champion,’” The Sporting News.

6 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2001), 807.

7 Baseball-Reference. One-time major leaguers comprise roughly three-fourths of 1910 American Association rosters.

8 “1909–11 White Border T206 Guide,” Throwback Sports Cards, https://www.throwbacksportscards.com/1909-11-t206-tobacco-baseball-card-set.

9 F.C. Lane, “Cactus Cravath, the Man Who Started Late,” Baseball Magazine, June, 1914, 32.

10 “Western Phenom Signs with Phils,” 1912, unidentified newspaper clip in the Gavvy Cravath player file, Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, NY.

11 “Cactus” Cravath, “What the Batting Records Have Cost Me,” Baseball Magazine, July, 1918.

12 Lane, “Cactus Cravath,” 32

13 Although some references, including obits, state that Cravath won the PCL MVP Award, the award was not first given until 1927.

14 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Abstract, 807.

15 Lane, “Cactus Cravath,” 28.

16 A.E. Dunning, “Timely Topics,” Los Angeles Herald, May 4, 1909, 4.

17 A.E. Dunning, “Timely Topics,” Los Angeles Herald, May 17, 1909, 6.

18 Terry Bohn, “Joe Cantillon,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/joe-cantillon/.

19 Lane, “Cactus Cravath,” 28.

20 Bill Swank, “Gavy Cravath,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/gavy-cravath/.

21 Ernest J. Lanigan, “Gavvy Might Break Home Run Mark If Played More,” undated newspaper clipping, Gavvy Cravath player file, Giamatti Research Center; “Outfielder Cravath Is Awarded to Phillies,” undated newspaper clipping, Gavvy Cravath player file, Giamatti Research Center.

22 “Outfielder Cravath Is Awarded to Phillies.”

23 “Baker Bowl was often described as ‘tiny’ and frequently laughed at as a ‘cigar box’ or ‘band box.’” Lost Ballparks, Lawrence S. Ritter, 1992, 10.

24 Accounts vary of Baker Bowl’s precise dimensions in the 1910s, but there is agreement that the distances to right field and right-center field were short and the fence/wall was high.

25 Cactus Cravath, “The Secret of Home Run Hitting,” Baseball Magazine, July, 1917.

26 In December 1915, Baseball Magazine ’s Wm. A. Phelon described the play as a bunt. In the December 2, 1926, The Sporting News’ Jim Nasium (pen name of Edgar Forrest Wolfe) said it was a bunt and one of the “historical boners of baseball.” The Sporting News even mentioned the episode in its June 8, 1963, obituary of Cravath, adding that it was manager Pat Moran who called for the surprise play. But not a single game-day story examined for this article mentioned a bunt. It was described as “an easy grounder” by the New York Tribune, “a bounder” by the New York Evening World and Washington (DC) Evening Star, “Cravath rolled to Foster” by the Richmond Times Dispatch, “a flabby little hopper” by the New York Sun, and “hit to the pitcher” by the Washington Times.

27 Wm. A. Phelon, “How I Picked the Loser,” Baseball Magazine, December, 1915.

28 William B. Hanna, “Red Sox Earn 1915 Baseball Championship,” The (New York) Sun, October 14, 1915, 10.

29 Phelon, “How I Picked the Loser.”

30 Pat Moran, “Manager of Phillies Admits He is Disappointed,” Washington Times , October 14, 1915, 13.

31 Grantland Rice, Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger, October 14, 1915, 11.

32 Phelon, “How I Picked the Loser.”

33 Phelon, “How I Picked the Loser.”

34 Swank.

35 “You know, I am not much of a base runner. They call me leaden footed, and I admit it.” F.C. Lane, 1914, 108.

36 “The All-American Baseball Club,” Baseball Magazine, December, 1913.

37 One of many examples: “His fielding and his base running have never been above mediocrity.” F.C. Lane, 1914, 116.

38 F.C. Lane, “Why the System of Batting Averages Should Be Changed,” Baseball Magazine , March, 1916.

39 Lane, “Batting Averages,” 1916.

40 John J. Ward, “The Proposed Reform in Batting Records,” Baseball Magazine, July, 1918.

41 Ward.

42 Lane, “Cactus Cravath,” 31.

43 Swank.

44 Gavvy Cravath player file, Giamatti Research Center. The center said the undated questionnaire is from the early 1960s.