Sandy Koufax: Life After Retirement

This article was written by Paul Browne

This article was published in Sandy Koufax book essays (2024)

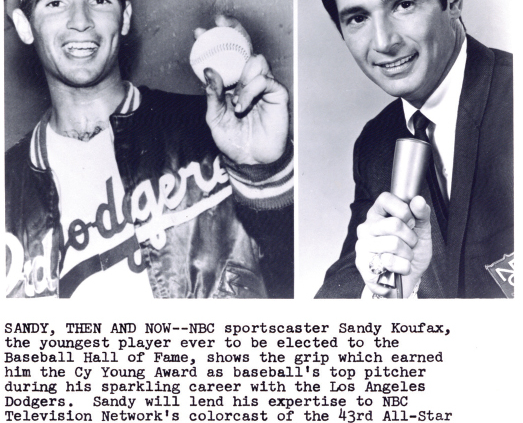

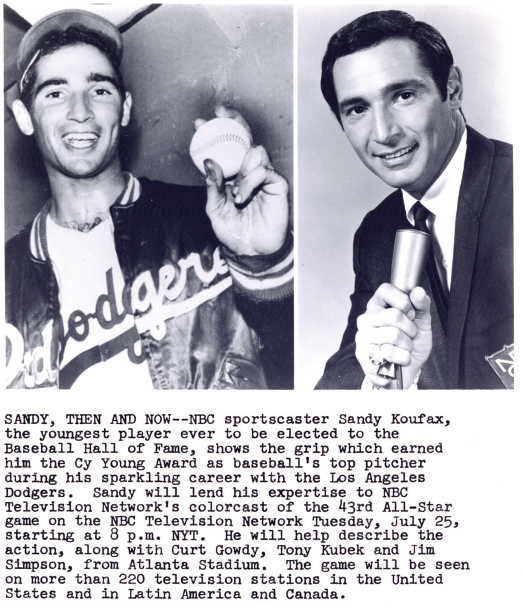

Sandy Koufax shared his baseball insight on the NBC Game of the Week after retiring from the Dodgers. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

When Sandy Koufax retired on November 18, 1966, many people were surprised. Not Buzzie Bavasi–the Dodgers pitcher had told him over the phone the day before. Others within the organization probably had at least an inkling.

Dick Tracewski knew. Roommates while with the Dodgers, Koufax and Tracewski stayed, and continue to stay, close into their late 80s. Koufax had called him after the Dodgers lost the World Series to the Orioles to give him a heads-up about his pending retirement.1

Koufax was just 30 and had had a phenomenal year. Among other records, he led the league in ERA for the fifth consecutive year. Tracewski is pretty sure that will never happen again. “Sandy was not a stats man and he didn’t know he was in line for the record,” he said.2 Former Dodgers teammate Ed Roebuck said, “I think he wanted to get out while he was on top.”3

By the time of his retirement, every sport coat Koufax owned had two different-sized sleeves. His arthritis sometimes swelled to twice the size of his knee. While Koufax had told Bavasi that he wanted to maintain the use of his left arm, Tracewski said the pitcher’s concerns were much deeper. The bottom line was cortisone and a pill. Koufax told Dick that doctors had told him taking those pills could affect his liver, and he wanted to live a long life. The pill was phenylbutazone alka. In Koufax, author Ed Linn says this pill could cause a depleted blood count and that could be fatal.4 This pill is no longer approved for human use in the United States and has been linked to kidney failure in various studies. By the end of the 1966 season, Koufax had enough of risking his health, quality of life, and possibly his life itself. His decision had not been made lightly.

On the day he retired Koufax said, “Right now, I’d guess you’d have to say I’m unemployed.”5 While Koufax may have been able to live comfortably on his savings for a while, Koufax was smart enough to know he needed a job. Enter NBC. On December 30, 1966, his 31st birthday, he signed a 10-year deal for a total of $1 million. The salary of $100,000 per year was better than all but the last two years of his playing career.

Koufax’s first broadcast with the NBC Game of the Week took place on April 15, 1967, the Dodgers playing the Cardinals in St. Louis. The retired star had a 15-minute pregame program, The Sandy Koufax Show, before every episode. He said in the Dodgers dugout, after the interview, “I used to think it was harder to answer questions than to ask them, now I am not sure. During my last five or six years I was never as nervous as I was for this assignment.”6 Early coverage of Koufax’s work in his new career was generous, allowing him a chance to get his feet under him.

Rumors were spreading that July that NBC had offered the job to Koufax prior to his announcing his retirement. “That isn’t true,” Bavasi told sportswriter Bob Addie. “Sandy quit because he meant what he said about his arm. And there was no NBC contract in sight then.”7

While playing a round of golf with a club pro in 1968, “Sandy pushed a shot badly into the rough. ‘No! No!’ commanded the pro. ‘Get that left arm all the way around. Straighten it out.’

‘If I could straighten it out,’ said Koufax, ‘I’d be pitching today instead of playing golf.’”8 Golf was important to him and remained so long into his retirement.

In October 1968 it was reported that Bavasi was trying to get a deal that would allow Koufax to come to San Diego to pitch. Bavasi was now the president of the new Padres.9 Koufax’s response to another story in November put the possibility of a comeback to rest. “Ridiculous” is the way he summed up a comeback. “I have no intention of returning to baseball,” he said. “Trying to pitch again would only make my arm worse. I made my decision to call it quits without a job, now I have one. It would be ridiculous for me to think of reconsidering.”10

On New Year’s Day in 1969 Koufax married Anne Widmark, daughter of actor Richard Widmark. Ed Gruver tells us that “[w]hen Koufax married Anne Widmark, the couple stepped away from public life. They lived a quiet life, splitting time between homes in Maine and California. Because he had invested wisely during his playing career, Koufax was comfortable financially.”11 The couple had bought a farm in Maine in the fall of 1971. He did much of the work on the farm, and his interests in carpentry, gourmet cooking, and fly fishing suited this rural life. While he may have been retreating from public life, he and Anne enjoyed entertaining friends and neighbors at their Maine home as well as in California.

Tracewski said there is some truth in the idea that the couple was retreating from the world when they bought their Maine property. At the time Koufax met Anne, they were both living in Malibu. They met on the beach and she didn’t even know who he was.12 Six months after meeting, he and Anne were married.

Koufax’s life with Anne probably got the most coverage of his three marriages despite the couple’s efforts to maintain their privacy. They divorced in 1982. Koufax married Kimberly Francis, a personal trainer, in 1985. They remained together until 1998. He married Jane Purucker Clarke in 2008.

Golf was another part of Koufax’s life in Maine where he joined Bucksport Golf Club. Koufax had played in celebrity tournaments going back to his playing days. In 1964 he played in the Bing Crosby National Pro-Amateur Tournament (or the Crosby Clambake). Play in various others continued on and off over the years.

In 1990 he started a 15-year run with golfers Billy Andrade and Brad Faxon’s charity tournament in Rhode Island. Andrade had met Koufax as a college golfer in 1985, working up the nerve to introduce himself to the baseball great while they were both having lunch in Santa Barbara. After turning pro, Andrade and Koufax were both at the Dan Sullivan Pro-Am in Aspen, Colorado. They ran into each other at the driving range and Koufax said he remembered Andrade and had been following his career. Andrade invited him to play in his Rhode Island tournament. He said he could not make it in 1990 but would be there in 1991. Koufax played in two pro-am events a year and Andrade’s was one of them. Echoing comments of others who have maintained long-term friendships with the supposed recluse, Andrade said, “I don’t know the baseball player, I know Sandy the person. It’s been a very, very special relationship.”13

Earlier in Koufax’s life, basketball had been more important to him than baseball. He played high-school basketball before he played baseball, not going out for the latter sport until his senior year. He went to the University of Cincinnati on a basketball scholarship but tried out for baseball his freshman year, attracting the attention of major-league scouts. He had a contract with Brooklyn and a $20,000 bonus before his sophomore year. Koufax continued to be a college basketball fan and became a frequent attendee at the annual Final Four Championships. This despite his conjecture that “it is far from impossible that my traumatic arthritis started when I banged my elbow into one of those iron poles (that held up the basket on the outdoor courts he played on).”14

One event in 1972 brought Koufax fully back into public life for a time. At the end of the required five-year waiting period, the Baseball Writers’ Association of America elected Koufax to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. In his first year of eligibility, Koufax received 344 votes, finishing ahead of Yogi Berra at 339 and Early Wynn (301), the only other players reaching the required 75 percent of the 396 votes cast. At 36, Koufax became the youngest player ever elected and, up to that time, he was only the fifth elected in their first year of eligibility.

Did he expect it? Tracewski said everyone expected it, including Koufax. But some things surprised him. In his induction speech Koufax said, “I’m a little surprised I got as many votes as I did. I didn’t have as many good years as some others in the Hall and I thought that might count against me.”15 This was a part of the humble tone of the speech. He said, “This is the biggest honor I’ve ever been given, not just in baseball, but my life.”16 Pointing out that “Mine was a career that began ingloriously,”17 he expressed his gratitude to Joe Becker, his pitching coach during most of his time with the Dodgers, who pushed him to work hard to become a better pitcher, and to his catchers, naming Roy Campanella and, as particularly important to his career, John Roseboro.18

Koufax retired from NBC and sportscasting in February of 1973. Early coverage of his new career had been somewhat of the “give the new guy a chance” variety as well as the sport and those that covered it showing respect for the pitcher’s accomplishments on the field. As time went on, he improved but was never fully comfortable in his new role and it showed. His knowledge of baseball and judgment and insight about pitchers and pitching made him a good and insightful analyst but something was lacking. The consensus that he was a fish out of water became public after he almost as much as said so himself.

Tracewski had an explanation for that. Despite the phenomenal salary for the time, Koufax hated the job. While the travel is difficult for all in that field, Koufax had an added challenge. He was such a celebrity that he couldn’t go anywhere, even when he and Tracewski roomed together on the road. He was a very private person, and while some stars thrive on the attention and public adulation, it was not for him. While he would have loved to go out for a private dinner or other type of outing with friends, it couldn’t be done.19 Eventually he had enough money, for a time, to explore what he wanted to do next.

In early February 1979, Dodgers President Peter O’Malley announced that Koufax would be rejoining the franchise as a part-time pitching instructor. Koufax would work with both major-league and minor-league pitchers during spring training each year and then make visits to LA’s Double-A and Triple-A franchises to provide additional instruction to those he had worked with in the spring. He maintained that position until 1990.

When asked why he was taking the job, Koufax gave two main reasons. “One, it was hard to stay away from the one thing I had done so well in my life”; and “Two, the way the economy has gone, it had become tough to make ends meet.”20 Koufax was 44 and it seems likely the first reason he gave was at least as much a driving force in his decision as the financial one. He was young enough to do the job but may have been old enough to start wondering how long that would be true.

Koufax’s desire to teach was his motivation for becoming a coach. He said, “Pitching is a branch of learning, no doubt of it. You’re part of a chain that goes back for generations passing the art along. You want to start others off further down the line than you did.” When asked where he was from 1972 to 1979, Koufax said, “Wherever I wanted to be. …”21

Some have speculated that Koufax did his coaching at the minor-league level after spring training because of a desire to maintain a low profile.22 Koufax has always insisted that the recluse thing has been greatly exaggerated. At the time of taking the job, he gave his own explanation: “I’m not so presumptuous as to tell veteran pitchers how to throw. They got to the majors without me. But if I can help them develop a certain pitch, or can do the same with the young fellows, I’ll be happy.”23 Koufax wanted to teach the game he had played so well. The knowledge of baseball and judgment and insight about pitchers and pitching that had been his strong point as an announcer were even greater strengths in his new job.

In 1990 Koufax resigned his position with the Dodgers. He “reportedly resigned because he said he was weary of the job. Dodger officials said he was taking a one-year sabbatical, but Koufax said there was no timeframe involved in the resignation. Sources said Koufax was upset with the Dodgers’ player-development program, which had not produced many prospects in recent years. While Koufax and the Dodgers denied any hard feelings, a source said he wouldn’t be surprised to see Koufax align with another team.”24

Tracewski said Koufax didn’t like the last years with the Dodgers because he couldn’t teach much except about conditioning. He felt he was only a celebrity and the attention because of that made it difficult for him to teach the way he wanted to. Photographers were always taking pictures and he hated it. This made him quit earlier than he would have if he could have really taught.25

Koufax continued to attend major Dodgers events after his resignation as well as other baseball happenings, and did some brief periods of outside coaching of pitchers on other teams.

In March of 1999, Koufax visited the Yankees during spring training. Coach Don Zimmer “told reporters that Koufax’s words carried weight” with pitchers.26 “Pitchers who have been lucky enough to have Koufax counsel them have said that his simplistic approach when coaching is easy to follow and understand,” an observer said.27

Koufax’s visits came to a sudden stop at the end of 2002. In March of 2004, Koufax showed up at the Dodgers’ spring-training facility at Vero Beach again. His appearance sparked excitement among players and coaches alike. Koufax said he hadn’t worked for the Dodgers in 12 years and wasn’t working now. He was visiting friends and talking baseball. Frank McCourt, who had recently bought the team, “said he wants Koufax and other expatriate Dodgers alienated by Murdoch’s crew to return to the fold.”28

The McCourt ownership of the team ended in the franchise’s bankruptcy in 2011. McCourt was able to sell the team out of bankruptcy to a group of investors led by Mark Walter that included Magic Johnson. Koufax took a job as a special adviser to Walter. Koufax would return to working with Dodgers pitchers. Clayton Kershaw was one of the pitchers to benefit from Koufax’s presence with the team. Magic Johnson is reported to have been the one to open discussions with Koufax.29

In February 2016, Koufax made an announcement: “I’m 80 years old and I have retired. I have not quit. I’m still part of the Dodger organization and always will be as long as Mark and Kimbra Walter are a part of ownership. I will do most of what I have done in the past with no official title. I hope all the players, coaches, managers, and everyone else in the clubhouse have successful and healthy seasons with a spectacular ending. See you Opening Day.”30

Koufax and Tracewski continued to be friends throughout the period after his retirement from baseball. Koufax’s wife’s family has ties in Northeast Pennsylvania, which caused him to be a frequent visitor to that area in summers. He and Tracewski would golf at the Scranton Country Club, near where Tracewski lived, at least three or four times a year until recent years. On one occasion Tracewski persuaded 1959 Masters winner Art Wall Jr. to join them in a round.31 Wall was from Honesdale, Pennsylvania, which is close to Scranton. The Koufaxes spent their winters mainly in Vero Beach. They became frequent visitors to games at Dodgers Stadium, especially during the postseason.

Tracewski said Koufax was a special guy and conducted himself quietly and positively. He had his own ideas about how he wanted to live and did so accordingly even when he was an active player and a young man. No one pitched like him. He was his own man.

“One thing about Koufax was that he was 120 percent into pitching. He never played golf during the season because it would interfere with his readiness. Pitch, rest, prepare for his next start was his life in his playing days.”32

Koufax brought this dedication to his craft and the Dodgers to his post-playing days’ work with the team. On June 18, 2022, a statue of Koufax joined that of Jackie Robinson in the center-field plaza of Dodger Stadium, the only two players thus immortalized by the team. Clayton Kershaw, one of the speakers at the dedication, said, “Sandy, one day I hope I can impact someone the way you championed me–you really have–left-handed pitcher or not.33

is the author of The Coal Barons Played Cuban Giants: A History of Early Professional Baseball in Pennsylvania, 1886-1896, published by McFarland & Company, Inc. His article on the Cuban Giants’ first victory over a major-league team appears in Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the Nineteenth Century. His Mundell’s Solar Tips appears in the 2013 National Pastime. Browne has been a member of SABR since the mid-1990s and has had several player biographies posted at the SABR BioProject site. He has also contributed articles to McFarland’s journal Black Ball, SABR’s Nineteenth Century and Minor Leagues committees, as well as local newspapers. Browne is executive director of the Carbondale Technology Transfer Center.

Notes

1 Dick Tracewski, telephone interview, September 8, 2023.

2 For a list of ERA leaders 1878-2023, see https://www.baseball-almanac.com/pitching/piera4.shtml.

3 Edward Gruver, Koufax (Dallas: Taylor Publishing Company, 2000), 213.

4 Sandy Koufax with Ed Linn, Koufax (New York: Viking Press, 1966), 237.

5 Gruver, 213.

6 Bob Hunter, “Sandy Discovers Few Kinks in Mike Delivery,” The Sporting News, April 29, 1967: 15.

7 Bob Addie, “Addie’s Atoms,” The Sporting News, July 29, 1967: 14.

8 Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” The Sporting News, May 11, 1968: 14.

9 “Koufax Hints at Trying for Comeback Next Year,” The Sporting News, October 12, 1968: 18.

10 Bob Hunter, “Sandy Says Nix to Comeback Pitch by Dodgers,” The Sporting News, October 9, 1968: 45.

11 Gruver, 217.

12 Tracewski interview.

13 T.J. Auclair, “How Over-Sleeping Led to Golfer’s Lifelong Friendship with Sandy Koufax,” PGA.com, October 12, 2017. www.pga.com/archive/how-oversleeping-led-golfers-lifelong-friendship-sandy-koufax.

14 Koufax with Linn, 24.

15 Gruver, 223.

16 https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/youngest-elected-baseball-hall-of-famers-sandy-koufax.

17 Janey Murray, “Berra, Koufax Inducted Amid Star-Studded Class of 1972,” baseballhalloffame.org, https://baseballhall.org/discover/inside-pitch/berra-koufax-inducted-amid-star-studded-class-of-1972.

18 Marc Z Aaron, “Sandy Koufax,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/sandy-koufax/.

19 Tracewski interview.

20 Gordon Verrell, “Recluse Koufax Steps Back Into the Game With Dodgers,” The Sporting News, February 17, 1979: 35.

21 Thomas Boswell, “Koufax: Hall of Famer Back in Baseball After Years of Wandering,” Washington Post, March 21, 1979, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1979/03/21/koufax/3139f66f-996a-485f-8cce-8f7671152136/.

22 Tom Verducci, “The Left Arm of God: Sandy Koufax Was More Than Just a Perfect Pitcher,” Sports Illustrated’s 60th Anniversary Issue, August 29, 2014 (originally published July 12, 1999). https://www.si.com/mlb/2014/08/29/sandy-koufax-dodgers-left-arm-god-si-60#gid=ci025584b020042580&pid=sandy-koufax.

23 Melvin Durslag, “Gimmie a Handy Guy Like Sandy,” The Sporting News, March 24, 1979: 14, 16.

24 “Baseball,” The Sporting News, March 12, 1990: 19.

25 Tracewski interview.

26 Gruver, 243.

27 Stacie Wheeler, “Sandy Koufax Will Join Dodgers for Spring Training as Special Adviser to Mark Walter,” Dodgers Way, https://dodgersway.com/2013/01/22/sandy-koufax-will-join-dodgers-for-spring-training-as-special-advisor-to-mark-walter/.

28 T.J. Quinn, “Koufax Ends Grudge, Back at Dodgertown,” New York Daily News, March 7, 2004 https://www.goupstate.com/story/news/2004/03/07/koufax-ends-grudge-back-at-dodgertown/29708514007/.

29 Dylan Hernandez, “Dodgers and Sandy Koufax Team Up Again After Years Apart,” Los Angeles Times, www.latimes.com, January 22, 2013.

30 “Koufax Says He Has Retired,” Los Angeles Times, February 29, 2016.

31 Tracewski interview.

32 Tracewski interview.

33 Jacob Gurvis, “Jewish Baseball Legend Sandy Koufax Immortalized with a Statue,” Times of Israel, June 22, 2022. https://www.timesofisrael.com/jewish-baseball-legend-sandy-koufax-immortalized-with-a-statue/.