Spahn and Sain and Pray for Rain

This article was written by Greg Erion

This article was published in Braves Field essays (2015)

Johnny Sain and Warren Spahn, the subjects of Gerald V. Hern’s poem. (Courtesy of Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection)

One of baseball’s most enduring quotes had its genesis in a short poem written by Gerald V. Hern, sports editor of the Boston Post. His verse forever linked Warren Spahn and Johnny Sain as a two-man pitching rotation to their efforts leading the Boston Braves to the 1948 National League pennant. The piece, capturing a moment in time, appeared on September 14, 1948, in the Post as the Braves were making their final drive toward the championship. Hern’s offering:

“First we’ll use Spahn then we’ll use Sain

Then an off day, followed by rain

Back will come Spahn, followed by Sain

And followed, we hope, by two days of rain”

As originally published, his wording did not contain the more popular “Spahn and Sain and pray for rain” or its variant, “Spahn and Sain and two days of rain” with which baseball fans are familiar. How Hern’s prose came to its present form is of interest, but of greater significance is to ask: How close was his rhyme to events on the field?

This question is not unique to Hern’s piece. It has frequently been asked about baseball’s most famous poem, Franklin Pierce Adams’s “Baseball’s Sad Lexicon,” which contained the immortal, “Tinker to Evers to Chance” phrase, generating the vision of an efficient double-play combination. Like Hern, Adams’s poem reflected an image, his of Chicago Cubs infielders Joe Tinker, Johnny Evers, and Frank Chance’s defensive abilities.

Over the years, Adams’s work has been critiqued as to accuracy, primarily because his stanza is often credited with their being elected to the Hall of Fame in 1946.1 While analysis will doubtless continue, there is no argument that they were significant cogs on a team that won four pennants and two World Series within five years.

Thus, how important were Spahn and Sain in the Braves winning the pennant in 1948? Virtually any reference to the 1948 Braves mentions their contributions.

Sain (24-15) and Spahn’s (15-12) combined 39-27 contributed largely to the Braves’ 91 wins that year, but their joint effort was hardly unique that season. Cleveland’s Gene Bearden and Bob Lemon teamed to go 40-21, while Yankees pitchers Vic Raschi and Ed Lopat posted a 36-19 mark. The fifth-place Giants’ Larry Jansen and Sheldon Jones’s 36-20 record compared favorably to the Bostonians. Given their record in 1948, while solid, it was not unique. What caused Spahn and Sain’s effort to gain lasting resonance?

First, of course, is that the Braves won the pennant — the Yankees and Giants didn’t. Second is the alliterative nature of Spahn and Sain’s names. Bearden and Lemon, or Raschi and Lopat, would challenge the best of poetic talent. Jansen and Jones suggest rhythmic potential, but the Giants’ fifth-place finish made any lyrical endeavor inconsequential. Third, Hern’s piece captured a crucial time in the pennant race during which his description was decidedly on the mark. A combination of unique events came together to make it so.

Early in September, Boston was in a tight pennant race with Brooklyn. On the morning of September 6, Boston held a slight two-game lead. While Sain, Spahn, and rookie Vern Bickford were pitching well, the fourth man in the rotation, Bill Voiselle, wasn’t. After developing a 10-6 record through early July, he fell off, losing seven of his next 10 decisions. Voiselle’s loss to the Phils on September 4 was his third in a row.

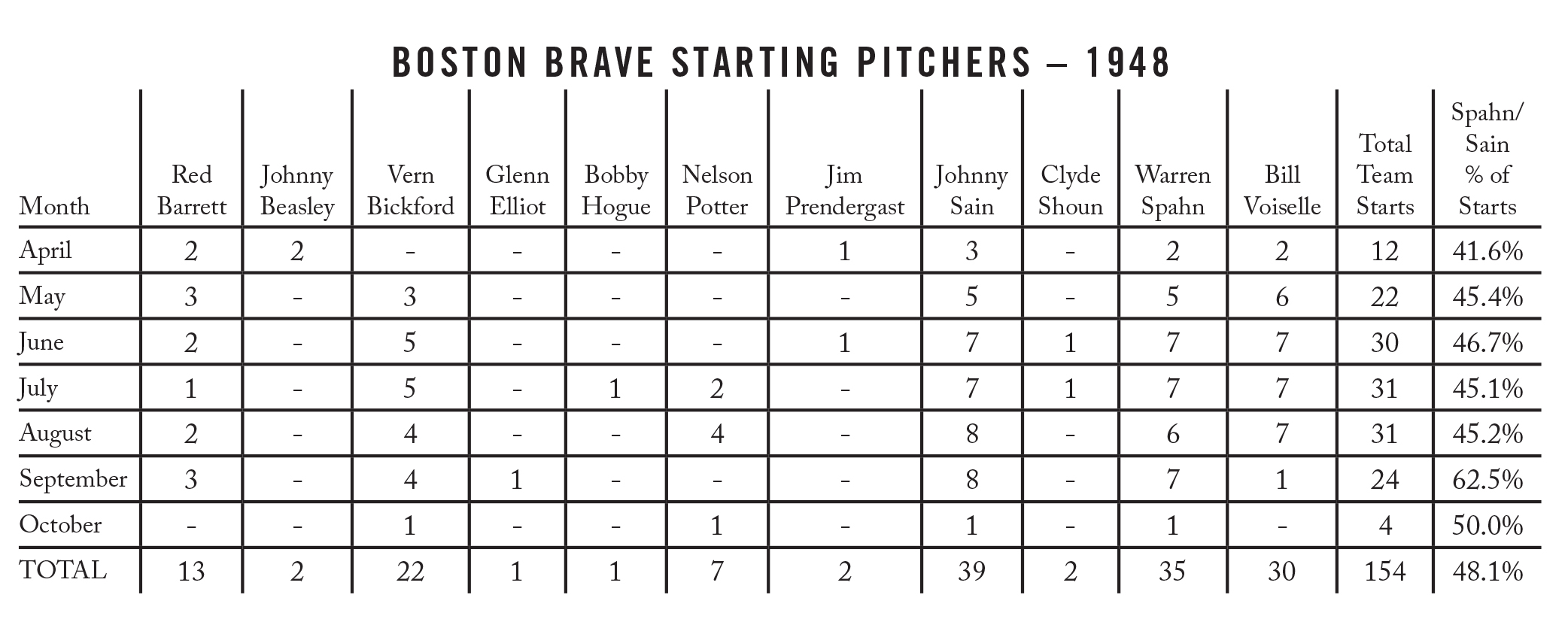

With that defeat, manager Billy Southworth took Voiselle out of the rotation essentially augmenting Spahn and Sain’s starts by giving them Voiselle’s.2 In August Sain, Spahn, and Voiselle had each started seven of the 31 games Boston played that month. In September, of the 24 games played, Sain started eight, Spahn seven, and Voiselle just that one game in early September before being pulled from the rotation.

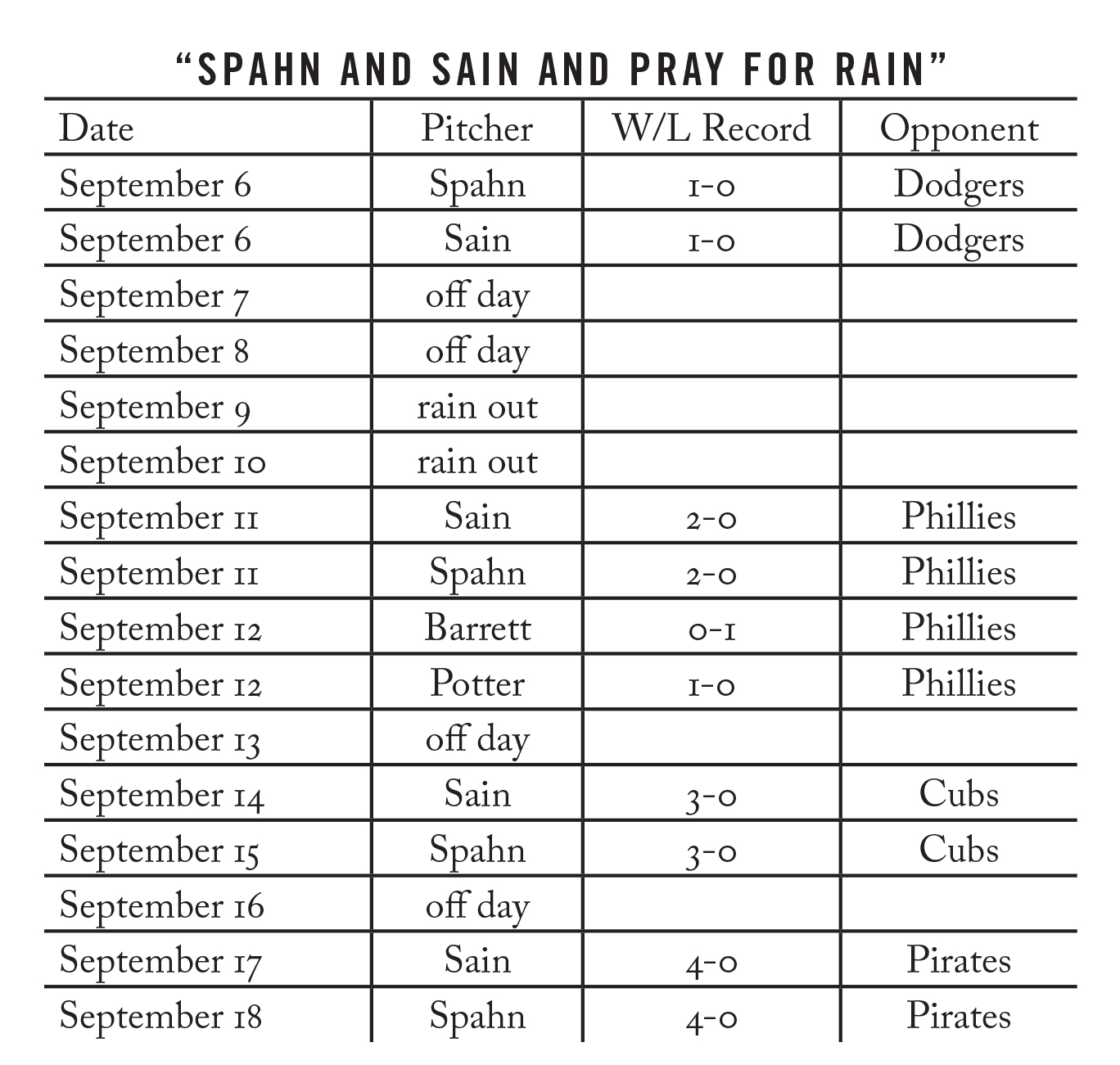

On September 6 Spahn and Sain threw complete-game victories against the Dodgers in a doubleheader. Two off days and two rainouts brought them into a doubleheader against the Phils on the 11th. Bickford had been scheduled to pitch in the rained-out game of the 9th, but Southworth elected to go with Sain and Spahn, who again supplied complete-game wins. The next day Red Barrett and Bickford pitched, splitting a second consecutive doubleheader with Philadelphia. The 13th was an offday; Southworth came back with Sain on the 14th and Spahn on the 15th against Chicago. Two more complete-game victories. An offday on the 16th, then Sain and Spahn against Pittsburgh. Again, two complete-game wins. During a 13-day stretch, Boston had gone 9-1. Sain and Spahn won four games apiece, each a complete-game effort. At that point Boston’s lead over Brooklyn had grown to six games with two weeks left to play. From then on, Bickford was back in the rotation. On September 26, Boston clinched the pennant.

Sain’s 24 wins topped the majors, but Spahn’s15-12 record was just above average, certainly below his 21-10 performance in 1947. Over the years efforts have been made to analyze their combined deeds before, during, and after the 1948 season. One article offered, “The implication (Hern’s poem) is that for a period of several years after World War II, Hall of Famer Warren Spahn and 4-time 20-game winner Johnny Sain were the only good pitchers on the Boston Braves.”3Valid points, but Hern was not writing about past seasons, other contributors or the 1948 season. He had a specific point of view. As did Adams on Tinker, Evers, and Chance. Adams’s stanza contained the phrase, “Ruthlessly pricking our gonfalon bubble.”

His mention of a gonfalon, or banner, alluded to the National League pennant. Adams’s poem first appeared in July 1910 when the Cubs and Giants were fighting for first place. The Giants, a close second behind Chicago, should not have given cause for the overall gloominess Adams’s poem projected. His outlook was not driven by a particular game but by the fact that Chicago’s dynastic run had consistently thwarted the Giants’ hopes. It was out of that setting, not a capacity for double plays, that Adams created his work.

The reverse was true of Hern. While what Spahn and Sain did during previous years, as well as the efforts of others, had pertinence, his focus was on two individuals carrying the day for Boston.4Their exploits are still recalled because of Hern’s self-described “ode,” which Sain years later said was inspired by Southworth. Soon after Sain and Spahn threw their second set of wins, Southworth described his revised pitching rotation to reporters as “Spahn on one day, Sain the next.” 5That comment gave impetus to Hern’s poem, published the next day.

Both pitchers appreciated that it kept them forever in the minds of fans.” It’s not so much my pitching people know, but that little poem about me and Johnny Sain with the forty-eight Braves. We got it [the jingle] because it rhymed,”Spahn mused years later. While he appreciated being remembered, he did not like the phrase because it failed to account for the efforts of others — “… guys like Vern Bickford… and Nelson Potter… had good years and they’re not remembered.6 Sain pointed out that theirs was an intense burst of effort. He recalled tiring late in games, indicating this sustained level of performance could not be continued. Sain felt a degree of reluctance as to its popularity– “Unfortunately, that diminishes the contributions of our other starters that year” — recalling Voiselle’s and Bickford’s roles.7 Voiselle, when asked years later if he resented being overlooked, agreed: “I reckon I was, in a way. We had some pretty good pitchers on that team — Spahn, Sain, Vern Bickford. Nelson Potter did real good that year and so did Red Barrett.”8

Spahn, Sain, and others who later commented were right; the poem did take away from the efforts of Bickford, Voiselle, and the rest of the pitching staff. But Hern, almost certainly unaware of how this stanza would carry over time, was not concerned with anything but the situation facing the Braves in September 1948.

Hern’s original prose is at variance with today’s familiar phrasing. His original lines:

“Back will come Spahn, followed by Sain,

And followed, we hope, by two days of rain”

have of course, given way to:

“Spahn and Sain and pray for rain,”

Or

“Spahn and Sain and two days of rain.”

Various references vaguely explain the transformation in wording. The poem “was eventually shortened conversationally” as described in a biography of Billy Southworth.9 Jim Kaplan’s book The Greatest Game Ever Pitched notes that “the poem was shortened popularly” to its present form.10 On the Internet, Spahn’s entry at Wikipedia relates that “popular media eventually condensed” to today’s phrasing.11

“Eventually” seemed quick; three weeks after Hern’s poem appeared, Whitney Martin, writing for the Washington Post about the ensuing World Series between Boston and Cleveland, observed, “The slogan up here in the cod country during the Boston Braves’ regular season was “Spahn and Sain and two days of rain.”12 As early as this recognizable verse is, it has to stand behind Hern himself. His verse came in an article titled “Braves Boast Two-Man Staff.” The subheading in part was “Pitch Spahn and Sain, Then Pray for Rain.” Thus Hern not only came up with a poem about Spahn and Sain but with the phrase that immortalized them.

GREG ERION is retired from the railroad industry and currently teaches history part-time at Skyline Community College in San Bruno, California. He has written several biographies for SABR’s BioProject and is currently working on a book about the 1959 season. Greg is one of the leaders of SABR’s Baseball Games Project. He and his wife Barbara live in South San Francisco, California.

Warren Spahn and Johnny Sain down the stretch in 1948

1948 Boston Braves starting pitchers

(Click images to enlarge)

Notes

1 See for instance, Rob Neyer and Eddie Epstein, Baseball Dynasties: Greatest Teams of All Times (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2000), 35-40.

2 Saul Wisnia, “Bill Voiselle,” SABR BioProject, sabr.org/bioproj/person/230d3efb.

3 baseballevolution.com/keith/sainrain.html.

4 Roger Birtwell, “Red-Hot Sain Heats the Beans for Boston,” The Sporting News, September 29, 1948, 6.

5 Gerry Hern, “Braves Boast Two-Man Staff,” Boston Post, September 14, 1948.

6 baseball-almanac.com/poetry/po_rain.shtml; Jim Kaplan, The Greatest Game Ever Pitched, Juan Marichal, Warren Spahn and the Pitching Duel of the Century (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2011), 68.

7 Danny Peary, ed., We Played the Game: 65 Players Remember Baseball’s Greatest Era, 1947-1964 (New York: Hyperion, 1994) 59.

8 John C. Skipper, Billy Southworth: A Biography of the Hall of Fame Manager and Ballplayer (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2013), 160.

9 Skipper, 159.

10 Kaplan, 68.

11 wikipedia.org/wiki/Warren_Spahn#.22Pray_for_rain.

12 Whitney Martin, “‘Sain, Rain, Back With Sain’ Lone Series Hope for Braves,” Washington Post, October 8, 1948, B4.