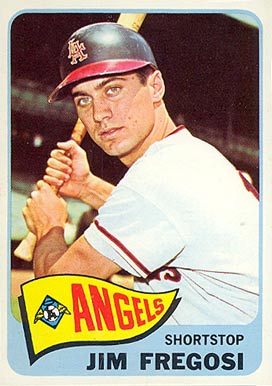

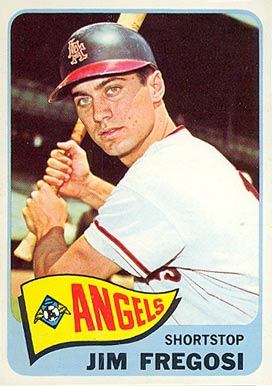

Jim Fregosi

Most famous today for being on the wrong end of one of history’s most lopsided trades, Jim Fregosi was a six-time All-Star who drew comparisons with the finest players in the game at a young age. But an 18-year major league playing career, coupled with 15 years as a big league manager, are enough evidence that Fregosi deserves to be remembered for more than being traded for Nolan Ryan.

Most famous today for being on the wrong end of one of history’s most lopsided trades, Jim Fregosi was a six-time All-Star who drew comparisons with the finest players in the game at a young age. But an 18-year major league playing career, coupled with 15 years as a big league manager, are enough evidence that Fregosi deserves to be remembered for more than being traded for Nolan Ryan.

James Louis Fregosi was born on April 4, 1942 in San Francisco, California. His parents, Archie and Margaret, owned and operated a grocery, and the family (including Jim’s older brother and older sister), lived comfortably in San Mateo. “The first thing I remember,” Jim recalled early in his career, “is standing on a basket putting groceries in a paper bag. All my life, my dad has been getting up at four in the morning and working until six at night.” Besides working for his father, Jim later toiled as a busboy in a local restaurant.1

During the day, he played every sport he could and became a great local athlete. Jim’s dad, a former semi-pro baseball player, sponsored and coached Jim’s youth ball team, the Fregosi Market nine, and snuck away from work to see his other teams when he could. At Serra High School Jim won 11 varsity letters, earning All-League honors in football, basketball and baseball, and also running sprints and jumping for the track team. In 1959 he was named the Peninsula Athlete of the Year.2

Fregosi had his choice from among many college football scholarship offers and baseball contracts, but just before his college year would have started he signed with Boston Red Sox scout Charley Wallgren for a $20,000 bonus. He honed his baseball skills that offseason by playing in the Peninsula Winter League, a fall/winter circuit composed mostly of professional players who played on the San Francisco peninsula. In the spring of 1960 Red Sox sent Fregosi to their Alpine, Texas club in the Class-D Sophomore League. Alpine was a long way from Boston, literally and figuratively, but the 18-year old Fregosi hit .265, fielded well at shortstop, and made the league’s All-Star team.

After the 1960 season, the eight American League teams held an expansion draft to stock new teams in Los Angeles and Washington. Figuring that their 18-year-old in Alpine was nowhere near ready for the majors, the Red Sox did not protect Fregosi from the draft. In the meantime, their prospect was again playing with San Mateo, and drew the attention of Bill Rigney, the manager of the new Los Angeles club.. Rigney liked what he saw and convinced the Angels to select Fregosi with the 35th pick, the fifth player taken from the Red Sox.

The Angels started their new property with Dallas-Ft. Worth in the Triple-A American Association, a huge promotion, and Fregosi responded by hitting a respectable .254 with six home runs, but also made 53 errors at shortstop. The Angels brought him to the big leagues in September, and he went 6-for-27 in his brief trial.

After suggesting that the 19-year-old Fregosi could win the starting major league shortstop job in 1962, the Angels ended up sending him back to Dallas-Ft. Worth. Fregosi sulked at his demotion, but hit .283 in 64 games and returned to the Angels in late June. The 20-year-old struggled for a few weeks, but by mid-August he had claimed the starting job. After flirting with a .300 average a few times, he ended the year at .291 with three home runs. His first round tripper came on September 10, at Minnesota’s Metropolitan Stadium, off the Twins’ Dick Stigman. Nine days later he hit the first ever inside-the-park home run at Dodger Stadium, which the Angels shared with the LA Dodgers.

Fregosi started his career at about 6-feet and 175 pounds, but he was 6-2, 195 within a few years. With his size came strength and more power. In his first full season, the 21-year-old hit .287 with nine home runs, 12 triples, and 29 doubles. This was in the middle of a very difficult time for hitters, and Fregosi was playing in the pitcher-friendly Dodger Stadium; he hit .315 with six home runs in his road games. “It is absolutely amazing the way Fregosi has improved week to week,” raved Rigney near the end of the season.3

In 1964 Fregosi had a breakout season and became a recognized star. In 147 games, he hit .277 with 18 home runs and 9 triples. These were excellent number in the 1960s, especially for a middle infielder in a pitcher’s park. He was selected (by his fellow players) to start the All-Star game, held that year at New York’s Shea Stadium. As the game’s leadoff batter, he singled off the Dodgers’ Don Drysdale, and went on to play the entire game. On July 28 he hit for the cycle, backing Dean Chance’s two-hitter and 3-1 victory over the Yankees.

“The kid is one of those exceptional athletes who has everything going for him,” said Rigney. “He has speed, size, strength, desire and intelligence. He can be the best. It’s all up to him.”4 He had come far already, thought Detroit star Al Kaline, who called him “the best shortstop in baseball.” Ernie Banks, former star shortstop for the Cubs, now a first baseman, said, “he’s one of the few who might be able to hit .400 some year.”5 Playing for a team out of contention, it took a bit longer for the general public to catch on. “If Jim Fregosi played for the Los Angeles Dodgers instead of the Los Angeles Angels,” thought one writer, “the city would cast his footprint or his gloveprint or something in cement outside of Grauman’s Chinese Theatre.”6

Fregosi had married Janet, his high school sweetheart, in 1961 and James Jr. came along in 1964. Off the field, Fregosi and three teammates built a 33-unit apartment building in Inglewood, where the Fregosis lived while also acting as rental agents. The California couple, who both drew attention for their good looks, appeared to have it all. “I think we have been lucky so far, I admit it,” said Fregosi.7

Fregosi continued to star in 1965, hitting .277 with 15 home runs and 64 RBI. He was the rare middle infielder who batted third on his team, and led the club in homers and RBI. The season also marked the Angels’ final year as tenants in Dodger Stadium, and the first year known as the California Angels. “You don’t see me crying that we’re leaving this place,” said Fregosi.8 In his first year in the new Anaheim Stadium, which would prove to be an equally good park for pitchers, Fregosi’s average dropped to .252 and he hit just 13 home runs. He did return to the All-Star game, playing the final five innings of the AL’s 2-1 ten-inning loss at St. Louis’s Busch Stadium. Although his $40,000 annual salary was the highest among all shortstops in the AL, there was talk after the season that he might be in line for a decrease. Fregosi disagreed. “I won’t accept a cut because I don’t believe the Angels would trade me for any other shortstop in baseball.”9

Fregosi blamed some of his 1966 troubles to a battle with his weight—he reported to camp at 210 pounds, and lost 20 over the course of the season. He came to camp in 1967 at 190, and also gave up golf and had a strict exercise program in the off-season. He was the leader of the team, both on and off the field, and he vowed to have his best year. In the end he got his average up to .290, and added 38 extra base hits. The All-Star game was in Anaheim that year, and Jim ended up playing the final 12 innings of the AL’s 15-inning 2-1 loss, going 1-for-4. He was also named to the AL’s post-season All-Star team by The Sporting News. Fregosi won his first Gold Glove award, as did his second base teammate Bobby Knoop. The pair drew raves as the best double play combination in the league. In December Fregosi visited military hospitals in the Far East, visiting men who had been wounded in Vietnam. It was a numbing experience for the ballplayer, who admitted that he had not given the war much thought previously.

Fregosi continued to receive accolades around the game. In the spring of 1968, former star infielder Al Rosen suggested that the 25-year-old Fregosi “may be one of the best players this game has ever produced. I don’t believe I’ve ever seen a shortstop who can do as much as Fregosi.”10 Fregosi’s averaged dipped to .244 in 1968, a year when the AL hit .230. He led the league with 13 triples, and on May 20 hit for the cycle for the second time in his career, this time against the Red Sox. Fregosi batted six times in all, mixing in a groundout and an intentional walk, and won the game with a game-ending single in the bottom of the 11th inning. He also started the All-Star game, and led off the contest in Houston with a double off Don Drysdale. The AL went down to a 1-0 defeat.

He played in the All-Star game again in 1969, his fifth, capping a year in which he hit .260 with 12 home runs, and played solid defense despite battling a sore knee. He had an excellent season at the plate in 1970, batting .278 with a career-high 22 home runs. With the Angels in their first pennant race in many years, Fregosi began to get support as the league’s MVP. “If we win this race,” said manager Lefty Phillips, or even if we finish close up in second, “[he] has to be the league’s most valuable player.”11 The Angels ultimately faded to third, and Fregosi ended up 12th in the end-of-the-year balloting.

After the 1970 season, Gene Autry told a reporter that he’d like to see Jim Fregosi become player-manager someday. This was a surprise to Lefty Phillips, who was a Manager of the Year candidate, but Autry added, “I don’t mean it will happen next year, but I do think it would be good for baseball.”12 Fregosi had enormous respect everywhere in baseball, and certainly from everyone associated with the Angels team.

The next season, 1971, would turn into a very difficult year for the Angels and for Fregosi. The team was beset with huge player controversies, notably one involving outfielder Alex Johnson, whose demeanor and lack of hustle drew repeated fines and suspensions before he was finally shut down for the year in June. Tony Conigliaro, acquired in a big trade with the Red Sox in the off-season, struggled for a few months before his own physical and mental breakdown led to his retirement, at age 26, in July. The Angels had expected to contend for the AL West title, but the various dramas turned the season into a nightmare for Phillips and most of the team. Fregosi, the team’s leader, hit just .233 with five home runs.

Near the end of the year Fregosi was moved to left field, a sign that that 28-year-old body could no longer stand up to the rigors of the middle infield for 160 games. In October it was widely reported that Fregosi would be offered the manager’s job. Instead, on December 10, his 10th wedding anniversary, he was traded to New York Mets for four players: pitchers Nolan Ryan and Don Rose, outfielder Leroy Stanton, and catcher Francisco Estrada. Ryan, a 25-year-old pitcher who had yet to harness his obvious fireballing talents, was the key player, the other three were minor leaguers. Fregosi was delighted with the deal, though the Angels fans were not.

The Mets acquired Fregosi to play third base, but he hurt his thumb in the spring and struggled with his changed circumstances. “It’s hard to adjust to a new position,” he admitted, “and when you change leagues there is a whole new set of ball parks and pitchers to contend with. After you’ve been in one league for 10 seasons you know the pitchers as well as you are going to get to know them. Here I have to learn two or three new things in every game.”13 In the end he had a very disappointing season, batting .232 with five home runs, while Ryan enjoyed the first of many outstanding seasons in his career. The trade would go down as one of the worst in baseball history.

With all of his necessary adjustments, Fregosi later admitted that he did not help matters by playing out of shape in 1972. “I was leading the good life and I loved it. But I was paying for it on the field.” He showed up in good shape the next year, having not had a drink in four months, vowing to get out of the game if he could not bounce back from his two off years.14 In any event, he hit no better for the Mets in 1973, just .234 in 45 games, before they decided to cut bait in July and sold his contract to the Texas Rangers. He did better there, .268 with six homers in 173 at bats, but his days as a star were clearly behind him now. Just 31 years old, he had put together three mediocre seasons in a succession.

Fregosi ended up playing four years with the Rangers, getting time at third base, first base and designated hitter. His best year was 1974 when he hit .261 with 12 home runs in 253 at bats, but he played less and less after that. In June 1977 he was traded to the Pirates for former teammate Ed Kirpatrick, and Fregosi played the rest of that season and part of the next as a pinch-hitter and backup corner infielder. He drew his release on June 1, 1978.

His release came at the request of Gene Autry, still running the Angels. California had been in first place on May 26, but lost their next five, including a 17-2 shellacking on May 31. Autry decided to fire manager Dave Garcia, and he wanted Fregosi to replace him. “Garcia was a dandy guy, but he was too quiet,” Autry said. “Jimmy is a scrapper, a go-getter. I felt he would be someone the players would respect.” 15 He contacted the Pirates, who agreed to release their player. Fregosi played his last game for the Pirates on May 31, and two days later managed the Angels in Anaheim against the Red Sox.

Fregosi was 36 years old, and he took over a team filled with veteran stars—Don Baylor, Bobby Grich, Joe Rudi. His best pitcher was Nolan Ryan, who would always be linked with Fregosi in people’s minds. Fregosi was not afraid to make moves, in particular installing Brian Downing as full-time catcher rather than splitting time with Terry Humphrey, a superior defensive catcher who did not hit. Ryan and Frank Tanana loved working with Humphrey, who had therefore received most of the playing time. “When I first made the change,” said Fregosi, “Tanana came into my office and said, ‘Humphrey catches me,’ and I told him, ‘Not anymore.’”16 The team finished 87-75 in a season tragically marred by the late-season death of outfielder Lyman Bostock, murdered in a case of mistaken identity.

In 1979, Fregosi’s first full year as manager, the Angels won 88 games and took the AL West crown. The team had picked up Rod Carew in the off-season, and was led by the big hitting of Carew, Baylor, Grich and Downing, and the pitching of Ryan and Dave Frost. This marked Fregosi’s first experience with the postseason, but his club lost the ALCS to the Orioles three games to one.

In the offseason Ryan signed with the Houston Astros as a free agent, contributing to the Angels 1980 collapse to sixth place with just 65 wins. In the offseason Autry reloaded again, adding All-Stars Fred Lynn, Rick Burleson, and Ken Forsch to the cause. But when the 1981 team began the season 22-25, Fregosi was fired in late May, and replaced by Gene Mauch. Looking back years later, Fregosi conceded that he might have been too hard on some of his charges. “I expected too much from the players,” he said.17

Fregosi next took a year off from the game before he was hired in 1983 to manage the Louisville Redbirds, the St. Louis Cardinal affiliate in the American Association. Although Louisville was the minor leagues, it was the very top of the minor leagues. The 1982 team had set the all-time minor league attendance record, with over 800,000 fans. In Fregosi’s first year the Redbirds went over a million fans and finished first in the league before losing in the playoffs. Still under Fregosi, the Redbirds came back and won the league championship the next two seasons. “I’m having one of the most enjoyable years I’ve ever had in baseball,” said Fregosi early in his tenure there. 18 During his three-and-half years in Louisville, Fregosi managed such players as Andy Van Slyke, Danny Cox, Todd Worrell, Vince Coleman, Terry Pendleton, and Jose Oquendo, all of whom would go on to star for World Series teams with the Cardinals.

It is likely that Fregosi had several opportunities to return to the major leagues during his years in Louisville. He finally accepted a job in June 1986 when he took over the Chicago White Sox, replacing Tony LaRussa (Doug Rader managed two games on an interim basis). The White Sox (27-39 at the time) were led by catcher Carlton Fisk, outfielder Harold Baines, and pitchers Floyd Bannister and Richard Dotson. Many of these players had off years in 1986, and played only slightly better under Fregosi (45-51).

The White Sox of the late 1980s played with a bit of a cloud over their heads, as the owners were considering a move to the Suncoast Dome in St. Petersburg, Florida while trying to get a commitment on a new stadium in Chicago. The team finished 12th and 13th (out of 14) in league attendance in 1987 and 1988, with teams that were not close to contending (77 and 71 wins). The 1987 club was led by three 200-inning starting pitchers—Dotson, Bannister, and Jose DeLeon—all of whom were traded in the following offseason, moves that caused Fregosi to clash with GM Larry Himes.19 Rookie right-handers Jack McDowell and Melido Perez pitched well but could not compensate for the losses. At the end of the 1988 season, Fregosi was fired after two-and-half years in Chicago.

Fregosi was out of the majors for two years this time, and took his next job with the 1991 Philadelphia Phillies. The Phillies had not contended since their 1983 pennant, and had won 65, 67, and 77 games over the previous three years. When they began the 1991 season 4-9 under Nick Leyva, the Phillies made a change and brought in Fregosi. The Phillies were not ready to contend, but they wereassembling a team that could, with such stars as catcher Darren Daulton, first baseman John Kruk, and center fielder Lenny Dykstra. Over the next couple of years, the Phillies added third baseman Dave Hollins, pitchers Curt Schilling and Mitch Williams, and several other useful players, creating a wild, crazy, and talented bunch. The team won just 78 games in 1991, then 70 the next year, before breaking through to win 97 games and the NL East in 1993. The symbol of the team might have been Dykstra, the league’s best leadoff hitter, who lived life and played the game with reckless abandon.

“The actual pilot of these Phillies,” said one writer, “is 51-year-old Jim Fregosi, who deserves credit for not restraining the Phillies’ diverse personalities and thus for not restraining their play on the field.”20 Fregosi was no longer the firebrand he had been in his earlier managerial days. “I’m more patient with the players now,” Fregosi said. “Much more patient.” Outfielder Pete Incaviglia said, “”If you can’t play for Jimmy, you can’t play for anybody.”21

After holding off the Montreal Expos to win the division, the Phillies met the Atlanta Braves, two-time defending league champs, in the NLCS. After losing two of the first three games, the Phillies stormed back to win three straight to capture the pennant. The Phillies then lost the World Series in six games, the finale on Joe Carter’s game-ending home run off Mitch Williams in the bottom of the ninth inning. Fregosi’s most controversial decision was his choice to stick with Williams, who had already blown two saves in the NLCS (both times he ended up getting the victory when his team came back) and blown a five-run lead in Game Four of the World Series. When he came in to hold a two-run lead in Game Six, many felt that he was emotionally unfit to be placed in that position. After the game, Fregosi said he never hesitated to go with his closer. “As I told Mitch after the game, he’s the one who got us here,” said the skipper. “He had 40-some saves. He’s the guy. Unfortunately, he didn’t get the job done.”22 After the season Fregosi finished second in the balloting for manager of the year, trailing Giants manager Dusty Baker.

The 1993 Phillies would turn out to be a one-year wonder—this was the only Phillies team of he decade to finish over .500. They were 54-61 and well back in fourth place when the strike hit in 1994, then finished 21 games out behind Atlanta in 1995. After bottoming out in 1996 (69 wins, and last place), Fregosi was fired after the season.

Fregosi’s next gig was working for the San Francisco Giants as an assistant to general manager Brian Sabean. This lasted two years, until he was hired to manage the Toronto Blue Jays in 1999. Previous manager Tim Johnson had gotten in trouble for a series of fabrications about his supposed service in Vietnam and college football exploits. When the ensuing controversy dragged on and threatened to dominate the atmosphere around the team, Toronto fired him in the middle of spring training, handing Fregosi the reins without an off-season to prepare. After having been a young peppy manager in the late 1970s, he was now the old school tough baseball man. “There are a lot of young, not overly outgoing people here who grew in this organization together,” he says. “I’ll go to bat for them.”23

Fregosi guided the Blue Jays to two third place finishes—84 and 83 victories—before being fired for the fourth time. “We had a good two years. Toronto is a great city and was a lot of fun,” Fregosi said.24

In the ensuing years Fregosi has been a special assistant to Atlanta Braves general managers John Schuerholz and then Frank Wren, working as the club’s top advance scout. He interviewed for at least three managerial jobs in the decade after his Blue Jays gig—with the Giants after the 2002 season (when they ultimately hired Felipe Alou), the Phillies after the 2004 season (losing out to Charlie Manuel), and the Dodgers after 2005 (Grady Little).

Fregosi marriage to Janet ended soon after his playing career. The couple had two children: Jim Jr., who had a five-year minor league career, and Jennifer. While he managed in Louisville he met Joni, and the couple married in 1986 during his first summer in Chicago. Jim and Joni settled in Florida, and raised three children there–Nicole, Robert, and Lexi.

Fregosi has received many honors during his retirement years. In 1988 the Angels retired Fregosi’s uniform number 11, and the next year he became the second player in the team’s Hall of Fame (following Bobby Grich). He was later inducted into the National Italian American Sports Hall of Fame. In 2010 the Professional Baseball Scouts Foundation presented Fregosi with the George Genovese Award for excellence in scouting.

Over a baseball career spanning five full decades Fregosi has excelled as a player, manager, and scout, earning respect at every step of his long journey in the game. He might be the answer to a baseball trivia question to many, but Jim Fregosi’s reputation, and his place in the history of the game, is secure.

Jim Fregosi died early in the morning on Friday, February 14, 2014, after reportedly suffering a stroke while on a cruise with baseball alumni.

Notes

1 Bill Libby, “Jim Fregosi’s Fun,” Sport. September 1964, 58.

2 Libby, “Jim Fregosi’s Fun.”

3 Braven Dyer, “Hats Off!” The Sporting News, September 21, 1963, 23.

4 Braven Dyer, “Hats Off!” The Sporting News, May 30, 1964, 26.

5 Libby, “Jim Fregosi’s Fun.”

6 Frank Deford, “A Star On The Wrong Team,” Sports Illustrated, June 1, 1964.

7 Libby, “Jim Fregosi’s Fun.”

8 Mark Mulvoy, “Baseball’s Week,” Sports Illustrated, October 4, 1965.

9 Ross Newhan, “Top-Salaried Fregosi Nips Talk of Slash,” The Sporting News, October 1, 1966, 9.

10 Ross Newhan, “Rosen in Rhapsody Over Fregosi,” The Sporting News, March 30, 1968, 24.

11 Ross Newhan, “Angel Fregosi Chant Grows Louder,” The Sporting News, August 8, 1970, 17.

12 Ross Newhan, “Autry Mentions Fregosi May Manage Angels,” The Sporting News, September 4, 1970, 10.

13 William Leggett, “How Sweet It Is!” Sports Illustrated, May 22, 1972.

14 Jack Lang, “Fregosi, Minus Middle Tire, Motors Merrily as Met,” The Sporting News, March 24, 1973, 48.

15 Larry Keith, “So Halo, Everybody, Halo,” Sports Illustrated, August 28, 1978.

16 Keith, “So Halo, Everybody, Halo.”

17 Sam Carchidi, “A Manager Who’s Come A Long Way,” Philadelphia Enquirer, October 6, 1993.

18 William F. Reed, “Louisville Is A Major Minor,” Sports Illustrated, July 11, 1983.

19 Peter Gammons, “Baseball,” Sports Illustrated, April 18, 1988.

20 Tim Kurkjian, “A Flying Start,” Sports Illustrated, May 10, 1993.

21 Carchidi, “A Manager Who’s Come A Long Way.”

22 Michael Sokolove, “Remaining With Mulholland Was The First Tough Call,” Philadelphia Enquirer, October 24, 1993.

23 Stephen Cannella and Jeff Pearlman, “Appier of Their Eyes,” Sports Illustrated, April 19, 199.

24 Inquirer staff, “Blue Jays Fire Fregosi,” Philadelphia Enquirer, October 11, 2000.

Full Name

James Louis Fregosi

Born

April 4, 1942 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

Died

February 14, 2014 at Miami, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.