Barney Pelty

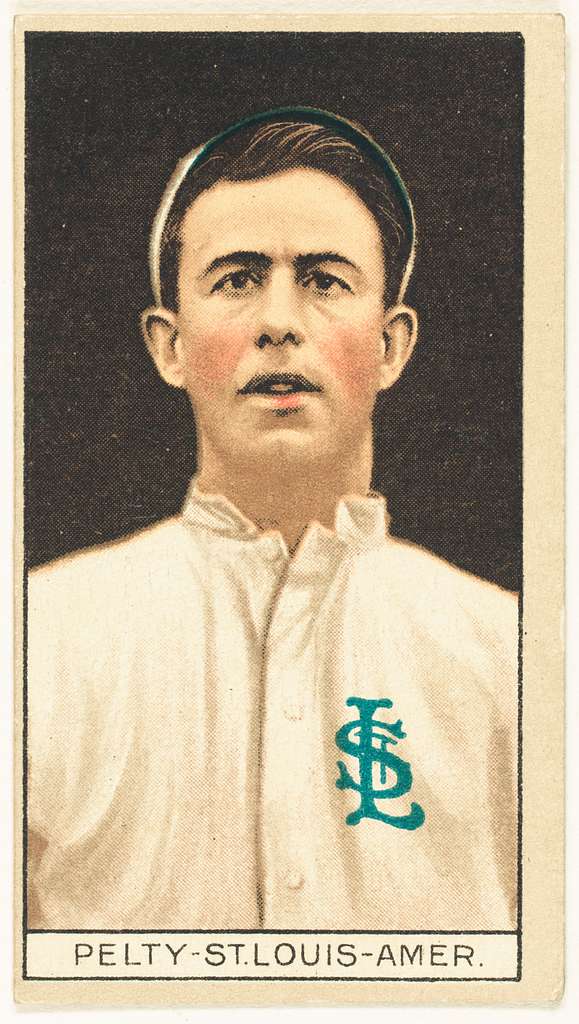

Starting 217 games as a Browns pitcher and relieving in 49 more, Barney Pelty was, along with shortstop Bobby Wallace, the common thread on a team that flirted with destiny and fell into oblivion. Armed with an excellent curveball that kept opposing hitters off-balance, the 5’9″, 175-lb right-hander recorded 22 career shutouts, but also was shut out 32 times, meaning that fully a quarter of his decisions ended as a shutout, one way or the other. In his best season, 1906, Pelty finished with a 1.59 ERA, which still stands as a record for the lowest single season ERA in Browns/Orioles franchise history, and a league-best .202 opponents batting average, but still won only 16 games. A man of cautious intelligence, with handsomely broad features and prominent ears that made him seem slightly older than he was, Pelty was often used by his managers as a field coach, and after his baseball career dabbled in trade and politics. One of only a handful of Jewish ballplayers during the Deadball Era, “the Yiddish Curver” made no attempt to hide his heritage, but was also not a religious person. If he faced anti-Semitism, he certainly never complained publicly or let it be known that it bothered him. He was a proud man who dealt with life the way he dealt with the hard-luck team he played for, with a quiet and dignified professionalism.

Starting 217 games as a Browns pitcher and relieving in 49 more, Barney Pelty was, along with shortstop Bobby Wallace, the common thread on a team that flirted with destiny and fell into oblivion. Armed with an excellent curveball that kept opposing hitters off-balance, the 5’9″, 175-lb right-hander recorded 22 career shutouts, but also was shut out 32 times, meaning that fully a quarter of his decisions ended as a shutout, one way or the other. In his best season, 1906, Pelty finished with a 1.59 ERA, which still stands as a record for the lowest single season ERA in Browns/Orioles franchise history, and a league-best .202 opponents batting average, but still won only 16 games. A man of cautious intelligence, with handsomely broad features and prominent ears that made him seem slightly older than he was, Pelty was often used by his managers as a field coach, and after his baseball career dabbled in trade and politics. One of only a handful of Jewish ballplayers during the Deadball Era, “the Yiddish Curver” made no attempt to hide his heritage, but was also not a religious person. If he faced anti-Semitism, he certainly never complained publicly or let it be known that it bothered him. He was a proud man who dealt with life the way he dealt with the hard-luck team he played for, with a quiet and dignified professionalism.

Barney Pelty (not Peltheimer, as is often reported) was born in Farmington, Missouri, on September 10, 1880, the youngest of six children of Samuel and Helena Pelty. Samuel, a Prussian Jew, had immigrated to the United States at age seventeen to avoid conscription into the Prussian Army. He arrived in St. Louis, married Helena (who was also Jewish), and pursued a career as a cigar maker.

Barney was an athletic boy who grew up playing football and baseball and served as shortstop for the “Little Potatoes” children’s baseball team in Farmington. According to his parents, he was a born pitcher, always wanting to “throw things” as a toddler. His baseball talent began to manifest itself in grammar school, and he received a scholarship to pitch for the varsity team at Carleton College, which was located in Farmington until its closure in 1916. Although he left to play for Blees Military Academy in Macon, Missouri two years later, Carleton is where he met Eva Warsing who would later be his wife. He pitched for Blees Military Academy for the 1899 and 1900 seasons. His first offer from organized baseball came from Nashville of the Southern Association in 1902, but he injured his arm in practice. He wound up playing for Nashville that season as a catcher. Unhappy in this new role, he quit the team and went home.

After his arm recovered, he joined a semi-pro team in Cairo, Illinois, again as a pitcher, and finished out the 1902 season there. In 1903, he signed to play for the Cedar Rapids Rabbits in the Three-I League. Both the Red Sox and Browns scouted and tried to acquire him over the course of the summer. Unfortunately for Pelty, the Browns won the contest, purchasing his contract from Cedar Rapids in August. Pelty made his major league debut on August 20, 1903, in relief against New York and two days later started and won 2-1 against Bill Dinneen and the Boston Red Sox, who were on their way to the first modern World Series Championship. Starting six games for the Browns in 1903, Pelty proved himself with a 3-3 record and 2.40 ERA. The following season, Pelty became a workhorse for the Browns, hurling 301 innings en route to a 15-18 record and mediocre 2.88 ERA.

At some point, Pelty acquired the nickname the “Yiddish Curver,” and indeed, his curve ball was the most impressive pitch in his repertoire. Newspaper reports of Pelty’s starts frequently indicated that opposing hitters “failed to solve his curves,” even in games which he lost. Pelty was also regarded as a gifted fielder, quick to cover bunts and adept at forcing runners and turning the double play.

In 1905 Pelty finished with a 14-14 record despite pitching for a Browns club which lost 99 games and featured three other pitchers who lost 20 games apiece. Pelty came into his own during the 1906 campaign. On the Fourth of July, Pelty threw a masterpiece, with the help of battery mate Branch Rickey, against the Chicago White Sox. In the first half of a double-header Pelty took a no-hitter into the ninth inning, when shortstop Ben Koehler, who had been brought into the game after the Browns’ crack shortstop Bobby Wallace twisted his ankle, failed to cleanly field a hard shot. The play was scored a hit, and would be the only one Pelty allowed in the Browns’ victory. In 208 major league games, this was also the only game in which Koehler, primarily an outfielder, played shortstop. Throughout the 1906 season Pelty dominated the champion “Hitless Wonders,” shutting them out for 33 consecutive innings before finally allowing his first run of the season to them on Oct. 1, in the 13th inning of a 1-0 loss to Nick Altrock.

Despite that loss, the Browns finished the year above .500 in fifth place, their best showing since 1902. With outfielder George Stone leading the league in batting average, Pelty received better run support than in years past and finished the season with a 16-11 record and career-low 1.59 ERA, second best in the league. No doubt thanks in part to the excellent defense playing behind him, Pelty also allowed the fewest hits per nine innings of any pitcher in the league, despite striking out just 92 batters in 260⅔ innings of work.

Hopes were high for Pelty and the Browns heading into the 1907 campaign, but both Barney and the club fared poorly. The Browns finished the year in sixth place, 14 games under .500, and Pelty fell with them, starting the year 1-7. Though he recovered to finish the year with 12 victories, his 21 losses led the league, and his 2.57 ERA was nearly a full run higher than the mark he had posted the previous year.

In 1908 the Browns reversed their 69-83 mark, finishing in fourth place. Pelty, however, struggled with reduced velocity and a lame arm, throwing just 122 innings for the season while striking out only 36 batters. When he did pitch, he was very good, notching a 7-4 record and 1.99 ERA for the season. Absurdly, the Washington Post complained that “Pelty has never been up to regular work,” a ridiculous statement in light of Pelty’s work over the previous four seasons, when he had tossed an average of 273⅓ innings each year, and performed double-duty as a reliever on numerous occasions.

On April 23, 1909, Pelty bested Cy Young 3-1 on a six-hitter. But with much of the bite gone from his curveball, the sore-armed Pelty required extensive rest between starts to remain effective. In 199⅓ innings of work, Pelty posted an 11-11 record, including five shutouts, to finish the year with a 2.30 ERA. Ominously, Pelty was shut down for the season after making his last start on September 12, and spent the last weeks of the campaign filling in at first, second, shortstop, and right field. Undoubtedly, Pelty was given this opportunity because of his sterling fielding ability. The lifetime .143 hitter batted just .165 for the season.

In 1910 and 1911, Pelty continued to pitch occasionally for the Browns, who were now quickly sinking into the American League cellar. Starting only 41 games over the two seasons, Pelty compiled a lackluster 12-26 record, and for the first time in his career began walking more batters than he struck out. Still showing flashes of brilliance, Pelty tossed three shutouts in 1910 including the first game ever played at Comiskey Park in Chicago, as Pelty outdueled White Sox ace Ed Walsh 2-0 to christen the new grounds on July 1. Pelty finished the 1910 season at 5-11 with a terrible 3.48 ERA for the 47-107, last place Browns. In 1911, the Browns against lost 107 games, but Pelty finished the year with a 7-15 record and 2.83 ERA, the best mark on the club.

Despite optimistic reports out of spring training in 1912, Pelty fared poorly out of the gate for the Browns, dropping five of his six starts. In June he was sold to the Washington Senators for $2,500. Though he pitched well enough for the Senators splitting time between the rotation and the bullpen, Pelty lost four of five decisions and in August was sold to the Baltimore Orioles of the International League. Washington Post columnist Joe S. Jackson’s prediction that Pelty was “not done yet, and is one of the wisest pitchers in the game,” proved inaccurate, as Pelty was bombed in his first outing with the Orioles, then relegated to mop-up duty. At the beginning of the 1913 season, Pelty was sold to the Minneapolis Millers of the Northern League (not to be confused with the American Association team of the same name), then sent back to the Orioles. But Pelty never pitched for them again; manager Jack Dunn lamented that he was useless.

After his playing days ended, Pelty dabbled in scouting, once recommending a pitcher who had lost his leg. Pelty continued his involvement in sports, coaching local area football and several semi-pro baseball teams including the Farmington Blues. He had also been coaching the Farmington High School baseball nine since at least 1906.

Much of his post-major league life he spent in Farmington with his wife, Eva, and their son, while running the book and merchandise store that had been started by his parents and continued by his older sister Gertrude. He also participated in local Republican party politics, serving as alderman of Farmington for several terms. Appointed in 1921 by governor Arthur Hyde as an inspector for the Missouri State Pure Food and Drug Department, he remained in that post through two successive Republican administrations, until 1933. Later, he became plant foreman for the Hafner Rock and Construction Company in Farmington. He died on May 24, 1939, shortly after a cerebral hemorrhage in his hometown. He was buried in the Masonic cemetery in Farmington, where today a mural pays tribute to him as one of six significant figures in the town’s history.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

A major source of information for came from a series of phone and e-mails with Lawrence Paul Pelty (grandson of Barney) in November, 2004. A phone interview with Bud Cole, 11/19/04, ballplayer with the Farmington Blues and Farmington resident, was also very helpful. Other sources:

The Barney Pelty file in the Farmington Public Library with articles from various papers, most significantly several obits (two without cite) and a series of photos with accompanying stories without cite.

Peter S. Horvitz, The Big Book of Jewish Baseball.

Robert Slater, Great Jews in Sports.

Rabbi Steven J. Rubenstein, “A Touch of Immortality: The Tobacco Connection, Part 1”, www. Shawngreen.net/articles2/jewishplayers/rabbi/page4.html

Washington Post

Chicago Daily Tribune

The Times of St. Louis

St. Louis Post-Dispatch (1908 April, May, July research performed by Steve)

The Daily Review (Decatur, Ill.)

Newark Daily Advocate

Sheboygan Daily Press

Retrosheet.com

baseballreference.com

BaseballLibrary.com

deadball.com

jewsinsports.com

Full Name

Barney Pelty

Born

September 10, 1880 at Farmington, MO (USA)

Died

May 24, 1939 at Farmington, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.