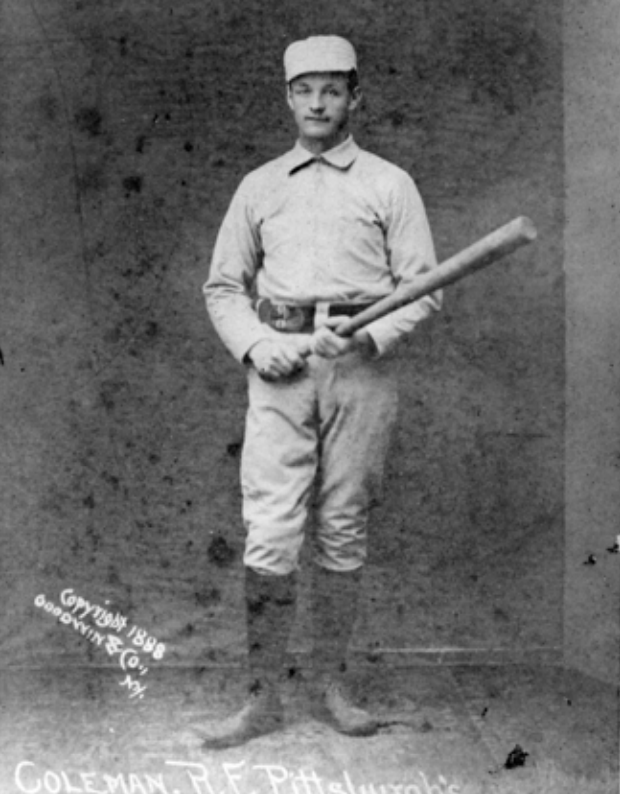

John Coleman

It takes a special kind of talent for a pitcher to lose 20 games in a season. The pitcher has to pitch both poorly enough to lose, but well enough that he keeps getting chances to pitch. If losing 20 games takes talent, how much more talent does it take to lose 48 games in a season? That is the case of the ill-fated Jack Coleman, who in 1883 became the biggest loser in baseball history.

It takes a special kind of talent for a pitcher to lose 20 games in a season. The pitcher has to pitch both poorly enough to lose, but well enough that he keeps getting chances to pitch. If losing 20 games takes talent, how much more talent does it take to lose 48 games in a season? That is the case of the ill-fated Jack Coleman, who in 1883 became the biggest loser in baseball history.

John Francis “Jack” Coleman was born to Irish immigrants John and Mary Coleman, though both his birthdate and birthplace are up for debate. Baseball-reference.com lists Coleman as having been born on March 6, 1863, in Saratoga Springs, New York. The original source of this information is a December 23, 1893, New York Clipper profile of Coleman.1 However, the 1880 census shows Coleman being born in Illinois circa 1860. To complicate matters further, Coleman’s death certificate provides a birth year of 1855 and a birthplace of Chicago. Based on contemporary accounts from his playing days and the census records, the 1860 birth year and Chicago birthplace seem most likely.

John was the fourth child born to the family. Coleman’s father died when John was young; Mary was listed as a widow and seamstress on the 1870 census. The Coleman family had emigrated from Ireland to Canada and eventually settled in Chicago between 1857 and 1859. Young John was listed as a druggist on the 1880 census and alternately as a clerk in the 1880 Chicago city directory. Coleman’s baseball career began around this time, when he appeared with the Acmes, a top Chicago amateur club.2

The first murmurings of Coleman’s potential as a pitcher began in 1882, with the Peoria Reds, one of the top semipro clubs in the Midwest. The Reds would join Organized Baseball the following year in the fledgling Northwestern League. Coleman drew notice when he struck out 37 men in two games against a Chicago amateur team.3 He was courted by the Fort Wayne Golden Eagles in September 1882, along with his catcher, Frank Ringo.4 Coleman is also credited with having attended or played for Syracuse University in 1882, but this appears to be untrue.5

Coleman and his catcher Ringo were in high demand and signed with the newly formed Philadelphia Phillies in November 1882. The Phillies were set to join the National League for the 1883 season. The duo was recommended to Phillies President Al Reach by the legendary Cap Anson, who had practiced with the pair in Chicago.6 This signing was not without controversy as Peoria Reds manager Charles Flynn indicated that the battery were reserved by the Peoria Reds for 1883 and claimed that the Phillies had stolen Coleman and Ringo.7 The dispute was eventually resolved, as Reach claimed that neither Coleman nor Ringo had signed with Peoria for the coming season.8 The fledgling Northwestern League gave up its claim to the players, seemingly to avoid conflict with the more powerful National League.

Coleman joined the Phillies for their first round of spring practice in late March. The club played the first exhibition game in franchise history at Philadelphia’s Recreation Park on April 2, 1883, against the amateur Ashland club from Manayunk, Pennsylvania. The young pitcher was up to the task and he no-hit the Ashlands and struck out 13 batters. The Phillies won by a final score of 11-0. The Philadelphia Times commented that Coleman “seems to have mastered all the known curves, and besides, has a slow, drop ball.”9 Reach and manager Bob “Death to Flying Things” Ferguson must have thought they had a great find in the right-hander. The Phillies and Coleman continued their strong play with three straight wins against local amateur clubs and two wins in Baltimore against the American Association Orioles. On April 16, over 6,000 people were in attendance to watch Coleman pitch against the rival Philadelphia Athletics. The eventual pennant-winning Athletics were no match for Coleman’s “low drop ball” and “very deceptive” delivery and the Phillies took the game by a score of 8-1.10 The club did not use Coleman again until April 26, when he was in the pitcher’s box for the club’s first loss of the exhibition season, 10-2 to the Athletics.

The Phillies and Coleman began their first major-league season on May 1 in Philadelphia, facing off against Charles “Old Hoss” Radbourn and the Providence Grays. Coleman pitched well and the Phillies staked him to a 3-0 lead going into the top of the eighth inning. Coleman unraveled and allowed four runs on a walk to Radbourn and hits by Jerry Denny, Barney Gilligan, Jack Farrell, and Paul Hines. The Grays held the lead and won, 4-3. This was the start of a losing trend for both Coleman and the Phillies. It was the first loss of Coleman’s major-league career and the first of more than 10,000 losses for the Phillies, baseball’s losingest franchise.

The following day, Coleman lost 4-1 to Radbourn’s Grays. He was back in the box again on May 4 for an 11-10 loss to Charles Buffinton and the Boston Beaneaters. Coleman started seven of the Phillies’ first eight games. He was spelled by right-hander Jack Neagle, who garnered the first regular-season win in Phillies’ history on May 14 in Chicago. Coleman got his first career win the following day in Detroit, with a 10-inning, 4-3 victory over the Wolverines. On May 28, he outdueled future Hall of Famer Pud Galvin in an 11-inning, 3-2 victory in Buffalo. By the end of May, the Phillies had a dismal record of 4-16 and Coleman had started 15 games.

Despite the club’s poor record, Coleman pitched quite well at times. He won back-to-back games for the first time in mid-June. On June 12, he defeated Jim McCormick and the Cleveland Blues 4-3 in 12 innings and followed it up with his first career shutout, a 2-0 victory over Galvin and the Bisons, on June 14. Two days later, on June 16, Coleman defeated the legendary “Pud” for the third time, 4-2. While Coleman was showing great potential, the Phillies were plagued by their inability to find a capable second pitcher. Jack Neagle was let go after a 22-4 shellacking by Buffalo on June 15. Rookie Edgar Smith was given a trial on June 20, but was clearly overmatched in a 29-4 blowout in Boston.

With this futility it is no wonder that Coleman started the next seven straight games. This included his second shutout, a 4-0 victory over Charlie Sweeney in Providence on June 26. Rookie right-hander Art Hagan was signed to spell Coleman and the duo alternated pitching duties throughout the summer. Coleman’s seeming dominance over Galvin ended in July, when he was battered by the Buffalo Bisons to the tune of a 21-6 loss on July 17 and a 25-5 demolition on July 19. It was clear that Coleman was exhausted, but due to the club’s small roster, the overworked right-hander was also used in center field and left field on his offdays. He was showing promise as a left-handed hitter and he would finish the year with a .234 batting average with 32 RBIs. On August 4, Coleman pitched a 6-0 shutout in Detroit over Stump Weidman and downed future New York Gothams star and future Hall of Famer Smiling Mickey Welch 7-3 on August 9.

The club then lost 14 straight games, including Hagan’s disastrous 28-0 loss to Providence on August 21 that led to his release. The newly acquired veteran Blondie Purcell broke the losing streak with two straight wins on September 3 and September 7. Despite the abysmal record of the Phillies, Coleman’s pitching was garnering positive reviews. Sporting Life described him as “a very quiet lad, a fair batter and a promising young pitcher.”11 Around this time, the American Association’s Cincinnati Red Stockings were reportedly interested in acquiring Coleman, but Phillies’ President Al Reach turned down the offer for the twirler.12

Coleman’s final victory of the 1883 season came in a 14-8 victory over Buffalo on September 19 in Philadelphia. This win would be his 12th of the year and his fourth over Galvin and the Bisons. Coleman made his final start in a 9-3 loss to Detroit on September 21 and he made one more relief appearance, on September 26. The Phillies’ inaugural season mercifully closed on September 29. The club finished a dismal 17-81, 46 games behind the first-place Beaneaters.

The young hurler experienced perhaps the most unique rookie season in all of baseball history. He finished with a record of 12-48, an ERA of 4.87, and 159 strikeouts. Using modern statistics it is possible to contextualize Coleman’s performance. While his ERA+ of 63 was considerably below average, Coleman was greatly hindered by the porous Phillies’ defense. The first-year franchise put up one of the most dismal defensive performances in history. The club committed 639 errors in 99 games, almost 100 more than the next worst team, while its.553 defensive efficiency rating remains the worst mark in National League history.13 Coleman’s FIP (Fielding Independent Pitching) was 3.34, a mark good for 12th in the league ahead of such established stars as Mickey Welch and Fred Goldsmith. Despite the pitcher’s relative effectiveness, the dismal team defense ensured that Coleman set multiple single-season records that will never be equaled. Apart from the record 48 losses, he set records for most hits allowed, 772, and most earned runs, 291. Remarkably, Coleman’s 538⅓ innings pitched were only good for a distant third place on the leaderboard behind the legendary workhorses Galvin and Radbourn.

The Phillies thought enough of Jack Coleman to place him on their reserve list after the season. In the offseason, Jack returned to his native Chicago. In February 1884, he competed in a handball match for a purse of $50. Coleman was described by the Daily Inter Ocean as “a well-known athlete and reputed to be a hard hand ball hitter.”14 On March 2, the Philadelphia Times reported that he was training with veteran outfielder Jack Remsen in a Chicago gymnasium.15 At 5-feet-9 and 170 pounds, Coleman was reputed to be a great wrestler and very strong. He was an early fitness enthusiast in a time when many of his contemporaries eschewed offseason workouts. In 1890, Sporting Life described Jack’s training regimen, noting that he “always had a penchant to show a huge forearm and biceps and a back full of hard knotty muscles, and accordingly haunted a gymnasium through the winter and swung clubs in the summer.”16

The 1884 Phillies would be managed by one of the game’s legendary figures, Harry Wright. Wright was the mastermind and star of baseball’s first professional team, the 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings. He would go on to manage baseball’s first professional dynasty, the 1872-1875 Boston Red Stockings of the National Association. His presence was enough for the Philadelphia Times to declare optimistically: “History will not repeat itself this year, so far as the Philadelphia Club is concerned, if the prestige gained by the new manager amounts to anything.”17

Coleman entered the 1884 season on a high note. The Phillies, led in part by Coleman’s pitching and timely hitting, had taken the second annual city series from the rival Athletics, six games to five. However, Coleman’s role as number-one starter was being usurped by 21-year-old rookie phenom Charlie Ferguson. Before his untimely death in 1888 at age 25, Ferguson had established himself as baseball’s greatest all-around player. Wright was determined not to overuse either man by the standards of the times, so he alternated Ferguson and Coleman in the pitcher’s box. Coleman was in left field for the Phillies’ 13-2 Opening Day victory over Detroit on May 1. The next day Coleman pitched a three-hit, 3-0 shutout over Detroit. Things were looking up when the club won again on May 3 over the Chicago White Stockings, giving the Phillies’ their first-ever three-game winning streak.

This brief flurry of success was short-lived. On May 5, Coleman was hit hard in a 12-7 loss to Chicago’s Larry Corcoran. He rebounded with a 12-1 win over Buffalo on May 12, but lost his next five starts to close out the month. In late May, the Phillies added the hard-throwing Jim McElroy to spell Coleman. Jack, not surprisingly, based on his usage thus far in his career, was now suffering from a lame arm. The Phillies continued to use him in center field despite his arm troubles. It was a different time: There was no disabled list in 1884 and unless a player was physically crippled, he was expected to play. By the time Coleman returned to pitching for a 16-6 blowout loss to the New York Gothams on June 10, the once promising Phillies were now 9-24.

Coleman’s right arm was well enough by late June that he had resumed regular pitching duties. The results continued to be lackluster, however, and Coleman’s health came into question again. After a 7-1 loss to Detroit on July 9, in which he was described as being “out of condition and having little speed,”18 the overworked hurler was removed from regular pitching duties. In just his second season, his pitching career seemed in jeopardy. Wright would give Coleman three more starts that summer, culminating with a 9-4 loss in New York on August 13. The following week, Coleman and his personal catcher, Ringo, were both released. Ringo had hit a dismal .132 in 26 games for the Phillies. The Daily Inter Ocean commented on Coleman’s release, chiding the Philadelphia management for overusing the young pitcher in the spring by having him pitch 19 consecutive games against the Athletics, which left him unable to “make a creditable showing in the box.”19 While the claim that Coleman pitched 19 straight exhibition games was fabricated, the damage done to Jack’s right arm through the Phillies’ abuse was very real.

Coleman and Ringo were not out of work long, as the Philadelphia Athletics of the American Association came calling and signed the battery in late August. After his arrival with the Athletics, Coleman was used in the outfield almost exclusively, despite fielding an abysmal .743 in 24 games. This was down from the already subpar .844 fielding average he had in 27 games in the outfield with the Phillies. Manager Lon Knight evidently was not confident in his new acquisition’s arm health and used Coleman to pitch only twice the rest of the season, 6-2 losses to the St. Louis Brown on September 7 and October 9.

Coleman’s final numbers for 1884 were below average. He went 5-17 with a 4.72 ERA in 175⅓ innings, just about as well as his rookie season but in far fewer innings. He hit .230, including a meager .206 in 28 games with the Athletics, while notching his first two career home runs. His arm injury, poor fielding in the outfield, and mediocre hitting would seem to suggest his major-league career was on the rocks. The Athletics must have seen something in spite of his poor performance. In late December, it was reported that Coleman would be the club’s starting center fielder and change pitcher for the 1885 season.20

The Athletics’ optimism was rewarded when on March 15, 1885, the Philadelphia Times reported that “Coleman has fully recovered the use of his arm and promises to do good service for the Athletics this season.”21 Jack was given the role of starting right fielder while his pitching appearances became increasingly sporadic. He would make just three starts and five relief appearances all season. The Athletics leaned heavily on the veteran Bobby Mathews as their number-one pitcher, which lessened the need for Coleman to pitch. In addition, Jack was still suffering from arm troubles; the June 24, 1885, issue of Sporting Life reported that “Coleman is not anxious to pitch. He says he can pitch a straight ball all day long, but as soon as he tries to curve his arm becomes lame.”22

Fortunately for the Athletics and for Coleman’s career prospects, he turned out to be a very good hitter and his pitching ability was no longer his main attribute. While he remained a below-average fielder, finishing the year with an .844 fielding percentage against the league average for right fielders of .879, he did have 23 outfield assists, good for fourth in the league. Sporting Life noted that “Coleman has shown great improvement as a right fielder since he first assumed the position and his batting is great.”23 Near the end of the season, Jack “badly strained a ligament near the elbow” during practice and it was feared he would be permanently disabled.24 The injury caused him to miss the final few games of the season and it was speculated that a permanent move to first base might be in his future.

Despite the injury, the former pitcher ended the 1885 season entrenched in the American Association leader board. In 96 games, he hit .299, good for eighth in the league. He added a .345 on-base percentage (10th), a .415 slugging percentage (10th), and a .760 OPS (ninth). He also added three home runs and was sixth in the American Association with 70 RBIs. His 133 OPS+ was good for 11th in the circuit. Despite Coleman’s strong hitting, the Athletics finished the season with a 55-57 record and a distant fourth-place behind the dynastic St. Louis Brown Stockings.

The 1885 season was the best year of Jack’s professional career and also brought significant changes to his personal life. He was married to Maggie, a Philadelphia native, in the fall and he spent his first-ever offseason in Philadelphia, relocating from his native Chicago. The Philadelphia Times reported in March 1886 that the former pitcher turned outfielder was training along with Joe Quest, Orator Shafer, Fred Corey, Jack O’Brien, and Jocko Milligan in a Philadelphia gymnasium. Jack was described as being “in excellent condition and his arm is now under perfect control.”25 It was suggested that Coleman would be expected to resume pitching duties in 1886 as well. The resuscitation of Coleman’s right arm was seemingly becoming a yearly concern.

The rumors of a move to first base proved unfounded; Jack opened the 1886 season as the starting right fielder for the Athletics. The proclamations of his return to the pitcher’s box proved mostly untrue: His only start of the season was a 5-1 victory over Cincinnati on July 5. In July, a well-known Philadelphia physician, Dr. Seth Pancoast, boasted that he could heal Coleman’s right arm with a months-long treatment, though it is unclear if this offer was ever taken up.26 It was apparent that despite these rumblings about Coleman’s pitching abilities, the Athletics saw his primary value as a hitter and used him as their number-three or cleanup hitter for the majority of the season. The breakout hitter of 1885 was slowed somewhat in 1886. Coleman’s batting average slumped to .246, with a meager .296 on-base percentage. While his average dropped by 53 points, he maintained his power with 16 triples and 65 RBIs in 121 games. The Athletics were not impressed with his play and released Coleman in September.

The rival Pittsburgh Alleghenys, on their way to a strong second-place finish, quickly snapped Coleman up and installed him in left field. His bat was rejuvenated and he closed the season with a flourish, hitting .349 with 9 RBIs in 11 games for the Pittsburgh club. He became a fan favorite along the way for his heavy hitting. His overall season numbers appear quite modest: a batting line of .254/.302/.355 with 74 RBIs and 29 stolen bases. In the context of the 1886 American Association season, however, his numbers were quite good. He completed the season with an above-average OPS+ of 108. His 17 triples were good for second place in the league, while his 74 RBIs were seventh.

Coleman returned to Philadelphia for the offseason, where the Philadelphia Times noted he was a “daily visitor to the gymnasium.”27 In November 1886, it was announced that Coleman and the Pittsburgh Alleghenys would become the first team to move from the American Association to the National League. The Alleghenys were one of the founding members of the Association, but despite a strong second-place finish in 1886, manager Horace P. Phillips was quick to cite the club’s shabby treatment in the Sam Barkley affair as a prime reason for the club’s jump to the National League.28 That affair involved St. Louis Brown Stockings second baseman Sam Barkley, who was put up for sale by St. Louis. The second baseman signed with both the Baltimore Orioles and the Pittsburgh Alleghenys in the spring of 1886. As a result of signing with both clubs, Barkley was suspended by the American Association, while its officials tried to determine which club had the rights to Barkley.29 Eventually it was resolved that Barkley would join the Alleghenys, but the aftermath left a bitter taste in the mouth of manager Phillips and his team.

The coming of the 1887 season brought the now-annual announcement in the media that Coleman would return to the pitcher’s box. Jack’s prospective return to pitching was reportedly motivated by the drastic rule changes that both the National League and American Association agreed to for 1887. The pitching distance remained 50 feet, but pitchers were now encouraged to start at the back of the pitchers’ box, making the true pitching distance 55 feet 6 inches. Meanwhile five balls would constitute a walk, down from six, and in the most galling change, it was announced that that batters would get four strikes instead of three. In January 1887, Coleman announced his intentions to pitch under the new rules and the Alleghenys were reportedly eager to comply.30

Coleman signed for a salary of $1,500 for the 1887 season.31 Despite his strong hitting, this salary placed him as one of the lowest paid players on the club, with the newly acquired former Cleveland Blues and Chicago White Stockings ace Jim McCormick commanding the largest salary on the club at $3,000.32 In late March, Coleman arrived in Pittsburgh filled with “confidence and vigor”33 to begin training with the club. Despite his confidence, it was reported in early April that his arm was “still too weak to permit his pitching this year in old-time form.”34 In lieu of Coleman’s return to pitching, it was predicted confidently that he would be “the patient man of the club this season as he makes every effort to secure a base on balls or a sure hit.”35 His speed also garnered attention when it was reported that he was the fastest man on the club, able to run the bases in 16 seconds.36 In mid-April, multiple reports suggested that Coleman’s arm was nearing full strength, but evidently the Alleghenys were not in agreement, and 1887 was the first year of his professional career in which he did not pitch.

With a strong rotation buoyed by his old rival, the indefatigable Pud Galvin, the hard-throwing left-hander Ed Morris, who won 41 games in 1886 as a 23-year-old, and 31-game winner Jim McCormick, the Alleghenys seemed like a strong pennant contender. The promise of the 1887 season would soon disintegrate into a tragic, tumultuous, and frustrating one for the Alleghenys. In July, veteran first baseman and team leader Alex McKinnon, batting .340 and in the midst of a career year was diagnosed with typhoid. He died on July 24. Left-hander Morris struggled to adapt to the new league and won only 14 games, while veteran McCormick, with over 4,000 innings under his belt, would struggle along to a 13-23 record in his final major-league season. Meanwhile, without McKinnon, the Alleghenys lineup was one of the league’s weakest, with Fred Carroll, Bill Kuehne, and Coleman being the only above-average hitters.37 The local media also blamed the club’s failures on dissension and booze, as the so-called “California clique” of Tom Brown, Carroll, and Morris was seen as a toxic and debaucherous force on the club’s morale.38 The team limped to a 55-69-1 record, good for sixth place, a far cry from their second-place finish in the American Association the previous year.

Despite the team’s struggles, Coleman turned in his third consecutive strong hitting season, with a slash line of .293/.337/.396 and a 109 OPS+. He chipped in two home runs, 54 RBIs, and 25 stolen bases. He also showed drastic improvement in the field, as he fielded .899 against a league average of .883 for right fielders. Sporting Life commented on his much improved defense, noting, “It is hard to realize to see his field work here that it is the same Coleman.”39 The Philadelphia Times even listed Coleman as the league’s best defensive right fielder on July 10.40 This was a remarkable turnaround from his poor fielding of the previous two seasons and a testament to his strong work ethic and adaptability. Coleman culminated his strong year, by becoming a father for the first time, when his son John Francis Coleman Jr. was born in Philadelphia on September 29, 1887.

Despite playing for the rival Alleghenys, Coleman remained a popular figure in Philadelphia. The local papers made frequent reference to his numerous friends in town and how well supported he was by his old hometown. As a show of gratitude, he was presented with a $225 diamond pin by the Philadelphia faithful on July 4.41 In the summer Coleman joined the Eagle Social Club with several other major leaguers including his old teammates Blondie Purcell, Cub Stricker, and Orator Shaffer. The Eagles would be a great help to Jack in the offseason of 1887, when he came down with an undisclosed illness. The November 16, 1887, issue of Sporting Life reported that the Eagles had offered him assistance while he was bedridden with an illness during the previous weeks.42 In mid-December, it was reported the Coleman was still sick but improving rapidly. On December 24, the Pittsburgh Post reported that Coleman was planning to retire due both to his illness and family pressure to quit, but also conceded that the threat might just “mean that John wants an increase of salary.”43

Coleman’s retirement threat proved to be short-lived. The January 11, 1888, Sporting Life reported that “Coleman, who attempted to play the mother-don’t-want-me-to-play-ball-any-more racket on Pittsburg, has returned to the fold and signed to play with the Smoky City team next year.”44 It was reported that Jack would play first base in the coming year since the Alleghenys had signed former Chicago White Stocking and future evangelist Billy Sunday to man right field. Despite this potential rivalry, Coleman and Sunday would become lifelong friends.45 Coleman continued working out daily at the gymnasium in the offseason and in March it was reported that he was once again “doctoring his elbow in hope that he may one day be able to pitch again.”46 Alleghenys manager Horace Phillips reported that while Coleman’s arm was improving to the point that he could now throw overhand, he would not be able to pitch due to pain in his elbow.47 It was rumored in early April that Louisville, Baltimore, Washington, and Indianapolis were all angling for Coleman’s release from the Alleghenys. Pittsburgh would not budge and despite spraining his ankle in early April in an exhibition game, Coleman was in the lineup when the season opened on April 20 against Detroit.

Somewhat surprisingly given the offseason rumors of a move to first base, Coleman was slotted in right field. It soon became evident that he was not fully recovered from his offseason illness. Both his hitting and fielding suffered in the first month of the season, and the Pittsburgh papers suggested that Irish-born outfielder Jocko Fields might take over in right if the poor play continued. The Pittsburgh Press asserted that Coleman’s poor play was caused by a blood-purifying medication that had impaired his eyesight and caused general weakness.48 Coleman’s demise was seemingly temporary; by the end of May he had regained his batting eye with a string of multi-hit games.

Coleman continued his streaky play all season long, with the local papers alternating between calling for his release and celebrating his return to form. At one point the Pittsburgh Press called him the weak point of the Pittsburgh outfield and lamented that he could no longer throw.49 Despite these complaints about Coleman’s defense and his poor arm, he still finished the season with 20 outfield assists in 91 games and a .928 fielding average against a league average of .902. Jack also saw time at first base, backing up future Hall of Famer Jake Beckley, who made his major-league debut in June. Coleman ended the year with his weakest hitting season since becoming a position player with a slash line of .231/.285/.274. In late September, Coleman reportedly made an offer of $1,000 to wrestle any man in the National League in a catch-as-catch-can wrestling match.50 Silver Flint, the Chicago catcher and a close friend of Coleman’s accepted the offer, but it is not known if a match ever took place.51

Despite his poor play and the criticism of the Pittsburgh newspapers, Coleman was reserved in October by the club. In December, Coleman’s fighting prowess was tested when he fought a mysterious Englishman after a debate about the “relative merits of base ball and cricket.”52 Coleman turned out to be no pugilist and was knocked down by his foe, ending the fight. Jack resumed baseball activities and participated in an indoor baseball game in Philadelphia on New Year’s Day 1889. In mid-January, he departed for Hot Springs, Arkansas, to train with teammate Fred “Sure Shot” Dunlap and Detroit Wolverines pitcher Pete Conway.53 Despite his best efforts to maintain his condition, Jack’s time with the Alleghenys was coming to an end. On April 26 he was given his 10-day release by manager Horace Phillips, as the club chose to keep pitcher-outfielder Al Maul for his ability to pitch occasionally.54

Fuming over his release and his poor treatment by the local press, Coleman wrote to Sporting Life, where he lamented the press’s criticism of his throwing arm and put up a $100 bet to any man on the club who could outthrow him.55 He received multiple offers from minor-league clubs, but was reportedly considering joining a touring wrestling troupe in lieu of any major-league offers.56 In mid-May, the Philadelphia papers strangely began to agitate for the Athletics to sign Coleman as a pitcher. This was unusual because Coleman had not pitched regularly since 1884 and the primary reason for his release from Pittsburgh was his inability to serve as a change pitcher. But Coleman was diligently practicing his pitching with Athletics catcher Jack Brennan, hoping for a trial with the club.57 The hard work paid off on May 27, when Coleman was signed on trial by the Athletics. Reports of his rejuvenated right arm seemed to prove true when he debuted for the Athletics by pitching a 6-1 complete-game victory over Cincinnati on May 30. The Philadelphia Inquirer wrote that Coleman “pitched a remarkable game … (and) had perfect command of the ball.”58 Coleman had adopted a now-antiquated underhand pitching style to compensate for his arm troubles.59 The prodigal right-hander’s triumphant return to pitching continued on June 6, when he defeated the last-place Louisville Colonels, 16-3. On June 20 against Columbus, Coleman made his only appearance of the season in the outfield when he replaced Harry Stovey in the fourth inning. Showing his rust, the left fielder made a crucial three-run error in the eighth inning that contributed to the As’ 7-6 defeat.

In July, when the A’s traveled west, Coleman was left at home and rumors of his release swirled.60 He remained with the club and next appeared on the mound in a 23-10 exhibition loss to the Atlantic Association’s Jersey City Skeeters on July 22.61 This poor result perhaps explains why Athletics manager Billy Sharsig was reluctant to use Coleman in the pitcher’s box despite his initial success. The Athletics were a strong club, had little use for Coleman in the field, and did not trust his health enough to use him regularly as a pitcher, even as the club struggled to find pitching. He returned to the pitcher’s box in early September, losing 8-3 to Kansas City on September 2. He defeated Kansas City 12-6 on September 4 in a seven-inning game for what would be his final major-league victory. He made his last start for the Athletics on September 9, lasting just two innings in a 10-7 loss to Louisville. In early October, Coleman was released and announced that he would sue the Athletics for his remaining salary.62 His final record was 3-2 in five starts with a 2.91 ERA, but his health remained an issue as he sought out his next major-league opportunity.

On January 2, 1890, the Pittsburgh Dispatch reported that Coleman might return to the Phillies, where he began his career in 1883. The article said that he had suffered from malaria in 1889, which explained his long absence from the Athletics. By October, the normally 170-pound pitcher was down to 138 pounds.63 But thanks to his workout regimen of “daily exercise, using dumbbells and Indian clubs,” he was now up to 188 pounds and experiencing “no pain in his pitching arm.”64 The Phillies’ rumors proved fruitless, so Coleman went to Hot Springs to work out with the Cleveland National League club.65 Failing to garner a major-league job, he joined the Toronto Canucks as an outfielder and pitcher at a reported salary of $2,100.66 He hit .280 in 49 games and was 11-3 as a pitcher. This prompted the Alleghenys to take an interest. The club, decimated by defections of nearly all of its top players to the rival Players League, was on its way to a miserable 23-113 record and a place on the list of worst major-league teams of all time. Desperate for pitching, the Aleghenys signed Jack on July 14 and he made his first appearance the following day in an 8-4 complete game loss to the Phillies. He started in right field on July 17 and was on the mound on July 18 in a 17-7 loss to Brooklyn. This was his final major-league appearance. He was released the next week. He actively sought another job, but found no takers for the remainder of the season.

The demise of John Coleman’s major-league career could possibly be traced directly to his overuse in 1883. Quite commendably, he was able to recast himself as a solid hitter and rapidly improving outfielder. He kept himself in great physical condition and overcame two serious illnesses to resume his career. However, Coleman never seemed able to let go of his hunger to pitch, though his right arm never recovered fully. Neither the Athletics nor the Alleghenys ever seemed entirely comfortable with him as a position player.

With Coleman’s major-league career now over, he embarked on the second phase of his career, as a minor-league journeyman. He applied for the Toronto manager’s job in 1891, but was unsuccessful.67 In June 1891, he signed to play first base for Lebanon, Pennsylvania, of the Eastern Association. He was released after hitting just .213 in 28 games. He was quickly signed by Omaha of the Western Association, but his batting eye had not returned and he was let go after hitting a meager .191 in 16 games.

Never one to be counted out, Coleman rebounded in 1892, hitting .342 while splitting time between Danville and Lebanon of the Pennsylvania State League. He followed up with another strong season in 1893, hitting .295 in 70 games split between York, Harrisburg, and Scranton. He also went 23-12 as a pitcher. He was reported to have signed with King Kelly’s Allentown team in 1894 , but he did not appear with the club.68

Coleman remained a prominent figure in Philadelphia sporting circles during this time. In early 1895, he was rumored to be taking up a wrestling career, with his former teammate Fred Dunlap as a financial backer.69 It is not clear if Coleman played baseball either professionally or semiprofessionally in 1895 or 1896. In 1897 he made his return to professional baseball. He began the year pitching for the Bristol, Pennsylvania, club and eventually joined the Philadelphia Athletics of the Atlantic League. He hit .242 in 32 games, primarily playing first base. His arm was finished, though, as he went 0-3, allowing 21 runs in 15 innings of work.

Coleman’s professional baseball career was over, though he would continue to play semipro baseball throughout Pennsylvania. After over a decade of living in Philadelphia, Coleman also became something of a nomad. He does not appear on the census in 1900 or 1910, perhaps because he was moving around so much. He was reported to be living in Harlem in 189970 and was said to have a good position in Pittsburgh in 1901.71 His release from the Homestead, Pennsylvania, semipro club was noted in the May 4, 1903, issue of the Pittsburgh Daily Post.72 Around this time, his son, John Francis Coleman Jr., was also beginning a baseball career. He played for various teams in the low-level minors from 1906 to 1910 and he was reported to be a protégé of Connie Mack.73

Coleman was back in Philadelphia in 1908 looking for work as an umpire.74 In 1909, it was reported that he was set to inherit $250,000 after the death of his brother Michael, though it is unclear if he ever received the money.75 On February 9, 1910, The Gazette Times reported that Coleman, now living in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, was being considered as the referee for the James J. Jeffries-Jack Johnson heavyweight championship bout.76 The article noted that Coleman had assisted Jeffries in his preparations to fight James J. Corbett back in 1900 and the two had remained friends. Coleman did not end up refereeing the fight and by 1912, he was living in Detroit.

A profile in the Detroit Free Press saw Coleman lamenting the easy life of current major leaguers. He boasted of pitching in 13 straight exhibition games on one spring-training trip and that it did not bother him at all.77 Coleman’s claim is apocryphal. In 1883 and 1884, he shared pitching duties for the Phillies in the spring. His claim that the overwork didn’t bother him also is problematic; after pitching 538 innings in 1883, he battled severe arm problems for the remainder of his career and never returned to full-time pitching duties in the major leagues.

Coleman remained in Detroit for the remainder of his life. He found work in a bowling alley. He died on May 31, 1922, at the approximate age of 62 after being hit by an automobile.78 He was survived by his son John Jr. and three daughters.

John Coleman’s career was a fascinating one with many facets. While he is almost singularly remembered for the remarkably futility of his rookie season in 1883, he deserves praise for reinventing himself as a hard-hitting and steady-fielding outfielder. He was also one of the earliest players to adopt a dedicated fitness regimen and by all accounts was a good teammate and stable figure in an era when such men were not common.

In 1908, John Coleman was quoted in Sporting Life: “The dead are soon forgotten. In fact, most of us are lucky if we are not forgotten while we are alive.”79 This sentiment is a fitting eulogy for Coleman, who continued to persevere in his pursuit of diamond glory long after his major-league career was over. Let us not forget about John Coleman, who was much more than just baseball’s biggest loser.

This biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-reference.com, Familysearch.org, Genealogybank.com, LA84.org, Newspapers.com, Retrosheet.org, and SABR’s Biographical Project

Notes

1 “John F. Coleman,” New York Clipper, December 23, 1893.

2 “Charles Getzein, Pitcher of the Detroits,” New York Clipper, October 6, 1888.

3 “John F. Coleman,” New York Clipper, December 23, 1893.

4 “The Golden Eagles Still Soar,” Fort Wayne (Indiana) Sentinel, September 15, 1882.

5 The Syracuse University Archives has no record of Coleman attending the school. Mary O’Brien, Syracuse University Archives, email to the author, April 27, 2017.

6 “Coleman and Ringo,” New York Clipper, January 27, 1883.

7 “Base Ball,” Fort Wayne (Indiana) Daily News, February 8, 1883.

8 “O.K.,” Cincinnati Enquirer, February 18, 1883.

9 “The Philadelphias First Contest,” Philadelphia Times, April 3, 1883.

10 “Playing Ball in the Rain,” Philadelphia Times, April 17, 1883.

11 “League Pitchers,” Sporting Life, September 3, 1883.

12 “Looking for a Pitcher,” Sporting Life, September 17, 1883.

13 “BASEBALL: A History of Team Defense (Part I of II),” Baseball Crank, June 2, 2011, https://baseballcrank.com/archives2/2011/06/baseball_a_hist.php.

14 Daily Inter Ocean (Chicago), February 3, 1884.

15 “Base Ball Notes,” Philadelphia Times, March 2, 1884.

16 “A Player’s Career,” Sporting Life, December 27, 1890.

17 “The Philadelphia Club,” Philadelphia Times, March 23, 1884.

18 “Philadelphia Beaten,” Philadelphia Times, July 10, 1884.

19 “Other Games,” Daily Inter Ocean, August 21, 1884.

20 “Base Ball,” Philadelphia Times, December 28, 1884.

21 “Base Ball Notes,” Philadelphia Times, March 15, 1885.

22 “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, June 24, 1885.

23 “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, August 5, 1885.

24 “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, October 7, 1885.

25 “The Ball Players,” Philadelphia Times, March 14, 1886.

26 “The Local Season,” Sporting Life, July 28, 1886.

27 “Base Ball Notes,” Philadelphia Times, November 14, 1886.

28 “Hustling Horace Talks,” Philadelphia Times, November 28, 1886.

29 “Sam Barkley,” BR Bullpen, baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Sam_Barkley.

30 “Base Ball Notes,” Philadelphia Times, January 9, 1887.

31 “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, August 3, 1887.

32 Ibid.

33 “More Players Arrive,” Pittsburgh Post, March 24, 1887.

34 “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, April 6, 1887.

35 “Base Ball Notes,” Pittsburgh Post, April 9, 1887.

36 “Base Ball Gossip,” Philadelphia Times, April 24, 1887.

37 As measured by today’s OPS+ statistic.

38 “Anson’s Great Work,” Pittsburgh Post, July 9, 1887.

39 “Philadelphia News,” Sporting Life, July 6, 1887.

40 “Base Ball News,” Philadelphia Times, July 10, 1887.

41 “Base Ball Notes,” Philadelphia Times, July 4, 1887.

42 “Pittsburg Pencillings,” Sporting Life, November 16, 1887.

43 “Coleman May Retire,” Pittsburgh Post, December 24, 1887.

44 “Washington Whispers,” Sporting Life, January 11, 1888.

45 “Auto Victim Diamond Star Back in 80’s,” Detroit Free Press, June 1, 1922.

46 “Base Ball Briefs,” Pittsburgh Press, March 15, 1888.

47 “Base Ball Briefs,” Pittsburgh Press, March 6, 1888.

48 “Sporting,” Pittsburgh Press, May 8, 1888.

49 “Sporting,” Pittsburgh Press, June 22, 1888.

50 “League Notes,” Chicago Tribune, September 17, 1888.

51 “Base Ball Notes,” Philadelphia Times, September 30, 1888.

52 “Philadelphia Pointers,” Sporting Life, December 26, 1888.

53 “Base Ball Notes,” Philadelphia Times, January 6, 1889.

54 “Coleman Released,” Pittsburgh Dispatch, April 27, 1889.

55 “A Blast From Coleman,” Sporting Life, May 8, 1889.

56 “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, May 22, 1889.

57 Ibid.

58 “John Coleman Pitches a Winning Game for the Athletics,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 31, 1889.

59 “About Coleman’s Pitching, Pittsburgh Dispatch, June 1, 1889.

60 “Sporting Notes,” Pittsburgh Post, July 8, 1889.

61 “The Athletics Done Up, Philadelphia Inquirer, July 23, 1889.

62 “Ball Notes,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) News, October 5, 1889.

63 “May Sign Coleman,” Pittsburgh Dispatch, January 2, 1890.

64 Ibid.

65 “Sporting Notes,” Chicago Inter Ocean, April 3, 1890.

66 “Base Ball Briefs,” Philadelphia Times, April 28, 1890.

67 “Toronto Tips,” Sporting Life, March 14, 1891.

68 “Glints From the Diamond,” Scranton Tribune, April 19, 1894.

69 “Sporting Notes,” Pittsburgh Press, January 5, 1895.

70 “New York News,” Sporting Life, November 18, 1899.

71 “Pittsburgh Points,” Sporting Life, August 3, 1901.

72 “Pirates Here All This Week,” Pittsburgh Post, May 4, 1903.

73 “Off to Join Danville,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 28, 1908.

74 “Local Jottings,” Sporting Life, June 20, 1908.

75 “Local Jottings,” Sporting Life, September 25, 1909.

76 “Pittsburgh Bettors Get a Hard Bump,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, February 9, 1910.

77 “Old Timer Thinks Present Day Stars Have an Easy Life,” Detroit Free Press, January 19, 1912.

78 “Auto Victim Diamond Star Back in 80’s,” Detroit Free Press, June 1, 1922.

79 “Wise Sayings of Great Men,” Sporting Life, June 27, 1908.

Full Name

John Francis Coleman

Born

March 6, 1863 at Saratoga Springs, NY (USA)

Died

May 31, 1922 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.