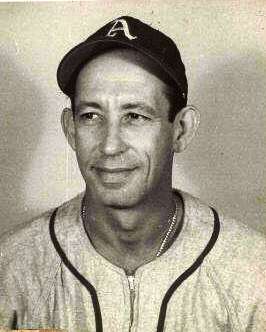

Mike Guerra

For as long as he could, Fermín “Mike” Guerra kept playing baseball all year around, in his native Cuba and in the United States. The two lands obviously had quite different cultures, baseball and otherwise, and Guerra even told Roberto Gonzalez Echevarría that he had been initiated into santería, the particular syncretic Afro-Cuban religion.1 Fermín Guerra Romero was born in Havana on October 11, 1912. His father and mother, Fermín Guerra and Cecilia Romero, came from a Spanish possession, the Canary Islands. His father worked as a commission merchant, which may or may not sound more grandiose a trade than it actually was. The phrase could apply to a street vendor.

For as long as he could, Fermín “Mike” Guerra kept playing baseball all year around, in his native Cuba and in the United States. The two lands obviously had quite different cultures, baseball and otherwise, and Guerra even told Roberto Gonzalez Echevarría that he had been initiated into santería, the particular syncretic Afro-Cuban religion.1 Fermín Guerra Romero was born in Havana on October 11, 1912. His father and mother, Fermín Guerra and Cecilia Romero, came from a Spanish possession, the Canary Islands. His father worked as a commission merchant, which may or may not sound more grandiose a trade than it actually was. The phrase could apply to a street vendor.

His family were isleños, Canary Islanders who had come to Cuba looking for better opportunities, a group that also included the family of Cuban pitcher Conrado “Connie” Marrero. 2 Many of them were brought to Cuba as laborers to work on building the railroads and other infrastructure. Guerra was illiterate and raised in poverty. He may have attended primary school for six years, as he claimed on his player questionnaire for the Hall of Fame, or may not have attended school at all, as reported by Gonzalez Echevarría. He batted and threw right-handed and described himself as 5-feet-10 and 155 pounds. Gonzalez Echevarría says he began in baseball playing in the Cuban capital’s empty lots, and then as a batboy at Havana’s Almendares Park, working for the team he would later manage.

Most Cuban teams at that time were amateur. Rather than receive a salary, players were expected to cover their own expenses and not be paid for play. Guerra “could not afford the amateurs,” he told Gonzalez Echevarría in an interview on August 8, 1991. As a small boy, he made his living selling “fruit and vegetables from a basket in the Plaza del Vapor, the huge Havana market” but fortunately found himself able to make a little something playing semipro baseball for Acción Cubana. Among the other teams he saw action with were Havana Electric3 and one named Chevrolet. 4

Baseball was played with a passion and at a very high level in Cuba; a number of Cuban ballplayers were signed to play in the United States. The two spheres – Cuban League baseball and organized baseball in the United States – co-existed rather well in the 1930s, and a number of American teams traveled to Cuba for exhibition games before the outbreak of the Second World War. Immediately after the war, the spring exhibitions resumed (the Red Sox, for instance, played some spring games in Havana) but rather quickly it became evident that a new accommodation or arrangement was necessary. The Pasquel Brothers of Mexico were active in trying to sign U. S. major leaguers to play in their Mexican League (they traveled to Havana and made lavish offers there to players such as Johnny Pesky and Ted Williams). The advent of integration in 1947 with Jackie Robinson, and others soon to follow, changed baseball in the United States. Underlying it all, there was also the return to action of hundreds of ballplayers – such as Pesky and Williams, and Robinson – who had been in military service during the war.

Guerra started his professional career well before the war, late in 1934 and after the first of the two revolutions which bracketed his baseball career. After a suspension of the Cuban constitution, and a couple of coups, including 1933’s “Revolt of the Sergeants,” the man wielding power from behind the scenes was Fulgencio Batista. Though he didn’t take power personally until 1940, his firm rule truly began in January 1934, concluding a period of disruption. That November, when the 1934-35 Cuban League season began, with three ballclubs, Fermín Guerra was the main catcher on the Habana Reds (no political connotations to the color) ballclub. He had 99 at-bats in the 28-game schedule, batting .162 with one homer and seven RBIs under manager Miguel A. González. A fourth team, the Santa Clara Leopards, was added in 1935-36, with Martín Dihigo (11-2) leading the Leopards to first place. Guerra was the second catcher, behind Ramon Couto, collecting just 79 at-bats (.203) but having the opportunity to catch Habana’s new pitcher, Luis Tiant, in addition to the established Gilberto Torres. Many years later, the left-handed Tiant’s namesake son became a near Hall of Famer in the United States.

Legendary Senators scout Joe Cambria made Guerra among his first of many Cuban signings. Guerra trained with Washington in the spring of 1936, was transferred to Albany before the spring was over, had all of one at-bat, and then was with the last-place York White Roses/Trenton Senators for most of the ‘36 season (the York team moved to the New Jersey capital on July 2). Guerra hadn’t helped much on offense; he batted just .161.

From 1934 through 1955, he played 20 seasons of Cuban League baseball, the only exception being the 1948-49 season when he served as manager of Almendares and did not play. Among the teams he played for in the league were (in sequence): Habana, Marianao, Almendares, Almendares, and Marianao, with one year of independent ball for Oriente in 1946-47. His average over all the years was an even .250. He managed from 1946-47 through 1960-61, the independent Oriente team first of all, and then Almendares for five seasons, Marianao for three, and Habana for three. He ranks fourth in the number of years played and fifth in at-bats, seventh in hits, and ninth in runs scored, ranking 10th in RBIs. 5

The reigning world champion New York Giants visited Havana 2½ weeks in late February and March 1937, and played a series of seven games against various Cuban teams – winning only two of them. Guerra caught pitcher Rodolfo Fernandez in the March 6 game, a 4-0 four-hit shutout administered the Giants. Guerra spent most of 1937 playing for Jake Flowers and the Salisbury Indians, a Class D team in the Eastern Shore League affiliated with Washington. He hit .296 with 14 home runs. Salisbury went from last place in 1936 to first place in 1937, took the pennant and the playoffs, and saw the “fleet-footed Cuban” Guerra named the All-Star catcher for the league.6 Planning almost three weeks ahead, Washington owner Clark Griffith announced that pitcher Joseph Kohlman, who’d won 22 games in a row, would start on September 19 and pitch to his batterymate, Fermín Guerra.

Kohlman’s debut turned out not to come until one week later, on the 26th, but Guerra debuted with the Senators on September 19, 1937 – and then didn’t play again in the major leagues until 1944. That first appearance came in the second game of the Sunday September 19 doubleheader against the visiting Chicago White Sox. The Senators won the first game in the bottom of the ninth, 5-4. Starting in the second game was pitcher Red Anderson, also making his major-league debut. Guerra was the catcher, batting eighth. Anderson couldn’t get through the third, and by the time he was pulled, the White Sox had a 7-0 lead. They won the game, 9-1. Chicago’s Vern Kennedy threw a five-hitter and Guerra was 0-for-3 at bat, striking out twice. He had three putouts (on strikeouts) and made one foolish error, throwing the ball wildly to second base (and into center field) in an attempt to cut down Mike Kreevich, who was running toward second. The problem was that Anderson had thrown ball four and Guerra’s throw wouldn’t have resulted in an out even if it had beaten Kreevich to the bag. The game was called after eight innings on account of darkness.

The Post’s Shirley Povich called it “a downright horrible debut” and wrote that he doubted Guerra would be in manager Bucky Harris’s plans for 1938.7

One imagines Guerra ran his debut game through his head for a long time. Had the ninth inning been played, Guerra would have been up fourth and might have had another chance at a hit. As it was, he had the one game and then six more years of waiting to return to the majors.

That winter, Guerra returned to Cuba, catching for Marianao and manager (and future Hall of Famer) Martín Dihigo, hitting .286. He was back with Salisbury, for 19 games, in 1938 and hit .323, plaing a couple of games in Class B with the Charlotte Hornets, too. In 1938-39, he was back with Almendares catching for Luque’s team. More Americans were joining some of the Cuban teams. The catcher for Santa Clara that year was one Josh Gibson. One of Guerra’s teammates was another Hall of Famer, shortstop Willie Wells. It goes without saying that this was first-rate baseball.

Guerra got in a much fuller season in 1939, in Class B South Atlantic League ball playing for the Greenville Spinners and hitting .321. Almendares won the Cuban League title, Guerra hitting .264. In March 1940, the Cincinnati Reds came to Havana and lost an 11-7 game to the Cuban All-Stars at Tropical Stadium. Three days later, in front of 12,000 fans on March 24, Guerra caught two pitchers of note, Adolfo Luque and Luis Tiant, as the Cubans battled the Reds to a 4-4 game. (It had to be called in the 10th so Cincinnati could catch their boat.) Then the St. Louis Cardinals showed up for some games, winning the March 28 game, 5-4. Three days later, in front of another capacity crowd at Tropical, the Cubans held the Cardinals to four hits, 4-2. A month after that, Mike Guerra was playing in Springfield, Massachusetts for the Eastern League’s Springfield Nationals, earning himself a headline in the Hartford paper when he tore off his mask and went after Hartford manager Jack Onslow, accusing him of excessively riding one of the Springfield players. The two were separated quickly enough, but then Onslow got into it with the umpire and found himself ejected from the game. Guerra knew enough English to know what Onslow had been saying and take offense. 8

He was a tough cookie. On July 13, he stepped too close to the batter and was hit so badly by a bat that he needed X-rays – yet he played two games the very next day, both at second base. At another point umpire Cal Hubbard was working a game when Guerra’s glove was knocked off by a batter during his swing and the umpire awarded first base for catcher’s interference. “Me no play,” Mike said, standing up and refusing to get back behind the plate. “Come on, Mike, act grown-up and let’s get on with the game,” pleaded Hubbard. “But all he says is, ‘Me no play.’ When he wouldn’t budge, I have to wind up throwing him out, but it had been bothering me ever since. How can you throw out of a game a player who’s refusing to stay in it?” 9

On October 5, 1940, Mike married Carmen Otero Gómez – the sister of Regino (Reggie) Otero, who played 14 games with the 1945 Chicago Cubs (hitting .391) and went on to coach eight major-league seasons with Cincinnati (1959-65 and the Indians in 1966). Guerra’s wife taught him how to sign his name and how to read and write a little. 10 Carmen and Fermín had two daughters whom he named on his Hall of Fame questionnaire in 1977: Carmen and Ernestina. A very brief profile, seemingly written in 1944, said he was a big boxing fan and the father of three daughters. A press release from 1947 said he was father to “four pretty dark-eyed senoritas.”

Yet another big-league club traveled to Cuba in the spring of 1941, and this time it was the Brooklyn Dodgers who learned first-hand that the Cubans could be difficult opponents. In the first of five planned games, the battery of Gilberto Torres and Mike Guerra held them to one run on five hits, winning 9-1. Durocher’s Dodgers turned the tables two days later, 11-4; Guerra had to be carried from the field in the third when Pete Reiser’s bunt went off his knee. 11 They split the series, two wins apiece and a tie. It was about a month before Guerra got back into action. He and Reggie Otero joined the Springfield Nationals for spring training at Anderson, South Carolina.

One month after that, he was called up to Washington, after they traded Rick Ferrell to the Browns in mid-May. He was ready to help, and it’s not as though the team couldn’t have used a kick-start from somewhere; from May 18 to May 30 the Senators lost 12 games without a win. Still, Harris was content to let Jake Early do the catching and didn’t put Guerra into even one game. After dropping a doubleheader to the Athletics on Memorial Day, when the Senators boarded the train for Chicago, Guerra wasn’t with them. It looked like he’d jumped the team: “He called for his pay check at Griffith Stadium yesterday and presumably headed for his native Cuba. During his five years with the Washington organization, Guerra has intermittently returned to Cuba A. W. O. L.” 12 Guerra had appeared in 20 games for Springfield (.300) and later in another 31 for Greenville (.244).

Even so, the Senators still didn’t cut ties. He played for Almendares yet again in winter ball and the Cuban team beat the Dodgers three games to two in an early March rematch. Guerra spent the summer with the Chattanooga Lookouts, Washington’s Class A-1 team in the Southern Association, hitting .308 in 116 games. With World War II underway and teams training closer to home during the spring of 1943, there were no visits to the island by American players, but Fermín Guerra was once more the All-Star catcher in Cuban League play. He hit .275 for Almendares and this year his eight stolen bases led the league. Havana’s Salvador Hernández was the choice for All-Star in 1943/44, but it was Guerra again in 1944/45. He’d not played in the United States during the 1943 season, but in 1944 it looked like Senators scout Joe Cambria’s work was going to pay off for Washington. Cubans were – at least at first – not subject to the military draft while playing in the US. And Cambria (though Italian himself) had locked up much of the talent from Cuba. It looked like a strategy that might really pay off for Washington. Shirley Povich noted, “The Cuban with whom Cambria is most smitten is Fermín Guerra…‘Guerra can do everything, and will make Washington fans forget Jake Early.’” 13

The fans were going to have to forget about Early, at least for a couple of years, because he passed his physical in February and was preparing for induction into the Army. Cambria promoted Guerra’s cause once more: “He’s an artist behind the plate and he can hit. And he’s fast on the bases.” 14 A snag seemed to crop up when six Cubans failed to show up in College Park, Maryland for the first week of spring training. Griffith was worried that one – or even all of them – might have decided to play baseball in Mexico instead. Manager Ossie Bluege was immensely relieved when the Cuban contingent turned up. Ten Latin players were depicted in a photograph which ran in the March 26 Post.

Rick Ferrell had come back from St. Louis by trade; he contended with “Cuba’s Mighty Mite” (Guerra) for the catcher’s job. Ferrell was an established veteran, heading into his 16th year of what was later recognized as a Hall of Fame career. Guerra, “a bantam model backstop,” was making a name for himself with his bat and seemed sure to stick. 15 A hand injury to Ferrell in the early going gave Guerra more playing time, too.

There was a scare in mid-July when the Cuban players were deemed “resident aliens” and received instructions to register for the draft within 10 days; word was that some of them – including Guerra – were leaving the team. On July 16, Guerra quit (with Gil Torres and Roberto Ortiz) and returned to Havana, but it was only for a short period of time before it seemed somewhat safe to return. He’d meanwhile been offered a contract to play ball in Mexico, but Griffith wouldn’t give him his release. Guerra registered for the draft, but not been called for a physical. He got into 75 big-league games in 1944, hitting .281 and otherwise posted stats similar to Ferrell’s but marginally better.

In 1945, he joined the team in mid-March and again was Ferrell’s understudy, but his average dropped off all the way down to .210. After the season was over, Gil Torres, Guerra, and others were warned not to participate in winter ball with other players whose status in organized ball was under question. The brothers Pasquel were approaching many of American baseball’s biggest stars and offering large bonuses to play in Mexican League baseball, there was then question raised as to whether or not Cubans who played in the Cuban League would be subject to the same sanctions as Major League Baseball sought to preserve its monopoly status. To be banned from playing American ball would have been disastrous economically for a player such as Guerra, should alternatives like the Mexican League not prove viable. It’s for this reason that he played the 1946-47 season for the Oriente ballclub (managing it as well) in the Liga de la Federación, a separate entity from the Cuban League.

Jake Early was mustered out of the service and re-signed with Washington in December 1945, but Rick Ferrell retired in February 1946. The Senators didn’t know if Guerra was coming back or not for the ’46 season. When Senators owner Clark Griffith was told that Guerra had been playing ball in Havana in November 1945, he said he had no information in that regard but alluded to unspecified “consequences” if that were true. 16 He’d reportedly been offered some good money to play Mexican League ball, and even taken a $2,000 advance from Jorge Pasquel. On March 13, however, the Los Angeles Times reported that Guerra had “reconsidered his Mexican contract and rejoined the Washington Senators.” It was relatively easy – the Senators had come to him, and were back playing some preseason games in Havana once more, including a couple against the Boston Red Sox. Apparently, Guerra was reluctant to give back the advance to Pasquel without a pay raise from Washington.

It all worked out, but Al Evans got most of the work during the 1946 campaign, Early got second-most, and Guerra got into just 41 games, hitting .253 and only driving in four runs. He almost left the team in late July, “insulted” when Evans was asked to play both games of a doubleheader in Cleveland and he had to sit on the bench. 17

Playing in the U.S. wasn’t always easy for Guerra. Even though he was of “white” ancestry, he was still Latino and a target of barbs from other ballplayers. He told Gonzalez Echevarría that “he was the object of quite a bit of bench-jockeying, much of it racial, but that he knew it was intended to make him lose his concentration and paid no attention to it.” 18 He played hard, and in his tribute to Guerra after Mike’s death, the sports editor of Miami’s El Nuevo Herald, Fausto Miranda, played on his last name: “Llevaba bien puesto el apellido, Guerra. El siempre estaba en Guerra para ganar un juego.” 19 On December 5, after nearly 10 years in the Senators system, he was sold on waivers to the Philadelphia Athletics, a last-place team two years in a row. Clark Griffith may have tired of him, saying, “We’ll get another young catcher before the season opens.” 20

In 1947, Mike Guerra hit .215 for Philadelphia, backing up Buddy Rosar. In 1948, he played in fewer games (53 to 72 the year before) and hit .211, again second to Rosar.

Before the 1948-49 season, an agreement had been reached between the Cuban League and Organized Baseball. 21 Guerra was the manager of Almendares in both 1947/48 and 1948/49, since Luque was still under ban, and ran a team which now contained a larger number of American ballplayers, including Don Newcombe, Chuck Connors, Jim Gilliam, Monte Irvin, and Sam Jethroe. For some, like Irvin, it was his second season of Cuban League ball. “Almendares’ triumph was not only due to the superior team the owners put on the field, but also to Fermín Guerra’s shrewd managerial mind. Aware that American pitchers slacked off toward the end of the Cuban season to reach spring training fresh, Guerra saved his native pitchers for the end of the campaign, because they would be more involved in the emotions of the championship.” 22

It was time for the first Caribbean Series, and the flag-winners, Almendares, were the Cuban entry in the February 1949 contest between teams from Puerto Rico, Panama, Venezuela, and Cuba – that first series to be played in Gran Stadium, Havana. There were some Cubans on the other teams, but the Venezuelan team had no Americans on its team (not being a party to the pact with Organized Baseball in the U.S.) Fermín Guerra was the manager of the Cuban team. His outfield was almost exclusively American: Al Gionfriddo, Sam Jethroe, and Monte Irvin, with Santos Amaro getting four at-bats. Cuba (Almendares) was undefeated, winning all six of its games.

He had a much better year for the Athletics in 1949, hitting .265 in 98 games, the first-string catcher on the squad after Rosar suffered a shoulder injury. He’d shown up late to spring training for the third year in a row and miffed Connie Mack, who put him on waivers. There were no takers (though whether Mack would have pulled him back had someone claimed him is unknown.) Mike was happy to be playing baseball in America, he said in an August 22 story carried by United Press. “When play regular, see ball better and hit better. Everything better all around,” he was quoted as saying. 23

Fermín Guerra was the Most Valuable Player for 1949-50 Cuban League baseball, as player-manager for the Almendares Blues, hitting .304 and helping lead his team to the flag. Guerra didn’t start the season playing, but once the ban on U.S. major leaguers playing for Cuban teams was lifted, he assigned himself the role as the team’s catcher.

The second Caribbean Series was held in Puerto Rico, in San Juan, in February 1950. Almendares represented Cuba once more, Guerra as manager, but it was Panama beating out Puerto Rico for the title. Guerra turned up late again – and an Associated Press story said, “The little Cuban catcher always waits until just before the start of the season to put in his arrival. By the time he gets into camp, the A’s usually have forgotten he is on the club – but, by the end of the season, Guerra almost has caught the most games of any of the A’s catchers.” 24 Unsaid here, but noted in other accounts, was that because Guerra had usually stayed in shape by playing ball in Cuba, he needed less time to get ready than most American ballplayers. He had another strong year for Philadelphia, batting for a .282 average – his career-best in the majors.

On December 13, 1950, the Boston Red Sox sold catcher Birdie Tebbetts to the Indians and bought Mike Guerra from the A’s. In February, the Red Sox bought Al Evans from the Senators. With Buddy Rosar on the team, it was like a reunion of sorts. Bucky Harris and the Senators were said to be hoping to buy Guerra from Boston. Having three Cuban pitchers (Conrado Marrero, Sandy Consuegra, and Julio Moreno) on his team, Harris could use the help in communicating with them. 25 Heading into spring training, the Red Sox weren’t sure which catcher (Guerra, Evans, Rosar, or Matt Batts) would be Steve O’Neill’s main backstop. “If O’Neill were to pick his man on defensive ability,” wrote Ed Rumill, “he probably would lean toward the cat-like Guerra, who also has a stinging bat, but does not hit the long ball.” 26 There was a minor squabble at the end of March over meal money, with Mike turning in his uniform, but things were worked out.

As it turned out, though, the Red Sox catcher for 1951 was none of the four. Instead, Les Moss, who came from the Browns on May 17, handled the lion’s share of the work. Ten days earlier, the Senators snared their man, buying Guerra for $25,000 and rookie catcher Len Okrie. Mike had only appeared in 10 games for the Red Sox, hitting .156 with two runs batted in. Now he was back with Washington. “I’m more interested in his catching than I am in his interpreting, but he figures to help us both ways,” said Harris. 27 This may have been more than a throwaway line; New York sports columnist Dan Daniel said Harris told him directly, “I simply have to get this Guerra to run my Spanish-speaking pitching staff.” 28

1951 was Guerra’s final season in major-league baseball. He accumulated 231 plate appearances and hit .201, with 20 RBIs. In all, Mike Guerra played in parts of nine season, hitting .242 (respectable for a catcher in his era) in 545 games and with 1,750 plate appearances. His career on-base percentage was an even .300. He scored 168 runs and also drove in 168 runs.

On the first day of 1952, Guerra got the job he wanted most, manager of the Havana Cubans, the Florida International League farm team of the Nats, taking over from Adolfo Luque. The job lasted just the 1952 season.

He wasn’t finished playing baseball, however. For the 1952-53 Cuban League season, Almendares replaced him as manager, hiring an American manager, Bobby Bragan. Guerra became manager with the Marianao Tigers, and gathered another 173 at-bats (.220). He hit .255 in 220 at-bats in 1953-54, and started the season in 1954/55 again as manager, but was replaced in midseason by Napoleón Reyes. He’d had seven hits in 41 at-bats (.167). That was his last season as a player. Figueredo’s Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball 1878-1961 shows him with a career batting average of .250 in 20 seasons of Cuban ball.

In 1954/55, Fermín’s brother-in-law Regino Otero had become manager for Cienfuegos. In 1956, the two came up against each other in the Caribbean Series, Otero and Cienfuegos being the winners, over a Venezuelan team that Guerra managed.

Guerra next turned up as manager for Habana for three seasons, 1958/59 through 1960/61. In his final season as manager (the final season of the Cuban League, given the advent of the Cuban Revolution), his winningest pitcher was Luis Tiant, Jr. In between, Guerra worked as a full-time scout for the Detroit Tigers, the appointment announced in November 1959. He scouted for the Tigers from 1960 through 1962.

In 1962, the first National Series after the revolution, Guerra managed Occidentales. Fidel Castro took some swings in the batter’s box to open the series. Guerra’s team went 18-9 to win the series, but Guerra himself “would soon fall from favor.” 29 “[He] was later sent to pick potatoes in Camagüey because of his resistance to the regime.”30 Guerra did get a second chance at managing in the Castro era, in the Sixth National Series (1967). Apparently he incurred the regime’s displeasure by listening to Voice of America radio.31

Fermín Guerra was elected to the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame in 1969, several years after the Hall was moved to Miami.

As late as 1977, Guerra was living on Calle Cristina in Havana, but no longer working for INDER, Cuba’s Institute for Sports, Physical Education and Recreation. (The “retirado” he entered on his Hall of Fame questionnaire may have obscured a lack of employment due to political differences with the regime.)

Two days before his 80th birthday, after a long struggle with heart disease, Guerra died at Mount Sinai Medical Center in Miami Beach. It was October 9, 1992. He was survived by his wife and daughters.

An updated version of this biography appeared in “Cuban Baseball Legends: Baseball’s Alternative Universe” (SABR, 2016), edited by Peter C. Bjarkman and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Bjarkman, Peter C. A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2007)

Figueredo, Jorge S. Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2003)

Figueredo, Jorge S. Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2003)

Gonzalez Echevarría, Roberto. The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999)

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Guerra’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, the online SABR Encyclopedia, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Gonzalez Echevarría, Roberto. The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 41

2 Ibid., p. 117

3 Ibid., pp. 204 and 219

4 El Nuevo Herald (Miami), October 10, 1992

5 Jorge S. Figueredo, Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961, pp. 158-160

6 The phrase comes from the August 31, 1937 Washington Post, in an article reporting that five key players had been sold by Salisbury to the Senators.

7 Washington Post, September 21, 1937. There is a confusing item to note parenthetically here. In his March 3, 1954 column in the Post, Povich wrote of Guerra, “He didn’t cotton to playing ball in the United States on his first trip with the Nats. They pulled out for Boston on the Federal Express one night and Guerra decided not to make the trip. He was homesick. They next saw him two years later.” What this refers to is unclear. In 1937, there were only 10 dates remaining in Washington’s schedule, during which they played 15 games. None of them was in Boston. All of them were home games except for the final series in Philadelphia, after hosting Boston. In an earlier column, in 1951, Povich told the same story but placed it in 1934, two years before Guerra is known to have been in the States, and during a year when Harris was managing the Red Sox.

8 Hartford Courant, April 27, 1940

9 Washington Post, December 6, 1955

10 Gonzalez Echevarría, op. cit., p. 406. A nice photograph showing both Guerra and Regino Otero appears on page 216 of Jorge S. Figueredo’s Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961.

11 New York Times, March 14, 1941

12 Washington Post, June 1, 1941

13 Washington Post, January 14, 1944

14 Washington Post, February 10, 1944

15 Washington Post, April 5, 1944. Povich said that Guerra had jumped the Chattanooga team late in 1943 to play ball in Mexico, but had been lured back by Joe Cambria.

16 United Press story dated November 19, 1945

17 Washington Post. August 3, 1946

18 Gonzalez Echevarría, op. cit., p. 270

19 El Nuevo Herald, October 10, 1992. “To say Fermín was to say ‘War.’ His last name suited him well. He was always in a war to win a game.” Miranda also wrote, in English translation: “He did not know how to lose. He spoke the same language as Adolfo Luque: ‘Defeats are not invented for winners.’”

20 Washington Post, December 3, 1946

21 Gonzalez Echevarría, op. cit., p. 67

22 Ibid., pp. 70, 71. Cultural differences often took a toll; the author adds that as many as 14 Americans had to be shipped from the Cuban League back to the States for one reason or another.

23 Hartford Courant, August 23, 1949

24 Chicago Tribune, March 29, 1950

25 Washington Post, February 4, 1951

26 Christian Science Monitor, March 1, 1951

27 Washington Post, May 8, 1951

28 New York World-Telegram, May 9, 1951

29 Peter C. Bjarkman, A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2007), p. 241

30 Gonzalez Echevarría, op. cit., p. 266

31 Pascual, Andrés. “Una Anécdota de Fermín Guerra y Chito Quicutis.” http://www.1800beisbol.com/baseball/Deportes/Beisbol_Cuba/Fermin_Guerra_y_Chito_Quicutis_Cuba/

Full Name

Fermin Guerra Romero

Born

October 11, 1912 at La Habana, La Habana (Cuba)

Died

October 9, 1992 at Miami Beach, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.