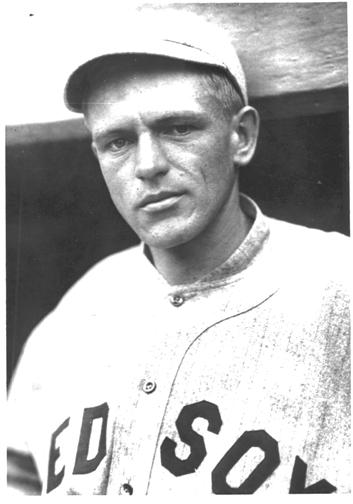

Fred Thomas

After eight years as a Boston regular, longtime third baseman Larry Gardner was sent by the Red Sox to Philadelphia in early 1918 as part of the Stuffy McInnis trade. Including McInnis, nine men were used at third base by Boston during 1918. Playing the most games at third (41) was 25-year old Fred Thomas. Thomas had arguably the most interesting season of any member of the Red Sox. He was a member of two championship teams (the Red Sox won the World Series and his Great Lakes team took the Navy Championship), had five future Hall of Famers as teammates, and played in seven games against the Chicago Cubs (six in the Series and one exhibition game while with the Great Lakes Naval team.)

After eight years as a Boston regular, longtime third baseman Larry Gardner was sent by the Red Sox to Philadelphia in early 1918 as part of the Stuffy McInnis trade. Including McInnis, nine men were used at third base by Boston during 1918. Playing the most games at third (41) was 25-year old Fred Thomas. Thomas had arguably the most interesting season of any member of the Red Sox. He was a member of two championship teams (the Red Sox won the World Series and his Great Lakes team took the Navy Championship), had five future Hall of Famers as teammates, and played in seven games against the Chicago Cubs (six in the Series and one exhibition game while with the Great Lakes Naval team.)

Fred Thomas was the grandson of immigrants. His grandfather, also named Frederick, was from the Hesse region of Germany. In 1880 Frederick was a saloonkeeper in Menominee Falls, Wisconsin. The second of his eight children, George, was born in Wisconsin about 1868. George Thomas became a carpenter and married in 1891. George and Martha Thomas had four children, only one living to adulthood. That child, Frederick Harvey Thomas, was born in Milwaukee on December 19, 1892.

George and Martha soon moved to the village of Mukwonago in Waukesha County, southeast of Milwaukee. This area would be Fred’s home through most of his baseball career. The Mukwonago area is still largely rural and a sizable lake is located near town. Fred enjoyed the outdoors. In addition to baseball, he fished in the lake and hunted on the nearby farmland. He also made money trapping muskrats in the lake. Trapping was lucrative, and Fred continued trapping even after entering professional baseball. He later remembered making almost as much trapping as he made during a season of professional baseball. Money saved from his offseason vocation later allowed Thomas to buy land in Northern Wisconsin on which he built a resort that is still operated by family members.

Fred played high school baseball and with the local Mukwonago team. During his high school career, he was seen by a scout from the Milwaukee City League. To preserve his amateur status, he played in the City League under the name of Wallace.

He graduated from Mukwonago High School in June, 1911, and almost immediately began his professional career. The day after graduation, George and Fred Thomas traveled together to Fond Du Lac, Wisconsin. Fred later remembered “being scared to death.” Fond Du Lac was a member of the Class C Wisconsin Illinois League.

When Fred and his father arrived in town, they went to the ballpark since the team was playing that day. It often took a little luck to break into professional baseball in 1911, and Fred Thomas remembered in a 1973 interview how that luck came about: “They had their team all set but — would you believe it — their third baseman got hurt that day. The manager of the club took a look at me and I know what he thought. He said, ‘Kid, do you think you can play third base?’ I said, ‘Sure I can play third base.’ So he says, ‘Tomorrow morning, I’ll hit you a few grounders to see what you can do.’ That infield was as smooth as glass and I thought they’d never get it by me there. So the next morning he hit me a few grounders and said, ‘I guess you’ll do.’”

Fred Thomas was in the lineup that very afternoon. “It was the first professional ballgame I ever played and I’ll never forget it. We played Rockford and they were the best team in the league. They had a pitcher by the name of [Cy] Slapnicka going for them — the best pitcher in the league, too. You know it was the best game I ever played as far as fielding is concerned. They hit more groundballs down towards third base and, boy, I got them every which way. I just had confidence on that good infield.”

Rockford broke a scoreless tie in the top of the ninth, but Thomas was presented a chance to become a hero. “We got a man on first base in our half of the inning and I was the next man to bat, to sacrifice. I’d never sacrificed in my life and so everyone was telling the manager what to do:: ‘You should put somebody up there to sacrifice for the kid.’ The manager said, ‘Nope, after the way he’s played today, I’m not putting anyone in there for him. I don’t care what he does. So I went up there to sacrifice and I made a half sacrifice down towards third base. The pitcher tried to get the man at second and he threw the ball a mile into right-centerfield. That man scored and I scored, too, and we won the ballgame.”

Thomas went with the team on a road trip to Aurora and Rockford. He said of those games: “I went along great, but I couldn’t seem to hit. I don’t know why.” After the last game at Rockford, manager Bobby Lynch received a phone call from the team president. “The third baseman was ready to play and we can’t afford to carry an extra man.” Lynch told Thomas, “I’ll just have to let you go home. I hate to do it. I’d rather let another man go and keep you, but they won’t stand for it.”

Thomas spent the rest of the summer playing semipro ball in Mukwonago, and late in the season got another chance at professional baseball. “Around Labor Day, the Green Bay club sold their third baseman to Los Angeles and called to ask if I’d finish the season. It was a funny thing. Where I couldn’t hit at Fond Du Lac, they couldn’t get me out at Green Bay. Playing in the sandlots around my home town, I got a bad charley horse and could hardly run up there [at Fond Du Lac].” Statistics for Thomas’ first professional season are unavailable.

That fall, Fred enrolled at Carroll College in Waukesha. He wasn’t sure if he wanted to continue in professional ball, but when Green Bay sent a contract that winter, Thomas decided to give professional baseball another try. Fred’s son Warren Thomas believes there was some parental influence involved, and that decades later Fred wasn’t entirely certain he had made the right choice. Thomas remembered having a good year in 1912, and he did. He batted .235 with decent power for the era.

Moved to shortstop in 1913, he was one of the league’s best infielders. He led the league with 127 games played, 81 runs, and 13 triples. He batted.290, stole 29 bases, and hit 10 home runs. Triples and home runs would prove lucrative for Thomas that season. “The Continental Clothing Company in Green Bay used to give $3.50 of merchandise for every home player that hit a three-base hit or a home run. I roomed with a fellow by the name of Earl Smith who also went up to the big leagues afterwards. I was just a skinny kid and everybody was kidding him because roommates used to split whatever they got. They didn’t think he’d get any help from me. Would you believe it? By the end of the summer we had a couple of trunks filled and didn’t know what to buy afterwards.”

Clothing wasn’t the only extra Thomas and Smith received for their hitting that summer. “With a home run you got a carton of Bull Durham tobacco and if you didn’t want that they’d give you $2.85 in cash. On one road trip at Wausau, I don’t know how many home runs Earl Smith and I hit, but we had enough to carry us on the whole road trip. The Bull Durham Company [also] put a big frame of a bull in the outfield and every time you hit the bull you got $50. I hit the bull the first year I played with Green Bay, and the second year I played with Green Bay, I hit it three times.”

Fred’s play in 1913 also impressed veteran manager “Pa” Rourke of the Omaha team of the Class A Western League. After his second season with Green Bay, Omaha drafted him in the fall of 1913.

Pa Rourke was legendary for his run-ins with Western League umpires. The Topeka Daily Capital said: “The stream of expletives which flows from Pa’s lips during the progress of a ball game is a never diminishing current five feet wide and eleven feet deep.” The manager was popular enough in Omaha that the 1914 team was nicknamed the Rourkes. Rourke was an astute judge of young talent. During the offseason he sold a pair of veteran infielders including former major leaguer Jim Kane to make room for Thomas and another young player. The Daily Capital was initially skeptical, but later wrote: “Thomas, the svelte blonde third bagster of the Omaha team, looks to be a pretty sweet ballplayer due to go higher some time.” Playing shortstop much of the season, Thomas maintained an average over .300 before finishing at .285 with excellent extra-base power.

Thomas was one of three future 1918 Red Sox third basemen to play in the Western League in 1914. George Cochran played third for Topeka and Jack Coffey was the manager-shortstop at Denver. Cochran and Coffey would remain in the Western League, but for Fred Thomas another promotion was in order. Drafted by Cleveland after 1914, he was assigned to New Orleans of the Southern Association After spending spring training with the major league team, Fred Thomas had another outstanding season at New Orleans in 1915. He hit .265, and led the league with 11 home runs and 53 steals. He later remembered, “I just about ruined that league.” New Orleans newspapers referred to him as “The Rabbit.” That season and a decision by the Boston Red Sox would soon change the course of Fred Thomas’s career.

In April, 1916, Boston dealt Tris Speaker to Cleveland for two players and an estimated $50,000. One of those players was Sam Jones, the other Thomas. A Boston Globe columnist wrote of Thomas: “It has been a long time since Boston has had a baserunner with a record of 53 stolen bases for a season. May Fred Thomas, the new infielder for the Red Sox, via the Speaker deal, be another Billy Hamilton. There is many a time when a fast man on the bases in place of a slow one means the winning of a game.” The Red Sox left Thomas at New Orleans for the 1916 season. Despite a disappointing season, Thomas was invited to Boston’s 1917 spring training camp in Hot Springs, Arkansas.

An early intra-squad game demonstrated Thomas’s strengths and weaknesses as a player. At the plate, he “twice tripled and drove in a run with a sacrifice fly. He kicked one in the field and pegged poorly to [Mike] McNally in the final frame.” Thomas remained with the Red Sox until they returned to Boston. He even got his first look at Ty Cobb that spring. When Boston played a pair of exhibition games at Toledo, Cobb was in the Mud Hens’ lineup, while Thomas watched from the bench. A few years later, Thomas would have a closer meeting with Cobb. “He slid into third base once and thought I got a little bit careless in touching him out. He called me everything he could think of — but he put himself out that time [and] he didn’t like that I told him that."

The Boston Globe said that when Harry Frazee informed Thomas he would be sent back to New Orleans for the 1917 season, “Thomas said he would go home first.” Instead he was sent to Boston’s Providence farm club in the International League. The Globe reported: “The recruit is satisfied with the Providence berth and said that he did not expect to stick with the Sox, saying that a club that was good enough to win the world’s championship should be good enough to stick together for awhile.” Playing in a top-classification league for the first time, Fred hit .252, tripled 16 times and stole 20 bases.

As 1918 began, the Globe reported that the Red Sox “had a string” on Thomas and several other players, noting that “there has never been a great demand for them.” The article said Boston was seriously pursuing a trade with the Philadelphia Athletics for first baseman Stuffy McInnis. When the deal was made, incumbent third baseman Larry Gardner was among three players sent to Philadelphia. Like the Speaker trade, this would have a profound effect on Thomas’s baseball future. The trade reduced the Boston roster to just 21 players with Thomas one of just two with previous experience at third. The appointment of Ed Barrow as the new Red Sox manager also improved Thomas’s chances of making the 1918 roster. Barrow, International League president the previous season, was aware of the young infielder’s abilities. Though it was a break for Thomas, he didn’t like Barrow’s noted temper, feeling that Barrow “blew his stack at times and not for good reason.” Warren Thomas says his father didn’t like hot-tempered managers.

Making the roster and being expected to start are two different things. As the time to report to the Hot Springs training camp neared, deals for infielders were a frequent topic in the Boston Globe. Fritz Maisel, Oscar Vitt, Eddie Foster, and Ray Chapman were some names mentioned. None of those deals was made, but Barrow expected McInnis to be “another Jimmy Collins” and announced plans to play him at third. Thomas arrived in Hot Springs on March 16, and a day later was the starting third baseman and cleanup hitter in the exhibition opener against Brooklyn. He went 1-for-3 with two runs scored, both on home runs by Babe Ruth. Thomas was still considered a utility player, and worked out at shortstop, second, and the outfield during the spring.

Throughout spring training, Boston was still seeking infielders. The Globe said: “The infield utility man is a hard working conscientious little fellow named Fred Thomas. He will probably hold his job; but he does not compare with either [Harold] Janvrin or [Mike] McNally.” He played in seven spring games for the Red Sox, batting .167 with a double and six runs scored. Defensively he made three errors in 21 chances.

Thomas spent the first week of the 1918 season on the bench, and made his major-league debut on April 22 against New York. He was unsuccessful in a pinch–hitting appearance against George Mogridge of the Yankees. Still the last man off the bench, Thomas next saw action late in another one-sided loss to Washington on May 8. Those brief appearances gave no indication he would soon receive an opportunity as a major league third baseman.

May 13, 1918, was a big day for Fred Thomas. Dick Hoblitzell was injured and Ruth was scheduled to pitch, so Barrow put Thomas in the starting lineup in what was supposed to be a temporary move. Fred didn’t think he’d play that afternoon, and even neglected to wear his sliding pad, not expecting to be in the lineup. As it turned out, this “temporary” lineup change lasted much longer than expected. Thomas got his first major league hit, off Allan Sothoron of the Browns, in the first inning of a 7-5 win. Hoblitzell was expected to leave for military service soon, but he was also batting .123 at the time of the change. Before his departure, he played only a handful of games, and Thomas remained in the starting lineup.

A mid-May series in Fenway against the Tigers convinced Barrow of Thomas’ abilities. In the first game of the series, he tripled in a run, the next day he scored three runs, and the following game he went 2-for-4 with an RBI. His defense was even more important. The Globe said he was “handling himself superbly at the hot corner. Freddy is doing everything to…Ed Barrow’s taste these days.” The first negative comment concerning Thomas had nothing to do with his playing ability. It was the likelihood he’d “be called any day in the draft.” Happily for Thomas and the Red Sox, any day was still over a month off.

During that month, Thomas played solid defensively with steady batting. He hit safely in 17 of 22 games and made just two errors during one stretch of June. Offensively he had back-to-back two-hit games during a series at Cleveland. Defensively he made an outstanding catch of a foul fly to help preserve Dutch Leonard’s no-hitter. Alert baserunning by Thomas gave the Red Sox a run in a game at Chicago. The Globe said: “Scott deposited a Texas leaguer in short right, good for one base. Thomas kept right on running and rounded third with the ball in [Eddie] Murphy’s hands. He pegged it to second and the run counted.”

On June 25, Thomas hit his only home run of the 1918 season. In a game at the Polo Grounds, “in the eighth he hammered a four-baser into the right-field stands” off Yankees pitcher Joseph “Happy” Finneran.

The next day, Thomas was injured making an outstanding play. The Globe said: “[Carl] Mays was well supported by the Sox, too, Thomas making a fine stop of [Peckinpaugh’s] savage grounder in the eighth. Thomas’s hand was injured in the play and he retired in favor of Heinie Wagner.”

Thomas made just one more regular season start in a Red Sox uniform. In early July, the Globe reported that he had left the team and was at his Wisconsin home for his pre-induction physical. The article stated: “Thomas was proving a sterling performer for the Barrowmen and will deliver the goods for Uncle Sam if the latter wants him….” Initially, Uncle Sam didn’t want Fred Thomas. He was rejected by the Army because of diabetes. Thomas said diabetes had been diagnosed after his second professional season. He remembered that the Army didn’t want diabetics and placed him in Class 4. He later amplified, “I didn’t know what to do. They said if you go back to playing baseball, we’ll have to pull you back because there was so much publicity about professional athletes being exempt from the draft. In this case we have to exempt you, but it would be a bad thing to go back playing ball. I asked them to give me a release so I could enlist in the Navy. They said they won’t accept you there. They’ll ask why you’re in Class 4. But I tried it. I went into Milwaukee and they hardly asked me to take off my clothes. They accepted me without an examination. So I went to Great Lakes as a sailor.”

The Great Lakes Naval Station was located in Chicago, and its commander, Captain William Moffett, was a baseball fan. “We are asking [baseball players] to join the navy because we want the best men we can get” he said. The Chicago Tribune, quoting Moffett, said there would be no permanent “shore duty” for the players. Thomas later said “[I] had it made at Great Lakes. All [I] had to do was play baseball.” The offer was attractive to a large number of talented players. More than a dozen men who previously or later played in the major leagues spent at least part of 1918 playing for Great Lakes. The team was managed by former major leaguer Felix Chouinard. Three of those players were future Hall of Famers: Red Faber in the Baseball Hall of Fame, and infielder Paddy Driscoll and outfielder George Halas in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Fred Thomas first appeared in the Great Lakes lineup in a 7-0 win over the Naval Auxiliary Reserve Officers Training School team. Thomas went 0-for-2 against Brooklyn pitcher Jeff Pfeffer. A few days later, plans were made for three games in the Chicago area with a team representing the Atlantic Fleet. Rabbit Maranville, Whitey Witt, and Del Gainer were the best known members of the Atlantic Fleet team. Before Thomas joined Great Lakes, they’d beaten the Atlantic Fleet team during an eastern trip. The two games at the Great Lakes park and one at Chicago’s Weeghman Park would determine the naval championship (though a couple of teams based on the West Coast were reportedly strong as well).

The first game was played on August 3, and featured pregame entertainment from a 300-piece battalion band. Captain Moffatt threw out the first pitch, and according to the Tribune, “Never had the air been rent with such bedlam…..fifteen thousand jackies yelled and cheered themselves hoarse.” Faber pitched Great Lakes to a 6-2 win, Thomas going 0-for-4. The Atlantic Fleet team won the next day, setting the stage for the deciding game. That game was the highlight of Fred Thomas’s time at Great Lakes. He had four hits, including a home run, against former Brooklyn pitcher Dick Durning. Faber got the win for Great Lakes in relief of aptly named starter John Paul Jones. Later in August, Great Lakes lost a pair of games to the Camp Grant Army team of Rockford, Illinois. Thomas had one hit in that series. He went hitless when Great Lakes hosted the Chicago Cubs (the Red Sox’ World Series opponent just a week later) on August 27. The Cubs won, 5-0.

As the World Series between the Cubs and Red Sox neared, it appeared Boston would use either Coffey or Cochran at third. Thomas remembered that Barrow had hopes of getting his third baseman back. “[He] sent me a telegram asking if I could get a furlough to play in the World Series because they were having a lot of trouble at third base, and my commanding officer got me a furlough.” He was the first major leaguer to receive a service furlough to play in the Series. When the Red Sox reached Chicago, they received a surprise. Edward Martin of the Globe informed readers: “Freddy Thomas was conspicuous. He looks as fit as an armful of fiddles and is in good shape. Thomas met the team at the hotel wearing his seaman’s uniform and the boys were so glad to see him they nearly shook his hand off.” It was also an opportunity for a family reunion: Thomas’s parents were at the games in Chicago. Fred’s father was described as “such a young looking gent that if he jumped into a uniform and stood down around the hot corner one would be almost willing to bet it was Freddy.”

Stability more than spectacular play characterized Thomas’ contribution in the World Series. Batting seventh, he singled once each in Games Three and Five. More important was his defense. Thomas played errorless ball and made a couple of outstanding plays in the deciding sixth game. The Globe’s Edward Martin considered the plays key to the Boston win: “Freddy Thomas knocked down a hard hit ball from Merkle behind third base in the seventh, the pill coming at him with such force that it drove him onto foul territory, but he held up, pegging while off his balance and getting Merkle with the assistance of ‘Stuffy the Stretcher.’ In the ninth, Thomas went out to the Cubs bullpen for Flack’s foul fly.” Thomas kept the ball Flack hit and had it autographed by his Red Sox teammates. In 2007, the baseball – the final ball put in play during the 1918 World Series — was put up for auction and ultimately repurchased for something over $12,000 by a member of the Thomas family. When the World Series shares were voted on by Boston players, Thomas received $750, about two-thirds of a full share.

With World War I ending in November, Thomas was soon discharged from the Navy. That winter, the Red Sox acquired Ossie Vitt to play third, and Thomas was sold to the Philadelphia Athletics. Boston had been trying to get Vitt for a year, but Thomas remembered uncertainty over his discharge also being a factor in the decision to trade for Vitt.

Playing in 124 of Philadelphia’s 140 games, he hit just .212, but tripled 10 times and his two home runs were against two of the league’s best pitchers, Dutch Leonard and Red Faber. Thomas enjoyed playing for Connie Mack, calling him “a gentleman to play for.” Thomas said of the 1919 Athletics: “We should have been better than we were but we just couldn’t make it. We had some fellows who didn’t play up to the standards they should have and we didn’t finish very well.”

In 1920, Thomas wrapped up his major-league career, playing in 76 games with the Athletics and three more with Washington. Fred later remembered: “Connie come up to me and said, ‘Griffith of the Washington club has been after me all year. He wants me to let you go to them because he needs a shortstop.’ I didn’t like the proposition but there wasn’t anything I could do about it.”

In late July, though needing a shortstop, the Senators needed a power hitting OF-1B more, and sought Frank Brower from the Reading ballclub of the International League. Reading demanded Thomas in trade. Thomas later said his seemingly inexplicable inactivity with Washington might have been an attempt to hide him from Reading. “I never could understand that. I did afterwards, though. When we got to the end of our road trip in Chicago, the traveling secretary said we’re going to let you go to Reading. Right then and there I had a notion to go home but I thought it’s the latter part of August and I might as well stick it out for the money. I found out the Reading club was supposed to have a choice of any of the infielders except one. When the Reading manager [John Hummel] found out I was in the Washington lineup, he changed his mind and decided to take me.”

Initially discouraged by the demotion, Thomas thought about retirement to finish his education. When the contract for 1921 arrived, his father suggested that Fred should at least write back to the team. “I wrote to them and told them I was going to quit if I couldn’t play in the big leagues. So they wrote and told me we’ll give you a big league salary. They gave me more money by $1,000 than I ever got in the big leagues.” He made $3,500 a season in the International League. Connie Mack, whom Thomas remembered as being stingy in terms of salary, had paid Thomas about $2,500 a season.

Fred Thomas was one of the best players in the International League in 1921. He batted a career-best .335. His 220 hits, 38 doubles, and 21 triples were also career highs,Thomas said diabetes may have cost him another shot in the major leagues after that season. “They were always afraid something was going to happen to me. The first year I was with Reading I did the same thing in the International League I did in the Southern League. I just about did everything in that league, and a scout for the New York Giants had it all fixed that I was going to go to the Giants but when they found out I was diabetic they just wouldn’t have anything to do with it.” Thomas remained in Reading for two more seasons. In neither season did he approach his 1921 totals, though he did lead the league with 17 triples in 1923.

Fred married Susan Sawyer at East Troy, Wisconsin, also in Waukesha County, on December 24, 1921. They’d known each other for several years. Her brothers had played baseball against Fred in the area. Eventually, they went on a double date to a ballgame in Chicago. They hit it off and soon began seeing each other. Fred and Susan had two sons, Robert and Warren. Thomas finished his professional baseball career at Buffalo in 1924. Son Warren was born in Buffalo during Thomas’s season there.

After his retirement from professional baseball, Thomas began a career that allowed him to follow his passion for the outdoors. He owned and operated the Fred Thomas resort at Birchwood, in northwest Wisconsin, until 1960. Thomas’s uncle was a homesteader in the area, and Fred regularly visited to hunt and fish. His uncle urged Fred to buy land across the lake. Though he had a nice home in Mukwonago, he moved to the Birchwood area late in 1925. Warren Thomas remembers that the material for the family’s first cottage on the lake had to be brought in by barge. Despite the remote location, the fishing brought guests in from the beginning. The Thomases met guests at the railroad station, several miles away, and bring them to the resort. Son Warren Thomas believes today that an eye for quality and continual improvements made the resort successful. Teammate Everett Scott from the 1918 Sox would spend six weeks every year fishing at the resort. Warren Thomas remembers that Scott enjoyed his privacy, and would tell business associates in Fort Wayne, Indiana, that he was in Canada. Other former players, including outfielder Bob “Braggo” Roth, were also visitors.

Thomas played semipro ball in Rice Lake, Wisconsin, after opening the resort. Rice Lake had a strong team featuring Thomas and former major leaguer Clay Perry. The team traveled through the region, often playing in tournaments. Thomas received $25 a game, the same amount as a week’s rent at one of the resort’s cottages. The Rice Lake team also played teams of barnstorming professionals after the major league season ended.

Even after his playing career ended, Fred Thomas still had a strong accurate arm. Warren Thomas remembers family snowball fights. “He could make a snowball and throw that darned thing standing on his head, almost, and hit us every time. We gave that up because we were getting hit every time and he threw it pretty darn fast. ”

During the winters, Thomas often went to Florida. Warren Thomas isn’t sure how they became acquainted, but in the 1950’s, Fred often went fishing with Braves third baseman Eddie Mathews. During spring training, Mathews and other members of the Braves were frequent dinner guests at the Thomas home in Florida. The family understandably prizes a Milwaukee team ball that includes the signatures of Mathews, Hank Aaron, and Warren Spahn.

A back injury suffered when he was hit in the back by a pitched ball at some point eventually led to chronic degenerative back problems that required surgery. The surgery didn’t go well, and Fred Thomas spent the last several years of his life in a wheelchair.

During the latter years of his life, Thomas continued to follow the game, but was a critic of modern baseball. He felt fielders “should never let a ball get by them. They’re wearing a bushel basket on their hands.” Thomas’s glove was described as a piece of leather with a hole cut in the center to hold the ball. Warren Thomas remembers that his father was also dismayed by high salaries in the game. “He said they’re getting fantastic salaries and they haven’t even put their shoes on yet.” Fred held particularly fond memories of Babe Ruth, feeling that he was the greatest player in baseball history.

Fred Thomas died at a nursing home in Rice Lake on January 15, 1986, the last survivor of the 1918 Boston Red Sox. In addition to his wife, Susan, and sons, Robert and Warren, he was survived by eight grandchildren and 12 great-grandchildren.

In 1993, Warren was among descendants of 1918 Red Sox players invited to Boston for the 75th anniversary of the championship season. The family received a plaque, and Warren Thomas recalls that it was “quite a thrill to walk around third base where my father played in 1918.”

Sources

Interview with Fred Thomas, circa 1973. Tape provided by Warren Thomas.

Interview with Warren Thomas, August 17, 2007

Atlanta Constitution, Boston Globe, Chicago Tribune, Topeka (Kansas) Daily Capital,

Washington Post

Rice Lake (Wisconsin) Chronograph, January 16, 1986

United States Census

World War I Draft Registration for Fred Thomas

www.townofmukwonago.us

SABR online Baseball Encyclopedia

Full Name

Frederick Harvey Thomas

Born

December 19, 1892 at Milwaukee, WI (USA)

Died

January 15, 1986 at Rice Lake, WI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.