No Minor Matter: Mid-Century Greatness in the Tar Heel State

This article was written by Bill Pruden

This article was published in When Minor League Baseball Almost Went Bust: 1946-1963

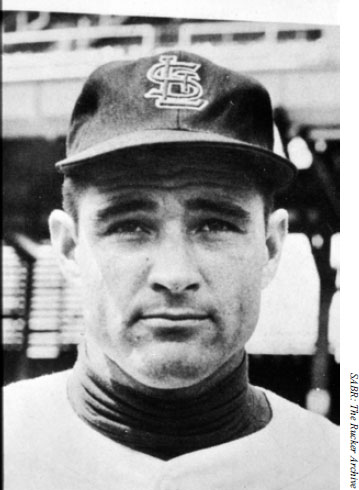

Wilmer “Vinegar Bend” Mizell. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, minor-league baseball enjoyed unprecedented popularity. The year 1949 marked its peak with the minors boasting 59 leagues and 448 teams.1 Nowhere was this renaissance more evident than in North Carolina. Baseball has long been popular in North Carolina—only Texas has had more cities and towns that have hosted teams at one time or another. The period from 1946 to 1951 saw the popularity of minor-league baseball in the Tar Heel State reach an all-time high.2 If a town did not boast a team, it wanted one and the number only grew. The 1946 season saw the state sporting 33 teams in six leagues. That number increased to 36 in 1947 and 44 in 1948, fueled by the creation of the Western Carolina League. There were 43 teams in 1949.3 No less reflective of the game’s health was the fact that attendance from 1947 to 1949 achieved levels that were not seen again until the 1980s, an especially impressive fact considering that from 1950 to 1980 the state’s population grew by just under 45 percent, shooting up from 4,061,929 to 5,881,766.4

The state also boasted a healthy contingent of Black players who played in a strong semipro circuit, and although there were no formal Negro League teams in North Carolina, these semipro teams served as something of a minor-league system of their own for the Northern Negro League franchises.5 Indeed, the popularity of baseball among the Black population was high and many towns of the times had both White and Black teams which, while strictly maintaining the segregation policies—both the legal and the customary—of the time, often shared the town’s ballparks for their games.6

As impressive as these numbers are, minor-league baseball in North Carolina was not just about the interest or the level of activity. Minor-league baseball in North Carolina was about more than, as the saying goes, just showing up. It was also about showing off, if you will, and the resultant quality of North Carolina’s minor-league baseball during this period was no less worthy of note. In fact, during this minor-league heyday, North Carolina was home to two teams, the 1950 Winston-Salem Cardinals and the 1951 Charlotte Hornets, whose performances earned them inclusion as numbers 61 and 36 respectively on the list of the “Top 100 Minor League teams of All-Time” that Minor League Baseball compiled and released in 2001 as part of the sport’s centennial celebration.7 For North Carolinians, the designations were a well-deserved pair of honors that recalled and recognized an important period in North Carolina sports history. It was an exciting time and while it didn’t last, the memories of those teams and their accomplishments, occurring against the backdrop of major changes in both the game and American society, make them worthy of study and celebration. This is especially true at a time when the place of both baseball and the minor leagues within the American sports landscape were being scrutinized as never before.

Bobby Tiefenauer. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

The 1950 Winston-Salem Cardinals were a phenomenon that captured the hearts and imagination of the Piedmont community. In a region that had no major-league teams, the minors not only represented the connection to the big leagues, but they were also a central part of the community, a form of entertainment, but more than that, a shared experience. Indeed, it was no accident that in 1949 Winston Salem mayoral candidate Marshall Kurfrees included a winning team for the city among his campaign promises, for he understood the role the team played in the community. It resonated with the city’s residents—and voters. Indeed, one commentator later said that the Cardinals’ championship run in 1950 all but guaranteed the success of Kurfree’s 1951 reelection effort.8

The group that did this was a distinctive, but at the same time representative, collection of baseball talent that came together as a team to produce one of the finest seasons in North Carolina baseball history. Termed “one of the more talented teams to ever play in the state” by author Chris Holaday, one of the most respected observers of the state’s minor-league landscape, the 1950 Cardinals totally dominated the Carolina League, ultimately finishing 19 games ahead of second-place Danville while compiling a record of 106-47, amassing a win total that remains the Carolina League record.9

With player-manager George Kissell pledging at the outset that the Cardinals would be “the hustlingest and runningest ball club” in the league, they won eight of their first 10 games and were never headed.10 And they won exactly as Kissell said they would, stealing four bases in their opener against Fayetteville, and pilfering a total of 16 in the first 10 games and 40 in their first 18.11 No less telling was the fact that twice in the season’s opening weeks hustling Cardinals baserunners scored from second base on infield outs.12 A young energetic team, one whose average age was only 20, they continued that fervid pace, ending the month of May with a mark of 30-11.13 But that was only the beginning as they would go on to achieve a record winning streak.

In the midst of the streak, in a colorful example of the relationship between the team and the city, as well as the spirit that infused the whole season, on June 14 almost 5,000 fans crowded into Southside Park to witness a pregame milking contest that included both players and managers from the Cardinals and the Raleigh Capitals. Cardinals pitching ace Wilmer “Vinegar Bend” Mizell won the contest and then went out to take a shutout and a 5-0 lead into the eighth inning. However, his milking effort apparently caught up to him and a tired Mizell gave up six runs—and the lead—in the inning. But in a way that marked the team’s effort all season, Jim Neufeldt hit a two-run home run to save the day and keep the streak alive. That win, the Cardinals’ 13th in a row, tied the 1948 record set by Burlington. The Cardinals won three more to extend the streak to 16—still the league record—before they came up short on June 16, losing to the Durham Bulls.14

The Cardinals were so dominant that they engendered significant jealousy around the league. On a number of occasions, the team found itself on the receiving end of fan abuse. The most noteworthy incident came after a pitch by Burlington pitcher Al Cleary broke J.C. Dunn’s arm: The Burlington crowd showered the defenseless Dunn with debris as he exited the field.15 Meanwhile, there were reports that the Burlington team officials refused to either call a taxi or provide a car to take Dunn to a hospital, leaving the Cardinals to do so in the team bus.16

All of this was a product of some impressive baseball talent. Reflective of the Cardinals’ depth of talent, only Lee Peterson’s 21 wins topped any of the major statistical categories. Peterson’s effort was only one of the many impressive pitching performances the Cardinals staff claimed. Beyond Peterson, the staff was anchored by future major leaguers—19-year-old Mizell, who posted a record of 17-7 with 227 strikeouts and a 2.48 earned-run average, and relief ace Bobby Tiefenauer, who almost matched Mizell, with 16 wins against 8 losses.17

On the offensive side, the team, which led the league with 782 runs as well as 88 home runs, was led by player-manager and third baseman George Kissell, who hit .312. Supporting Kissell were outfielder Dunn, who joined the team in early May from Omaha in the Western League and hit .307; outfielder Russ Rac, whose .287 average was the leader among those with enough plate appearances to qualify for the batting title; and shortstop Jon Huesman, who stole 43 bases on his way to scoring 116 runs.18 In addition, the team boasted a solid infielder, Earl Weaver, at second base. Only 19, Weaver hit .276 with 60 runs batted in and 57 runs scored in 127 games. That total was limited by a five-stitch spike wound, a midseason case of the flu,and, most debilitating, a broken thumb in August that sidelined him late in the season, although the feisty infielder returned in time for the postseason.19 Such resilience was typical for a player who even in his teens was recognized for his leadership abilities and a knack for winning, a talent that was evident in a minor-league career that saw him on league champion teams for each of the 1948-1951 seasons.20

It was a singular collection of baseball talent, and, in the end nothing could stop the Cardinals from fulfilling their destiny. However, Carolina League regular-season champs often fell short when it came to the playoffs and for all of their regular-season dominance, the Cardinals were well aware of the fact that not since 1945 had the regular-season winner survived the gauntlet of the playoffs to emerge as Carolina League champions.21 As the playoffs began, facing fourth-seeded Reidsville, the Cardinals seemed intent on burying the ghosts of the past and when they won the first two games, the mission seemed all but accomplished. However, they stumbled in Games Three and Four, but with Mizell on the mound for game five, they thrashed Reidsville 11-2 to take the series.22

They did not need such dramatics in the final series, dispatching Burlington—which had upset Danville in the other first-round match—in five games in the best-of-seven series. The first game was a nailbiter but the pitching that had been the team’s hallmark all year was again exceptional, holding Burlington scoreless until first baseman Neal Hertweck hit the first pitch he saw over the right-field fence in the 13th inning to secure the win.23 While they dropped Game Two, 6-2, the team quickly regrouped.24 Then, showing their mettle, they won Game Three despite getting only four hits. One of them was Gene Barth’s seventh-inning three-run home run that secured the 8-5 victory.25

On September 26 the Cardinals’ season-long mission was completed as Mizell scattered eight hits while Weaver’s bases-loaded single in the sixth inning provided the runs needed to bring the championship home to Winston-Salem. It also allowed the newly crowned Carolina League title holders to stake their claim to being the finest team ever to grace a North Carolina minor-league diamond.26

One of the competitors for that designation was the 1951 edition of the Charlotte Hornets. Coming just a year after the Cardinals’ heroics, the performance of the Hornets as they cruised through the 1951 TriState League schedule was no less dominant than what the Cardinals had achieved in 1950. The Hornets won the regular-season crown in spectacular fashion,completing the year with a record of 100-40 while finishing 15 games ahead of second-place Asheville.27 However, unlike the Cardinals, the Hornets were unable to continue the magic in the postseason, falling in stunningly unexpected fashion to fourth-place Spartanburg in the first round of the playoffs. It was a devasting finish to a season that had seemed charmed—one which, as it unfolded, had the makings of the kind of team that people would talk about for years to come.

Indications that it might prove to be a special season were there from the beginning. The team raced to a 16-4 start after 20 games, and while Asheville actually did them one better, opening with a 17-3 mark, the Hornets kept up their torrid pace. They reached first place on May 15 and never looked back, remaining in the top spot the rest of the season.28

Like the Cardinals, the Hornets were led by a player-manager—in this case, Cal Ermer. Ermer, who also manned second base, led by example (he batted .297) and through strength of character. He helped the club navigate the ups and downs of the long grind of the baseball season. Under Ermer’s leadership, they continued to put distance between themselves and second-place Asheville, which finished 15 games behind the Hornets.29 Indeed, given that record, as teams headed into the playoffs, the Hornets were riding high. As the top seed, they had earned the right to start at home, against Spartanburg, which had finished 27 games back of the regular-season champ.

But the Hornets quickly ran into trouble. In the opener, they lost a pitchers’ duel, 2-1. While Spartanburg garnered only four hits, it picked up one run in the first when a triple by Al Neil drove in Al Smith, who had singled. Then in the fourth, they sealed things on Tex Dargie’s home run.30 The Hornets regrouped in Game Two, securing a 4-3 win in another close contest.31 However, playing at Spartanburg, the Hornets lost a pair of one-run games. Game Three, a 9-8 heartbreaker for the Hornets, saw Spartanburg pitcher Don Van Nest take things into his own hands, hitting a game-winning eighth-inning home run.32 Then in Game Four, with their backs to the wall, behind 4-0 entering the top of the ninth, the Hornets fought back valiantly, only to lose 5-4, a loss that brought their magical season to a crashing halt.33

Reflective of the feeling the team had inspired in the Charlotte community, in the immediate aftermath of the gut-wrenching series of one-run losses, fans organized an impromptu farewell dinner on the night after the final loss, stressing the team’s accomplishments and not the deeply disappointing end. Manager Ermer spoke of each player. He highlighted his contribution, and each commentary summarized the ups and downs that characterized the season and minor-league baseball in general. It is a distinctive odyssey where every year young men, in pursuit of a dream, play their hearts out in the hope that one day they will make it to the big leagues.34 As Ermer talked about the pitcher Suvern Wright “who wanted to win [the team’s 100th] as much as any he ever pitched,” or Dick Guyton (“the best center fielder in the league and I don’t give a damn what they say about any all-star team”), or Buck Fleshman (“just 20 years old but he really did a job”), he was talking about the realities of minor-league baseball with its unique bonds.35

The fans’ gesture and Ermer’s remarks served as poignant reminders of the way minor-league baseball of that era was about more than just winning and losing, however important that was. It was also about a community connection; and this event represented a reaffirmation of the fans’ appreciation. It also reflected their determination that an unfortunate upset in the season’s final series would not be allowed to wipe away the rest of the season.

Further evidence of the bond that had been established between the team and its home city was the September 26 full-page advertisement appearing in the Charlotte Observer. Headlined “1951 Tri-State League Champions,” the ad featured an aerial view of the ballpark and the playing field and below it were the words: “The Management, Officials, and Directors of the Charlotte Hornets Baseball Club Wish to Express Their Appreciation to the Club’s Fans for Their Loyal Support During the 1951 Baseball Season.”36 In addition, soon after the season ended, Ermer was presented with a car from appreciative fans, further evidence of the chord the team had hit with the Charlotte community.37

In fact, the fans had it right. As disappointed as the team was, the early elimination could not wipe away an exceptional regular-season performance. Indeed, their domination of the Tri-State League was evident in virtually every major statistic. They led the league with a team batting average of .287; 940 runs (6.7 per game); 1,384 hits; 79 triples; 828 walks; and 819 RBIs. Reflective of the same keen eye that had garnered the league-high walk total, they also had the fewest strikeouts, 546. The Hornets’ only real offensive deficiency was a lack of power as the team finished seventh in home runs with only 40.38

As much depth as these team offensive figures reflect, the Hornets also boasted the league’s top individual offensive performer in Cuban outfielder Frank Campos. Campos crafted a .368 batting average—highlighted by a 27-game hitting streak that fell one short of the league mark. He had only 20 strikeouts in over 550 plate appearances. His average earned him the league’s batting title and, combined with his 103 runs batted in, helped him earn the league’s Most Valuable Player Award. He was the team’s only player selected for the Tri-State League’s all-star team. Indeed, that fact, to which Ermer alluded in his comment about center fielder Dick Guyton, had led team official Frank Howser to call the Tri-State League a “bush league,” asserting that given the team’s dominance, it was “an outright insult” that only one Hornet (as well as manager Ermer) had been chosen for the all-star team.39

All of this offense was complemented by a first-rate pitching staff, led by 20-game winner Levi “Buck” Fleshman, who posted a 20-9 record. He was ably backed up by Jerry Lane at 17-7, Bob Danielson with an 11-3 record, Mark Harley Grossman who posted a 10-2 mark, and Suvern Wright, who anchored the staff with an unblemished 7-0 record. And backing up the pitching staff was a defense that led the league in fielding percentage.40 While the season had not ended the way anyone associated with the Hornets wanted, the 1951 campaign nevertheless represented a historic achievement.

For most individual players, and even managers and coaches, the association with a minor-league team is usually short, often fleeting. The significance of a minor-league season is as often reflected in the subsequent careers for which they are part of the foundation as in their actual accomplishments. In many ways, their 1950 accomplishments notwithstanding, that was particularly true for the 1950 Winston Salem Cardinals, whose roster included a number of players who rose to greater prominence both in and out of baseball. Most prominent among the Cardinals alumni was Earl Weaver, whose time with the team, indeed, his whole minor-league career, was a precursor for his future Hall of Fame managing career. He never made it to the major leagues as a player, but his first managing assignment came in 1956 with the Knoxville Smokies. In 11 seasons as a minor-league manager, Weaver won three championships before he rose to the major leagues, moving from first-base coach to manager of the Baltimore Orioles in 1968. In 17 seasons, he led the team to six division titles, pennants in 1969, 1970,1971, and 1979, and a World Series championship in 1970. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1996.41

Meanwhile, for Weaver’s teammate, manager, and mentor George Kissell, whose calm hand was so important in guiding the young Cardinals team to the championship, the 1950 season represented an early stage of what became a legendary career in the St. Louis Cardinals organization as a minor-league manager and coach.42

Also noteworthy were the future careers of Mizell and Tiefenauer. Both went on to substantive major-league careers, with Mizell pitching for nine seasons from 1952 to 1962—he lost two seasons to military service. He compiled a career record of 90 wins and 88 losses with an ERA of 3.85. His best year was 1960, when a midseason trade landed him in Pittsburgh, where he was 13-5 for the pennant-winning Pirates. He made two appearances in the Pirates’ World Series win, making the start in Game Three.43 In addition, following his baseball career Mizell, who had settled in Midway, North Carolina, during the 1950 season, got involved in politics. He eventually won election to Congress in 1968. A Republican, he twice won reelection before being upset in 1974, a victim of the Watergate-fueled Democratic landslide.44

Meanwhile, Bobby Tiefenauer went on to spend at least parts of 10 seasons in the big leagues as a reliever. He played for six different teams during that span with his most successful year being 1964, when he recorded 13 saves for the Milwaukee Braves.45

While they did not boast the same level of later baseball accomplishments that the Cardinals did, some of the 1951 Charlotte Hornets took their careers to the next level. Star outfielder Frank Campos was not given much time to grieve the Hornets’ playoff fate, as he was called up by the Washington Senators soon afterward. Hitting .423 in eight games, he would play for the team in 1952 and part of 1953, in a major-league career that consisted of 71 games.46 Hornets catcher Bob Oldis had the longest major-league career of any team member, joining the Senators in 1953 and playing his final game with the Phillies in 1963, having spent time with the Pirates as well as back in the minors. Outfielder Bruce Barmes had a five-game major-league career as part of the 1953 Senators. Meanwhile, pitcher Jerald Lane’s 31 total games with the 1953 Senators and 1954-1955 Cincinnati Reds led the pitching corps, while Harley Grossman and Diz Sutherland both had the proverbial “cup of coffee,” each appearing in one major-league game.47

The two seasons enjoyed by the Winston-Salem Cardinals in 1950 and the Charlotte Hornets in 1951 not only represented the high-water mark of success and excellence in North Carolina minor-league baseball, but they came at the peak of the game’s popularity in the Tar Heel State and in that way their place in the state’s sports pantheon is even more secure. At the same time, those seasons in many ways represented the end of an era, for both of those seasons were played out against a rapidly changing racial backdrop in the United States. With Jackie Robinson having integrated the major leagues in 1947, joined in the ensuing years by the likes of Larry Doby, Roy Campanella, and others, the minor leagues would surely follow suit, and yet given the predominance of Southern teams in the minor leagues, it would not be easy. But it would come, changing the face of the game and the society it represented.48 In the meantime, the fans of the Winston-Salem Cardinals and the Charlotte Hornets could revel in the memories of having witnessed some of the best baseball the North Carolina minor leagues had to offer.

BILL PRUDEN has been a teacher of American history and government for more than 40 years. A SABR member for over two decades, he has contributed to SABR’s BioProject and Games Project as well as a number of book projects. He has also written on a range of American history subjects, an interest undoubtedly fueled by the fact that as a seven-year-old he was at Yankee Stadium to witness Roger Maris’s historic 61st home run.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article was edited by Thomas Rathkamp and fact-checked by Ray Danner.

NOTES

1 David P. Kronheim, “Minor League Baseball, 2012, Attendance Analysis,” Number Tamer, https://ballparkbiz.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/2012-minor-league-attendance-analysis.pdf.

2 Jim L. Sumner, “Baseball,” in William S. Powell, ed., Encyclopedia of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 94.

3 J. Chris Holaday, Professional Baseball in North Carolina: An Illustrated City-by-City History, 1901-1996 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2006), 5.

4 Holaday, 5; Historical Population Change Data (1910-2020). Census.gov. United States Census Bureau; https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/dec/popchange-data-text.html.

5 Gwendolyn Glenn, “Negro League Roots Found Deep in North Carolina History,” WFAE, September 4, 2020; https://www.wfae.org/sports/2020-09-04/negro-league-roots-found-deep-in-north-carolina-history.

6 Holaday, 199.

7 Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright, The 100 Greatest Minor League Baseball Teams of the 20th Century (Denver: Outskirts Press, 2006).

8 “Campaign promises …” North Carolina Collection, Forsyth County Public Library; https://northcarolinaroom.wordpress.com/2012/11/23/campaign-promises/. 1951 was the first of Murfree’s five reelection victories as he served as Winston-Salem mayor from 1949 to 1961.

9 Holaday, 189; Weiss and Wright, 129.

10 Jim L. Sumner, Separating the Men from the Boys: The First Half-Century of the Carolina League (Winston-Salem, North Carolina: John F. Blair, Publisher, 1994), 36.

11 Sumner, Separating the Men from the Boys, 36; “Carolina League Sidelights,” Danville (Virginia) Bee, May 18, 1950.

12 Sumner, Separating the Men from the Boys, 36.

13 Elton Casey, “Youthful Twins Run Durham Bulls Dizzy,” Durham (North Carolina) Sun, May 10, 1950.

14 Sumner, Separating the Men from the Boys, 36.

15 Sumner, Separating the Men from the Boys, 37.

16 Sumner, Separating the Men from the Boys, 37.

17 Weiss and Wright, 129-130.

18 Weiss and Wright, 129-130.

19 Bill Kerch, “Stars in the Making,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 11, 1950.

20 “Cardinals Spring Lineup Had Stan Musial, Earl Weaver,” RetroSimba: Cardinals History Beyond the Box Score, January 30, 2013, https://retrosimba.com/2013/01/30/cardinals-spring-lineup-had-stan-musial-earl-weaver/.

21 Sumner, Separating the Men from the Boys, 37.

22 Sumner, Separating the Men from the Boys, 38.

23 “Winston Cops Win in 13th,” Durham Morning Herald, September 22,1950.

24 “Burlington Bees Beat Winston-Salem, 6-2,” Raleigh (North Carolina) News and Observer, September 23,1950.

25 “Twin-City Takes Lead in Play-Off,” Durham Sun, September 25, 1950.

26 “Winston Cops Play-Off Title,” Durham Sun, September 27,1950.

27 Weiss and Wright, 240.

28 Weiss and Wright, 238.

29 Weiss and Wright, 238.

30 “Champion Hornets Lose First Playoff Game,” Sumter (South Carolina) Daily Item, September 6,1951.

31 “Charlotte Even in Play-offs,” Rocky Mount (North Carolina) Telegram, September 7, 1951.

32 “Peaches Beat Charlotte, 9-8,” Knoxville Journal, September 8, 1951.

33 “Peaches Eke Hornets, 5-4,” Greenville (South Carolina) News, September 9, 1951.

34 Eddie Allen, “Hornets Hit Peak With 100 Victories,” Charlotte (North Carolina) Observer, September 26,1951.

35 Allen, “Hornets Hit Peak With 100 Victories.”

36 “1951 Tri-State League Champions,” Charlotte Observer, September 26,1951.

37 “Hornet Manager and Remembrance of 1951 Flag,” Charlotte Observer, September 17, 1951.

38 Weiss and Wright, 238.

39 “Club Official Says Loop Is ‘Bush League,’” Macon (Georgia) News, September 6,1951; “Champion Hornets Lose First Playoff Game,” Sumter (South Carolina) Daily Item, September 6,1951.

40 Weiss and Wright, 238.

41 Warren Corbett, “Earl Weaver,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/earl-weaver/.

42 Warren Corbett, “George Kissell,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/george-kissell/.

43 “Vinegar Bend Mizell,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/m/mizelvioi.shtml; “i960 World Series,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/postseason/1960_WS.shtml.

44 Bart Barnes, “Wilmer D. ‘Vinegar Bend’ Mizell Dies at 68,” Washington Post, February 24, 1999.

45 “Bobby Tiefenauer,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.eom/players/t/tiefebooi.shtml.

46 “Frank Campos,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.eom/players/c/campofroi.shtml.

47 Weiss and Wright, 239-240.

48 Bruce Adelson, Brushing Back Jim Crow: The Integration of Minor-League Baseball in the American South (Charlottesville: University Press ofVirginia, 1999).