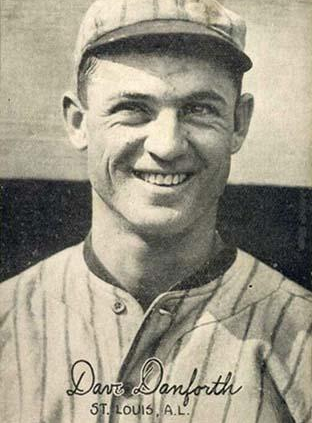

Dave Danforth

Dave Danforth (1890-1970) is one of the most fascinating and controversial figures in the history of the national pastime. He was “the icicle of the swirling vortex” for most of his career, and the mystery of what he threw and how he pitched has never been resolved.1 “Danforth, if you believe the boys in the dugout, did everything to the ball.”2 Over the course of a career that stretched from 1911 to 1932, he kept overcoming adversity. As J. Roy Stockton wrote, “It is doubtful if ever a professional athlete has encountered circumstances so discouraging as those which Dave Danforth has had to hurdle in the course of his baseball career.”3 Dave also had a remarkable knack for being involved in many significant baseball events, a Forrest Gump of the game.

Dave Danforth (1890-1970) is one of the most fascinating and controversial figures in the history of the national pastime. He was “the icicle of the swirling vortex” for most of his career, and the mystery of what he threw and how he pitched has never been resolved.1 “Danforth, if you believe the boys in the dugout, did everything to the ball.”2 Over the course of a career that stretched from 1911 to 1932, he kept overcoming adversity. As J. Roy Stockton wrote, “It is doubtful if ever a professional athlete has encountered circumstances so discouraging as those which Dave Danforth has had to hurdle in the course of his baseball career.”3 Dave also had a remarkable knack for being involved in many significant baseball events, a Forrest Gump of the game.

David Charles Danforth was born in the small farming community of Granger, Texas, on March 7, 1890, the fifth of six children of Charles and Henrietta Danforth. His father, who studied medicine in St. Louis and New Orleans and got his medical degree at Tulane, died when Dave was only 2 years old.4 His mother and her parents were born in Germany, while his father and his parents were American-born.5 Neither Dave nor any of his three brothers had sons to carry on the family name.6

Dave was a pitcher from his early days. He explained why: He was the biggest kid in the neighborhood and simply told the others that he would pitch—or there would be no game.7 He pitched in high school and at Baylor University, which he attended for two years. His second year, 1910-1911 he had a perfect 10-0 mark—including a no-hitter—and led the school to the Texas Collegiate Championship.

Dave was a tall, slender southpaw (listed at 6 feet, 167 pounds) who had caught the eye of one of Connie Mack’s informal scouts, Hyman Pearlstone, a grocer and banker from Palestine, Texas. He promised Dave a $500 signing bonus if he joined the Athletics. Dave made the trip to Philadelphia and showed up at Shibe Park early on the morning of August 1, 1911. That afternoon, manager Connie Mack inserted Dave into the game in relief against the first-place Detroit Tigers.

Dave soon proved crucial to the A’s pennant march. The team’s starting pitchers were worn down and benefited greatly from backup from the Texas youngster. The following week, he relieved Chief Bender in the 14th inning on Monday, Eddie Plank on Tuesday, Jack Coombs on Wednesday, and Harry Krause on Friday. He finished the season with a 4-1 record, with 12 of his 14 appearances in relief. Sportswriter Fuzzy Woodruff saluted Mack for finding another youngster from “some wild and woolly and unknown region . . . Danforth, from nowhere, came to the Athletics at a crucial period in their race. He came when the old hurlers were under a terrific strain.”8 Mack declared that he had found another Waddell: “Never seen a kid who had more prospects of being a corker.”9

Danforth was not eligible for the World Series, but as was not unusual with Mack’s s sharing club, he was awarded a full winner’s share of $3,654.58, at the age of 21.

In May 1912, after Dave had appeared in just three games, Mack decided to farm him out. The A’s were loaded with young pitchers: Byron Houck and Herb Pennock debuted that month. (Stan Coveleski and Joe Bush would join the team later that season.) Mack wanted Dave to get plenty of work, so he sent the lefty to Jack Dunn’s Baltimore Orioles.10 Years later, Mack said he let Danforth go because he didn’t have a curve ball.11 Mack may have had an option to recall him, but in late August, when he acquired Jimmy Walsh and Eddie Murphy from the Orioles, he may have had to cut Dave loose.12

Danforth joined Rube Vickers and Bob Shawkey as the anchors of the 1912 O’s.13 The following year, he led the Orioles with 304 innings pitched and pushed his win total up from 12 to 16. At the same time, he was thinking long-term, about his life after baseball. In 1913, he decided to enter the University of Maryland Dental School. The choice of dentistry seems odd. As we shall later see, Dave had enormous hands, and they were anything but delicate. Sometimes the most difficult questions have rather simple answers, and Dave’s son-in-law provided this one. Growing up in Granger, Danforth said he knew only one adult who could take off to play ball during the day—the city’s dentist.14

Jack Dunn provided Dave with a private room for his studies at spring training in Fayetteville, North Carolina, and the dental school’s dean allowed Dave to miss many of his classes and get lecture notes from a classmate.

Danforth tossed a shutout on Opening Day 1914, and the O’s starter the next day—making his professional debut—also threw a shutout: George Herman Ruth. That season, Dunn’s Orioles were on the front line of a war with the upstart Federal League, whose Terrapins team quickly devastated the attendance and thus the financials of the Orioles. When the legendary New York Giants faced the Orioles in an exhibition game that April (Dave beat them, 2-1), they drew a tiny crowd, while the Terps had more than 20,000 fans across the street for their opening day. By mid-season, Dunn had to generate cash to stay afloat and started selling players, including Ruth to the Boston Red Sox. A month later, on August 8, he sold Danforth to the Louisville Colonels of the American Association for $3,000.15

Before Danforth joined his new team, he moved up his wedding date by a few weeks and married 19-year-old Margaret Oliphant, a Baltimore girl. Dave won six games for Louisville and took part in a spirited pennant race in which his Colonels fell just short of Milwaukee. He returned to his studies and became the manager of the University of Maryland baseball team. He also received permission to finish his school year and report late to the Colonels. He graduated that spring but was not present at graduation, at which Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan delivered the commencement address.16

In the meantime Danforth started slowly but soon took his game to another level. He began experimenting with different pitches. When he struck out 11 men in relief on August 6, the Louisville Courier was surprisingly forthright in its description of the home-team pitcher: “He kept scratching the ball and roughing the surface until the visitors kicked about it.”17 Dave’s most effective pitch was one for which he became famous, as the Father of the Shine Ball.

Danforth explained how he stumbled upon the pitch, with two slightly varying accounts. The dusty field in hot and dry Louisville was regularly sprayed with oil, to keep the dirt from swirling. But the oily ball was hard to grip. According to one version, Dave would rub the oily ball on his pant leg. Under the other story, he would put rosin on his pants leg and rub the ball on it.18 In both accounts, in attempting to remove the oil, he made one side of the ball smoother and darker; hence “the shine”. Danforth said he got the idea by watching a bootblack shine shoes with a rag. The result of the contrasting surfaces of the ball (smoother and rougher sides) was similar to many trick pitches: a ball with an unpredictable flight, one it was hard to make contact with.

Danforth became harder and harder to hit as the season went on. On August 31, he won the first game of a doubleheader in relief and then pitched a one-hitter in the second game. After striking out 15 men on September 8, he tossed a two-hit shutout and struck out 18 Kansas City batters four days later. In doing so, he broke Marty O’Toole’s American Association record of 17.19 Just three days after that, Dave beat St. Paul, 1-0 and struck out 15 Saints.20 The current American Association record of 20 was set by Maurice “Mickey” McDermott on May 24, 1949.21

Chicago White Sox secretary Harry Grabiner saw Danforth pitch that month, and on September 28, 1915, after Dave won 12 games for Louisville, the White Sox drafted him. Dave Danforth was coming back to the majors.

Often the inventor of something is not the one who maximizes its use, whether in baseball or another endeavor. Elmer Stricklett (career record of 35-51) was one of the pitchers credited with introducing the spitball in the majors, yet his teammate and disciple, Ed Walsh, rode it to fame. In Chicago, Danforth showed the shine ball to a journeyman pitcher by the name of Eddie Cicotte. Up until 1915, Eddie had a record of 91-81; after that 13-12 season, he fashioned a 105-55 mark and became one of the game’s best pitchers.

F. C. Lane, the editor of Baseball magazine, said that Lefty Williams, Cicotte’s teammate, told him that Dave did indeed teach the shine ball to Cicotte.22 During that 1916 spring training, Dave befriended another pitcher who would later ride the shine ball to fame: Hod Eller.23 Eller did not make the 1916 White Sox (he would spend the season in Moline), but would be one of the aces of the 1919 world champion Cincinnati Reds.

Dave’s reputation was preceding him, and he was reputed to throw many more trick pitches than just the shine ball. Years later he was frank in admitting he experimented with many pitches: “I will admit that in my time I have used every delivery that I have ever heard of. If I had known of any others, I should have used them.”24 Dave was also often quick to note, “I never pitched an illegal ball in my life. Sure I invented the shine ball and used it until the pitch was ruled out with other freak pitching in 1920. I have nothing to hide.”25

The Sporting News spoke of his “new-fangled mystery ball,” a fastball “that did everything but talk.”26 One newspaper said that Dave used his large and powerful fingers—with the help of a rough fingernail—to loosen the cover of the ball and throw a “wrinkle ball.”27 More revealing was a report in The Sporting News that said the Minneapolis Millers had solved the Danforth mystery. He rubbed the ball on his uniform until one side was “as smooth as a billiard ball.” With one side rougher than the other, the effect was the same as that of the emery ball.28 At the time, Dave was not forthcoming about anything. He denied any changes to his pitching and said he threw just as he had in 1911.29

Once Danforth was back in the majors, his critics did not wait long to pounce. After he beat Detroit on April 13, 1916, Tigers’ manager Hughie Jennings accused Dave of throwing the emery ball.30 Tigers’ star Ty Cobb would point an accusing finger at Dave for years. In a syndicated newspaper series on his career, Cobb said the pitcher would slit the ball with a razor, load it with paraffin (which was invisible), which he would later scrape away to raise the seams.31

Danforth also became known for a controversial pick-off move that many felt was a balk. He credited learning his move from an unnamed Cleveland lefty.32 Dave explained:

I noticed that he fooled the runners because he did not kick his leg in the air before he threw the ball to the first baseman. My routine was simple. I’d take a short step, face the batter at the plate with my arm cocked to throw to first base. My left knee would be bent so that I could quickly pivot on it. Then when the unsuspecting runner would take a lead off base, I’d throw the ball and snap my head back to see where it was going.33

Statistician Ernest Lanigan calculated that Danforth led the major leagues in pick-offs in 1916, with 15.34 Roger Bresnahan, who would observe Danforth for many years from the opposing dugout, felt the move was borderline—but legal. “His movement is queer and tricky . . . but I really don’t think it’s a balk movement.”35 Danforth’s move to first base remained contentious for the rest of his career, though it was overshadowed by protests of what he did to the ball.36

Danforth’s 1916 season was fairly ordinary. He appeared in 28 games, 20 of them in relief, with a 6-5 record and a 3.27 earned-run average. With all the controversy swirling around him, teammate Eddie Collins dubbed him “Dauntless Dave.” His White Sox were improving dramatically. After they won 70 games in 1914, new manager Clarence “Pants” Rowland led them to 93 wins in 1915 and 89 in 1916, when they fell just two games short of the pennant.

St. Louis sportswriter J. Roy Stockton wrote about Danforth’s growing fame as a trick pitcher (in what Stockton called the days of the “dodo balls”). Stockton noted that Dave was inquisitive—always warming up in the bullpen, trying out new pitches and perfecting them.37

The 1917 White Sox put it all together. With 100 wins, they won the pennant and beat the New York Giants in the World Series. One of the tools that Rowland employed was the relief pitcher, and Dave Danforth was his man. Dave appeared in 50 games (only 9 starts), 26 finishes, and 9 saves (as computed retroactively), all league-leading numbers.

Typical were a couple of August games. On August 9, Danforth relieved Joe Benz in the sixth and held Washington hitless in a 3-2 win. On August 2, he relieved Red Faber with a 3-1 lead, no outs and the bases loaded in the eighth. Dave snuffed out the rally with a couple of strikeouts and finished a 7-1 White Sox win. (Atypically, the career .160-hitting Danforth hit a bases-clearing triple.)

Also typical were a couple of August incidents. Cleveland manager Lee Fohl declared that if the White Sox won the pennant, they would do so by “unfair tactics,” referring to Danforth’s pitching.38 When Dave pitched six innings of one-run relief to nail down an 8-3 win over the Yankees, they accused him of tossing an emery ball.

The suspicions and charges went beyond Dave Danforth to the White Sox pitching staff as a whole. On August 31, Damon Runyon went public with what had been whispered for weeks. “There is a firm belief among many managers and players in the American League that the success of the White Sox pitchers has been due to trickery –to “monkeying” with the baseball . . . It has been quite openly charged for some time that Commy’s [White Sox owner Charles Comiskey] carvers have been using vaseline and other substances.” Runyon then went further, writing that some players have said that baseballs at White Sox home games were being tampered with. “They claim that a nail file is employed to lift just enough of the seam of the ball to give it a “sailor” [sic] effect when it is thrown.” While Runyon did not completely agree with the charges (they “may or may not be true,” he wrote), he certainly gave them a public platform.39

On August 14, in the second game of a doubleheader, the first pitch Danforth threw in relief hit Cleveland star outfielder Tris Speaker in the right temple and knocked him unconscious for a few minutes. The team doctor said that had the pitch hit an inch lower, “it might have been all up with Spoke.”40 The resultant concussion and blurred vision kept Speaker out of the next seven games. After the incident, he did not speak out against Dave for deliberately throwing a beanball (which he would do three years later when Carl Mays hit Ray Chapman). But Speaker spoke out against the “sailer,” saying that it was time to “call a halt before batting becomes a lost art.”41 He singled out two White Sox hurlers. “The game will go to the dogs unless a stop is put to the doctoring of the ball by [Eddie] Cicotte and Danforth. . . If the Sox win, that is what will give them the pennant.”42 Speaker’s manager was Lee Fohl, who showed a reporter a Danforth-thrown ball, one that had a waxy substance which raised the seams.43 Five years later, Fohl would become Dave’s manager in St. Louis.

The White Sox won four games from the Tigers—two doubleheaders on September 2 and 3, 1917—that would be the focus of a major controversy almost a decade later. Chicago entered the games with a 3 ½ game lead over Boston, which they would stretch to seven games two days later. In late 1926, banned Black Sox player Swede Risberg charged that the Tigers deliberately lost those games and that he helped gather the payoff money that most of the White Sox players —including men considered above reproach, such as Eddie Collins and Ray Schalk–contributed. (The Tigers committed nine errors in those games.) When confronted with the undeniable evidence that they did pay the money, the Chicago players said the money was paid to the Tigers as a token of thanks for their beating the Boston Red Sox three times later that month, September 19-20. Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis did not take any action against the White Sox, other than banning the paying of such “Thank You” money from that point forward.

However, the White Sox’s explanation seemed odd since they had a commanding lead of eight games over Boston on the morning of September 19. More interesting was the fact that only a handful of members of the White Sox did not contribute to the Detroit payoff pool: Manager Rowland, coach Kid Gleason, Eddie Murphy, and Dave Danforth.44 “I didn’t pay a dime toward a pool,” Danforth declared.45

Dave appeared in only one game of the 1917 World Series against the New York Giants. White Sox starters pitched complete games in the first three contests, two of which Chicago won. They were losing Game Four, 3-0, when Dave took over in the eighth inning. He gave up a single to Buck Herzog and a home run to Bennie Kauff. Heinie Zimmerman then tripled but was thrown out trying to steal home, and the Giants won, 5-0. The White Sox then won the fifth game, remembered for Zimmerman’s chase of Eddie Collins. Chicago used four pitchers—but not Dave. A complete-game win by the White Sox’ Red Faber in Game Six won the Series.

Spring training of 1918 was marked by controversy when the respected black trainer of the White Sox, William “Doc” Buckner, was released. The Chicago Defender, the city’s black paper, demanded to know the reason and wondered if Rowland really was running the team “or are some of those southern crackers on the team running it?”46 Chicago sportswriter I. E. Sanborn suggested Dave Danforth was involved. More than five years later, respected Detroit sportswriter H. G. Salsinger elaborated. That spring, Dave had “borrowed” Doc’s sharp scalpel to whittle a piece of wood. When Buckner called Dave down for taking his tool, wrote Salsinger, Dave went after Buckner with a baseball bat.47 Doc Buckner would return to the White Sox in 1920, after Dave had left the team.

Neither Dave nor the White Sox came close to replicating their season in 1918. Dave’s record went from 11-6 to 6-15, with only two saves and a jump of 0.78 in his earned run average. The Sox won less than half of their games and fell to sixth place. Dave did improve in one area: he showed more durability, completing five of the 11 games he started (only one of nine in 1917).

There had been humorous references to Dave and pitcher Lefty Williams as the “50/50 boys,” good half a game each.48 On May 15 and 16, 1918, they belied that moniker. First, Williams went the full 17 1/3 innings in a 1-0 loss to Washington’s Walter Johnson. The next day, Dave pitched 10 2/3 innings of relief in nailing down an extra-inning win. But some things were not changing. Washington manager Clark Griffith (a master of nicking the ball with his spikes when he had pitched three decades earlier) charged Dave with defacing the ball.49

America’s entry into the Great War in 1917 did not have a major impact on American society until the following year. The 1918 major-league season ended a month early as young men from all walks of life were being drafted and sent to Europe. It was not surprising that Dave was not drafted. Not only was he married, but he was supporting his widowed mother (who was living with his family) and his first child, Dorothy, who was born in 1917.

After the shortened 1918 season ended, Dave joined the Baltimore Dry Docks, a powerful semi-pro baseball team. Major leaguers Joe Judge, Wildfire Schulte, and Lefty Russell were also on the club, managed by Dave’s former 1912 Baltimore teammate, Sam Frock. They won 25 of 30 games, including tilts against Chief Bender’s team and independent clubs that had Stan Coveleski and Joe Bush pitching.50

While the White Sox bounced back in 1919, Danforth did not. Hampered by arm trouble, he won only one game, and his earned-run average ballooned to 7.78. On April 25, Dave was shelled by the Browns and didn’t survive the second inning. His July 12 performance epitomized the kind of season he had. He relieved Dickey Kerr in the third inning of a game against the Red Sox. The first pitch he threw was a ball that Babe Ruth knocked out of the park, his first Comiskey Park home run ever.51 Dave went on to give up eight more runs in the game.

On August 26 the White Sox traded him to Columbus of the American Association (which league he had pitched in from 1914 to 1916) in exchange for pitcher Roy Wilkinson.52 Dave brought an action against the White Sox for a World Series share to the National Commission and eventually did receive a one-quarter share.53 One is left to wonder what role, if any, he would have played in the Black Sox scandal.

Danforth refused to report to Columbus and instead went home and again joined the Baltimore Dry Docks.54 They played a best-of-seven series against the powerful Baltimore Orioles of the International League in September. The Orioles’ owner, Jack Dunn, could have prevented Dave from pitching in the Series, but said he wanted the Dry Docks to be at “best strength.”55 The shine ball was not barred either; there were no restrictions on pitches. Finally, Dave had to get permission from Columbus part-owner and general manager Joe Tinker to play in the series. Newspapers reported that Tinker gave it, “under duress.”

Dave led the Dry Docks to the series win with his three victories. He pitched 12.2 innings in the first three games and won the seventh game, 5-0, on one day’s rest, with 15 strikeouts. The Orioles grumbled about his unfair pitches, and one Baltimore paper called him “the Paraffin Kid.”56 The Dry Docks went on to win the national Shipyard Championship, a tourney in which Danforth tossed a 1-0 gem and Red Sox youngster Waite Hoyt pitched a key win.57

In 1920 Danforth joined Columbus, after Tinker persuaded Organized Baseball not to play the Dry Docks again. Both Tinker and manager Derby Day Bill Clymer expressed the belief that Dave had enough “stuff” to win without resorting to the spitter (which had been banned in the league in 1918) or the shine ball.58 Danforth fashioned a 13-12 record with 2.57 earned-run average; he led the league in strikeouts with 188. Once again, his season was not without controversy. In early July he was suspended for “loading up” with a spitter, and he was suspended again a couple of months later.59 When he returned from his suspension, Dave one-hit Milwaukee. In September, Louisville player-manager Joe McCarthy rushed the mound with bat in hand after Dave came close to hitting him twice.60

That fall Clymer moved to the Toledo franchise, and Pants Rowland took over as Columbus manager. He was a big booster of Dave’s. Back in 1919, he said the pitcher had got a raw deal, having been released so close to the World Series.61 The local paper bemoaned the pitching staff of the sixth-place Senators. Other than Danforth, it wrote, the staff “is worth about as much as a German mark in Canada.”62

While the Senators were a very bad team again in 1921—they won only 66 games—Danforth won 25 of them (tied for the league lead in wins). He also led the American Association in strikeouts with 204, earned run average with a 2.66 mark, and complete games, with 35.63 His spectacular season would propel him to the major leagues for the third time. Again, Dave’s work was marked by accusations; it was now that the Columbus Dispatch called him “the icicle of the swirling vortex.”64 Early in the season, his former manager Clymer, now with Toledo, accused Dave of throwing the emery ball and doctoring the ball with his fingernail.65 The “icicle” responded by beating Toledo three times in eight days, by scores of 2-1, 3-0, and 2-0.

St. Louis Browns business manager Bob Quinn had deep Columbus connections, having been born there and run the Senators’ team for a number of years (and managed it back in 1900). He watched Dave three-hit Louisville in the 1921 home opener. As the season developed, it became obvious that the Browns were an offensive powerhouse that was one good pitcher away from seriously contending for the American League pennant. After the season, Columbus manager Rowland began evaluating a number of offers for Dave.66 Somewhat unusual for a minor league club, Rowland was more interested in players than money. This was predicated in no small part on his fear that the major leagues would stop sending players to the minor leagues that had opted out of the draft.67

The Yankees offered $25,000 but could not deliver the players Columbus wanted.68 In mid-December, the Browns stunned the baseball world when they acquired Danforth in exchange for 11 men, in what one paper called “probably the most unique deal ever recorded in baseball.”69 Six men were named; two would be named in 1922, two more in 1923, and one in 1924. They included men with major league experience who were not on the Browns’ roster, men the Browns still had “strings” on.70

The deal generated enormous debate. White Sox manager Kid Gleason, who had dealt a struggling Dave away in 1919, declared, “Anybody who gambles on a left-hander ought to be put in an insane asylum. . . . The three most dangerous things in the world are a four-flush, an unloaded shotgun, and a left-handed pitcher.”71 Dave’s current manager, Pants Rowland, was far more supportive. He explained that Dave’s secret was all in his grip. He told Quinn, “I am not peddling you a lemon. Danforth will make you a pennant contender next year.”72

When Quinn and Browns manager Lee Fohl came under attack for giving up so many men for one, they replied with the “quality versus quantity” argument. “These players aren’t worth a nickel to us and Danforth may ‘make’ us,”73 said Quinn. Fohl went even further. “I have 11 more players who I will be willing to give for any other one pitcher who I believe will help my club.”74

Danforth threw a monkey wrench into the deal as spring training approached. He demanded 10 percent of the cash value of the players that Columbus had received before he would sign his contract. After a short period of time, after getting an ultimatum from his manager to report “or else,” he did sign and report.75 A newspaper in Mobile, Alabama, where the Browns were training, declared, “If he [Danforth] flashes, it means the flag.”76

Early in the season the Browns were in or around first place, a preview of a hard-fought pennant race with the Yankees that would continue all season long. Lee Fohl did not put Danforth in the regular rotation because his presence on the mound generated so much controversy and because Fohl himself became concerned that Dave was indeed doctoring the ball. Accusations dogged Dave from the start of the season. His nemesis, Ty Cobb, protested Danforth’s delivery in an early-season series and declared that he would expose Dave.77 During a mid-June complete-game win over the Yankees, New York repeatedly questioned the baseballs he threw. Umpire Billy Evans, behind home plate that day, felt that Dave had pitched a “clean-cut game.”78

Evans’s role in the Danforth controversy over the years is fascinating. The respected Hall of Fame umpire was one of the few arbiters of the game who felt Dave was not tampering with the ball. He was also the only umpire who occasionally spoke out on Dave’s behalf. When Danforth joined the White Sox, Evans had been fascinated by his “newfangled mystery ball.”79 Before the deal with Columbus, Evans had assured Bob Quinn that Dave’s delivery was clean.80 In early July 1922, Evans commented on Danforth’s “heart,” for having the fortitude to keep coming back in the face of constant accusations.81 In one of his columns, Evans listed all the things Dave had been accused of doing—from loading the seams to loosening the cover to roughening the ball with his fingernail—and then declared, “None of these things were ever proved.”82 His use of the “Dauntless Dave” moniker certainly seemed appropriate.

While the constant protestations may have been aggravating to Danforth, he also took some comfort in the fact that his reputation had batters so worked up that they may have diverted their focus from something more important: hitting the ball. Dave said that he modeled himself on the great lefthander, Eddie Plank. Plank fidgeted and delayed so much on the mound that he had opposing batters seeing red. “Get the batter nervous, and you have him down,” Dave told the St. Louis Times that spring.83

Matters finally came to a head on July 27, 1922. In the tenth inning of a tie game against the Yankees, Danforth threw a pitch that sailed in on Fred Hofmann. Dave was ejected by umpire Brick Owens for throwing a ball with loaded seams (though Dave had just entered the game). An automatic ten-game suspension followed. Business manager Quinn had already gone on the record back in May that he’d release Dave if the charges proved true.84 He and Lee Fohl were coming to the joint conclusion that the pitcher they had paid so dearly for was not “clean.”

The stories of just what Danforth did to the ball swirled around him, and they were all across the board. He was said to have a nail on his left thumb that was so sharp that he could slit the seams or so rough that he could make an abrasion on the ball. He was reputed to sleep with his pitching hand soaking in a tray of pickle brine, to make his skin as abrasive as emery paper and let him roughen up the ball. He was also accused of using his large and powerful hands to loosen the cover of the ball.85

In early August, the Browns put Dave on waivers, and not a single team claimed him. Veteran St. Louis sportswriter John Wray was moved to write, “Dave was either unanimously voted of little value, or a tacit agreement to ‘railroad’ him for the good of the game had taken effect.”86 The next day, the usually taciturn Danforth made a lengthy statement to the Post-Dispatch. He said that he had never loaded the seams of a ball or applied a foreign substance to it. He bemoaned the “continual nagging” by umpires because of “adverse publicity.” He admitted to rubbing the ball with his hands, but noted that was legal. If that was to be deemed illegal, “then I am guilty of illegal pitching and every other pitcher in baseball is equally guilty.”87

The Browns sent Dave to Tulsa of the Western League (with an option to recall him), a lower classification league than the one Columbus was in. Like the Browns, the Oilers were in a pennant race, and Danforth’s six victories helped them win the pennant. On August 26, he struck out 15 men, breaking Dan Tipple’s league record of 14, set earlier that year. On September 15, the Oilers won their 100th game as Dave three-hit Oklahoma City.88

The Oilers then met the Mobile Bears of the Southern Association for the Class A championship. In Game Four, a victory for Dave, more than 25 balls were removed from play, as Mobile protested. The Tulsa World said, “The fact that the ball was faulty does not mean that Danforth had made it so.”89 Dave also won Game Six with a shutout, and the championship belonged to Tulsa.

The St. Louis Browns were not as fortunate. They lost the pennant by just one game to the Yankees. Had Danforth stayed with them during the stretch run, they would have had a good chance to finish in first place. A couple of weeks after the season, the Browns recalled Danforth for 1923. Owner Phil Ball had overruled his management team; neither Quinn nor Fohl wanted Danforth back. Fohl told a reporter that Dave had been given more chances to go straight (or throw straight) than he deserved.90

A pall was cast over the Browns’ 1923 season when George Sisler was forced to sit out the year, with a serious eye injury. Danforth became a mainstay of the Browns’ pitching staff, along with Urban Shocker and Elam Vangilder. This would be the first of three seasons in which he would appear in an average of 39 games and toss more than 200 innings a year.

Controversy still shadowed Danforth. The season started with Ty Cobb again protesting his delivery on April 18, and a suspicious ball was forwarded to league President Ban Johnson.91 Still Dave persevered, and on April 29 he pitched one of his finest games in the major leagues. He dropped a 1-0 game to those same Tigers (Cobb was hitless), giving up the lone run in the ninth inning.

On August 1, in a game against the Athletics, with umpire George Moriarty calling balls and strikes, Danforth was ejected for throwing a ball with rough spots on it. His former teammate on the 1916 Chicago White Sox, Moriarty had been a teammate of Ty Cobb’s for many years. He and Dave had a long-running feud, the source of which remains unknown. Years later, Danforth said that he wished Moriarty had not tried to ride him so hard. “He calls me names and abuses me,” all the time. In one game, Danforth said, when Moriarty called him from the bullpen, he said, “Hurry up there, you cheating _____. You’ve never done anything in your life but cheat.”92

Yet it wasn’t just Moriarty who questioned Danforth’s pitches. When this latest controversy broke, St. Louis Times sports editor Sid Keener wrote, “I have talked with almost every umpire in the American League on the charge against Danforth. The report from them is unanimous—that Dave applies a foreign substance or otherwise tampers with the ball.”93

Danforth’s teammates rallied to his side. Outfielder Johnny Tobin said that Dave had a grip that was “out of this world.”94 Dave’s catcher, veteran Hank Severeid said, “A pitcher can’t fool his own catcher. And I am certain Dave has not employed illegal methods.”95 George Sisler, who would become Dave’s manager in 1924 and 1925, told Baseball magazine, “In all the time he has played with us, I have never known Dave Danforth to use any illegal delivery. . . . If he does things with a ball that other pitchers can’t do, that is no proof of illegal delivery. . . . Danforth is a high grade fellow in every way and he deserves the right to work at his profession without being molested.”96

Danforth’s teammates even put together a petition to send to league president Ban Johnson. But one person would not sign it; one man would not rally to Dave’s support: the team’s soft-spoken manager, Lee Fohl. Bob Quinn had already left the Browns, partly in frustration over working with owner Ball and partly for an opportunity to head the group that bought the Boston Red Sox from Harry Frazee. Fohl met with Sid Keener and showed him some balls that he said Dave had tampered with. All were new balls that had a rough spot of about two inches square. Keener went public with this evidence (including diagrams of the balls) a few weeks later.97

Keener weighed in on the controversy. “I know the character of Lee Fohl. He would give a friend the last dime he had in the world. . . . If Lee wouldn’t sign [the petition] there must be some black smoke in the air.”98 When the dust settled a few days later, Fohl had been fired by a furious owner. Phil Ball felt he had gone to great lengths and cost to secure Dave, only to be undercut by a manager who refused to use the talent he was provided.

While Danforth was serving his automatic ten-game suspension, Ban Johnson weighed in on the matter. A close confidant of Phil Ball, Johnson did not agree with Ball in this matter. Supporting Lee Fohl, Johnson said that Dave had a “mania” for doctoring the ball and was “incurable” as an illegal pitcher.99

On August 16, 1923, with both Ban Johnson and Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis in the stands, Dave returned to the mound. He was facing the league-leading Yankees in St. Louis. He understood that his career would end if he resorted to trick pitches. With Billy Evans behind the plate, Dave decided to remove any suspicions by constantly asking for a new baseball, whenever the ball became discolored or marked up in any way. An incredible 58 balls were put in play, and still Dave was effective. He threw a three-hitter, though the Yankees’ Herb Pennock was better yet, and the Yankees came out on top, 3-1.

Danforth lost the game, but he won over a lot of hearts on that day. Sid Keener saluted him, writing, “It was a game that only a steel heart and a concrete spine could have pitched. Considering all events in the case I have never seen its equal on the ball field.”100 It was this performance that prompted J. Roy Stockton to write the quote that introduces this biography. It was also the culmination of more than a year that Dave had been under the microscope, leading Baseball magazine’s F. C. Lane to declare, “His [Danforth’s] work on the pitching mound has been more carefully scrutinized and more universally criticized than that of any pitcher on record, not excepting the ill-omened [Carl] Mays.”101

The monthly magazine even weighed in with an editorial, wondering why the Danforth controversy could not be resolved:

“Danforth doesn’t mutter incantations over the baseball in the dark of the moon near a convenient graveyard with the accompaniment of bats’ wings and rabbits’ feet. What he does if anything, he does in the full view of lynx-eyed umpires and ballplayers and the ball itself that he handles is evidence pro or con. Why not clear up the Danforth mystery once and for all?”102

If only it were so easy . . .

Dave finished the 1923 season with the most wins (16), innings pitched (226 1/3), complete games (16), and strikeouts (96) in his major-league career. He did hit 12 batters and had a 3.94 earned-run average, slightly better than the league average of 3.98.103

In 1924, Danforth posted numbers close to those of ’23 in wins (15), innings pitched (219 2/3), and complete games (12), but his earned-run average rose to 4.51. An anomaly was that he gave up 16 home runs that year (one behind the league leader); he had never given up more than four in a season. The clamor over Danforth’s delivery subsided. After he beat the White Sox on May 30, Chicago sportswriter James Crusinberry wrote that Dave was “a real pitcher and always was one and the accusations against him were the bunk.”104 Subsided, but not disappeared. Player-managers Ty Cobb and Eddie Collins contacted Ban Johnson and requested that umpires watch Danforth closely. Johnson wrote to Browns player-manager George Sisler that if Dave was using his “sandpapered” hand on the ball, he should discontinue doing so at once.105 When Danforth shut out the Yankees on June 8—one of only two career shutouts—Miller Huggins complained that his thumb nail was loosening the cover and that he was throwing the spitter.106

When Dave three-hit the Tigers on July 6, he had to do it with Ty Cobb constantly heckling and accusing him of pitching illegally. At that point in the season, Danforth’s record stood at 10-4. He cooled off from then on, finishing at 15-12. On August 5 he and Urban Shocker swept a pair of games against Washington to draw the Browns within four games of first place, though fourth place was where they would finish the season.

Danforth’s final season in the major leagues was 1925. He held out and signed a contract for the same amount of money he got in 1925, $6,500.107 His record was a pedestrian 7-9, and he led the league in giving up home runs, with 19. On May 6 he gave up a home run to his nemesis, Ty Cobb, one of five Cobb hit in two consecutive games in St. Louis.

Approaching the age of 36, Danforth seemed to be near the end of his baseball life. Yet he was about to embark on another minor league career, one that would include remarkable team and personal achievements. After he left the Browns, a Sporting News columnist admired Dave’s courage and declared, “Whether he is a cheater or a wizard we are willing to admit Dave has won his point. More power to him.”108

Danforth came to the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association in 1926, as part of a deal that sent Oscar Melillo to the Browns. Dave won 17 games and threw 273 innings in 43 games. In late May and early June, he helped fuel the Brewers 21-game winning streak, a new league record. Dave won the 10th and 20th games of that streak. Ironically, early in the year, the fans and press had been critical of owner Otto Borchert for making a six-figure annual profit and not putting enough money back into his club. The Milwaukee Sentinel had called him out for “pursuing a niggardly nickel-nursing policy.”109

Early in the 1927 season, after Danforth pitched poorly in a few games, the Brewers sold him to New Orleans. His 16-4 record and sparkling 2.24 earned run average helped lead the Pelicans to the Southern Association pennant. When he was hit hard in early June, the New Orleans Times-Picayune noted that if Dave had anything foreign on the ball, “the [Memphis] Chicks knocked it off.”110 That comment served as a reminder of something that Danforth would point out over the years, words that would also show up in many of his obituaries. “You never heard a squawk on my bad days.”111

Dave hit a groove as the summer began, with a couple of two-hitters and two four-hitters among his wins. He also had the best control of his career (only 28 walks in 181 innings). The Times-Picayune noted that he went 41 innings without giving up a walk.112 After he was tossed out of a game for supposedly rubbing dirt into the seams of a ball, Danforth said, “I have been hounded most of my baseball career by umpires who seemed to be seeking publicity at my expense.”113 His Pelicans manager, Larry Gilbert, said, “I never learned what he did—if he did anything. I know he wanted the batters to think so.”114

The Pelicans were swept in the Dixie Series by Wichita Falls of the Texas League, in four straight games. Dave pitched well but lost two of the games, as the Pelicans generated little offense.

In 1928, neither Danforth nor the Pelicans could replicate their 1927 performances. Dave fashioned a 10-11 record, and his earned-run average more than doubled to 4.71. Somewhat surprisingly, he was named to the league’s all-star team. The Pelicans finished in third place. In 1929 Dave bounced back (8-7, 3.39), but the 38-year-old missed three weeks in August with a strained back.

Danforth was sent to Dallas in December, 1929, in a trade for former major-league pitcher Whitey Glazner.115 The biggest controversy revolved around something other than Dave for a change: radio. Dallas fans were upset that the league banned broadcasts and boycotted early games. (Only 9,000 attended the home opener.) The owners finally relented and allowed broadcasts of road games.116 The other big event in Dallas was the signing of Grover Cleveland Alexander, after his major-league career had ended. Neither pitcher was effective: Alexander won only one game before being released, and Danforth won only two. Dave was released in early July, after which an unnamed teammate said Danforth kept his glove oiled, so it would accumulate dust that Dave would grind into the ball.117

At the age of 40, Dave managed to catch on with Buffalo of the International League, a higher (Double A) league than the Southern Association (A). He immediately found himself in the spotlight, quite literally. On July 3, he pitched the International League’s first night baseball game with permanent lighting (what were called “arc lights,” 24,000 watts of them), a month after the first such minor league game was played.118 Dave struck out ten but lost to Montreal, 5-4. He was accused of trick pitching and almost came to blows with Montreal manager Ed Holly. Years later, Danforth’s player-manager on the Bisons that year, Jimmy Cooney, said that Dave had a little black bag that he kept locked at all times.119

Danforth won 12 of 20 decisions for Buffalo in 1930, and none was bigger than the one in which he beat Rochester on September 20. He struck out 20 Rochester Red Wings, including their player-manager, Billy Southworth, four times.120 In doing so, Danforth set an International League record, breaking the record of 17 set by Lefty Grove of Baltimore and Leroy Herrmann of Reading. The current International League record of 22 was set by Bob Veale on August 10, 1962.121

Danforth started the 1931 season with the Bisons, but with a 3-6 record and 6.45 earned run average in 14 games, they sent him to Chattanooga of the Southern Association on July 15. When he tossed his second shutout in ten days, the Chattanooga paper featured “Dauntless Dave, the suspicious southpaw.”122 At the end of the season, after he won four of ten decisions, Chattanooga returned him to Buffalo.123

The 42-year-old pitcher had a young teammate by the name of Billy Werber. In 2001, the 93-year-old Werber immediately recalled Dave. He told the author, “Danforth, he was a lefty. A gentlemanly type . . . a quiet fellow. Never had a hell of a lot to say. . . . Dave didn’t have the disposition to do anything illegal with the ball.”124

Danforth was released in mid-May 1932, after a few ineffective outings, in which he was hit hard. He managed to hook up with Bill Clymer’s Scranton Miners of the New York-Penn League, a lower-tier (B) league. Clymer probably did a favor for Dave, whom he managed in Columbus (1920) and Buffalo in 1930. After appearing in only six games, Dave was released. His professional career was over.125

Dave drew on his degree of almost 20 years earlier and began to practice dentistry in his hometown of Baltimore. He would do so until 1960, when he turned 70. He had returned to the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery for postgraduate review back in 1927.126 Danforth also taught “operative dentistry” at the University of Maryland twice a week for a number of years. “I haven’t gotten as far in it [dentistry] as I did in baseball, nor does it appeal to me as baseball did.”127 Dave coached the Loyola College baseball team in 1937 and 1938.128 In 1939, he returned to Shibe Park for an old-timers’ game, in which the Athletics of 1910-1914 beat the A’s of 1929-1931.129 He also attended a Buffalo Bisons old-timers’ reunion game on August 21, 1964.130

Two days after the death of Joe Jackson, on December 7, 1951, Danforth wrote a condolence letter to the family of his former teammate. “He was underpaid and criticized and punished beyond reason. He was a fine man,” Dave wrote.131

Dave did not attend professional baseball games, despite receiving a lifetime pass from the Orioles.132 He enjoyed golf, fishing, and gardening. He suffered from Alzheimer’s disease the end of his life and died at the age of 80 on September 19, 1970 in Baltimore.

*****

Dave’s scientific approach to pitching was years ahead of his time. In a 1926 Baseball magazine article entitled “Why Pitching is in its Infancy,” he said, “Pitching twenty or thirty years from now will be much more complex than it is today. . . . No Major League club manager, scout, or anyone else, has any clear idea of just what the human hand can do with a baseball.” He noted that physics and math experts have not determined just what could be done with a baseball. The magazine wrote that Dave’s “enquiring mind” and “restless spirit of investigation” have led to his constant experimentation with pitches and deliveries.133

Danforth often said that there was no secret to his pitching, “just psychology and a good fast ball.” He went on to explain, “There’s no rule against rubbing a ball with your hands. Often I did it deliberately a long time for psychological effect.”134 But there was also Dave’s admission, “I will admit that in my time I have used every delivery that I ever heard of. If I had known of any others I should have used them.”135 Jim Bagby, Cleveland pitcher of the 1920s, said that he knew what Dave did—and said it was not illegal. “You see he had such a tremendous grip he could ruffle up that cover.”136

Danforth’s grandson, Rob Harmon, recalled that his grandfather was the strongest man he ever knew. He remembered Dave at the age of 70 lifting a tree stump out of the ground and shimmying up a tree during a storm. Rob remembered that when he was 11 or 12, Dave showed him how he could do something to a baseball. With his large and powerful hands, Dave gave the ball a jerk, or twist, to misshape it, stretch the cover, and raise the seams.137

If indeed Danforth simply used his own hands and grip (and not a rough fingernail or roughened skin to doctor the ball), would that have been illegal? Under Rule 14, Section 4, “Discolored or Damaged Balls” [Section 2, Rule 30] of the baseball rules, as stated in the 1921 Spalding Guide,

In the event of the ball being intentionally discolored by any player, either by rubbing it with the soil, or by applying rosin, paraffin, licorice, or any other foreign substance to it, or otherwise intentionally damaging or roughening the same with sand-paper or emery-paper or other substance, the umpire shall forthwith demand the return of that ball, and substitute for it another legal ball, and the offending player shall be debarred from further participating in the game. If, however, the umpire cannot determine the violator of this rule, and the ball is delivered to the bat by the pitcher, then the latter shall be at once removed from the game, and as an additional penalty shall be automatically suspended for a period of ten days.138

While an abrasive fingernail or skin probably falls under “other substance” mentioned above, what about powerful hands? Even if it does not, the end of this rule states that the pitcher is held responsible even if the umpire cannot determine who defaced the ball.

Longtime Hearst sportswriter G. Frank Menke wrote, “Danforth is a great pitcher and might have been one of baseball’s greatest . . . had he not been cursed with the suspicions of illegally tampering with the ball.”139 No one ever caught Dave; “they convicted him on suspicion.”140 Yet Danforth really brought on that suspicion, as part of his “mind games” with batters. And he put umpires in a difficult position. Sportswriter Fred Turbyville provided some perspective from the men in blue. He noted that umpires hated rows, and whenever Dave pitched, there were rows. “David was a crucifix for umpires.”141

New York sportswriter Tom Meany may have provided insight into Dave’s pitching style and approach. “It seemed that Danforth was not only a pitcher but a practical psychologist as well. Nobody ever saw the left hand which was supposed to be so ruinous to the surface of a baseball. . . . Batters who are always seeking to detect some sign of chicanery on a pitcher’s part sometimes become so engrossed in looking for illegal pitches that they forget to hit the legal ones.”142

Notes

1 Columbus Dispatch, June 2, 1921.

2 Hugh Bradley, “Freak Pitching Deliveries—Past and Present,” Baseball magazine, June 1936.

3 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 19, 1923.

4 In the 1880 census, Charles is listed as a farmer. Henrietta and her parents were born in Germany, as listed in the 1890 Census.

5 Listed in the 1880 Census as Prussia.

6 Email from Lajuna Danforth Carabasi, Dave’s niece, to the author, dated April 5, 2011.

7 Undated Philadelphia newspaper clipping, Danforth family scrapbook,

8 Atlanta Constitution, August 9, 1911.

9 Washington Post, August 10, 1911; Charlotte Observer, September 6, 1911.

10 The Sporting News, May 16, 1912.

11 Philadelphia Evening Ledger, August 31, 1917; Lexington Herald, October 18, 1917.

12 Hall of Fame contract card suggests it was an outright sale in May, but Baltimore accounts suggest Connie didn’t give up his claim to Dave until that August deal, Most reports said Mack gave up Claud Derrick and Bris Lord, and cash for Walsh and Murphy.

13 Shawkey led the way with 17 wins; Dave won 12 games. Vickers won 13; he had won 57 games for the 1910-1911 Orioles.

14 E-mail from Jim Thompson to author.

15 Hall of Fame contract card. Red Sox scout and former Red Sox manager Patsy Donovan said that he was sent to Baltimore to scout Dave and to decide whether the Red Sox should purchase him. Instead, Donovan was so impressed by Ruth and Ernie Shore that he told Boston owner Joe Lannin to buy Ruth and Shore instead.

16 Newspaper clipping, Danforth family scrapbook; Baltimore Sun, December 11, 1914.

17 Louisville Courier, August 7, 1915.

18 Danforth obituary, New York Times, September 22, 1970.

19 O’Toole was with St. Paul and set the mark against Milwaukee on July 10, 1911. There was also mention that Danforth broke Willie Mitchell’s two-game mark of 32 strikeouts, set in 1909 with San Antonio. Fort Worth Star-Telegram, October 15, 1915.

20 Some accounts say that Dave struck out 16 in that game.

21 American Association historian Marshall Wright confirms these strikeout records. As stunning as was McDermott’s game, he followed it in his next four games with a string of 19, 18, 17, and 19 strikeouts. McDermott’s Wikipedia entry, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mickey_McDermott.

22 Hartford Courant, September 2, 1923.

23 New York Times, September 28, 1919.

24 “Why Dave Danforth has been a Storm Center,” Baseball magazine, July 1924.

25 Don Basenfelder manuscript, Sporting News files.

26 The Sporting News, April 20, 1916.

27 Baltimore Sun, December 20, 1915.

28 The Sporting News, October 7, 1915. In the next few years, there would be much debate over the shine ball, with many suggesting it didn’t really exist, that Eddie Cicotte simply led people to believe he was doing something with the ball. The Minneapolis players were spot-on with their analysis.

29 Daily Morning Oregonian, April 27, 1917.

30 The Sporting News, April 20, 1916.

31 New York Evening Journal, January 23, 1924.

32 Dave did not say what year he learned the move. It could have been during his brief stint with the Athletics. More likely, he was referring to a pitcher on the American Association’s Cleveland franchise, known as the Bearcats in 1914 and the Spiders in 1915.

33 Don Basenfelder manuscript, Sporting News files.

34 Newspaper clipping, Danforth family scrapbook.

35 Wilkes-Barre Times-Leader, January 19, 1922.

36 Dave was called for a balk 13 times in his major-league career, with seven of them in 1922-1923.

37 J. Roy Stockton, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, undated 1917 newspaper clipping, Danforth family scrapbook.

38 Wilkes-Barre Times-Leader, August 14, 1917.

39 New York American, July 31, 1917.

40 Charles Alexander, Spoke. p. 121. Dave was not known as a “headhunter.” He hit only three batsmen in 1916, and the same number in 1917. Carl Mays hit 9 and 14, respectively, those years.

41 Ibid. While a “sailer” was assumed to have resulted from doctoring the ball in this era, former major-league pitcher Dave Baldwin explained to the author that this effect is generated nowadays from the cut fastball (gripped slightly off-center). E-mail to the author, March 31, 2011.

42 New York Tribune, August 26, 1917.

43 Ibid.

44 Danforth pitched briefly in three of the games. In two, he snuffed out rallies and was pulled for pinch hitters in the bottom of the first inning in which he appeared. In the third game, he was not as effective.

45 Daily Boston Globe, January 2, 1927.

46 Chicago Defender, March 23, 1918.

47 Washington Post, September 19, 1923. Salsinger brought this up after Dave was the center of another controversy, one that had cost his manager his job.

48 Fort Wayne News-Sentinel, May 7, 1918. In his first two seasons with Chicago, 1916-1917, Williams started 55 games and finished only 18, a completion rate below those of the average starter in those seasons, which was slightly more than 50 percent.

49 Washington Post, May 17, 1918. Three years later, Griffith would offer $50,000 in an unsuccessful attempt to acquire Dave. Washington Post, December 9, 1921.

50 The Baltimore Evening Sun gave good accounts of the Dry Docks of 1918-1919.

51 It was Ruth’s 11th home run of 1919 and the 31st of his career.

52 Wilkinson had won 17 games with a 2.08 earned run average for Columbus. He would win only 12 games in the majors, and had a 4-20 record for the 1921 White Sox. The Chicago Daily Journal noted that the White Sox also included cash in the deal, a reflection of how far Danforth’s stock had fallen. August 26, 1919.

53 E-mail from historian Gene Carney to the author, dated October 22, 2003.

54 Danforth’s Hall of Fame contract card shows that he was suspended for this action and later reinstated, when the 1920 season approached. The International League champions did not play the American Association champion in the Little World Series that year. Instead, the AA’s St. Paul Saints met the Pacific Coast League champion, and the Orioles were available to play the Dry Docks.

55 Newspaper clipping, Danforth family scrapbook. Jack Dunn was close to Joe Tinker, which probably explains the latter’s granting Dave clearance to play.

56 Baltimore Evening Sun, September 26, 1919.

57 Jimmy Keenan, Lefty Russell BioProject biography, http://bioproj.sabr.org/

58 Daily Morning Oregonian, March 14, 1920.

59 Kansas City Times, July 2, 1920; Columbus Dispatch, September 14, 1920. Each infraction resulted in an automatic ten-day suspension.

60 Kansas City Times, September 14, 1920.

61 Newspaper clipping, Danforth family scrapbook.

62 Columbus Dispatch, December 11-12, 1920.

63 Danforth’s league-leading figures for 1920 (strikeouts) and 1921 are from The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Third Edition, edited by Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff.

64 Columbus Dispatch, June 2, 1921.

65 Ohio State Journal (Columbus, Ohio), May 1, 1921.

66 By now, Joe Tinker had sold his interest in the team and moved with his sick wife to Florida. The American Association was also one of the minor leagues that had “opted out” of the draft. This was an excellent example of why they did so: Rather than lose a star like Dave in the draft for a nominal fee, they could wheel and deal with a number of clubs and extract a higher price or a number of players.

67 New York Herald, December 15, 1921.

68 St. Louis Times, March 15, 1922; Columbus Dispatch, December 15, 1921.

69 Newspaper clipping, Dave Danforth scrapbook.

70 For example, Grover Lowdermilk had pitched in the major leagues for parts of nine seasons and was currently on the Minneapolis roster. Emilio Palmero had pitched briefly for the Browns in 1921 and was recalled from Louisville.

71 Columbus Dispatch, January 1, 1922.

72 St. Louis Times, December 15, 1921.

73 New York American, December 15, 1921.

74 George Robinson, “Dave Danforth, Devious Dentist,” unpublished paper, April 2011.

75 Since there was no cash involved, there would have had to be a cash figure assigned to the players’ values. There were reports that the deal would have translated to a cash value of $75,000-$90,000, which seems high. Since St. Louis and not Columbus needed to mollify Danforth (the latter already had their deal, regardless of whether Dave would report), it is likely a compromise figure was reached and paid by the Browns.

76 Mobile Register, March 19, 1922.

77 Kansas City Star, April 26, 1922; New York Globe and Commercial Advertiser, April 28, 1922. The Tigers had been tipped off by veteran White Sox catcher Billy Sullivan, who was now a Detroit coach. Sullivan had observed Dave while playing for the Minneapolis Millers in 1915. Chicago Daily Tribune, April 22, 1916. See endnote 28.

78 St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 14, 1922.

79 Morning Daily Oregonian, January 15, 1916.

80# Columbus Dispatch, January 13, 1922.

81 San Jose Evening News, July 7, 1922.

82 Newspaper clipping, Danforth family scrapbook.

83 St. Louis Times, March 4, 1922 and March 15, 1922. Apparently Danforth sought out Plank, his old Philadelphia teammate, when he returned to the major leagues in 1916. Wilkes-Barre Times-Leader, June 19, 1922.

84 St. Louis Times, May 15, 1922. The Yankees rallied to win that July 27 game in extra innings and closed to within one game of the first-place Browns.

85 Basenfelder manuscript and an undated Sporting News article, conveyed by historian Norman Macht, said that Danforth did so. Dave’s son-in-law, Jim Thompson, told the author that Dave did indeed soak his hand in brine, but not overnight. Dave’s daughter Jean Danforth Thompson said to the author he also used the fluid that is used on violin bows on his hand. Phone conversations with the author, January 6, 2002.

86 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 12, 1922.

87 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 13, 1922.

88 Tulsa World, August 27, 1922 and September 16, 1922.

89 Tulsa World, September 30, 1922.

90 Martin J. Haley, St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 20, 1922.

91 Marc Okkonen, Ty Cobb Scrapbook, p. 172.

92 Washington Post, April 30, 1925.

93 St. Louis Times, August 3, 1923. One wonders if Keener spoke with Billy Evans and, if he did, what the umpire told him.

94 Roger Godin, The 1922 St. Louis Browns: Best of the American League’s Worst.

95 Don Basenfelder manuscript, Sporting News files.

96 “Why Dave Danforth has been a Storm Center,” Baseball magazine, July 1924.

97 St. Louis Times, August 22, 1923.

98 St. Louis Times, August 3, 1923.

99 St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 15, 1923 and New York Times, August 15, 1923.

100 St. Louis Times, August 17, 1923.

101 “Why Dave Danforth has been a Storm Center,” Baseball magazine, July 1924.

102 Baseball magazine, October 1923.

103 Other than 1923, Dave never hit more than five batters (1918). His 12 hit batsmen would have led the National League in 1923, but Howard Ehmke and Walter Johnson hit 20 men in the American League.

104 Chicago Daily Tribune, May 31, 1924.

105 June 3, 1924 letter, American League Archives, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

106 New York Telegram and Evening Mail, June 9, 1924; St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 13, 1924.

107 National Baseball Hall of Fame contract cards. This was the highest salary Dave earned.

108 “Scribbled by Scribes,” The Sporting News, July 15, 1926.

109 Milwaukee Sentinel, March 19, 1926.

110 New Orleans Times-Picayune, June 6, 1927.

111 Chicago Daily Tribune, March 24, 1944.

112 New Orleans Times-Picayune, July 2, 1927.

113 New Orleans Times-Picayune, August 29, 1927.

114 Atlanta Constitution, March 13, 1937.

115 Atlanta Constitution, December 6, 1929. Glazner had a 15-9 record for Dallas in 1929 and then went 19-8 for New Orleans in 1930.

116 Dallas News, April 15, 1930 and May 3, 1930.

117 Dallas News, July 6, 1930.

118 On May 2, 1930, a Western League game in Des Moines (played at night against Wichita) drew 12,000 fans for a team that was averaging 600. www.minorleaguebaseball.com/milb/history/timeline.jsp.

119 Buffalo Evening News, August 1, 1964.

120 Southworth was one of the toughest men to strike out in major-league baseball history. He ranks number 26 on the all-time list, whiffing only once every 29.45 at bats. www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/at_bats_per_strikeout_career.shtml.

121 Albany pitcher Cy Blanton tied the mark on September 1, 1934. New York Times, September 2, 1934. Veale set his record with the Columbus Jets, against the Buffalo Bisons. It was a 12-inning game, but Veale was removed for a pinch hitter in the tenth inning and pitched only nine innings.

122 Chattanooga Times, August 22, 1931.

123 “Returned” is the word on the Danforth transaction card at the Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

124 Telephone interview with the author, July 11, 2001.

125 There was mention that Dave joined Pine Bluff (Arkansas) of the D-level Cotton States League. Atlanta Constitution, May 22, 1932. Baseball-reference.com lists “Danforth?” on that team and lists his 1932 record as 11-5.

126 Danforth family scrapbook.

127 Undated Danforth letter in Danforth family scrapbook.

128 Hartford Courant, May 2, 1937, and March 16, 1938.

129 Daily Boston Globe, September 11, 1939.

130 Buffalo Evening News, August 16, 1964.

131 Letter of Dave Danforth, Mastro Auction, August 31, 2007.

132 Dave’s daughter, Elaine Danforth Harmon, was probably referring to the major-league Baltimore Orioles, who began operating there in 1954.

133 “Why Pitching is in its Infancy,” Baseball magazine, February 1926.

134 Chicago Daily Tribune, March 24, 1944.

135 “Why Dave Danforth has been a Storm Center,” Baseball magazine, July 1924.

136 Atlanta Constitution, March 31, 1940.

137 Phone conversation with the author, January 25, 2002.

138 Rule 30, Section 2 elaborates: “At no time during the progress of the game shall the pitcher be allowed to (1) apply a foreign substance to the ball . . . (4) deface the ball in any manner.”

139 Quoted in Journal of the American Dental Association, November, 1967.

140 Ralph McGill, Atlanta Constitution, July 17, 1931.

141 Fred Turbyville, undated Evening Star newspaper clipping in Danforth family scrapbook. Detroit sportswriter H. G. Salsinger supported this line of thinking when he wrote, “Umpires felt like resigning whenever Danforth warmed up, for it meant another tough afternoon for them.” Detroit News, April 19, 1923.

142 Tom Meany, Baseball’s Greatest Teams, p. 197.

Full Name

David Charles Danforth

Born

March 7, 1890 at Granger, TX (USA)

Died

September 19, 1970 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.