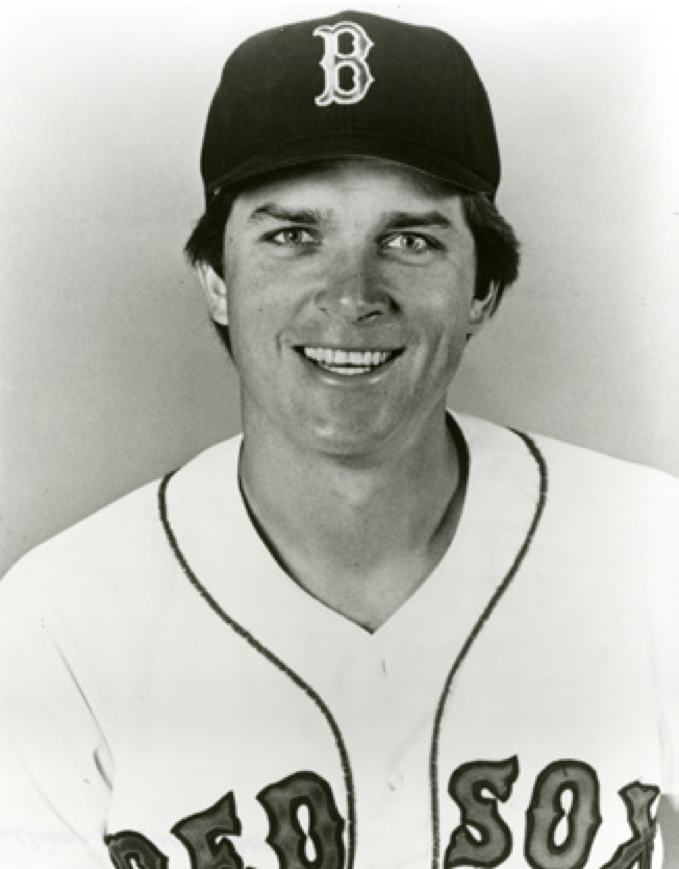

Marc Sullivan

Marc Sullivan started 35 games in 1986 as backup to All-Star catcher Rich Gedman. He made the squad in spring training because of his defensive skills, but many critical Red Sox fans and beat writers would not overlook his offensive shortcomings. He hit only .193, with 23 hits in 119 at-bats, and seemed to be booed more rabidly than other Red Sox players when he struck out or failed to advance a baserunner. A common assumption was that Sullivan was on the team only because his father, Haywood Sullivan, was the team’s general manager and part owner. Toward the end of spring training the Boston Globe’s Dan Shaughnessy expressed the view of many when he wrote that “Marc Sullivan is hitting .167 and is assumed to have the backup catcher’s job because of his defensive ability (he’s also the owner’s son and makes $110,000.)”1

Sullivan started only two games in April, but manager John McNamara came to his defense. “He’s not here because he’s the owner’s son,” McNamara said. “He comes in with a shadow cast over him because of who he is, but he’s a good catcher. We had a lot of interest in him [from other teams in the offseason.”2

The Red Sox surprised a lot of baseball fans and experts when they drafted Marc Sullivan in the second round (52nd overall) of the 1979 June amateur draft. (Boston lost its first-round pick to Oakland when it signed free-agent pitcher Steve Renko in January.) Although Sullivan grew up playing catch with Red Sox players like Carlton Fisk and Carl Yastrzemski, and had Fenway Park and the team’s spring-training camp in Winter Haven, Florida, as playgrounds, his own baseball credentials had not been impressive.

He played on youth baseball teams, regularly attended the prestigious Ted Williams Camp in Lakeville, Massachusetts, and was a two-sport star — basketball and baseball — at Canton (Massachusetts) High School. Marc Cooper Sullivan had been born in Quincy, Massachusetts, just south of Boston, on July 25, 1958, when his father was a catcher for the Red Sox. Haywood had been a top catching prospect and signed an estimated $40,000 to 50,000 bonus contract with the Red Sox after the 1952 season. The Canton High baseball team played only 15 or 20 games a year, and Marc was listed as an infielder when he signed a grant-in-aid to play baseball at the University of Florida in July 1976.3 He was following his father to Florida, where Haywood had starred in football and baseball.

Catching wasn’t even Marc’s favorite position. “But when it came time for me to go to college,” he told Larry Whiteside in a 1982 interview, “I had to make a decision as to which position would get me the best shot of playing professional ball. I finally chose catching because a lot of young guys don’t stick with it because of the difficulty of the position. … I did pretty well as a catcher even though I didn’t like it.”4

Marc made the Florida varsity team as a freshman in 1977, but played in only nine games. He was the starting catcher in 1978, hitting .207 in 145 at-bats in 45 games. He missed half the season in 1979 with injuries, hitting .244 in 25 games. Sullivan’s batting statistics while playing two summers in the Cape Cod Baseball League were not impressive, either. He hit .270 for Orleans in 1977, with two home runs in 89 at-bats, and .245 for Chatham in 1978, with four home runs in 110 at-bats. (Most colleges and the Cape Cod League used aluminum bats, which tended to inflate hitting statistics compared with wood bats used in professional baseball.) Nonetheless, professional scouts liked Sullivan’s 6-foot-4 size, strong arm, and power-hitting potential. His playing weight is listed by baseball-reference.com as 205 pounds.

Marc decided to test the waters by declaring for the amateur draft after his junior season in 1979. “Dad and I talked about it a lot before I was drafted,” he later told Peter Gammons. “We went over everything: that I would stay in school if I weren’t drafted in the first three rounds. … We discussed the possibilities of being drafted by Boston. I knew there would be bad or negative aspects, but no matter where I went or whom I played for, I’d always hear stuff about my dad. If I couldn’t take that, then how could I take the hard part of the game?”5

Predictably, many were quick to charge that the Red Sox drafted Sullivan only because he was the general manager’s son. Haywood tried to deflect the criticisms. “Actually, I had nothing to do with the drafting, evaluating or selecting. That was done by [farm director] Eddie Kenney and [scouting director] Eddie Kasko. But I’ll still be the one who gets knocked for it.”6

Kenney defended the choice: “He’s a kid who looks like he can throw and hit. First-class catchers are hard to find.”7 Marc was perhaps the most realistic. “I realize there are plusses [sic and minuses,” he said. “No one in his right mind would believe they’d waste a high draft pick on the father-son thing. But it’s something I’ll have to get used to and play my way out of.”8

The Red Sox’ choice was somewhat vindicated in August when Marc was selected to The Sporting News All-American team. This team was selected by professional scouting directors, whereas the “official” All-American team was selected by the American Baseball Coaches Association. Cal State Fullerton’s Tim Wallach was the only player to appear on both teams. What team was the better predictor of professional success? It wasn’t close — seven of 11 members of The Sporting News team played five or more years in the major leagues, only two from the coaches’ team. Lou Pavlovich, editor of Collegiate Baseball magazine, said the professionals overlooked the fact that Sullivan had missed half the season. He “still was considered one of the fine catchers in college baseball. The scouts selected him on his known ability.”9

Sullivan recovered from his injuries in time to play 31 games in 1979 with Winter Haven in the Class-A Florida State League, where he hit only .207. But he impressed players and coaches with his defensive skills in his first spring training in 1980. Peter Gammons wrote that “Marc Sullivan will probably only be in [Double-A] Bristol, but ask any of the minor league pitchers, and they’ll tell you he is far away the best defensive catcher — receiving and throwing the ball.”10

Sullivan returned to Winter Haven in 1980 and struggled with a .225 batting average, but he made significant improvement at Winston-Salem in the Class-A Carolina League in 1981. He hit a so-so .268, but showed power with 21 doubles, 14 home runs, and an .807 OPS. Sullivan was also the league’s All-Star catcher, and was being compared to 6-foot-3 Carlton Fisk. “Marc’s going to hear it increasingly because he reminds me more of Carlton Fisk every day,” said Winston-Salem manager Buddy Hunter, who’d been Fisk’s teammate three years in the minor leagues.11 At least the focus was now on Sullivan the player, not on Sullivan the general manager’s son. At the beginning of the season he had refused interviews about anything other than the Winston-Salem Red Sox. “What I don’t like is when people want me to constantly comment on my father and the Red Sox. Who am I to do that? I’m a catcher in A ball.”12

Sullivan moved up to Bristol in the Double-A Eastern League in 1982, but went backward at the plate, hitting .203 with one home run. Nevertheless, Boston called him up on September 18 after Rich Gedman had broken his collarbone and manager Ralph Houk wanted a defensive catcher to help out. Sullivan made his first major-league appearance on October 1 at Yankee Stadium, replacing Gary Allenson in the seventh inning of a 12-inning 3-2 victory. He hit an infield single in his first at-bat against Yankees ace Ron Guidry, threw out a would-be basestealer, and drew a compliment from Houk, who said, “I’m not sure I’ve ever seen an arm like this. Maybe Lance Parrish, but Sullivan’s release is quicker.”13

Sullivan’s chances to make the major-league roster in 1983 were dashed when the Red Sox obtained veteran catcher Jeff Newman from Oakland in the offseason. Gedman and Gary Allenson had been splitting catching duties since Carlton Fisk had been lost to free agency after the 1980 season. Manager Houk basically carried only two catchers in 1981 and 1982, but decided to carry Newman as a third catcher in 1983. Sullivan was sent to Double-A New Britain (successor to Bristol), where he caught 43 games and also played 30 at first base. He got off to a great start and led the league in hitting after 30 games, but slumped to .229. His power numbers were good, though, with 15 doubles, 7 home runs, and a .772 OPS. He was moved to Triple-A Pawtucket at midseason, and was hitting only .186 in 27 games on August 15 when a foul tip fractured a fibula and sidelined him for the rest of the year.

Houk went with three catchers again in 1984, although Gedman became the undisputed number one — Allenson started only 27 games while Newman started 18. Sullivan spent the season at Pawtucket, where he hit .204, with 14 doubles, 1 triple, and 15 home runs in 383 at-bats. He played in two games at Boston as a September call-up.

Veteran manager John McNamara replaced the retiring Ralph Houk for the 1985 season. Gary Allenson had been granted free agency in November 1984 and it appeared that Sullivan had a good shot at making the squad as the number-three catcher. Newman, the presumed number two, was released on April 4, and McNamara decided to start the season with three catchers — Gedman, Sullivan, and Dave Sax, signed as a free agent from the Dodgers organization where he had hit a cumulative .307 in the last three years at Triple-A Albuquerque.

Boston’s beat writers finally seemed to give credit to Sullivan. The Globe’s Larry Whiteside wrote that he “made the squad on merit, not because he is the boss’ son.”14 The Boston Herald’s Joe Giuliotti wrote in The Sporting News that Sullivan “knows there have been, and probably always will be, those who whisper behind his back that he is in the big leagues because his father owns the club. But baseball people know that isn’t true.”15 Sullivan felt he earned the spot by hitting .280 in the exhibition season and playing well defensively.

By the end of April, McNamara decided to carry only two catchers and sent Sax to Pawtucket. Sullivan hit his first home run in the majors on May 15, a solo shot off Seattle’s Mark Langston. He made two appearances on the 15-day disabled list — on June 2 for a muscle tear in his left rib area, and on July 3 for a slightly fractured left wrist. Dave Sax was called back from Pawtucket in June and shared number-two catching duties with Sullivan for the rest of the season. Sullivan was hitting .240 before his first stint on the DL, but finished the season at .174. He started 23 games as a catcher, and played in a total of 32 games.

Despite his anemic hitting, Sullivan appeared to have the number-two catcher spot sewed up for 1986. Gedman had an All-Star year in 1985, hitting .295, compiling an .846 OPS, and starting 129 games. As a defensive specialist, Sullivan would be required only to spell Gedman once a week or so.

Sullivan had always taken advice on hitting from mentors inside and outside the organization, from Carl Yastrzemski, Ted Williams, Johnny Pesky, Sam Mele, anyone. The Boston Globe’s Leigh Montville described some intense sessions with Yaz in spring training. “The search continues. Head down. Head up. Closed stance. Swing. Swing again. … Hitting a thrown baseball is the toughest act to perform in American sport. Watch Wade Boggs hit the ball here and there and everywhere and you sometimes forget that fact. Watch Marc Sullivan and you remember.”16

The Red Sox were 32—15 and in first place at the end of May, 2½ games ahead of the Yankees, and pennant fever began to strike New England. Sullivan started strong, too, and was hitting .306 (11-for-36) in 12 games through May 30, but went 12-for-83 the rest of the season to finish at .193. Fans got on him as his offensive futility grew. He was loudly booed when he struck out twice with runners on base in a game on August 31. Then he struck out his first three times at bat in his next game on September 3, bringing his average down to a season-low .168. Sullivan was placed on the 24-man postseason roster, but did not play in Boston’s seven-game Championship Series victory over California or in their seven-game World Series loss to the New York Mets.

The Red Sox missed the deadline to sign free agent Rich Gedman on January 8, 1987, making him eligible to sign with other clubs and preventing Boston from re-signing him until May 1. Gedman’s absence meant that Sullivan was the starting catcher when spring training started. He knew he was on the spot. “It’s a good situation,” Sullivan told Boston Globe writer Larry Whiteside. “I’ve got a chance to be No. 1 until May 1. … Don’t get me wrong. I didn’t go out and do handstands on Jan. 8. But I knew the situation with Geddy and I know what it means to me. I’ve even spoken with him about it.”17

Many still doubted Sullivan’s credentials. “Life isn’t easy for the boss’ kid when the boss’ kid works in the boss’ shop,” wrote the Globe’s Dan Shaughnessy. “Everyone assumes that you’re only there because blood is thicker than pine tar. The paying public chuckles smugly and some of your coworkers think you’re a snitch. … Sullivan has it tougher than most bosses’ kids. He carries the weight of Rich Gedman’s contract dispute, Roger Clemens’ walkout and his own anemic .200 career batting average. He knows a large percentage of the public believes the Sox failed to sign Gedman to Make Room For Sonny.”18 Sullivan was able to shake off some of the critics. “They keep calling me ‘May 1,’ ” he said with a smile. “Then they ask me what I am going to be doing May 2 when (Rich) Gedman comes back.”19

Johnny Marzano, an All-American with Temple in 1984, and the leading hitter on the US Olympic team in Los Angeles, was thought to be ready to challenge Sullivan for the starting position, but he hit only .194 in spring training and did not field very well. Sullivan solidified his position by hitting .350 in spring training. Manager McNamara went north with three catchers, Sullivan, Dave Sax, and Danny Sheaffer. The 25-year-old Sheaffer had been in the Boston organization since 1981 and hit .340 at Triple-A Pawtucket in 1986.

Sullivan got hits in his first three games to start the season, including a home run on the first pitch he saw in the home opener against Toronto. But he got only four hits in his next 11 games, and at the end of April, after starting 14 of the team’s first 22 games, he was hitting .163. Sheaffer caught the other eight games, but his .179 was not much of an improvement.

Meanwhile, Gedman signed a two-year deal for a reported $883,000 per year, and played his first game on May 2, pinch-hitting for Sheaffer at Anaheim. Gedman’s layoff appeared to have taken a toll — he never did display the batting stroke that earned him All-Star honors the previous two years. Gedman went on the disabled list in early July for a pulled groin muscle, and then on July 27 severely injured thumb ligaments on his left hand and was done for the season. He hit only .205, with one home run in 52 games.

Boston called Marzano up from Pawtucket to replace Gedman. At the time Sullivan was hitting only .171, while Sheaffer was at an anemic .107. They were having defensive problems, as well — Gedman and Sullivan had been charged with eight passed balls each. The team was 47—54 and going nowhere. It seemed like a good time to see what Marzano could do. “It makes no sense to let (Marzano) sit,” manager McNamara told the Herald’s Joe Giuliotti. “He’s here. Let’s find out about him.”20 Marzano caught 48 of the team’s remaining games while Sullivan played in only 11 games the rest of the season.

Sullivan was a frequent target of boo-birds when he did play. It was especially vocal at a game on June 23, when he had a passed ball and struck out twice before being replaced by a pinch-hitter. The stoic catcher, who usually suffered his critics in silence, uncharacteristically lashed out at fans. “That’s nothing new here,” Sullivan told Globe reporter Kevin Paul Dupont. “That showed the kind of fans we’ve got here. They don’t give a damn. That’s all I’ve got to say. I try the best I can.” Sullivan pointed out that Boston fans had once demeaned the Minnesota Twins’ Jim Eisenreich when he was suffering with Tourette’s syndrome.21

On July 26 the Globe’s Jack Craig unloaded on Sullivan for striking out with the bases loaded in the July 21, 3—0 win over the Angels at Fenway Park. “The longer Sullivan plays, the more it appears he is on the team because his father, team co-owner Haywood Sullivan, wants Marc and his young family to enjoy the good life in the majors rather than the bad life in the minors. As [sports radio talk show host] Eddie Andelman repeatedly says on WHDH, he would do the same thing for his kid.”22

At the close of the season Sullivan revealed he planned to try pitching in the Florida Instructional League. He told Joe Giuliotti that he actually began the process a month earlier when he started going to Fenway early and throwing to pitching coach Bill Fischer. “I’d throw for 10 to 14 minutes a day and once threw three days in a row so Fischer could see how my arm bounced back, and it responded well.”23 Sullivan had pitched a little in high school, and last pitched a few games in relief in the Cape Cod League in 1977 and 1978. But his plans were derailed when he injured his elbow before he had a chance to pitch in his first game.

Meanwhile, Red Sox general manager Lou Gorman was planning to trade Sullivan. He said he first talked to Haywood Sullivan about it near the end of the season. Haywood agreed. “His dad didn’t interfere in the slightest,” said Gorman. “But, like I said, it was delicate, trading a young man who happens to be the son of my boss. … What was tough for Marc was that he was under a lot of tremendous pressure here. The fans would get on him for his hitting or the fans would take out on him their frustrations with the team and Marc took a lot of guff for being the owner’s son. But the thing is that Marc never opened his mouth about it, never complained, never said it was unfair.”24

Sullivan was traded to the Houston Astros on December 14, 1987, for minor-league infielder Randy Randle. He seemed pleased. “The time is right for something like this to happen. Now maybe the focus can be on Marc Sullivan, the player, and not the owner’s kid.”25

Sullivan never made it back to the major leagues. A sore elbow limited his playing time, and Houston released him at the end of spring training. The Philadelphia Phillies signed him to a Triple-A contract to play for their Maine affiliate in the International League. Phillies catcher Darren Daulton broke his hand when he punched a locker-room wall after a game on August 27. Sullivan might have been called up to replace Daulton, but he had an injured left hand. The White Sox signed Sullivan to a Triple-A contract in 1989, and he played 84 games for Vancouver in the Pacific Coast League.

February 1990 found Sullivan working out during the major-league lockout at the Red Sox training camp in Winter Haven, waiting to be offered a minor-league contract. (He could legally use the locked-out facility because he was a nonroster player.) “The last two years, I’ve been a player-coach, even though I haven’t had the title,” he told the Boston Globe’s Nick Cafardo. “I’ve been working with young pitchers and young players and I’ve really enjoyed it. I know now that I’d like to coach and manage in the minor leagues and someday make it to the majors.”26

Sullivan eventually signed as a catching instructor in the Cleveland organization. He caught 12 games late in the season to fill a vacancy with Colorado Springs of the Pacific Coast League. That would be the end of his playing days. He was hired as an American League advance scout by the Texas Rangers in 1991. He was rumored to be a candidate for major-league coaching positions in the next several years, but none of them panned out. The Rangers dropped him in November 1994.

Sullivan has been involved in Fort Myers and southwest Florida real-estate development in his post-baseball career. As of 2015 he was president of Sullivan-Florida Group Inc., owner-operator of the Legacy Harbour Marina, Legacy Harbour Hotel & Suites, and Caloosahatchee Development & Realty Inc. He and his wife, Angela, have four children, Loreal (born in 1986), Brandon, Sierra, and Krystle.

Time seems to have removed any pain left over from Sullivan’s difficult years in Boston. He has been involved in Red Sox fantasy camps for almost 20 years, as a member of pro-advisory staffs, as a camp director, and for a few years as the co-owner of New England Sports Franchises, the former owner of the franchise.

He returned to Fenway Park for a June 27, 2006, pregame ceremony at a game with — of course — the New York Mets, honoring the Red Sox’ 1986 team. It was a heartwarming event … for fans as well as the old players. Bill Buckner, the ’86 Series goat, said he couldn’t attend because of a personal conflict, but his image on the video board was greeted with cheers. “That was really nice,” [1986 second baseman] Marty Barrett said of Buckner’s reception. “I wish he were here to see that. It would have been fun. The fans here know. They got a win in 2004, and all of that was released, ’46, ’67, ’75, ’86, all of those guys feel like there’s a weight lifted off their shoulders.”

“You know what’s interesting, and I really never thought about it,” Barrett continued, “somebody told me the other day all these teams wanted to win it for the fans. But I heard the fans couldn’t wait for a team to win it to help all of us who couldn’t get it done. I thought that was pretty neat.”27

Marc Sullivan had to feel the love as he jogged to his old position behind the plate.

Sources

In addition to the sources indicated in the notes, the author also consulted:

Baseball-reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and the University of Florida Athletics, gatorzone.com. He also accessed the Marc Sullivan player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, the 1975 Canton High School Yearbook, via archive.org, and corresponded by e-mail with

Bob Sherman, Chatham (Cape Cod Baseball League) vice president, on July 25, 2015, and with Judy Scarafile, Cape Cod Baseball League president, on July 28, 2015.

Notes

1 Dan Shaughnessy, “2 Pitchers Demoted; More Cuts Today,” Boston Globe, March 28, 1986.

2 Dan Shaughnessy, “One Giant Leap for a Franchise,” Boston Globe, April 27, 1986.

3 “Another Sullivan for Florida,” St. Petersburg Times, July 13, 1976: 3C.

4 Larry Whiteside, “In Dad’s Footsteps; Marc Sullivan Finds Being the Boss’ Son is Both Burden, Blessing,” Boston Globe, February 28, 1982.

5 Peter Gammons, “Marc Sullivan Showing He’s More Than Haywood’s Son,” Boston Globe, July 2, 1981.

6 Larry Whiteside, “Red Sox’ No. 1 Draft Choice is the son of G.M. Sullivan,” The Sporting News, June 23, 1979: 6.

9 Lou Pavlovich, “Slugger Wallach Leads Collegiate All-Star Choices,” The Sporting News, August 11, 1979: 9.

10 Peter Gammons, “Ainge Won’t Pass Up Deal With Blue Jays,” Boston Globe, March 22, 1980.

11 Gammons, “Mark Sullivan Showing …,” Boston Globe, July 2, 1981.

13 Peter Gammons, “Denman Stymies NY, 5-0,” Boston Globe, October 3, 1982.

14 Larry Whiteside, “Trujillo Up, Brown Down; Sox Drop Newman, Retain Sax,” Boston Globe, April 5, 1985.

15 Joe Giuliotti, “Work, Not Nepotism, Is Sullivan’s Ticket,” The Sporting News, April 29, 1985: 16.

16 Leigh Montville, “For Marc Sullivan, It’s Strictly Hit or Miss,” Boston Globe, March 24, 1986.

17 Larry Whiteside, “Sullivan Catches a Break,” Boston Globe, February 22, 1987.

18 Dan Shaughnessy, “Sullivan a Rising Son in Rout,” Boston Globe, March 8, 1987.

19 Larry Whiteside, “Pagliarulo Is Producing; New Papa Is Playing With Pride,” Boston Globe, March 17, 1987.

20 Joe Giuliotti, “Something to Remember,” The Sporting News, August 17, 1987: 23.

21 Kevin Paul Dupont, “No Big Move; Benzinger Sticking With His Old Home,” Boston Globe, June 25, 1987.

22 Jack Craig, “Strategic Silence Coming From Sox’ Booth?” Boston Globe, July 26, 1987: 57.

23 Joe Giuliotti, “Sullivan Makes a Pitch,” The Sporting News, October 12, 1987: 24.

24 Michael Madden, “A Relatively Good Trade,” Boston Globe, December 15, 1987.

25 “Notebook; N.L. West,” The Sporting News, January 4, 1988: 58.

26 Nick Cafardo,”Staying in the Game: Sullivan Eyes Minors, Then the Front Office,” Boston Globe, February 20, 1990.

27 Chris Snow, “’86ers Really Appreciate a Class Gesture,” Boston Globe, June 28, 2006.

Full Name

Marc Cooper Sullivan

Born

July 25, 1958 at Quincy, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.