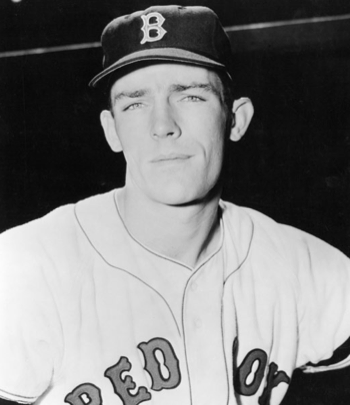

Haywood Sullivan

Haywood Cooper Sullivan was many things during his life: passing record holder at Dothan High School (Alabama), college All-SEC quarterback and baseball standout (Florida), bonus baby, American League catcher, manager, general manager, and major-league ballclub owner, and to top it off, a self-made millionaire. Sullivan was born in Donalsonville, Georgia on December 15, 1930, and raised in Dothan, in southeastern Alabama, where he played both football and baseball in high school and was considered a blue-chip quarterback.

Haywood Cooper Sullivan was many things during his life: passing record holder at Dothan High School (Alabama), college All-SEC quarterback and baseball standout (Florida), bonus baby, American League catcher, manager, general manager, and major-league ballclub owner, and to top it off, a self-made millionaire. Sullivan was born in Donalsonville, Georgia on December 15, 1930, and raised in Dothan, in southeastern Alabama, where he played both football and baseball in high school and was considered a blue-chip quarterback.

Upon leaving high school, Sullivan was heavily recruited to play football by both Auburn and Alabama, but chose Florida because he considered their offense to be more wide open and passing-oriented.1 Sullivan, who grew up in a working-class family, born to Ralph and Ruby (Lee) Sullivan, had many things to consider when making his decision on where to play. Ralph worked as a truck driver for Newton Grocery Company in 1939 and as a shipping clerk for Blumberg’s Department Store in 1951.2 Location of the school was a major factor as Sullivan’s family did not own a car. Sullivan had a former high school teammate, William A. “Bubba” McGowan, who was already attending Florida and was a holdover from the 1949 season. The McGowans traveled to Gainesville to see their son play on a regular basis and could give the Sullivans a ride. It may not have been the deciding factor but having a way for his family to see him play definitely weighed heavily in Haywood’s decision.

McGowan often talked of Sullivan’s power arm and swears that he once saw him throw a baseball from one goal line to the other on a single bounce. McGowan also proclaimed that Sullivan had such a soft touch that his passes were easily catchable by his receivers. Sullivan’s “catchable ball” was one of the main reasons he was named All-SEC quarterback with some thinking he was good enough to have been All-American. Haywood was also a standout on the baseball field and was referred to as a man among boys. Buddy Martin, writing in The Boys from Old Florida: Inside Gator Nation stated in a later time, NFL scouts would have been throwing money at Sullivan – but pro football didn’t pay as much as baseball in those days.

Sullivan received a great deal of attention from major-league scouts. In the end, the Boston Red Sox offered Sullivan a $75,000 bonus and Bob Woodruff, Florida’s football head coach sought the help of future baseball Hall of Famer Bill Terry for advice. Terry asked Sullivan, “Do you mean to tell me you get this money even if you don’t make it to the big leagues?” Sullivan said that he did and Terry replied, “Then boy, what are you waiting for?” Hardly the response Woodruff was expecting from the guy he brought in to keep his quarterback on the team. Sullivan signed with the Red Sox in June 1952, thus ending his football career.

Sullivan began his minor league career with the Albany (New York) Senators on June 15, hitting an RBI double in his first at-bat.3 For the year, Sullivan played in 61 games batting .295 (54-for-183) with six home runs. In 1953 he was thought to have a good shot at the third-string catcher job with the big-league ballclub. Sullivan’s hot start with the Red Sox in spring training came to an end on March 22 when he was forced to leave the team before reporting to the Army draft board in Alabama on April 9, 1953.4

While in the service, Sullivan played quarterback for the Fort Jackson (South Carolina) football team5 and also played baseball. He missed two baseball seasons to military service, but returned in 1955 with the Double-A Louisville Colonels as one of baseball’s best catching prospects. In 128 games with Louisville, the 24-year-old Sullivan batted .258 while slugging .389 – numbers good enough for the American Association all-star team.

Haywood made his major-league debut on September 20, 1955 at Fenway Park. He batted eighth and was the starting catcher with battery mate Ike Delock. Sullivan was hitless in two at-bats before he was lifted for pinch-hitter Ted Williams. Sullivan appeared in one other game that season, a September 25 tilt against the Yankees in Boston. Haywood Sullivan caught Frank Sullivan (no relation) and went 0-for-4 at the plate. In 1956, Sullivan was named an all-star again with the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League, then the Red Sox top affiliate. He threw out 28 runners and was able to raise his average to .296 and his slugging percentage to .433 thanks to 11 home runs and 32 doubles

Coming into the 1957 season, Sullivan was thought to have a shot to stick with Boston. His 6-feet-3, 220-pound frame and that he was a right-handed, long-ball hitter were said to be a perfect fit for Fenway Park.6 Boston brought in Sheriff Warren Robinson, manager of Boston’s Oklahoma City farm team, to tutor Haywood on the finer points of catching.7 He made the Opening Day roster, and played two early season games, finishing 0-for-1 as a hitter. When rosters had to be reduced on May 15, Sullivan was optioned to the Miami Marlins.

He reported to Miami on May 19 after making the 1,600 mile trip by car; he hit a 400-foot home run in his debut.8 After just 60 at-bats over 17 games he was transferred back to San Francisco in late June to share catching duties with Eddie Sadowski.9

For the season he hit .274 in 90 games overall. At age 26, Sullivan was no longer the prospect he had once been. In November, rumors surfaced the club was considering moving him to first base, but Boston needed a hard-hitting catcher more.10

In 1958 Sullivan was in the mix once again, hoping to make the team. Sammy White had been Boston’s catcher for six years, but Sullivan had an opportunity because of his badly needed right-handed power.11 Unfortunately, Sullivan suffered a badly-broken right index finger during a preseason game against the Washington Senators and was sidelined for several weeks.12

Shortly after, he developed back trouble and a Sarasota doctor recommended the Red Sox send him to a neurosurgeon. Sullivan was flown to Boston and it was soon determined he had a slipped disk and needed an operation. Surgery was performed by Dr. John Poppen, who determined Sullivan had a ruptured disk and wouldn’t be able to work out for at least two months.13 In fact, he missed the entire 1958 season. He was still voted a full share of the players’ pot for the team’s third place showing that season.14

In all, Boston had invested nearly $1 million on Sullivan and other “bonus baby” players in the early 1950s and none of them had become a star player. Some had been traded and some, like Haywood, were by 1959 facing what might be their last chance with the team.15 He’d always hit well in the minors, and it was said there was no player in Red Sox history who had more people rooting for him than Haywood Sullivan coming into the 1959 season. He arrived at spring training fully recovered thanks to a regimen of offseason swimming.16 Sullivan began the season as the Red Sox third string catcher, but rarely played–just four game and two hitless at-bats through June 12. He was then demoted to the Triple-A Minneapolis Millers. In 57 games with the Millers, Sullivan batted just .235 with eight doubles. Sullivan did help the Millers win their second consecutive American Association championship.

With Sammy White holding out, Sullivan began the 1960 season sharing the catching with rookie Ed Sadowski. In April Sullivan was voted the Hardest Worker in Camp, Surprise of Training Season, Most Improved Player, and for the third consecutive season, the Most Likely to Improve by The Sporting News.17 After six years and 15 at-bats Sullivan recorded his first major league hit on April 19 off the Yankees’ Jim Coates. His first homer came on May 17 of Chicago’s Bob Shaw. Overall, he posted a .161 batting average in 52 games with three home runs and 10 RBIs in 124 at-bats, hardly what people expected out of a would-be hard-hitting receiver. In June, the Red Sox acquired catcher Russ Nixon from the Indians, who promptly took over as the starting catcher.

On December 14, 1960 Haywood’s tenure with the Boston Red Sox came to an end when he was selected by the new Washington Senators in the 1960 expansion draft. The Senators sent Sullivan to the Kansas City Athletics two weeks later for Marty Kutyna.18

In 1961 Sullivan spent a majority of his time behind the plate but also played first base and both corner outfield positions while batting .242 with six home runs and 40 RBIs, spread over a career high 117 games. Sullivan played two more seasons with the Athletics but he never became the offensive catcher people thought he would. He hit .248 in 95 games in 1962, then .212 in 40 games the next year. In July 1963 he joined the Triple-A Portland Beavers as a player/coach, and Sullivan decided to put an end to his professional baseball-playing career to pursue a managerial post within the Kansas City farm system.19

In 1964 he skippered the Birmingham Barons of the Southern League. The next year, he was placed in Triple A, to manage the 1965 Vancouver Mounties. His season started off like his previous two until a rainy Saturday in May. He’d been out house-hunting in Vancouver, but found a message waiting for him when he returned to his hotel: call Kansas City. Forty-five minutes later, Sullivan was the Athletics’ new manager and en route to Kansas City. At age 34, Sullivan was the youngest manager in the major leagues at the time. Although Sullivan was young and inexperienced, the organization believed he demonstrated exceptional qualities of leadership and the ability to get the most out of his players, which they considered to be very important.20 The club began the season 5-21 for Mel McGaha, then Sullivan managed the A’s to a 54-82 record. General Manager Hank Peters was a big fan of Haywood and believed that Sullivan had done an outstanding job as manager.

Under owner Charles Finley, no manager was ever safe.21 By late August speculation began to mount that both Sullivan and Peters were on their way out. On the night the World Series ended, Finley offered the GM position to Al Campanis of the Dodgers.22 Peters was out as GM and Sullivan voluntarily resigned shortly thereafter, despite assurances by Finley the managing job was his for the ’66 season. Instead, he took the position of Director of Player Personnel with the Red Sox.23 Returning to the team who had first signed him, he would work under newly promoted general manager Dick O’Connell.24

In an interview, Sullivan stressed he left Kansas City on good terms with Charlie Finley and was very grateful for the opportunity he had given him to manage. If it weren’t for Finley granting O’Connell permission to speak to him, Sullivan would have remained the Kansas City manager for another season. He’d been a favorite of the Boston writers and he was warmly greeted when his hiring was announced at the minor league meetings. Both O’Connell and team owner Tom Yawkey were fully behind the team’s new direction, so much so that Yawkey attended the winter meetings for the first time in seven years.25

The Red Sox were coming off a 62-100 season, their worst record since 1932. During the first six weeks on the job, all Sullivan did was read: rules, scouting reports on players on the Red Sox or other clubs. One thing Sullivan found challenging at first was evaluating players and learning how the scouts within the Red Sox organization rated players. Having a strong working knowledge of the players on the Kansas City Athletics, Sullivan took reports on A’s players and was able to gain valuable insight into how some of the Boston scouts evaluated players.26

Although Sullivan had originally acted more as a partner to O’Connell, who had never played or managed or run a ballclub before, O’Connell gradually took over more and more control of the club. After the Red Sox surprise 1967 pennant, O’Connell was named Executive of the Year by The Sporting News, and his role as the team’s architect and sole trader was well understood. This continued until the early 1970s when Sullivan had become the director of amateur scouting for the club. Despite Sullivan’s decreased role with the organization, he maintained a very close relationship with Tom Yawkey and his wife Jean. Sullivan had worked under O’Connell and Yawkey for 12 seasons and had become Yawkey’s liaison man and confidant, and a very close friend. On July 9, 1976, after 44 years of ownership, Tom Yawkey died of leukemia and the Boston Red Sox were put up for sale a year later. The Red Sox were considered one of the crown jewels of the American League at the time attracted a number of bids. A group headed by Sullivan and former Red Sox trainer Buddy LeRoux was awarded the franchise, though theirs was not the highest offer. Other bids, including a higher one by A-T-O, the owner of Rawlings Sporting Goods Co., were rejected by the trustees administering the the Yawkey Trust, which included Jean Yawkey. One of the stipulations of the sale of the club was that it need not be sold to the highest bidder. The reality was that Mrs. Yawkey was not being forced to sell the team by the courts or any other entity, and was free to make her own deal.27

Although the Sullivan-LeRoux bid had been accepted by Jean Yawkey, the deal still needed to be approved by the league. Concerns were raised by several American League officials because the Sullivan-LeRoux offer was so reliant on borrowed money.28 On October 24, in a event engineered by Mrs. Yawkey herself, Dick O’Connell and two other team officials were fired and Sullivan was named general manager.29

The sale of the club dragged on. A lawsuit was filed by rejected bidder A-T-O and an advocate group led by Ralph Nader suggested Boston’s fans would be short-changed by the sale.30 In December of 1977, the sale of the Red Sox to Sullivan and LeRoux was rejected by the American League. League officials advised the Sullivan-LeRoux group to find a managing partner who had money, the kind the league could call if support was needed for the club in hard times.31

In March 1978, Jean Yawkey became a full general partner when she donated Fenway Park valued at $5.5 million, plus $1 million in cash to the Sullivan-LeRoux group bringing the total bid to $20.5 million. The suit filed by A-T-O was dismissed and the new Sullivan-LeRoux prospectus was mailed to the American League owners.32 The deal was approved in May of 1978 and the trio officially took over full control of the club.

The 1978 season was the first for Sullivan as GM and it was a memorable one for fans of the Boston Red Sox. On July 8, Boston held a 10-game lead in the American League East Division but was overtaken by New York in mid-September. The Red Sox managed to tie the Yankees on the last day of the season thanks to an eight-game win streak and force a single-game playoff for the pennant, won by the Yankees.

In 1979, the Boston Red Sox selected Marc Sullivan, Haywood’s son, with the 52nd pick in the draft. The Red Sox claimed they had Marc rated as the number two catcher in the draft. Haywood Sullivan stated numerous times that he “had nothing to do with the drafting, evaluating or selecting. That was done by Eddie Kasko. But I’ll be the one who gets knocked for it.”33 Marc Sullivan managed to reach the major leagues, playing parts of five seasons with the Red Sox, including three as the second-string catcher. He hit just .186 in 137 games, and he and his father were ridiculed as long as he remained in the organization.

Haywood Sullivan remained the general manager with Boston until February of 1984. During his six seasons as GM, the Red Sox posted a 499-416 record, a .545 winning percentage. In 1977, Sullivan said, “I don’t think you can trade a Fisk, a Jimmy Rice, a Fred Lynn, a Carl Yastrzemski, or a Rick Burleson. When you trade key men like that, you are just defeating your own purpose.”34 Before the 1981 season Sullivan, however, did just that, trading Rick Burleson, Butch Hobson, and Fred Lynn and most famously, letting Carlton Fisk become a free agent after he failed to offer Fisk player a contract before the deadline set forth by Major League Baseball. Other than Fisk, the players were traded because the team did not want to pay them according to the much higher salary levels that players were beginning to attain in this period. He and Buddy LeRoux became unpopular with Boston fans and with the team. Boston had lost three of their most popular players in one offseason and outside on Yawkey Way, vendors were selling bumper stickers that read HAYWOOD AND BUDDY ARE KILLING THE SOX.

Baseball was changing. Lacking the money Yawkey often poured into the club, the team suffered. “We finished in fourth place with them; we can finish in fourth place without them,” said Sullivan, and that was the new outlook of the ownership group. The organization was having a hard time adjusting to free agency and the new. Sullivan expressed a yearning for times of the past when players and agents weren’t involved in contract negotiations and said, “I like the days when everyone had a good time around baseball.”35

The relationship between the trio of owners began to deteriorate as the seasons went on. On June 6, 1983, on a night meant to honor former star Tony Conigliaro, struck down by a stroke, Buddy LeRoux, acting on behalf of limited partners Al Curran and Rogers Badgett, declared war. Before a scheduled general partners’ meeting, LeRoux informed Sullivan and John Harrington, Jean Yawkey’s representative, that he was seizing control. LeRoux claimed that he held sway over 16 of the 30 limited partnership shares and had drafted an amendment to the partnership agreement making himself “managing general partner.”36

LeRoux then announced that he was firing Sullivan, replacing him with former GM Dick O’Connell. The event was a huge embarrassment for the club and Peter Gammons wrote in the June 20, 1983 issue of The Sporting News, “The fascination and romance that of the current Red Sox era grew from the ’67 team ended at 4:42 pm when LeRoux walked in and announced that he was in charge and had fired Sullivan. As singer Don McLean might have put it, this was the night the music died.”

The two sides met the next day in court with Sullivan and Yawkey declaring that LeRoux was trying to usurp all power, that the team was already being well managed–“They were in first place yesterday”–and that the LeRoux amendments were void and of no effect. The LeRoux side stated they hadn’t had enough time to prepare a response to the claim and court was adjourned until the next day. The following morning, Sullivan and Yawkey stated the original partnership agreement clearly prohibited the limited partners from interfering in the general partners’ management of the club and although LeRoux may have had a majority of shares, he didn’t have a majority of general partners. At 3:55 the judge ruled in favor of Sullivan and Yawkey. “Whenever you go to court, there are no victories,” said Sullivan at his post-hearing press conference. There was also no victory for the Red Sox that night on the field although Bob Stanley was quoted as saying, “We’ll win tonight. We just didn’t want to win for Buddy.”37

Following the 1983 season, Sullivan voluntarily gave up his seat as general manager to the newly hired Lou Gorman to become the team’s chief executive and chief operating officer. Buddy LeRoux remained with the team until 1986 and his general partnership share would eventually be bought by Mrs. Yawkey. After LeRoux’s departure, Sullivan and Jean Yawkey began to grow distant. By the late 1980s Sullivan was consistently outvoted 2-1 by Yawkey’s two general partnership votes. Mrs. Yawkey lived until 1992 and upon her death, her representative John Harrington bought out Sullivan. Sullivan had invested $100,000 when he became a general partner in 1978, and had also received a $1 million loan from Mrs. Yawkey to help finance his share of the ownership. In November 1993 Sullivan sold his minority interest in the team to John Harrington and the Jean R. Yawkey Trust for an estimated $36 million to $45 million.38

Sullivan became a real estate developer in Fort Myers and also ran a marina. He remained in Florida until his death on February 12, 2003. ”I came from nothing,” Sullivan told the Boston Globe in 1994. ”I was a player in an era when you didn’t ever go up to the front office. I moved along as a coach and a manager. But never in my wildest dreams did I feel I would be involved in ownership.”

Notes

1 Buddy Martin, The Boys from Old Florida: Inside Gator Nation (Champagne, IL: Sports Publishing, 2006), 32-33.

2 Thanks to Susan Veasey of the Houston Love Memorial Library for checking Dothan city directories.

3 The Sporting News, June 25, 1952, 33.

4 The Sporting News, April 1, 1953, 22.

5 The Sporting News, September 2, 1953, 38.

6 The Sporting News, February 27, 1957, 8.

7 The Sporting News, March 20, 1957, 5.

8 The Sporting News, May 29, 1957, 32.

9 The Sporting News, July 3, 1957, 38.

10 The Sporting News, November 6, 1957, 15.

11 The Sporting News, February 26, 1958, 19.

12 The Sporting News, April 9, 1958, 16.

13 The Sporting News, April 16, 1958, 8.

14 The Sporting News, October 22, 1958, 9.

15 The Sporting News, November 26, 1958, 30.

16 The Sporting News, March 4, 1959, 8.

17 The Sporting News, April 13, 1960, 14.

18 http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/s/sulliha02.shtml.

19 The Sporting News, July 27, 1963, 31.

20 The Sporting News, May 29, 1965, 15.

21 The Sporting News, August 14, 1965, 17.

22 The Sporting News, October 30, 1965, 31.

23 The Sporting News, December 11, 1965, 6.

24 The Sporting News, December 11, 1965, 15.

25 The Sporting News, December 11, 1965, 6.

26 The Sporting News, January 22, 1966, 13.

27 The Sporting News, October 15, 1977, 9.

28 Ibid.

29 The Sporting News, November 5, 1977, 20.

30 The Sporting News, November 19, 1977, 43.

31 The Sporting News, February 4, 1978, 45.

32 The Sporting News, March 18, 1978, 45.

33 The Sporting News, June 23, 1979, 6.

34 Sports Illustrated, May 11, 1981.

35 http://www.sonsofsamhorn.net/wiki/index.php/Haywood_Sullivan.

36 http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1120951/2/index.htm.

37 http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1120951/3/index.htm.

38 http://www.nytimes.com/2003/02/14/sports/haywood-sullivan-72-player-and-later-a-red-sox-owner.html?pagewanted=1.

Full Name

Haywood Cooper Sullivan

Born

December 15, 1930 at Donalsonville, GA (USA)

Died

February 12, 2003 at Fort Myers, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.