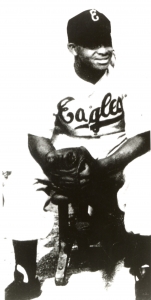

Benny Felder

Newark Eagles shortstop Benny Felder was born on December 9, 1926, in Tampa, Florida.1 Little is known of his family. In an interview with Brent Kelley, Felder said, “My family was brick masons.”2 Benjamin Franklin Felder was the ninth of 10 children born to Porter Henry Felder (1882-1944) and Minnie Lee (Fluker) Felder (1886-1979). The couple had seven sons and three daughters, and they seemed to favor naming the sons after public figures – among Benny’s brothers were Frederic Douglas Felder and Booker T. Felder.3

Newark Eagles shortstop Benny Felder was born on December 9, 1926, in Tampa, Florida.1 Little is known of his family. In an interview with Brent Kelley, Felder said, “My family was brick masons.”2 Benjamin Franklin Felder was the ninth of 10 children born to Porter Henry Felder (1882-1944) and Minnie Lee (Fluker) Felder (1886-1979). The couple had seven sons and three daughters, and they seemed to favor naming the sons after public figures – among Benny’s brothers were Frederic Douglas Felder and Booker T. Felder.3

Porter Felder worked as a roofing tie contractor in Argyle, Georgia, at the time of the 1920 Census, but by 1930 was listed as a brick mason in Tampa, as was his eldest son, Mitchel. Minnie worked as a servant for a private family. Porter Felder’s father, Dow Felder, had been a farm laborer. Porter was an Alabaman and Minnie a Georgian by birth.

Growing up in Tampa during the late 1930s, Felder played baseball, which was a popular sport among his African-American friends. He played for the Pepsi-Cola Giants, an independent Negro team. Felder recalled, “I really just got out on the field when I was around 13, 14 years old. I played with Pepsi-Cola about three or four years.”4 Higher-level Negro League teams trained in Florida and – just as was the case with his friends and fellow Giants John and Walter “Dirk” Gibbons, Raydell Lefty Bo Maddix, and Clifford “Quack” Brown – Felder’s skills were soon recognized. All five of these men made it to the top levels of the Negro Leagues.

On Easter Sunday and Monday, April 21 and 22, 1946, Felder’s Giants played exhibition games against the Negro National League’s Newark Eagles in Port Tampa. The Eagles had finished third in the six-team NNL the previous year with a squad led by backstop and future Hall of Famer Raleigh “Biz” Mackey. Future Brooklyn Dodgers ace Don Newcombe had been their top pitcher in 1945, having posted an 8-2 record.5

Felder related that he had two good games in the series against Eagles pitching stars Leon Day and Rufus Lewis, both of whom were returning from military service. Felder fielded well in the games and recorded multiple hits each day. Abe Manley, owner of the Eagles, took notice of his performance. After a dinner at the Felder home in Tampa, Manley persuaded a skeptical mother to let her son join the club. Felder explained, “You know how it is. You want to get away to see how things are. Abe told her to let me give a try ’cause I wanted to try it anyway, so she agreed.”6 Thus, the 19-year-old Felder – who batted and threw right-handed and was listed as 5-feet-9 and 170 pounds – entered the Negro Leagues in 1946 as an infielder with the Newark Eagles.

One of Felder’s biggest thrills in baseball involved an Eagles teammate, future Hall of Famer Leon Day.7 On Opening Day in 1946, after returning from a 2½-year stint in the Army, Day hurled a no-hitter against the Philadelphia Stars at Ruppert Stadium in Newark. Day faced 29 batters, with no baserunner reaching second base. One batter was walked and two reached first base as a result of Felder’s errors. One error was erased by an Eagles double play. “Felder was just a young kid. He could field pretty good but he wasn’t that sure and he might overrun anything,” Day recalled.8 One of the recorded errors may have been questionable. After fielding the ball cleanly, Felder took three or four bunny hops before making the toss to first. In so doing, he made a bad throw. The runner may have been out. The scorer also could have classified it a hit. It was officially recorded as an error, thereby saving Day’s notable no-hitter. The miscues could not erase Felder’s thrill in playing behind the great right-hander on this special day.

Though Felder began the season with the Eagles, he was released in early June to make way for Oscar Givens.9 Felder was back with Newark at the beginning of the 1947 season but then was traded to a team in North Carolina. According to Felder, “I went down there to spring training, but I didn’t stay. I didn’t like it.” He returned to Tampa, where he again played for the Pepsi-Cola team.”10

In 1948, thanks to his friend and former Pepsi-Cola Giants teammate Walter “Dirk” Gibbons, Felder joined the Indianapolis Clowns. The Clowns had become a barnstorming team, and Felder recalled how exhausting his stint with that franchise was, especially in regard to finding time to eat in order to maintain any stamina. He related:

We was getting $2.50 a day for meals. I learned how to eat pork and beans and sardines. A lot of times, like when we were playing with the Clowns, the Clowns played every day, sometimes two and three games a day, and you didn’t get a chance to stop to eat. You got to run in a grocery store and get a loaf of bread and lunch meat or stuff like that to eat.11

In spite of such conditions, Felder enjoyed himself, saying, “I didn’t make no money, but I got a lot of experience.”12

After spending the 1948 season with the Clowns, Felder was out of baseball in 1949. The following season he entered white baseball with the Fort Lauderdale Braves (who moved the franchise and became the Key West Conchs of the Class-B Florida International League). He became one of the first blacks to play in the league.13 In 1951, he performed at both shortstop and third base for the Philadelphia Stars, and then he returned to Key West in 1952. Felder moved to a different minor league as a member of the Pampa Oilers of the Class-C West Texas-New Mexico League for the 1953 and 1954 seasons; he also spent part of 1954 with the Artesia Numexers of the Class-C Longhorn League.

On June 4, 1953, Felder was playing second base for Pampa and was beaned in the second inning by Lubbock pitcher Benny Day and fell unconscious to the ground. The next day’s Lubbock Morning Avalanche provided a detailed account of the frightening incident:

Felder, after regaining consciousness, walked off the field, supported by Oiler teammates, and walked from the dugout to the stretcher.

At the hospital, x-rays showed that he had no fracture and at midnight, he had no headache. He probably will be released today, but probably won’t see action for a few days. The ball hit him high on the crown at the back of his head as he ducked away from an inside pitch, turning his back to the mound.14

Felder returned to the lineup for a game in Plainview three days later.15 He also had a 3-for-4 game against Albuquerque on June 9. Two days later, however, he suffered a broken finger in a pregame workout. A few weeks after returning to action, he was hit in the head by a pregame grounder on August 4 and was removed from that day’s lineup.16

Pampa’s August 19 game was a noteworthy event, but not because of the game itself. The Pampa Daily News explained what the big occasion was:

The first Negro wedding in West Texas-New Mexico League history will take place tonight at Oiler Park where Oiler second baseman, Ben Felder, will wed Miss Irene Boyd in a homeplate ceremony.

The wedding will precede clash between the Oilers and the Amarillo Gold Sox. Time of the wedding has been set for 8 p.m.

The bride-to-be is member of the Carver High School faculty. … Sad Sam Williams, who will pitch tonight’s game for the Oilers, will serve as best man.17

The paper also reported that local merchants were showering gifts upon the couple and that the Oilers’ owner, Doug Mills, was giving them 10 percent of that night’s gate receipts as a wedding gift. In a baseball questionnaire that Felder filled out in June or July of 1953, prior to his marriage to Irene Boyd, he listed his status as “divorced” and stated that his son from his first marriage, Michael, was 2 years old.18 It is unknown how long Felder’s marriage to Boyd lasted or how it ended – since his obituary listed a woman named Miriam as his companion – and it is also unknown whether Felder’s other children all came from their union.

The state of Texas and his marriage both appear to have agreed with Felder in 1953 as he batted a career high .312 with 26 doubles and stole 13 bases.19 Pampa finished in fifth place with a 77-65 record. In spite of the fact that he had been having his best season, by this point Felder appeared to realize that he was unlikely to achieve his goal of making it to the majors. In fact, this is probably the reason why he had shaved five years off his age on his questionnaire, listing his birthday as December 9, 1931. At his actual age of 26, he was not truly prospect material anymore, but if he could convince people that he was only 21, then he might still be given a longer chance to try to develop major-league skills.

Sure enough, notwithstanding the great season he had for Pampa in 1953, the Oilers traded Felder to the Artesia Numexers for infielder Joe Calderon.20 As it turned out, it was reported in March that Felder would be returned to the Oilers because Calderon, who had received a promotion on his “hi-way job in San Antonio,” had decided to quit baseball.21

Although James Riley claims that Felder spent the latter part of the 1954 season with Artesia, game articles and box scores in the Carlsbad Current-Argus show that Felder spent the early part of the season with the Numexers.22 Since it was already certain in March that Felder would be returned to Pampa, it is unknown why he spent any time with Artesia, but he did. Felder played in 23 games for the Numexers, batting .295 with 2 homers and 18 RBIs.23 The Carlsbad newspaper referred to him as Billy Felder, another name by which Benny was known. Brent Kelley explained the confusion, writing, “As a small boy, his playmates called him Billy, and it sort of stuck. As he grew, people came to believe his name must be William. As a result, he was called Billy by some and Benny by others, but for the record, his name is Benjamin.”24

Felder returned to the Pampa Oilers squad and picked up where he had left off the previous season. He is credited with batting .302 with 21 doubles, 6 homers, and 69 RBIs as the Oilers finished with an 81-54 record. Pampa’s season ended as a rousing success on September 23, and Felder was in the Oilers’ lineup for the final time that evening. The Pampa Daily News enthused:

It was all over but the shouting for the Pampa Oilers today after the locals eked out a 3-2 decision over the Clovis Pioneers last night at Oiler Park to nail down the West Texas-New Mexico Shaughnessy Playoff title.

The playoff title gave the Oilers a complete sweep of the WT-NM crowns for the year as the Pampans also won the straightaway flag.25

Longtime Negro League pitcher Jonas Gaines, who had preceded Felder at two of his stops – the Newark Eagles in 1937 and the Philadelphia Stars in 1950 – was the winning pitcher for Pampa in the playoff-clinching game.

Felder began the 1955 season under contract for the Eugene (Oregon) Emeralds.26 His time in the Pacific Northwest was short-lived, however, as the Eugene Guard reported on May 3 that “(t)he Emeralds were forced to release Ben Felder, a fine third baseman, because of an overload of vets.”27 Felder then finished his playing career with the Tampa Rockets of the Florida State Negro League, playing for the team from 1955 through 1957.28

After baseball, Felder returned to the family occupation as a brick mason. He subsequently purchased a service station in Tampa called Billy Felder’s Fina Station.29 Felder did not talk about his baseball experiences much unless prompted. In fact, a 1997 feature article noted, “The young guys who run an auto detail business next to Felder’s shop say they had known him for years before they found out about his professional baseball career.”30 In his later years, Felder was more forthcoming about his experiences as he attempted to educate younger generations about what he and other black players experienced in the Negro Leagues and in the early days of Organized Baseball’s integration. Felder remarked, “There’s a lot of kids who don’t know anything about it. … We caught a lot of hell in our days. We couldn’t stay where the white ballplayers stayed. We had to eat in the back of restaurants. The kids can’t believe it when we tell them.”31

Eventually, bad legs led Felder to have vascular surgery; rather than amputating his right leg, surgeons removed a vein from his left leg and placed in his right leg.32 Later it was reported that he experienced health and financial problems. After suffering a heart attack, Felder struggled with hospital bills and prescription costs. He reportedly lived in a house owned by his brother. At the time he was taking as many as eight prescriptions, including those for his heart, an ulcer, and blood pressure. Eye drops were need for his blurred vision and insulin for diabetes.33

In 2007 Felder was among a number of former Eagles honored at Newark Bears and Eagles Stadium in a tribute organized by the Newark Historical Society. He joined Monte Irvin, James “Red” Moore, and Willie “Curly” Williams in throwing out the first pitch.

Felder died on October 2, 2009, at home in Tampa. Following a funeral at Beulah Baptist Institutional Church, he was buried at Rest Haven Memorial Park Cemetery. He was survived by his longtime companion Miriam, and seven children – Barbara, Shirley, W. Michael, Andre, Billy, Alicia, and Reggie, as well as three siblings, Lela, Booker, and Bobby.34

Notes

1 In his interview with Benny Felder in The Negro Leagues Revisited, Conversations with 66 More Baseball Heroes, Brent Kelley has Felder’s birth date as December 9, 1926, in Tampa, Florida. The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and historian Wayne Stivers also list the same birth date, year, and place. Historians Dick Clark and Larry Lester as well as James Riley give Felder’s birth year as 1925 but with no date. Kelley also notes that many Negro League publications have listed him as William or Billy Felder.

2 Brent Kelley, The Negro Leagues Revisited, Conversations with 66 More Baseball Heroes (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2000), 207.

3 Spellings are as per United States Census data.

4 Kelley, 205.

5 John Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History (Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House Publishers, 2001), 424.

6 Kelley, 205.

7 When asked in 2002 who were the best players he saw during his years in the in the Negro Leagues, Felder responded:

1st Base: Buck Leonard

2nd Base: Larry Doby

Shortstop: Willie Wells

3rd Base: Ray Dandridge

Catcher: Roy Campanella

Outfielders: Willard Brown, Johnny Davis, Monte Irvin, and

Left-handed Pitcher: Pat Scantlebury, Jonas Gaines, and Vibert Clarke

Right-handed Pitcher: Satchel Paige and Leon Day

8 James A. Riley, Dandy, Day, and the Devil (Cocoa, Florida: TK Publishers, 1987), 68-69.

9 “Player Shift,” Newark Star-Ledger, June 6, 1946: 18.

10 Kelley, 206.

11 Kelley, 207.

12 Ibid.

13 Kelley, 206.

14 Joe Kelly, “Hubs Slam Pampa, 12-10, as Fernandez Homers Twice,” Lubbock Morning Avalanche, June 5, 1953: 10.

15 Felder told Brent Kelley that his first game back after the injury came in a return visit to Lubbock. With the bases loaded, he said, Pampa manager Ted Pawalek approached him and asked if he could swing the bat. Recently reunited with his team and elated to be back, he replied, “Yeah, let me try.” He stepped to the plate. “And the Lord helped me. I hit a grand slam home run that night and that was one of the best feelings I had in baseball.” Kelley, 206. We were unable to find any support for this story in any of the Texas newspapers that covered the league. His first game was said to be against Plainview, not Lubbock. Felder also told Kelley that he hit about 12 or 13 home runs a year, but his stats show him with five in 1953 and eight in 1954, so perhaps there was some embellishment involved.

16 “Hubbers Edge Pampa, 12-10,” Lubbock Evening Journal, June 5, 1953: 12; Buck Francis, “Press Box Views,” Pampa Daily News, June 12, 1953: 12.

17 “Wedding at Oiler Park on Tap Tonite,” Pampa Daily News, August 19, 1953: 6.

18 “U.S. Baseball Questionnaires, 1945-2005 for Benjamin Felder,” ancestry.com, accessed January 10, 2019.

19 “Artesia Trades for Ben Felder,” El Paso Times, February 28, 1954: 45.

20 Ibid.

21 Buck Francis, “Press Box Views: Harvester Sprint Relayers Undefeated; Ben Felder to Be Returned to Oilers,” Pampa Daily News, March 28, 1954: 7.

22 “Six Homers Help Artesians Beat Broncs 22-8 in Opener,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, April 21, 1954: 7; “Artesia Belts Wichita Falls by 14-4 Count, Carlsbad Current-Argus, April 25, 1954: 11.

23 Kelley, 208.

24 Kelley, 205.

25 Buck Francis, “Oilers Bring WT-NM Flag Back to Pampa,” Pampa Daily News, September 24, 1954: 7.

26 “Emeralds to Launch Spring Training,” Eugene Guard, April 3, 1955: 28.

27 Dick Strite, “Highclimber,” Eugene Guard, May 3, 1955: 14.

28Wayne Stivers email to W.B. Steverson, February 7, 2018.

29 Taylor Ward, “Leagues of Their Own,” Tampa Bay Times, February 7, 1997: 1T.

30 Ward: 8T.

31 Ibid.

32 Kelley, 207.

33 Dan Steinberg and Dave Sheinin, “Empty-Handed,” Washington Post, August 23, 2003.

34 Obituary, Tampa Tribune, October 8, 2009: 15.

Full Name

William Felder

Born

December 9, 1926 at Tampa, FL (US)

Died

October 2, 2009 at Tampa, FL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.