1966 Atlanta Braves broadcasters

This article was written by Bob Barrier

When the Atlanta Braves began broadcasting in April of 1966, Atlanta area listeners had a long history of baseball radio. Atlanta Crackers broadcaster Ernie Harwell famously had such a reputation in the 1940s that he was traded to a major-league team for a catcher. Because of lawsuits in Milwaukee, the Braves’ move to Atlanta was delayed a year until 1966, but Atlanta Stadium was completed a year early and exhibition games were scheduled to whet the interest of the new Braves fans. During 1965 Milwaukee games were announced back to Atlanta by Mel Allen and Hank Morgan, with Ernie Johnson as color man. Fans naturally expected the famous former Yankees announcer to come to the Braves in 1966 and many wanted Crackers announcer Morgan to be his broadcasting sidekick. This, however, was not to be as the Braves management declined to hire Allen, and Allen himself had been reluctant to move from New York. In addition, Morgan had other duties at WSB (a 50,000-watt clear-channel station with the slogan “Welcome South, Brother.”)1

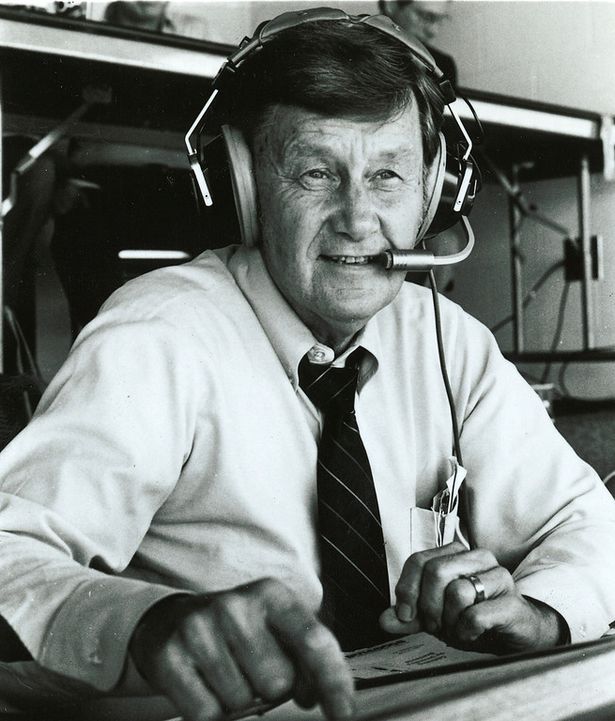

In November of 1965 the Braves announced that well-known journeyman Milo Hamilton, a broadcaster for the Chicago White Sox, would be the Braves’ main announcer. Hamilton was well known in Atlanta since local station WGST had been broadcasting these games for the past four years.2 Hamilton, from Fairfield, Iowa, began his career with the Armed Forces Network on Guam in 1945 and took a degree in radio speech at the University of Iowa. After graduation he spent three years in or near Davenport broadcasting minor-league baseball, local high-school sports, Golden Gloves boxing matches (including 16 matches in one day), and re-creating games, including basketball games involving the Quad City Black Hawks, precursor many years later of the Atlanta Hawks.3

Hamilton broke into major-league broadcasting with the St. Louis Browns in 1953, working with Dizzy Dean and Buddy Blattner. When the Browns moved to Baltimore, Milo lost the job to Ernie Harwell. However, because of his connections with Anheuser-Busch while doing St. Louis basketball, he obtained a secondary position (very secondary) with the legendary Harry Caray in the Cardinals’ booth. Said Caray to Hamilton: “Kid, don’t worry about your mike being on because I am the announcer here.”4 It was the beginning of a lifetime mutual enmity, and Milo lasted only one year with Caray – this time – because Caray preferred a baseball player, Joe Garagiola. After a three-year stint with the Cubs, Hamilton became a nighttime rock ’n’ roll disk jockey for four years in Chicago, until the White Sox and WCFL (a 90-station network) called him to work with boyhood hero Bob Elson, Milo’s favorite broadcast partner. (“What made us a great team, I believe, was that some regarded me as ‘a Bob Elson with enthusiasm,’” Hamilton said.5) Elson was impressed with the massive notes and information that the junior partner fed him. No one has ever said Hamilton shied away from work; by the time he came to Atlanta, he had broadcast, in addition to those White Sox games, Big Ten football and basketball, calling at least 250 games a year between 1961 and 1965.6

Instead of the popular Hank Morgan, the Braves chose Larry Munson as Hamilton’s broadcast partner. Many knew Munson as the broadcaster for Nashville’s Southern Association team and Vanderbilt University football and basketball games. Munson had been a veteran announcer at WSM in Nashville for 14 years. It was a natural for the Braves to choose as their color man Ernie Johnson, who was also a broadcasting executive for the Milwaukee Braves. Clearly, Hamilton was the lead broadcaster, and he always let the other announcers know that.

This broadcasting crew began the season with great popular acclaim and relatively few complaints. The Braves drew tremendously that first season, almost 1,000,000 more than the previous season in Milwaukee. The far-flung Braves network, 36 stations broadcasting games across the US Southeast,7 deserves some of that credit, and even though the Braves went into a nosedive in May, attendance remained at a very high level. In June, the Braves added 18 TV broadcasts, bringing in Dizzy Dean. Old Diz had been fired the previous year when the national Game of the Week changed networks, and now he was back with his famous malapropisms and grammatical errors. Later that year the Braves broadcast several games in color. The booth arrangement for the telecasts, according to Atlanta Journal radio and TV columnist Dick Gray, was for Dean to do the first two innings, Hamilton the third and fourth, Dean the fifth and sixth, Munson the seventh and eighth, and Dean to finish the ninth.8 For the first two years the radio arrangement was that Hamilton did the majority of the broadcasting, picking his innings as he always did, with Munson playing a minor role and Johnson filling in as color.

This broadcasting crew began the season with great popular acclaim and relatively few complaints. The Braves drew tremendously that first season, almost 1,000,000 more than the previous season in Milwaukee. The far-flung Braves network, 36 stations broadcasting games across the US Southeast,7 deserves some of that credit, and even though the Braves went into a nosedive in May, attendance remained at a very high level. In June, the Braves added 18 TV broadcasts, bringing in Dizzy Dean. Old Diz had been fired the previous year when the national Game of the Week changed networks, and now he was back with his famous malapropisms and grammatical errors. Later that year the Braves broadcast several games in color. The booth arrangement for the telecasts, according to Atlanta Journal radio and TV columnist Dick Gray, was for Dean to do the first two innings, Hamilton the third and fourth, Dean the fifth and sixth, Munson the seventh and eighth, and Dean to finish the ninth.8 For the first two years the radio arrangement was that Hamilton did the majority of the broadcasting, picking his innings as he always did, with Munson playing a minor role and Johnson filling in as color.

Writing 44 years later, Hamilton recalled the excitement and enthusiasm of that first year:

“As for me, I worked hard in 1966. I shared the broadcast booth with Larry Munson and Ernie Johnson. We went from booth to booth, changing in the middle innings, so I was doing both radio and TV. It was an interesting transition, to say the least. You could put it all under one banner – the newness kept the enthusiasm going. … More importantly, bringing major-league baseball to the Deep South did wonders for race relations. I don’t think there’s any doubt about it. The advent of the Atlanta Braves also opened doors for other cities, including Dallas, Miami, and Tampa Bay. It expanded the game and created legions of new fans. I felt honored to be part of it.”9

In mentioning the makeup of the crew, Hamilton showed none of the somewhat cynical sarcasm found in his 2006 autobiography, in which he stated that Munson was never prepared for the games and that Ernie Johnson “struck again” in undercutting him when Ted Turner purchased the Braves. Those years in Atlanta, he said, were some of the best times of his life when, for the first time, he made a real big-league salary (primarily because of his many outside-the-booth interests – six o’clock sports on WSB-TV, working for four companies, and over a thousand presentations).10

After the first two games, Dick Gray praised the team: “If you haven’t listened, you’ve missed one of the best broadcasting teams in the country. … Both Milo Hamilton and Larry Munson do an outstanding job. They root for Braves but don’t let their partisan feelings interfere with an impartial description of the events that take place.” Gray added, “There is no flaw that I can find except perhaps that they let Dizzy Dean linger a bit too long when he put in a guest appearance on opening night. … Will listen because I hate to call anyone perfect.”11

This 1966 arrangement lasted two years. In the fall of 1967 Munson was released because his salary no longer fit the broadcasting budget (though the later much-loved Georgia Bulldogs announcer always claimed that Hamilton’s ego was too big to have any other long-term broadcaster in the booth).12 Old Diz stopped broadcasting in 1968. In fact, except for the 12 to 18 TV broadcasts, the Braves radio booth was too full for Hamilton’s liking (even the diminutive Donald Davidson, the Braves longtime traveling secretary, filled in during some ninth innings when games were also on TV).13 Hamilton lasted for 10 years until he too was dismissed because of money problems, declining attendance, and – doubtless but not stated – his supercritical on-air personality. In 1976 Ernie Johnson became the lead broadcaster and Pete Van Wieren was hired as travel manager, replacing Davidson in a bitter scene, and moving into the booth, along with Skip Caray, who had been broadcasting Atlanta Hawks games.14 It was high irony that the son of Harry Caray became a part of the new trio.

This 1966 arrangement lasted two years. In the fall of 1967 Munson was released because his salary no longer fit the broadcasting budget (though the later much-loved Georgia Bulldogs announcer always claimed that Hamilton’s ego was too big to have any other long-term broadcaster in the booth).12 Old Diz stopped broadcasting in 1968. In fact, except for the 12 to 18 TV broadcasts, the Braves radio booth was too full for Hamilton’s liking (even the diminutive Donald Davidson, the Braves longtime traveling secretary, filled in during some ninth innings when games were also on TV).13 Hamilton lasted for 10 years until he too was dismissed because of money problems, declining attendance, and – doubtless but not stated – his supercritical on-air personality. In 1976 Ernie Johnson became the lead broadcaster and Pete Van Wieren was hired as travel manager, replacing Davidson in a bitter scene, and moving into the booth, along with Skip Caray, who had been broadcasting Atlanta Hawks games.14 It was high irony that the son of Harry Caray became a part of the new trio.

Hamilton landed a new broadcasting stint, replacing the Pittsburgh Pirates’ longtime announcer Bob Prince. By 1980, Milo tired of trying to replace a legend and the local sportswriters’ “drinking buddy.”15 Obtaining a job with the Cubs, he was stunned to learn that Harry Caray was to be the lead announcer. After five contentious years, he was again forced out by Caray, only to land with the Houston Astros. In 1992 Hamilton received the Ford Frick Award from the Hall of Fame.16 In Houston, where he spent the longest and most pleasant tenure of his career, Milo retired in 2012 at the age of 84. He had broadcast 7,000 games in 57 ballparks and, perhaps more significantly, had raised over $30 million for charities.17

When Hamilton left the Braves in 1976, Ernie Johnson was able to be part of an amicable and highly popular crew, finally stepping down in 1989 but continuing to do frequent games for Peachtree Cable until 1999. Ernie died in 2011, a much admired and beloved Brave. Skip Caray broadcast through the glory years of the Braves, who won 14 consecutive division titles from 1991 through 2005. Skip’s career was foreshortened by diabetes, complications from which possibly caused his sudden death in 2008.18

The Announcers: Verbal Tics, Personality, and Persona

Milo Hamilton brought a commonly-agreed-on professionalism to the booth. He was always prepared, perhaps over-prepared at the expense of the kind of off-the cuff remarks that made Caray, Red Barber, and Mel Allen popular with listeners. His trademark clichés, even from the first, included such verbal tics as “Holy Toledo,” “a blue star play,” “screaming meemie,” “leaping Lena,’ and “the ballpark will never hold it.” Moreover, he picked up the trait from Midwestern announcers of referring to local fans from small towns who were in attendance – or perhaps never existed at all. This studied exuberance characterized his announcer persona, never more revealing than the history of how his very early “holy mackerel” got him into trouble with Catholics in Iowa until he adopted his father’s mild “Holy Toledo” oath.19

Though Hamilton had experience in announcing historical occasions – 11 no-hitters, Stan Musial’s five home runs in a doubleheader in 1954, the Padres’ Nate Colbert’s similar feat in 1972, and Roger Maris’s 61st home run in 1961 on a re-created broadcast during an off-day game for the White Sox network – he is obviously best known for his broadcast of Hank Aaron’s record-breaking 715th home run. Prodded by writers like George Plimpton to prepare for the historic event since he was certain to call it (having insisted on that the year before), Milo claimed in his autobiography that he refused to “sound contrived” since “spontaneity” was his “strong suit.”20 He did vow to avoid mentioning Ruth while Aaron would be circling the bases, and he did dramatize the moment: “…sitting on 714 … here’s the pitch by Downing … swinging … there’s a drive into left-center. That ball is gonna beeee … OUTTA HERE! IT’S GONE. IT’S 715. There’s a new home-run champion of all time. And it’s Henry Aaron!” Looking back 32 years later, he considered that call the highlight of his broadcasting life.

A comparison of the other two broadcasts of that home run shows that Hamilton deserves his fame. Curt Gowdy of NBC-TV announced the event in an understated way, perhaps letting the visuals carry the excitement. The Dodgers Vin Scully set the scene effectively and detailed the flight of the ball. He stopped for a good 30 seconds, letting the crowd sounds and the fireworks make the statement, but then lapsed into a sociological commentary on race and a crowd cheering a black man in Georgia, fine for the editorial pages or the pulpit but detracting at that point from the baseball moment. Hamilton, in contrast, mixed exuberance and restraint, highlighting the historical event but not overwhelming it.21 Thus, it is Milo’s call that remains the preferred one.

But even here in his most famous broadcasting moment, Hamilton is beset by controversy. The television broadcast that night was by NBC, not the Braves, and Milo called the home run on the radio. Later, he would dub his voice over to the video. And some, as he admitted, thought he “was selfish” in taking control when Aaron was due to bat, though “the fourth inning was mine anyway”: “Maybe Ernie had some qualms about that. But he never said anything to me. Later on, when I went into the Hall of Fame, some writers tried to get him to talk about it, but his quote at the time was, ‘I’ve got no problem with him. He was the No. 1 announcer. It did surprise me a little that he wanted to do it.’ That was the end of that.”22 An exchange that was pure Ernie and vintage Milo. Years later, on the 40th anniversary of the record-breaking homer, April 8, 2014, Hamilton was a significant part of the ceremony honoring Aaron in Atlanta.

By the time of Aaron’s historic home run, Hamilton was becoming more and more a flashpoint for the fans and media. An earlier misunderstanding with Aaron, who thought Milo was unfairly criticizing him, somewhat tarnished the Braves’ 1969 pennant season. A year before, after Larry Munson had left the broadcast booth, the neighboring Marietta Daily Journal opined in its “Around Town” column that “the Braves will find out how valuable Munson was. Hamilton is a good announcer but a hard-sell kind. Listening to him on the radio often reminds me of a hawker at the circus or carnival. The Braves will lose some of their audience.”23 And, in 1975, the same newspaper editorialized under the headline “Milo: Naughty, Naughty, Naughty”: “[W]e are baffled and amused by the outburst the other night blaming everyone except the Atlanta Braves for the misfortunes the team suffered this year. … Milo should look inside the organization rather than blame the fans or the press. We will have to change his nickname to ‘Foot in the Mouth’ [instead of “Mouth of the South”].”24 Others continued to praise Hamilton for his outspokenness but the reputation was wearing thin. When the Braves were sold in 1976, Hamilton was replaced for financial reasons.

Reasons for this lifelong abrasive reputation, despite the generally mellow on-air persona, are not hard to discern. Accustomed to being relegated to secondary (or worse) status in the booth, he later became more and more insistent on being the lead announcer. Even Bob Elson, who had been favorable in the earlier White Sox booth, greeted him when he first came to Houston with the remark, “When you’re here, your microphone will not be on. You will talk in the second half when I don’t talk.”25

The relationship with Harry Caray was apparently one-sided while Milo worked with him. The family man in Hamilton was repulsed by the drinking and womanizing he saw in Caray and others, and the caustic wit of Caray became overbearing, especially when Hamilton was hospitalized with leukemia and Caray indirectly criticized him by saying he himself never missed work, a comment he made several times on the air.26 Milo also was offended by what he regarded as Harry’s egotistic showmanship in leading the crowds singing “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” He refused to stay in the booth during these seventh-inning stretches, lingering on the catwalk as far away as he could.27 When Caray died in 1998, the Cubs placed a statue outside Wrigley Field, and Hamilton said that he wished he could put out peanuts for the pigeons that flocked around the monument.28 Most irritating to Caray’s fans and relatives, especially to Skip, was Hamilton’s mistake, as he termed it, in referring a reporter to a magazine interview he had given in 1985 in which he said that Harry Caray considered himself bigger than the game he was broadcasting. Milo thought no one would reread that interview. When the Internet reporter released those comments from 13 years earlier as if they were current, Skip and others were outraged. Hamilton said that when he met Skip Caray the next spring he tried to apologize but was waved off.29 Others maintain that the two almost came to blows.30

Hamilton’s 2006 autobiography contains a wealth of worthwhile material but it also has many pages of settling scores, essentially damaging to his reputation. But one must grant him consistency in his dislikes, for he states that he got Larry Munson fired because he wanted to work with Ernie Johnson and that Munson, despite his 13 years of experience in baseball broadcasting, never prepared for the games or took them seriously. In 1969 during an unrehearsed call-in show, he said, “Larry Munson is no longer with the Braves because he is not a big-league announcer. To be a big-league announcer one must work at it. You might say that I was directly responsible for his being let go.”31

Fans familiar with Munson’s famous football calls – “sugar dropping from the air,” “ran over him with hob-nailed boots,” etc. – would be stunned to read some contemporary criticisms: “Listening to Larry describe a baseball game was about as exciting as Pat Paulsen describing the action at a wake for a departed St. Bernard.”32 It seems that Munson never had the opportunity to embellish or the confidence to enthuse, being under Milo’s control during those two years with the Braves.33

The same may be said for Ernie Johnson early on. In 1976 a local reporter made this evaluation: “Ernie Johnson, the new chief announcer for the Braves, seems interested enough but often speaks in a monotone and lacks the excitement of Hamilton. The former pitcher will tell you what’s happening but he won’t have the tremendous following that Hamilton did throughout the Southeast.”34 But when introducing the new broadcasting crew, Braves president Dan Donahue said the new announcers were “excellent, each with a distinct and different personality.” Johnson was quoted as saying, “I don’t look at myself as the ‘Voice of the Braves.’ There are three of us and whoever comes up with the best ideas as to how to captivate our audience will get the credit.”35

Writing in 1991, Bob Hope, a Braves public-relations official and vice president from 1966 to 1978, compared Milo and Ernie: Hamilton was a “polished Chicagoan whose resounding voice was matched by an astonishing ego that seemed to clash all too often with players and front office people. His sidekick was a former Braves relief pitcher, Ernie Johnson, who was every bit as down to earth as Milo was high and mighty.”36

Johnson was always the same, “comfortable as an old shoe,” unassuming and mild, the perfect persona for an afternoon game during those long Braves innings in the mediocre ’80s. Pete Van Wieren recalled him saying when a game went into extra innings, “Take the roast out of the oven, Lois, I’m going to be a little late.”37 His love of family, the Marines, and the game itself came through even to fans who listened casually. Having a 50-year career with the Braves in three cities and many roles made him the quintessential team player. On September 2, 1989, an Ernie Johnson Appreciation Night drew 42,000 for a team that normally averaged around 12,000. Writing two days later, a local reporter pointed out how the next game, Ernie’s final as a WSB Braves announcer, had only several hundred in attendance. “He was in his element and unmistakably happy. He is leaving with grace and ease which are his trademark … a broadcaster who never had many silly trademark phrases, never became a regular on the talk shows, never danced in a beer commercial … who talks to you like your favorite uncle.” “Got a letter,” Ernie said, “from a farmer. Farmer said he never missed a pitch even when he milked his cows: He hung the transistor on a spike; he said it sounded about like you’re talking right to me while I was milking the cows.”38

It was this quiet professionalism that made the occasional humorous remark special, as in 1987 when the national press quoted Ernie’s joke about a fly ball bringing down a bird: “After Dion James’ fly ball hit a pigeon in Shea Stadium, Johnson said, ‘Every statue in New York is smiling right now.’”39

Johnson continued as a part-time Braves announcer for 10 years, doing some games for WPCH Peachtree Cable, working occasionally with his son, Ernie Jr. When he died after a long illness, the outpouring was immense. Mark Bradley of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution wrote that Ernie was the “nicest man who ever lived, all sweetness and light, with a voice a wondrous amalgam of New England – on the air he was pure magnolia. If Ernie uttered an unkind word, I never heard it.”40 And Bradley’s colleague Carroll Rogers related that Ernie Jr. “stumbled onto one of his father’s favorite signoffs – ‘This is Ernie Johnson and on this winning night, so long everybody.’” Rogers concluded her memorial column with the comment that Ernie Jr’s “knees buckled when he read this online tribute – ‘When you heard Ernie Johnson do a game, it was like … summertime would never end.’”41

The Braves’ 1966 season began that April night, with Milo Hamilton exclaiming, “Big-league baseball has come to the South”42 and Tony Cloninger firing a fastball high outside to the Pirates’ Matty Alou to start a game that ended in a disappointing loss in 13 innings. Nevertheless, despite a fifth-place finish, the fans, if not some of the press, remained enthusiastic and hopeful. That interest came from the uniqueness of live major-league ball and the daily broadcasts. Though they were not yet “America’s Team” of cable television fame, they became immediately the Southeast’s team. Milo Hamilton would leave Atlanta having announced for only one division pennant winner but having become celebrated for one historic moment; Ernie Johnson would stay to see eight division championships, and Larry Munson would gain fame – and a national football championship call – from the Bulldogs booth.43 It was a good start.

Other sources

Smith, Curt. Voices of Summer: Ranking Baseball’s 101 All-Time Best Announcers (New York: Carroll & Graff, 2005).

SABR, The National Pastime. sabr.org/content/the-national-pastime-archives).

Notes

1 Dick Gray, “Gray Matter,” Atlanta Journal, May 26, 1966: 78.

2 “Hamilton, Chi Broadcaster, To Head Atlanta Air Team,” The Sporting News, November 13, 1965: 9.

3 Milo Hamilton, Dan Schlossberg and Bob Ibach. Making Airwaves: Sixty Years at Milo’s Microphone (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publications, 2006), 28-31.

4 Hamilton, 39.

5 Hamilton, 62.

6 Gray, April 14, 1966: 84.

7 “Log of Play-By-Play Broadcasts and Telecasts, From National League Cities for 1966,” The Sporting News (April 16, 1966): 29.

8 Gray, May 13, 1966:16.

9 Milo Hamilton, as told to Dan Schlossberg, “Milo’s Memories: When the Braves Came to Atlanta,” in The National Pastime (Society for American Baseball Research, 2010) Retrieved from online archives on April 19, 2014.

10 Hamilton.

11 Gray, 84.

12 Larry Munson with Tony Barnhart. From Herschel to a Hobnail Boot: The Life and Times of Larry Munson. (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2009). Kindle Edition. Location 823 of 2142.

13 Bob Hope, We Could Have Finished Last Without You: An Irreverent Look at the Atlanta Braves, the Losingest Team in Baseball for the Past 25 Years (Atlanta: Longstreet Press 1991), 31.

14 Pete Van Wieren with Jack Wilkinson, Of Mikes and Men: A Lifetime of Braves Baseball (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2010), 33-34.

15 Hamilton, 87.

16 Despite the ego and the controversies, Hamilton was recognized by Atlanta sportswriter Glenn Sheeley: “Resonance. Spontaneous delivery. Clarity. Baseball knowledge. That’s been the scouting report during a broadcasting career that’s covered 39 years. And that’s probably the best testimony to his induction.” Glenn Sheeley, “Holy Toledo! Milo’s Headed to the Hall,” Atlanta Journal and Constitution, August 2, 1992: G4.

17 Pat Hughes, Baseball Voices: “Milo Hamilton: A Call for the Ages.” 2009 (http://baseballvoices.com).

18 The specific causes of his death were never announced, although he had been suffering from diabetes, congestive heart failure, and reduced liver and kidney functions.

19 Hamilton, 143-144.

20 Hamilton, 73.

21 Three Different Calls to Aaron’s 715th Home Run (http://archive.org/details/HankAaron-715thHomeRun-ThreeDifferentCalls).

22 Hamilton, 73.

23 Bill Schemmel, “Around Town,” Marietta Daily Journal, March 22, 1968: 4.

24 “Milo: Naughty, Naughty, Naughty,” Marietta Daily Journal, July 9, 1975: 4.

25 Hamilton, 160.

26 Hamilton, 102.

27 Hamilton, 104.

28 Hamilton, 103.

29 Hamilton, 115-116.

30 See I.J. Rosenberg, “Skip Caray’s reaction to Hamilton: ‘Sick man,’” Atlanta Journal, February 21, 1998: G03, and comments to John Royal, “Astros Broadcaster Milo Hamilton to Retire, Finally,” Houston Press Blogs, February 15, 2012, (blogs.houstonpress.com/hairballs/2012/02/milo_hamilton_to_retire.php). Thomas Stinson states that “there were fears within the club that an incident might ensue when the two finally crossed paths.” However, “nothing happened.” Thomas Stinson, “Braves Notebook,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, March 8, 1998: E04.

31 Horace Crowe, “Winging Sports,” Marietta Daily Journal, June 19, 1969: 9.

32 Len Gilbert, “Let’s Talk Business,” Marietta Daily Journal, April 7, 1968: 9.

33 In From Herschel to Hobnail Boots, Munson relates about the firing that Milo had an agent –and he did not – and that he should have “told the Braves how I felt, but I didn’t bother to do it at all.” When told by the Braves that he was being released, Munson said, “You mean I’m out and that son of a bitch has survived?” Location 870 of 2142.

34 Mick Walsh, “Pro Jocks ‘Cloud’ TV Sports Picture,” Marietta Daily Journal, March 14, 1976: 23.

35 Mike Webber Johnson, “Atlanta Braves Looking for a Winning Season,” Marietta Daily Journal, December 4, 1975: 32.

36 Hope, 31.

37 Van Wieren, 150.

38 Robert Byrd, “Braves Announcer Ends Career,” Marietta Daily Journal, September 11, 1989: 3b.

39 The Sporting News, April 27, 1987: 28.

40 Mark Bradley, “Unrivaled Southern Gentleman,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, April 14, 2011: C3.

41 Carroll Rogers, “A Lifetime of Admiration,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, April 14, 2011: C3.

42 Lewis Grizzard, “For Atlanta fans, it was worth the wait,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, October 21, 1991: A1.

43 Larry Munson did return to the Braves broadcasting booth one last time – more than 30 years later. Because announcer Don Sutton was being inducted into the Hall of Fame on, July 16, 1998, and fellow announcers Skip Caray, Pete Van Wieren, and Joe Simpson were accompanying him, Munson and Hawks announcer Steve Holman did the game in Pittsburgh against the Pirates. Munson said, “The last baseball game I did was the first week in October of 1967. … I haven’t even done a Little League game. I had to turn on the TV the other night to see how the diamond looked.” Prentis Rogers, “Munson to call Braves for WSB,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, July 25, 1998: G01.