October 1866: A return on their investment

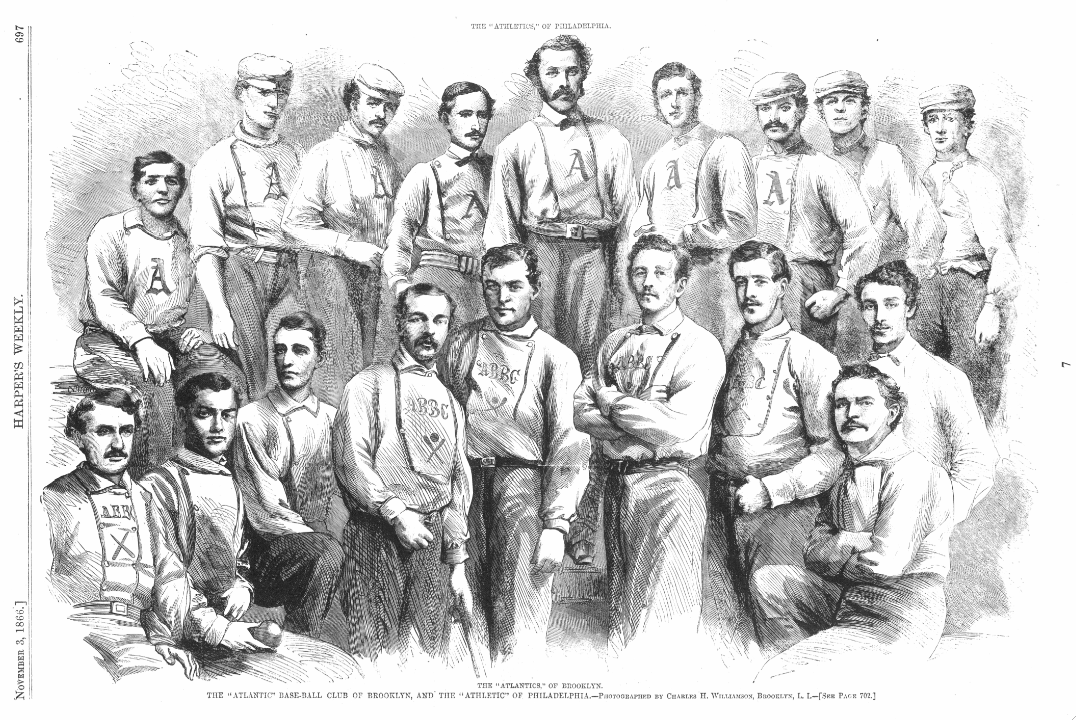

The Brooklyn vs. New York All-Star series held in Flushing during the summer of 1858, the first to charge the spectators admission, had proved that the public was willing to pay to watch important and high skill-level baseball. That series led clubs to take strong measures to obtain the best players so they could derive the most return on their investment. The October 1866 series between the Athletics of Philadelphia and the Atlantics was, to that point, the culmination of enticing players, arranging tours, promoting matches between top clubs, and charging the public, all to maximize profit.

The first game of the series was to be played on October 1 at the Athletics’ grounds at Columbia Avenue and 15th Street. Crowds began gathering downtown early on the day of the game, with newspapers reporting the advance sale of 8,000 tickets at 25 cents apiece, 2½ times the normal 10-cent charge.[fn]Orem, Preston D. Baseball 1845-1881 From Newspaper Accounts, p. 52.[/fn] There were reports of speculators offering the team as much as $5 for reserved seats, anticipating that they could resell them at a profit, only to be turned down by Athletics management.[fn]Ryczek, William. When Johnny Came Sliding Home ( Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1998), p. 95.[/fn] For perhaps the first time, 5-by-4-inch printed fold-over scorecards were handed out. Betting was extremely heavy and the hometown club was slightly favored. Bets estimated to total $5,000 were placed.[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

The first game of the series was to be played on October 1 at the Athletics’ grounds at Columbia Avenue and 15th Street. Crowds began gathering downtown early on the day of the game, with newspapers reporting the advance sale of 8,000 tickets at 25 cents apiece, 2½ times the normal 10-cent charge.[fn]Orem, Preston D. Baseball 1845-1881 From Newspaper Accounts, p. 52.[/fn] There were reports of speculators offering the team as much as $5 for reserved seats, anticipating that they could resell them at a profit, only to be turned down by Athletics management.[fn]Ryczek, William. When Johnny Came Sliding Home ( Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1998), p. 95.[/fn] For perhaps the first time, 5-by-4-inch printed fold-over scorecards were handed out. Betting was extremely heavy and the hometown club was slightly favored. Bets estimated to total $5,000 were placed.[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

While 8,000 ticket-holding spectators would have been a manageable crowd, Philadelphia was unprepared for what actually developed by game time. Another 22,000 to 32,000 people showed up, causing chaos inside and outside the grounds. Preston Orem later described housetops for blocks around the playing grounds, trees, fences, and other prominences all “covered with a dense mass of human beings.”[fn]Orem, p. 52.[/fn] There were more people outside the playing field than inside, and those on the field were crammed together, constantly jostling for a view.

The Athletics, batting first and therefore striking a fresh ball, scored on consecutive home runs by pitcher Dick McBride and second baseman Al Reach. In the bottom of the first inning, the Atlantics had Charles Smith on third base and Joe Start on first base with one “hand” out when the excitement overtook the crowd. “Crane was next to bat, but before he had a chance to strike the game was stopped to allow the crowd to be cleared from left field,” the New York Times correspondent reported.[fn]New York Times, October 2, 1866, p. 1.[/fn] Triggering the commotion was a scuffle between a fan and the police.[fn]Ryczek, p. 95.[/fn] For about half an hour, efforts to push back the crowd failed, and eventually the game had to be called.[fn]New York Times, op. cit., loc. cit.[/fn]

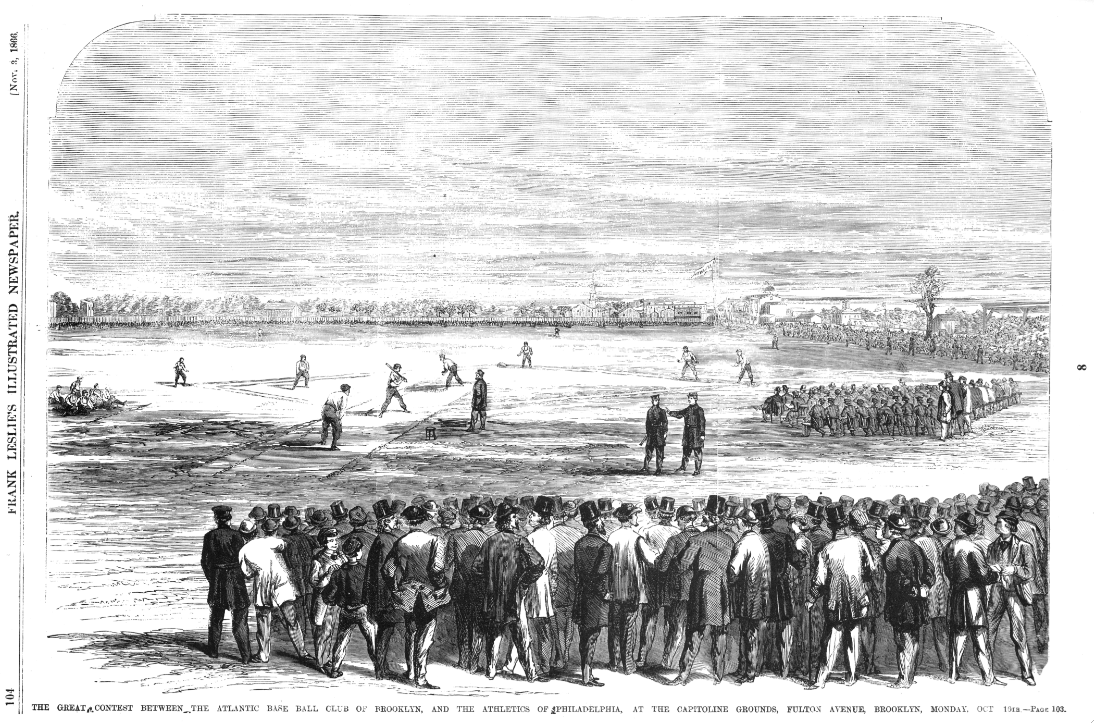

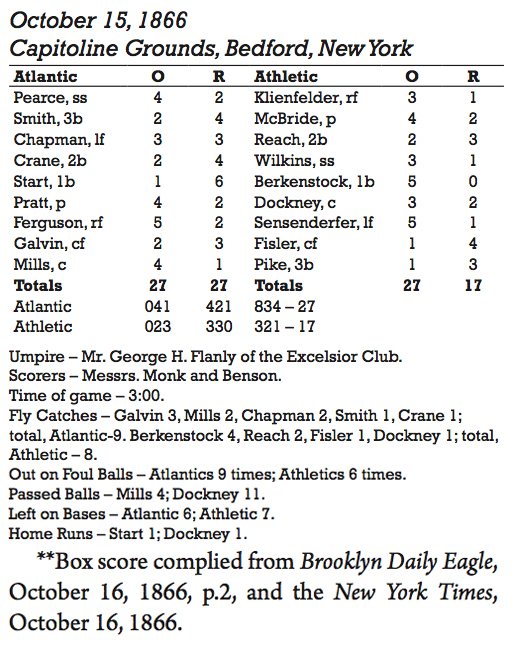

Officials decided to reschedule the contest for October 15 at the Capitoline Grounds in the Bedford section of Brooklyn.

Officials decided to reschedule the contest for October 15 at the Capitoline Grounds in the Bedford section of Brooklyn.

Capitoline Grounds, home of the Atlantics in 1865, seemed better suited to crowd control than the grounds in Philadelphia. It was “bounded on three sides by board fences and on the fourth side by a high stretch of gate work running parallel with the road leading to the highway and the cars.”[fn]Orem, p. 53.[/fn] No tickets were sold in advance for this match, reported the New York Tribune, which added that spectators arriving on game day should have their quarters ready, as no change would be made. Seven entrances were manned by 18 ticket-takers,[fn]New York Tribune, October 5, 1866, p. 8.[/fn] proprietors Reuben S. Decker and Hamilton A. Weed wanting to ensure that they collected from all those who entered that historic day.

The spectators began arriving before 10 a.m. for the scheduled 2 o’clock match. The 4,000 available seats were quickly filled and by 11 a.m., possibly as many as 20,000 had encircled the playing grounds.

Employing burly policemen was paramount in retaining order, which was Brooklyn’s priority. In spector John S. Folk ensured that the debacle in Philadelphia would not be repeated. He and 152 captains, sergeants, officers, and patrolmen from 10 precincts arrived at the grounds at 11 a.m. to maintain order.[fn]New York Times, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 16, 1866.[/fn] Even though the spectators encircled the field, not one incident was reported.

The Athletics tied the match 11–11 in the fifth inning, but the Brooklyn club scored 16 runs over the last four innings and won 27–17.

The match itself failed to achieve the status of one of the greatest played in baseball’s infancy. But the event was without question the greatest day of baseball in North America to date. No game had attracted so many to Capitoline Grounds, required as large a police presence and produced the amount of attendance revenue, estimated at more than $1,000.

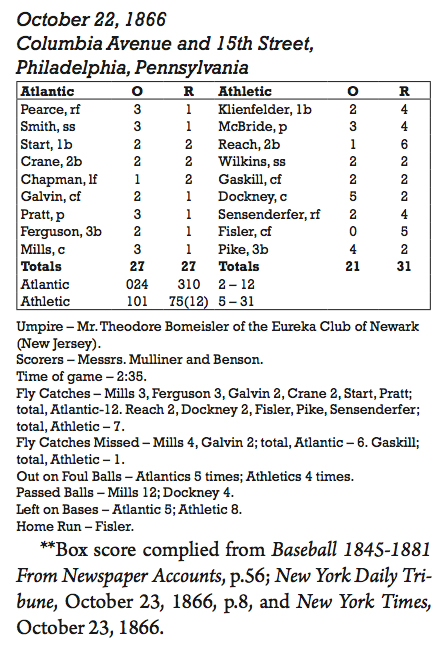

The Athletics made it known that Philadelphia police would be represented generously to maintain order at the October 22 return match. They had a fence erected around the field, at the cost of $1,500. They also reduced the number of spectators to a relatively minuscule 4,000. To make certain that a substantial profit was made and perhaps to cover the expenses, the Athletics charged $1 per ticket, an extraordinary amount for baseball in 1866 and four times what had been charged for the first contest.

Between 2,500 and 5,000 spectators paid for the game, the Times also reporting that “all the surrounding houses, trees, high ground and vehicles were crowded with spectators making the scene one of great animation.”[fn]New York Times, October 23, 1866.[/fn]

The contest was even through four innings, at nine runs apiece. This time it was the Athletics’ turn to enjoy a blowout as they outscored the Atlantics 22-3 in the next three innings, taking a commanding 31-12 lead. As the Atlantics batted in the top of the eighth, the rain began to fall heavily, forcing the umpire to call the match at 4:45 P.M. The build-up had again been more exciting than the match.

Immediate allegations of the Atlantics lying down to ensure a third payday were abundant. These were not cynical views. Simply based on the financial take from the two-plus matches, the bare minimum that the two clubs were to share was $7,000. A third and deciding match would have easily pushed the coffers to more than $10,000.

But before splitting the gate receipts, the Athletics had to account for the $1,500 it cost to erect the fence around their playing field. They also accounted for the fact that they paid all of the traveling expenses of the Atlantics to Philadelphia, and that the Atlantics did not do the same for them.[fn]Ryczek, p. 96.[/fn]

The Bedford club, however, insisted on their share being based on the gross amount. The resulting stalemate ruined the momentum that the two previous matches achieved in terms of money-making ability, spectator interest, and the declaration of an undisputed NABBP Champion. The games did prove that high-level baseball was a viable business and, simply based on that thought, it is unconscionable that the two would not allow a third match.

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Additional Stats

Atlantics of Brooklyn vs.

Athletics of Philadelphia

At Philadelphia, PA; Brooklyn, NY

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.