Joe Start

There have been countless cosmetic changes in how baseball has been played during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, but the tools and rules of the game — and of the professional sport — have not been radically altered. A spectator from 1901 would recognize the game in 2021. The revolutionary advances occurred in the 19th century when baseball evolved from a loosely structured children’s pickup game to a crowd-cheering stadium sport. Many amateurs taking the field in the 1850s could not stay current with — and play well under — the drastic changes in rules, equipment, professionalism, and terminology over the ensuing decades.

There have been countless cosmetic changes in how baseball has been played during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, but the tools and rules of the game — and of the professional sport — have not been radically altered. A spectator from 1901 would recognize the game in 2021. The revolutionary advances occurred in the 19th century when baseball evolved from a loosely structured children’s pickup game to a crowd-cheering stadium sport. Many amateurs taking the field in the 1850s could not stay current with — and play well under — the drastic changes in rules, equipment, professionalism, and terminology over the ensuing decades.

There were short-term exceptions, but perhaps no one weathered these upheavals with sustained skill like Joe Start. Over Start’s career he witnessed numerous innovations that transformed the game in fundamental ways, but he adjusted and continued to play at a superior level for over 25 years.

Historian Bill Ryczek vividly summarized Start’s odyssey:

“When 16-year-old Joe Start began playing in 1859, pitchers threw underhand with a stiff wrist from behind a line 45 feet from home plate, a fly ball caught on one bounce was an out, and gloves were unheard of, as were professional ballplayers. During his final season [1886], pitchers threw over-hand or sidearm with velocity that was unimaginable in 1859. The [fair] one-bounce out was 20 years in the grave, and most players wore fielding gloves. All of the top players were professionals, and baseball had become big business, far removed from the amateur affair of 1859. Despite the dramatic changes in the game of baseball, Joe Start remained a steady, productive player, adapting to the changes as quickly as they appeared. He was a regular until his final year.”1

Historian Peter Morris called Start “a forgotten superstar who remained the standard for first basemen from the early 1860s until his retirement in 1886.”2 Sportswriter William Rankin, in 1910, asserted: “It was Joe Start who made first base a fielding position. Up to the early [1860s] the first baseman stood at the base and caught … all balls thrown there, but made no attempt to leave the base to get batted balls. … Start revolutionized the first base system of play.”3

Because of his solid sportsmanship, mature temperament, leadership ability, and longevity, Start earned the nicknames Old Reliable and Old Steady4 (and by the 1880s, often simply “Old”). He was renowned as a man of honor and a player of impeccable integrity.5 In an era when drunkenness, gambling, and club-jumping threatened to destabilize the game’s organizational growth, Start was never blemished with a hint of scandal.

According to an item in the Brooklyn Eagle in October 1864, “[T]here is no better player in [sic] the [Atlantic] club, and none who so uniformly marks his play in matches with conduct which is worthy of a gentleman ball player. Under the most exciting circumstances we have never seen him lose his temper or forget himself in any way, and in his quiet way of doing things he is quite a model for the growling fraternity.”6

That reputation endured. An 1873 Eagle late-season glimpse at player commitments for 1874 declared, “We notice the names of Joe Start … and a dozen more of the same class, whose record … is unstained with the slightest suspicion of knavish play. These players find their best capital in their honest record.”7 An 1879 New York Clipper profile said that after 20 years of play, “not the breath of suspicion has tarnished the bright escutcheon of [Start’s] reputation as an honest player.”8 And in 1882, the Eagle again: “There is one professional player in the league, whose word is as good as his bond, and that is Joe Start.”9

Batting and throwing left-handed, Start stood 5-feet-9 and weighed around 165 pounds.10 Although primarily a first baseman throughout his career,11 he appeared in the outfield in five of his 1,074 major-league games.12 Start’s fielding skills were praised in 1869 by the Clipper as “easy, graceful and sure.”13 Playing in an era before gloves existed, Start also became adept at catching bad infield throws. In 1871 the Clipper observed, “Start is very effective in taking in low balls, as well as those thrown in over his head, and the hotter they come the more securely they appear to be held.”14 Outfielder Jack Chapman, one of Start’s 1860s teammates, told the Eagle in 1896 that he “never saw a man play first base like him during all his years in base ball. Start did not hug the bag … but got off and back again with phenomenal quickness. In this way, he saved many an error for the infielders.”15

Although born when baseball was a social club-based leisure pursuit, had no press coverage, and was unknown outside of New York City, Start — who died in 1927 — lived long enough to see the worldwide acclaim for slugger Babe Ruth. Three years later, John J. O’Brien, longtime caretaker of Brooklyn’s Parade Grounds, in a 1930 profile by the Eagle, recalled his own youth as a sandlot player and commented, “I was called Joe Start. The original Joe was with the old Atlantics. He was the Ruth of his day.”16

Not quite. Start was never a dominating, explosive superstar like Ruth. But a case could be made that Start was the Cal Ripken Jr. of his day: dependable excellence over an extraordinarily long career. Except that Ripken did not have to deal with the game’s basic rules being overhauled from season to season.

Ryczek said that Start “was the last of the pre–Civil War players to hang up his cleats.”17

Joseph Start (he had no middle name)18 was born on October 14, 1842, in Brooklyn, New York. The fourth of 12 children born to Hannah Ann (nee Roff) and fishmonger Michael Start,19 Joe attended the Bedford Avenue and Monroe Street Elementary School.20 Start began playing team ball with the young, amateur, and highly competitive Enterprise Club of Brooklyn in 1859,21 before the formation of organized leagues. He stayed with the Enterprise through 1861. (That year many established clubs were dormant as players enlisted to fight in the Civil War. There is no indication that Start enlisted.) In 1862, along with Enterprise teammates Jack Chapman and Fred Crane, Start was recruited and signed by the dominant Atlantic Club of Brooklyn.22 (The Atlantics were founded in 1855 and their competitive superiority extended back to 1856.23)

Start would remain with the Atlantics through the 1870 season. This decade proved decisive in elevating baseball from a game to a sport; what participants were playing on the field in 1870 was markedly different from what had been played a decade earlier. The Massachusetts game (with five bases) was superseded by the New York game. The rules became more systematic. In the late 1850s, the pitcher was a butler who served the ball to allow the batter to hit it and commence the on-field excitement (hitting, running, and fielding); by 1870, the pitcher and batter were mortal enemies, the ball weaponized.24

The Atlantics were undefeated in 1864 and 1865.25 During this decade, unofficial payment for exceptional players became common and the practice was eventually legitimized. Start claimed he began receiving payment around this time. In an 1895 interview by Tim Murnane, Start recalled his early days: “I think every one of the Atlantics was a kid. They may not have had the game down so fine as now, but there was a good deal more honest enthusiasm about it. Indeed, for a few years at least, we could hardly have been called professionals. We didn’t get any salaries, I remember very well, for three or four years.” Start said that Atlantic players began receiving salaries “about 1866, as near as I remember.”26 (And by “salaries,” Start meant a percentage of the gate, not a fixed cyclical wage.27)

Before the advent of salaries, supporters of the Atlantics had recognized the value of Joe’s performance to the Brooklyn community. In October 1864 a benefit game was held to raise money for him,28 the Eagle reporting, “Like a good son and an affectionate brother he supports a [widowed] mother and sisters.”29 (Joe’s dad, Michael, had died in May 1860 at age 45.30)

The Atlantics during this transitional pre-league decade featured some of the most capable players of the era: Dickey Pearce (1857-1870), Bob Ferguson (1866-1870), Lip Pike (1865), George Hall (1870), and George Zettlein (1866-1870), all of whom went on to play in the majors. (Hall was banished in 1877 after being embroiled in a gambling scandal.) None except Pearce were with the Atlantics longer than Start.

If consistently playing for winning teams makes one a winner, the Atlantics’ won-lost record (according to historian Marshall Wright31) with Start on the roster is Exhibit A:

- 1862: 2–3

- 1863: 8–3

- 1864: 20–0–1

- 1865: 18–0

- 1866: 17–3

- 1867: 19–5–1

- 1868: 47–7

- 1869: 40–6–2

- 1870: 41–17

- 212 games won, 44 lost, four tied. That is a team winning percentage of .828 — over nine years (a 162-game equivalent of 134 victories).

Start made a pivotal contribution to one of the most celebrated games of baseball’s pre-league era. The all-salaried Cincinnati Red Stockings had 81 consecutive wins across two seasons when they faced off against the Atlantics on June 14, 1870, before an estimated 20,000 fans “in and around [Brooklyn’s] Capitoline grounds.”32 After nine innings, the game was tied 5-5. The Atlantics were inclined to accept the draw. (The rules at the time did not mandate extra innings; tied outcomes were not uncommon.)33 However, Cincinnati’s Harry Wright insisted on completion of the match,34 and umpire Charlie Mills ordered the teams back on the field.35

In the top of the 11th, the Reds scored twice to take the lead, 7-5. In the bottom of the 11th, Atlantics third baseman Charlie Smith singled. Start then hit a booming triple “beyond the reach of [Cal] McVey at right field,”36 scoring Smith. Catcher Bob Ferguson drove in Start with a single to tie the game, 7-7. With one out and runners on first (Zettlein) and second (Ferguson), what happened next is the subject of historical disagreement — although all concur that it brought victory to the Atlantics. There are a number of contradictory chronicles, but let’s go with one: George Hall hit a grounder to second baseman Charlie Sweasy, who booted it; Ferguson made a dash for home and scored when Sweasy made an errant throw to the plate,37 thus ending the Red Stockings’ historic streak.38

At age 27, when most premier players are in their prime, Start already had 12 statistically untabulated seasons under his belt. The anno domini of major-league stats is 1871; before that year, any numbers are largely speculative. We have only journalistic accounts and player remembrances attesting to Start’s high caliber of play during the Amateur Era.

In 1871, when full and open professional competition took root with the inauguration of the National Association (NA), the Atlantics opted to revert to amateur status.39 Start was determined to remain a pro.40 His services, along with those of Atlantics infielders Bob Ferguson and Charlie Smith, were sought by three NA clubs: the New York Mutuals, the Philadelphia Athletics, and the Chicago White Stockings. Talks were held, terms were offered, and negotiations ensued, but the deciding factor was that “Joe Start did not want to leave home, and Charley [sic] would not go outside of New York either.”41 So all three joined the Mutuals, as did Atlantics shortstop Dickey Pearce. That year Start hit a career-high .360, second highest on the Mutuals behind Dick Higham, who batted .362. Start hit the team’s only home run.42

In 1873 he served as the team’s field leader for 25 games. His record as manager was 18-7. That same year, indicative of his on-field smarts, Start pulled off a variation of the hidden ball trick on his former Atlantics teammate Lip Pike, then playing for the Baltimore Canaries. According to the Eagle, in the sixth inning:

“Pike overran first base, and in passing it was touched by Start with the ball, but the umpire, Mr. N. Young, decided the player entitled to his base [i.e., safe]. Start, however, held on to the ball, and performed as clever a piece of base ball generalship as could be wished for. He argued with Pike that he had been put out, whereupon Pike left his base for the purpose of explaining how he had overrun the base, and no sooner had Pike stepped from the sand bag then the wily Start touched him with the ball, thus putting him out, and it was so declared by the umpire. It is not often Lip gets caught napping in this style.”43

The NA failed after five years. Contributing to its demise was the pattern of weak teams not finishing their committed season schedules, a trend aggravated by the league’s lack of disciplinary authority and by financial shocks following the Panic of 1873. When the more tightly reined National League debuted in 1876, the Mutuals were one of eight charter teams, and Start remained with the club. However, the Mutuals were a poor team that year (21–35, sixth place), and after refusing to embark on a final road trip because bankruptcy beckoned, they were expelled from the NL. (The Philadelphia Athletics were dropped for the same reason, leaving the NL a six-club circuit.) Over the course of the Mutuals’ six-year professional existence, Start was the team career leader in games, at-bats, hits, runs, doubles (tied), home runs, and RBIs.

At some point in the 1870s, Start, like many first basemen of the era, began wearing a makeshift glove. In a 1912 interview, he recalled, “My mitt was fingerless and simply had a heavy pad over the palm of the hand to save the flesh from being torn apart when the ball was jumped at me from a short distance and speed was necessary by the fielder in order to get the man bearing down on the bag.”44

After the demise of the Mutuals, Start joined the former Hartford Dark Blues, who had relocated to Brooklyn to become the Brooklyn Hartfords. The 1877 Hartfords — managed by Start’s former Atlantics teammate Bob Ferguson — played their home games in the same ballpark, the Union Grounds, in which the Mutuals had played in 1876. Start posted the second highest batting average on the team (.332), behind John Cassidy (.378). But after finishing in third place, the Hartfords disbanded.

In 1878, after almost 20 years of playing exclusively for Brooklyn-based teams, Start signed with the Chicago White Stockings, a club owned by NL President William Hulbert. In what was possibly his best season at the plate, Start played in all of Chicago’s 61 games and led the league with 285 at-bats, 100 hits, and 125 total bases.45 His batting average was .351, tying him for third in the NL with teammate Bob Ferguson, and his 58 runs scored were second. These marks were achieved at age 35, by which point most late-nineteenth-century players had faded, retired, or expired.

However, Start apparently was unhappy playing for Chicago. According to an 1879 profile marking his farewell from the team and his hiring by the Providence (Rhode Island) Grays, “One season’s play under Hulbert’s management was enough for Joe. He refused to stay longer.”46

When Start joined Providence, the team was managed by early baseball pioneer George Wright (an adversary in the Atlantics’ 1870 upset of Cincinnati).47 From 1879 until 1885, when he was 42, Start patrolled first base for the Grays and continued to hit well, averaging .298 during those seven years. He also served as team captain, a role that provided field leadership.48

In 1879 Start sparked a chain of events that resulted in a breach (however brief and temporary) of the major-league color line — although he never knew it. The NL had a de facto prohibition against hiring African American players. On June 19 Start “broke the second finger on his left hand.”49 For the Grays’ next match, on June 21, Start’s one-game replacement was William Edward White, a local standout for the Brown University squad.50 In White’s only major-league game, he handled 12 chances at first without an error and got one hit in four at-bats. (Grays right fielder Jim O’Rourke anchored first base for the remainder of Start’s absence.)

In the early twenty-first century, SABR researchers confirmed that White, the son of a white Confederate soldier and one of his slaves, was the first African American to appear in a major-league game.51 That year Providence captured the NL flag. (White deserves some credit: The Grays beat Cleveland 5-3 on the day he played, giving White as a player a lifetime W-L percentage of 1.000.)

Start’s value to Providence was well documented in the local press.52 According to a biographical sketch by Rick Harris in Rhode Island Baseball: The Early Years, Start’s “value was also demonstrated in monetary terms. The entire payroll for the Grays in 1881 was $13,175. Start’s salary of $1,600 was second only to that of pitcher John Montgomery Ward, who topped the team at $1,700.”53

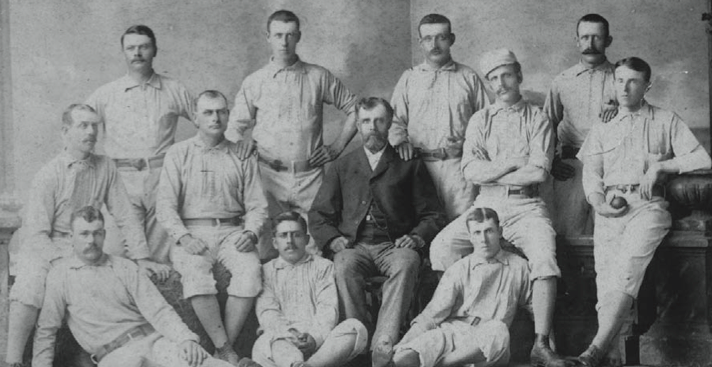

1882 Providence Grays. Joe Start is pictured in the middle row, second to the left.

Though six years gone from New York, Start remained popular in Gotham. Before Brooklyn (the Trolley Dodgers, unrelated to Start’s former team the Atlantic) faced off at home against Providence on April 19, 1884, the squad “marched up to Captain Joe Start and presented him with a handsome basket of flowers as a personal compliment to his high character as a player … the veteran being loudly applauded as he received the gift.” The respectful gesture was repaid by Start’s Providence team trouncing Brooklyn 15-0, a rout the Eagle termed a “Waterloo defeat.” The story further opined, “Probably the home team thought the affair could not be completed without they gave Joe the game too.”54

In 1884 Providence, propelled by the iron arm of pitcher “Old Hoss” Radbourn,55 who logged 60 victories with only 12 losses, won what is considered the first interleague championship (i.e., a World Series before the concept existed), beating the New York Metropolitans of the American Association.56 Start had another decent season at the plate, batting .276 (second highest on the team), although he played in only 93 of the team’s 114 games. In the series against the Mets, Start was lackluster at the plate (one single in 10 at-bats), but he was reportedly weakened from the residual effects of a summer bout of malaria.57

After the series triumph, manager Frank Bancroft recalled in 1892, “[O]ld Joe Start and I chartered one of those organ grinders and loaded him into an open hack. Then we had a little procession up Michigan avenue. Our line of march was quite an extensive one, and we spent half the night on the go listening to the squeak of ‘Captain Jinks’ and the other melodious chestnuts in the repertoire. On the streets the people regarded us as wild species of lunatics, but we were celebrating and happy.”58

Though Joe was keen on continuing to play for Providence, the club left the NL after a disappointing 1885 season (53–57, fourth place), leaving Start professionally homeless. Ryczek notes, “In an era known for its revolving [players switching teams], Start, with the exception of leaving Chicago after the 1878 season, stayed with his team until there was no more team.”59 An 1879 profile noted that “Joe was never much of a rambler from one club to another.”60

Start signed with the Washington Nationals in 1886 for what proved to be his final season.61 The Nats were an abysmal team. (They eventually finished last in the NL with a pathetic 28–92 record.) Start played in only 31 games, was unhappy there, did not hit well, batting only .221, and was released on July 12,62 having played his final game on July 9.63 The Providence Journal wrote, “Joe Start, like an old race-horse, has been turned out to grass. Joe has returned to Providence, where he intends to remain for the present.”64 Joe still wanted to be on the diamond. According to the Brooklyn Eagle, “The veteran Joe Start has been longing to get back to Brooklyn ever since the Providence team was broken up. He went to Washington reluctantly, and, though he has done his best while there, his heart was not in his work. … [Washington] released [him], and no club outside of Brooklyn has him.”65

After this final lackluster spell with the Nats, Start’s lifetime major-league batting average dipped below .300, to .299. For the final nine seasons of his career, he was the oldest player on any major-league roster. In this era it was not uncommon for veterans whose abilities had declined to sign on with minor-league teams to extend their professional careers, whether because they loved playing the game, they needed the money, or both. Start considered this undignified. According to Murnane’s 1895 interview, “Mr. Start believes a player should go out of the business after becoming a [Major] League player rather than play a farewell engagement with some weak minor league.”66

Over his career Start amassed 1,417 hits, 852 runs, and 544 RBIs in NA and NL play. Besides his .299 batting average, he logged a .322 on-base percentage and a .368 slugging percentage. These totals, of course, do not include his first 12 pre-league years. In addition, since Start’s lifetime totals were achieved in much shorter seasons than today’s major-league schedules, they tend to underrepresent his long-term value. He was a regular, everyday player, but Start did not appear in 100 games in a single season until age 42, in 1885.67 It is estimated that about 54 percent of Start’s quantified career hits (those from 1871 onward) occurred after he turned 36.

Despite hitting only 15 lifetime home runs in 16 major-league seasons, Start was considered a power hitter in his day. However, as Ryczek points out, in those days “power did not translate into home runs. … Outfield fences were far away, and the ball was very dead.”68 “How that old boy could hit,” remembered 1883–85 Grays teammate Arthur Irwin. “He just pointed his bat at the pitcher, swung it back with the heaver’s motion and met the ball squarely on the nose.”69

Although fielding statistics are subject to various interpretations, Start’s indicate that he was one of his era’s finest first basemen (a recurring opinion in contemporary accounts).70 “In his 10 full NL seasons … he finished first or second in putouts six times,” wrote early baseball historian Frederick Ivor-Campbell. “Five times he was first or second among first basemen in fielding average, and five times in chances per game. His average of nearly 10.9 putouts per game in National League play … is higher than that of the recognized all-time leading first baseman, as is also his average of nearly 11.5 chances per game.”71 An 1865 Eagle game recap rated each Atlantics fielder, declaring that “Start was immense at 1st base — in fact, he was Joe Start, and that is perfection.”72

Henry Chadwick, in an 1888 where-are-they-now feature on players from the 1860s, wrote, “Joe Start has retired from the diamond and keeps a saloon in Hartford, Conn.”73 Apparently Chadwick — still living in New York — had missed an item in the Clipper over a year earlier that reported, “Start is in Boston looking for a place to go into business. He had been keeping a hotel near Hartford, Ct., but it was burnt down about a month ago.”74 Start’s wayfaring ended with a return to Providence, where he lived the rest of his life.

In January 1890, Providence was reported to be fielding a club in the second (and what turned out to be final) season of the minor-league American Association (AA).75 A brief news item urged the club to hire Start as manager. “The selection of such a man … would be a good thing … and would infuse confidence in its stability among a host of lovers of the game in that city,” the item claimed. Start “has a reputation for honesty, reliability and faithfulness second to that of no ball tosser in the country. He would accept the position of manager if it were offered to him.”76 As it turned out, Providence did not place a team in the AA. The city then attempted to field a team in the New England League and offered the managerial reins to Joe, but he declined.77 Start, a man with exceptional leadership potential, never served as manager for any club.

Start “married only after years of caring for his widowed mother.”78 Angeline Prentice (née Creed, born November 5, 1838, in Rhode Island),79 a widow he married in 1893,80 was four years Start’s senior. (Joe’s mom, who remained in Brooklyn, survived until 1911.81) The newspapers had covered Joe’s exploits in the sports columns; Angeline’s first husband’s achievements were generally chronicled in the crime blotter.82 Angeline’s second marriage should be rated an upgrade.

By the mid-1890s, Joe and Angeline were operating the Hillside Hotel near Pawtuxet.83 In 1896 the Eagle reported that Start lived in Providence, “where he now keeps a fine road house just outside city limits.”84 The Starts sold the Hillside in early 1905.85 Within a year, they took proprietorship of the Lakewood Inn, in Lakewood.86

Although long out of the game, Start retained a keen interest in the game. In a 1912 interview he spoke admiringly about the sport’s evolving strategies:

“It’s the inside work that has been one of the greatest factors in making the game faster and more scientific. We used to have certain signals, but team work did not play the important part in the [1880s] that it does today. We manufactured runs by banging that ball on the nose as hard as we could … and while that is the secret of the success of winning clubs nowadays, there have been developments in base stealing, the hit-and-run game, sacrifice work, etc., that make it far easier to turn out the scores at the present time.”87

In 1920 Prohibition descended on the nation. The following year scandal engulfed the Lakewood Inn. The Warwick Welfare Federation, a citizen watchdog group, conducted a “green and amateur detective” investigation to gather evidence of illegal and immoral activities at four local hostelries.88 What they discovered at the Lakewood made headlines. Public officials were shocked — shocked! — to learn of the illicit sale and serving of liquor, and rooms being rented for prostitution.89 After the Police Commission conducted its own investigation, the licenses of the four establishments were revoked.90

Yet the reputation of “Old Reliable” remained unsullied. Shortly after 1914, Joe and Angeline had retired and sold the inn to William H. Connors, who ran it with his wife, Lydia.91 In 1919 the business was acquired by local entrepreneur John F. Ramsay, who was implicated in the debauchery.92

It appears the only scandal associated with Start is his absence from the Hall of Fame.

Angeline died on February 24, 1927, age 88. Joe died a month later, on March 27, at age 84, of heart disease.93 They are buried in Riverside Cemetery, in Pawtucket.94

Three years to the date after Angeline’s death, the former Lakewood Inn was destroyed in a fire.95

Acknowledgments

Thanks to William Ryczek, Eric Miklich, Tom Gilbert, Lisa Hirschfield, and Mary Anne Quinn of the Warwick (Rhode Island) Public Library Reference Department.

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Len Levin and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Several documents were obtained from the Joseph Start file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York.

Notes

1 William J. Ryczek, “My Favorite Nineteenth Century Player: Joe Start” (Society for American Baseball Research Nineteenth Century Committee, Summer 2018 newsletter): 1-3. Eric Miklich (via email, 2021): “The fair bound catch, retiring a batter, was part of the September 23, 1845 rules. It was removed from the rules after the 1864 season. The foul bound catch, retiring a batter, was also part of the September 23, 1845 rules. It was used throughout the Amateur Era, in the professional National Association (1871-1875), and in the National League until the end of the 1878 season. The NL re-instituted the rule for the 1880 season but removed it for good after 1882. When the American Association began operation in 1882, they allowed the foul batted ball bound rule until June 7, 1885.”

2 Peter Morris, A Game of Inches: The Story Behind the Innovations that Shaped Baseball (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2010, revised edition), 148.

3 William Rankin, The Sporting News, March 3, 1910 (quoted in Morris, A Game of Inches, 148).

4 “Atlantic vs. Mutual: A Glorious Game of Nine Innings,” Brooklyn Eagle, August 18, 1868: 2.

5 Frederick Ivor-Campbell, “Joe Start (Old Reliable)” (biographical sketch), Nineteenth Century Stars (Society for American Baseball Research, 1989), 117.

6 “Benefit of Joe Start,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 12, 1864: 2.

7 “The Professional Season,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 22, 1873: 2.

8 “Joe Start, First-Baseman,” New York Clipper, June 28, 1879: 109.

9 “Base Ball: Notes of the Day,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 6, 1882: 2.

10 Mark D. Rucker, “Start, Joseph ‘Joe,’ ‘Old Reliable,’” David L. Porter, ed., The Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball (Q–Z), (Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000), 1466.

11 Craig B. Waff and William J. Ryczek, “Atlantic Base Ball Club,” Base Ball Founders: The Clubs, Players, and Cities of the Northeast That Established the Game” (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2013), 135.

12 Baseball-Reference.com, Joe Start career stats. Start apparently played third base in his early years with the Atlantics. In Morris, A Game of Inches (140), Henry Chadwick in the New York Clipper (September 12, 1863) is quoted as arguing for Start to be switched from third to first: “Start was placed at third base, a position any player of the nine can fill better, because he is a left-handed player, and for that reason just the man for the opposite base.”

13 “Base Ball: Sketches of Noted Players — No. 5,” New York Clipper, April 24, 1869: 21.

14 Waff and Ryczek, 135. The first position players to employ gloves were catchers and first basemen in the 1870s; their use spread around the diamond during the mid-1880s. Many early players resisted, seeing gloves as unmanly. Others found them an encumbrance. As late as the 1890s, there were major-league fielders (e.g., Jerry Denny and Bid McPhee) who declined to wear gloves.

15 “The Famous Atlantics: Some Ball History Recalled by a Photograph,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 15, 1896: 22. Chapman was a teammate of Start on both the Enterprise and Atlantics.

16 Harold C. Burr, “At the Parade Grounds Rich in Color of Game,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 2, 1930: 28.

17 Ryczek. He is referring to players who graduated from amateur to pro. Lip Pike, who was born three years after Start, allegedly began playing at age 13 (1858), and played his last major-league game a year after Start retired. However, Pike was effectively washed up as a player by 1878 and made only token appearances in 1881 and 1887.

18 Letter from Norris G. Abbott Jr., vice president and assistant treasurer, Manufacturers Mutual Fire Insurance Co., to baseball historian Lee Allen, January 15, 1952 (National Baseball Hall of Fame Joe Start file).

19 Per US and New York State census records, the siblings, in order of birth over a 23-year span were Michael Jr., Rachel, Ephraim, Joseph, Hannah Ann, Sarah, Henrietta, George Washington, Percilla, Charles, Clarise, and James. There were spelling variants in some records (e.g., Ephrum, Persilia), but the above spellings recur most frequently. George died at 15; James lived less than 10 years, and Clarise died at age 2. Michael Sr.’s occupation was reported in various Brooklyn city directories from 1851 to 1858 as “fish vender” [sic], “fish,” “marketman,” and “pedler” [sic]. He died before James was born.

20 Rucker, 1466. I have not located any information about a school by this name. Rucker (via email, 2021) assumed the school was named after the intersecting streets. A Brooklyn street map from 1850 depicts a lone, unidentified building at the corner of Bedford and Madison, one block south of Monroe.

21 Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times, October 15, 1859 (page unknown), box score listing Start as Enterprise first baseman.

22 Henry Chadwick, Brooklyn Eagle, March 19, 1896: 2. In a letter to the Eagle over three decades after the facts, Chadwick wrote: “The death of [Atlantics players] John Oliver, Mat O’Brien and Archie McMahon weakened the old team considerably, and they recruited from the young Enterprise club, beginning with Charley [sic] Smith in 1860, who strengthened the old team’s weak point at third base, and Joe Oliver was substituted for McMahon at center field. The Philadelphia Athletics came to Brooklyn for the first time in 1862, and the Atlantics, through Mike Henry’s efforts, induced their pitcher, Tom Pratt, to join the Atlantics. Then they got Joe Start, Fred Crane and Jack Chapman from the Enterprise.”

23 Craig B. Waff, “The Silver Ball Game: Atlantics of Brooklyn vs. Eckfords,” in Bill Felber, ed., Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the Nineteenth Century, (Phoenix: SABR, 2013), 39.

24 Thomas W. Gilbert, How Baseball Happened (Boston: David R. Godine Publisher, 2020), 211. By 1860, James Creighton had “transformed the pitcher into the most important defensive position.” Other pitchers began to follow Creighton’s example.

25 Miklich, “Joe Start, 1842-1927,” 19cBaseball.com, 2016. Miklich (via email, 2021): “The Atlantics completed the 1864 season with a record of 20-0-1 and the 1865 season with a record of 18-0. Marshall Wright’s book on the pre-professional era, The National Association of Base Ball Players, 1857-1870, lists the season-ending records for hundreds of teams from 1845-1870. Although never to be considered the Bible, Torah or Koran (depending on one’s religious preference), the book serves as a starting point. The Beadle’s Guide for 1866 makes a reference to the ’65 Atlantics on page 59; however, it is incorrect in their seasonal wins tabulation. Beadle’s lists 19 games but only 17 wins, which of course pertains to NABBP-registered clubs. Wright’s compilation only indicates one match with the Gotham club and forgoes the NABBP match requirement. The 18-0 record for that season is the accepted Atlantic record for 1865.”

26 Tim Murnane, “Joe Start’s Ideas: Interesting Chat on Base Ball in the Early Days,” Sporting Life, November 16, 1895: 4.

27 Gilbert, 260.

28 Gilbert, 196.

29 “Benefit of Joe Start,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 12, 1864: 2. Joe also had brothers. None were named Edward. Item: “A Vagrant Brother of Joe Start,” Brooklyn Eagle, November 24, 1889: 3: “Edward Start was taken to the Jefferson Market Police Court in New York yesterday and sentenced to the Island for six months for vagrancy. The man pretends to be lame and carries crutches. He claims to be a brother of Joe Start, the base ball player.” (Note use of “pretends” and “claims.”)

30 Kings County, New York, Schedule 3 — Persons who Died during the Year ending 1st June 1860, in 2nd District 7th Ward Brooklyn. Cause of death was listed as “Intermitting fever.”

31 Marshall Wright, The National Association of Base Ball Players, 1857-1870 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2000).

32 Preston D. Orem, Baseball 1845–1881: From the Newspaper Accounts (self-published, 1961), 107.

33 Greg Rhodes, “The Atlantic Storm: Cincinnati Reds vs. Atlantics of Brooklyn,” Inventing Baseball, 72.

34 Murnane. In this interview, Start divulged a little-known secret: “We wanted to stop playing when the score was five each, but Harry Wright wouldn’t have it. You see, the Atlantics were playing on the co-operative plan, and another game meant $300 or $400 for each man.” Murnane confessed: “This was the first time I ever knew why the Brooklyn men left the field after the ninth inning, and I was present at the game.”

35 Gilbert, 347.

36 Orem, 107. Henry Chadwick wrote that a fan interfered with the batted ball, but McVey subsequently denied this.

37 The Rashomon of a single at-bat on June 14, 1870: (a) Orem,108: “It was a liner too hot for Charlie] Gould to handle cleanly, but he knocked it down; then made a bad muff in attempting to pick the ball up. Ferguson, already on third, then ran home for the deciding run.” (b) John Thorn and William Ryczek, in a 2019 simulated “radio” play-by-play of the game: “Hall hits a groundball to the right side, Sweasy … drops it — he drops it! Ferguson’s coming around third base, he’s going to try to score. Sweasy’s throw to the plate — it’s gonna be close! It’s a wild throw! It gets by catcher Doug] Allison! Zettlein’s going around to second base, Ferguson scores, it’s 8–7, the Atlantics have gone in the lead.” (c) SABR’s historical game chronicle (which includes the above “radio” simulation): “George Hall, the Atlantics’ center fielder, bounced a ball to George Wright, a sure double play, but George’s throw sailed by Sweasy, and Ferguson, running hard from second, scored the winning run.” (d) Brooklyn Eagle, June 15, 1870: 2: “Hall batted Zettlein out at second, and was nearly put out at second [sic] himself, but Sweasy dropped the ball passed in by George Wright, and Fergy got home.” Ryczek (via email, 2021): “I looked at several accounts and went with the versions which appeared most consistently. But one of the dangers of that is that the consistent accounts may have come from the same erroneous source.” If anyone reading this attended the game, please contact the author. We welcome an eyewitness account of the circumstances. Photos or film footage would be helpful.

38 Gilbert, 348.

39 Ivor-Campbell.

40 Gilbert, 349.

41 “The Chicago Attack on Ferguson,” Brooklyn Eagle, January 19, 1871: 4. “The Chicago, Athletic and Mutual Clubs, since the close of last season, have made strenuous exertions to procure the valuable services of Robert Ferguson, of the Atlantic Club, not only because he was a remarkably fine player, but especially because they knew him to be an upright and honest professional ball player, the very best reputation that class of ball players can possess. Ferguson wanted Joe Start and Charley [sic] Smith to go with him where he went, but the Athletics only wanted Ferguson, and so Rob did not go there, The Chicago and Mutual Clubs wanted all three, but Joe Start did not want to leave home, and Charley would not go outside of New York either. Chicago, however, was red hot for Fergy and Start, and so they offered them carte blanche. As neither cared much about going West this season, terms were named which were thought would not be accepted, but they were, and the two were offered $4,500 to become White Stocking players. Ferguson, however, knowing the uncertainty of base ball salaries in general and of Chicago arrangements in particular[,] wisely required that the salary should be secured to him to be paid at the close of the season. As there was some delay in acquiescing in this arrangement, and as the Mutuals’ offer was more to the taste of both players, knowing as they did that their pay would be sure from the Mutuals, and moreover that they would not have to leave home; they finally closed with the Mutuals, and became members of that club.”

42 The team leader in RBIs? The pitcher, Rynie Wolters. Baseball-reference.com.

43 “Base Ball Notes,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 20, 1873: 3.

44 “Baseball Faster Than in Old Days: Joe Start, First Baseman of Old Grays, Disagrees with Anson,” Providence Journal, March 23, 1912: 4.

45 Joe Start career stats at Baseball-Reference.com.

46 “Joe Start, First-Baseman,” New York Clipper, June 28, 1879: 109.

47 George Wright managed the Providence Grays for only one season, after which he moved back to Boston to tend to his sporting-goods business. He remains the only figure in history to win the pennant in the single season in which he managed. He made token game appearances for Boston in 1880 and 1881, then returned to Providence in 1882 to play under the management of his brother Harry, during which year George was a teammate of Start. George appeared in more than half of the season’s games, after which he retired from the field.

48 “Joe Start has been selected captain of the Providence team.” Sporting Life, January 16, 1884: 3.

49 New York Clipper, June 28, 1879: 109. Broken fingers were an occupational hazard, particularly for catchers and first basemen, before the advent of gloves. In 1884 the Chicago Tribune (as quoted by Edward Achorn; see Note 56 below) reported that Start, in trying to catch an errant throw, “got a finger knocked out.”

50 John R. Husman, “June 21, 1879: The Cameo of William Edward White,” SABR.org, reprinted from Inventing Baseball, 116–118.

51 Morris, 507.

52 Rick Harris, Joe Start biographical sketch, Rhode Island Baseball: The Early Years (Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2008), 83.

53 Harris.

54 “Providence Whips Brooklyn — Splendid Play by the Visiting Team — the Veteran Joe Start Gets a Reception,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 20, 1884: 12.

55 It took Start 20 years to become “Old” Joe. Radbourn, 12 years his junior, accomplished the same feat in less than four years. Start outlived “Old Hoss” by 42 birthdays.

56 Edward Achorn, Fifty-Nine in ’84: Old Hoss Radbourn, Barehanded Baseball & the Greatest Season a Pitcher Ever Had (New York: HarperCollins, 2010). Achorn describes Start as “a balding, clean-shaven man with a ruddy complexion and bracing blue eyes” (75). There are two 1884 team photos in the book; in both, Start clearly has a mustache. The book also notes that during the 1884 season, Start “missed a fair number of games because of the recurring agonies of malaria” (163).

57 Achorn, 163.

58 “Base Ball Notes,” Brooklyn Eagle, August 17, 1892: 2.

59 Ryczek.

60 “Joe Start, First-Baseman,” New York Clipper, June 28, 1879: 109.

61 Norman L. Macht, “From Hartford to Washington,” in Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 49. The team Start played for in his final major-league season, Washington, acquired a 23-year-old rookie catcher named Connie Mack, who was embarking on a 64-year-career in the major leagues. Rick Harris in Rhode Island Baseball writes that “during his last year in professional baseball, Joe was a teammate to a scrappy young upstart catcher. The rookie’s name? The ‘Gentleman’ of all baseball gentlemen, Connie Mack.” But their days with the team did not overlap. Mack joined Washington late in the season and made his major league debut on September 11, 1886, two months after Start had left the team.

62 “Sporting Information,” The National Republican (Washington), July 13, 1886: 1. “Yesterday the veteran Joe Start was released at his own request.”

63 Harris, 81.

64 “Base Ball,” Providence Journal, July 18, 1886: 7.

65 “Sports and Pastimes: Base Ball,” Brooklyn Eagle, July 17, 1886: 2.

66 Murnane.

67 Ryczek.

68 Ryczek.

69 “On Road with Grays,” Providence Journal, August 3, 1914: 6.

70 Ivor-Campbell.

71 Ivor-Campbell.

72 “The Day’s Play,” Brooklyn Eagle, November 7, 1865: 2.

73 Henry Chadwick, “Old Battles on the Baseball Field,” Outing magazine, May 1888: 120.

74 “Baseball: Notes from Everywhere,” New York Clipper, January 15, 1887: 698.

75 “Base Ball Notes,” Brooklyn Eagle, February 12, 1890: 5.

76 “A Chance for a Famous Veteran,” unidentified newspaper, January 15, 1890, in Joe Start file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

77 “Base Ball: Providence Will Join the New England League,” Providence Journal, January 19, 1890: 3. As it turned out, the New England League was inactive that year (and the previous). When it resumed in 1891, Providence did not place a team.

78 Waff and Ryczek: 135. An 1880 profile of Start in Beadle’s Dime Base-Ball Player said that his unimpeachable integrity as a player “gives him the means[,] in these hard times, of living comfortably, besides enabling him to support a widowed mother to whom he has ever been a dutiful son.”

79 Spelled “Prentiss” in a few contemporary news items, but Prentice more commonly found. Angeline Creed Start at Find-a-Grave (online database); Joe Start at Find-a-Grave. Note: Find-A-Grave, which is a crowd-sourced website, incorrectly lists Manhattan as Start’s birthplace. Start’s gravestone and death certificate indicate 1845 as his birth year, an error commonly repeated. Subsequent research has proven that Start was born in 1842, and this author has no idea where the three-year disparity originated. Start began playing for the Enterprise, a very competitive club, in 1859 when he was 16; it defies logic that he would want the club to assume he was 13.

80 New Jersey Marriages, 1678-1985, database, FamilySearch.org (familysearch.org/ark:/ 61903/1:1:FZLH-C36), Angeline Creed in marriage entry for Joseph Start, April 25, 1893, in Jersey City, New Jersey. At least one substantive biographical profile indicated, without source, that Joe and Angeline were married in 1871. In fact, in 1871 Angeline was married — to another man, hotel owner William L. Prentice. A 1900 US census record erroneously indicates the Starts married in 1885; the 1910 census stated they had been husband and wife for 17 years.

81 Hannah A. Start grave marker, Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York, at Findagrave.com.

82 Angeline’s first husband was apparently a badass. A search of the Providence Journal archives uncovers a pattern of court appearances over a 20-year period (1851–1870) for such infractions as illegal sale of liquor, frequenting a “bawdy house,” dogfighting, assault and battery, resisting arrest, and “breaking the windows and otherwise defacing a house” owned by a woman. Prentice forever ceased mischief-making on April 17, 1873; he was 49.

83 Various Providence Journal entries 1895 to 1904, e.g., Start granted a liquor license for the Hillside Hotel (May 1898); “the Hillside Hotel, near Pawtuxet” (April 1900); “Mrs. Start … conducts the Hillside Hotel” (December 1900); “Start keeps the Hillside Hotel in Warwick” (March 1904), etc.

84 “The Famous Atlantics: Some Ball History Recalled by a Photograph,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 15, 1896: 22.

85 Achorn, 290: “In April 1905, when [former Grays manager Frank Bancroft] was in Jacksonville, Florida, [he] ran into his team’s old captain Joe Start, who had just sold his hotel at Oakland Beach, near Providence, for $16,000, ensuring him a pleasant retirement.” That November, the Providence Journal (November 29, 1905: 7) reported that Nelson T. Viall was granted a liquor license for the Hillside Hotel.

86 A year after Viall obtained his liquor license for the Hillside, Start was granted one for the Lakewood Inn. Providence Sunday Journal, December 2, 1906: 13.

87 “Baseball Faster Than in Old Days,” Providence Journal, March 23, 1912: 4.

88 “Warwick Resorts’ Closing Demanded: Welfare Federation Claims Law Violation Evidence Against Roadhouses,” Providence Journal, November 2, 1921: 4.

89 “Affidavits Accuse Warwick Resorts: Immoral Conditions at Roadhouses Alleged by Residents of Town,” Providence Sunday Journal, October 30, 1921: 3. A chambermaid was overheard in the corridor “complaining because she had so many beds to make.” One amateur sleuth attested: “We ordered Scotch, which the man soon brought in on a tray. … [A]fter the man had gone out and closed the door, the whiskey was tasted and pronounced whiskey.”

90 “Warwick Resorts Licenses Revoked: Police Commission Declares Results of Investigation Justifying Closing Order,” Providence Journal, November 5, 1921: 11.

91 “Warwick: Townspeople Planning Welcome for Returning Soldiers,” Providence Journal, December 1, 1918: 11. “Mrs. Lydia E. Connors of Lakewood made application for a victualling license at the Lakewood Inn.”

92 “Four Road Houses May Lose Licenses / Warwick Police Board Issues Summons for Proprietors to Appear Nov. 4 / Midnight Visits Are Made,” Providence Journal, October 23, 1921: 5. After selling the Lakewood Inn, William Connors opened The Tavern, in Silver Hook. His establishment was one of the four whose licenses were revoked.

93 Death certificate, City of Providence, March 27, 1927.

94 Letter from Norris G. Abbott Jr.

95 “Four Fires Take Heavy Property Toll in State; Lakewood Inn Destroyed,” Providence Journal, February 25, 1929: 1.

Full Name

Joseph Start

Born

October 14, 1842 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

March 27, 1927 at Providence, RI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.