June 17, 1880: Perfection revisited by John Ward

Two perfect games within a week defies all odds.1 But that is exactly what happened when John Montgomery Ward pitched professional baseball’s second such game just five days after his antagonist, Lee Richmond, had thrown the first just 40 miles away.2 Ward’s game came on June 17, 1880, and was not duplicated until Cy Young did it for Boston in an American League game in 1904. The next three were also pitched by American Leaguers (including Don Larsen’s perfect game in the 1956 World Series). No National Leaguer matched it until Jim Bunning turned the trick in 1964.

Providence was destined to finish second in the 1880 National League race. The Grays played at a fine .619 clip, but finished 15 games behind Chicago, which had a sizzling .798 winning percentage. Buffalo, the victim of Ward’s perfect effort, finished seventh, ahead of only Cincinnati and playing less than .300 baseball. The teams may have been a bit mismatched that day, but the pitchers were not. Ward and Buffalo’s Pud Galvin were both destined for the Hall of Fame, the only such players on the field. Galvin was young, at 23, and already a proven winner, but just coming into his own as an established star. Ward, even younger at 20, had won 47 games for Providence in 1879 and was destined to notch 39 wins that season. Galvin was a good pitcher on a bad team while Ward was a good pitcher on a good team.

Providence was destined to finish second in the 1880 National League race. The Grays played at a fine .619 clip, but finished 15 games behind Chicago, which had a sizzling .798 winning percentage. Buffalo, the victim of Ward’s perfect effort, finished seventh, ahead of only Cincinnati and playing less than .300 baseball. The teams may have been a bit mismatched that day, but the pitchers were not. Ward and Buffalo’s Pud Galvin were both destined for the Hall of Fame, the only such players on the field. Galvin was young, at 23, and already a proven winner, but just coming into his own as an established star. Ward, even younger at 20, had won 47 games for Providence in 1879 and was destined to notch 39 wins that season. Galvin was a good pitcher on a bad team while Ward was a good pitcher on a good team.

The starting time for the Thursday contest, played at Providence’s Messer Street Park, was moved to 11 a.m. to avoid conflicting with boat races scheduled in Providence that afternoon. The ploy was successful, as a fine weekday crowd attended the game. The New York Clipper summarized Ward’s effort:

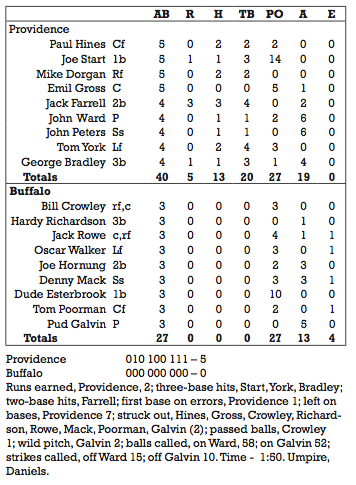

Ward pitched so effectively that not one safe hit was made off him while the entire field backed him up with perfect play. The result of this united work was that not one of the Buffalos reached first base in the entire nine innings, thus equaling the extraordinary Worcester-Cleveland contest on June 12.3

Of note is the usage of the descriptors “perfect play” and “united work.”4 Though the term “perfect game” had not yet been coined, the observer and writer recognized that the then rare errorless play and teamwork made the unblemished game possible. A Providence newspaper commented on fine defensive play in support of Ward: “Paul Hines playing in his position [center field] was remarkably fine, catching balls that looked good for two-base hits. John Peters [shortstop] made some wonderful stops.”5 The paper also commented on the hazard of being an unprotected catcher in 1880. “Jack Rowe and Bill Crowley changed positions in the middle of the fourth inning, on account of Rowe splitting his finger in trying to catch a foul tip.”6 Rowe’s treatment for his injury was to be sent to right field where he was, ostensibly, to heal. Providence prevailed, 5–0 (of course), and the game story was top and center on the front page of the Providence Daily Journal the next day:

…(E)ighteen hundred admirers of the national sport, who pronounced the fielding and batting exhibition of the champions excellent in every respect, [the Grays were the reigning National League pennant winners] as not one of the players of the visiting club were able to secure a safe hit off of Ward’s delivery, and not even allowing in the whole nine innings a man to reach the first bag without being put out.7

Certainly such a game cannot be pitched on demand but perhaps Ward’s effort was especially intense as he had an opportunity to equal his rival’s performance of five days earlier. Ward and Lee Richmond knew each other well. Richmond had pitched for Brown University, located in Providence. He and his Brown team faced the Providence professionals numerous times in exhibition games. Richmond never beat Ward as an amateur, but the tables were turned when Richmond pitched for money. He beat Ward when he made his major-league debut in September of 1879 and twice more that fall while pitching for Worcester. The following spring, with Richmond again an amateur pitching for Brown, Ward prevailed in two meetings. But then, after Richmond turned professional for a final time, he beat Ward and Providence in four of six meetings before their perfect efforts.

Certainly such a game cannot be pitched on demand but perhaps Ward’s effort was especially intense as he had an opportunity to equal his rival’s performance of five days earlier. Ward and Lee Richmond knew each other well. Richmond had pitched for Brown University, located in Providence. He and his Brown team faced the Providence professionals numerous times in exhibition games. Richmond never beat Ward as an amateur, but the tables were turned when Richmond pitched for money. He beat Ward when he made his major-league debut in September of 1879 and twice more that fall while pitching for Worcester. The following spring, with Richmond again an amateur pitching for Brown, Ward prevailed in two meetings. But then, after Richmond turned professional for a final time, he beat Ward and Providence in four of six meetings before their perfect efforts.

In his book Perfect!, Ronald Mayer wrote that “there was little love lost between these two rival pitchers. … Ward had a habit of hitting Richmond. Of course Richmond would retaliate whenever given the opportunity. And the bitter grudge lasted throughout their baseball careers.”8 It is at least an oddity that these two frequent opponents would both accomplish, within days of each other, a pitching feat not even thought of previously.

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Notes

1 According to baseball-reference.com, 201,156 regular-season major-league games have been played from 1871 through 2011. Using those numbers and the 19 perfect games pitched through 2011, a perfect game would occur on the average of once every 7.24 years or 10,587 games.

2 As stated by baseball-reference.com/bullpen/John_Ward: “While later baseball histories call him Monte frequently, he was not known by that name when he played. This appears to be an error on the part of historians.”

3 New York Clipper, June 28, 1880, p. 109.

4 New York Clipper, June 28, 1880, p. 109.

5 New York Clipper, June 28, 1880, p. 109.

6 New York Clipper, June 28, 1880, p. 109.

7 Ronald A. Mayer, Perfect! (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1991), p. 23.

8 Mayer, Perfect!, 23.

Additional Stats

Providence Grays 5

Buffalo Bisons 0

Messer Street Park

Providence, RI

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.