Toots Shor

Every great city has its own great bar.

Every great city has its own great bar.

Elizabethan London had the Mermaid Tavern. Paris has its Deux Magots. In New York City in the 1950s, there was no shortage of options, but for sports fans there was only one choice: Toots Shor’s.

Initially located at 51 East 51st Street, across the street from Radio City Music Hall and just a couple blocks from Madison Square Garden, the bar was the nexus of the New York sporting world — which in the 1950s meant it was the center of the sports universe.

Toots Shor’s has been called the first and possibly the greatest sports bar. It wasn’t a place where you could watch a game, or even listen to it, but it became known as “the country’s unofficial sports headquarters” by no less an authority than the New Yorker.1 On a given night, a Who’s Who of the sporting world could be found there, as well as the writers who covered them — and even some writers who didn’t. Earl Wilson stopped in twice a day, gathering material for his syndicated gossip column. Supposedly, Yogi Berra was introduced to Ernest Hemingway there. Berra, whose literary tastes ran toward comic books, asked, “What paper you with, Ernie?”2 (Toots Shor’s was also supposedly the place about which Berra said, “Nobody goes there anymore. It’s too crowded.”)

The patrons of the saloon — Shor refused to call it anything else — were not limited to the sports crowd. While visiting, you could see customers as varied as gangster Frank Costello, his lawyer Edward Bennett Williams, Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren, and actors like Jackie Gleason and Pat O’Brien. Frank Sinatra was a regular — and later sang about the place.3 Scenes from Sweet Smell of Success were filmed there. LeRoy Neiman immortalized the man and his bar in a painting. A generation later, Don DeLillo included Toots as a character in his novel Underworld. A decade beyond that, in the first season of Mad Men, Don and Betty Draper met Roger and Mona Sterling at Shor’s. It was a sign to Don that his ascent was at hand.

At the center of it all was its namesake, a hearty Falstaffian character who had risen from an urchin on the streets of South Philadelphia to — well, maybe not entirely polite society, but as close to it as he wanted. Rumors circulated that Shor was the basis for Harry Brock, the wealthy but unrefined heavy in Garson Kanin’s play and subsequent movie Born Yesterday. (Paul Douglas, who originated the role on Broadway, was a regular at Shor’s, as was Kanin before moving uptown.)4

Toots’s bar, much like the man himself, had its own unwritten code. Wives, while not barred, were not particularly welcome. Even less welcome were married men with women who weren’t their wives. (“I never ran a dame joint,” he said.5) Coats and ties were required; the lone exception was Bill Veeck. Off-color jokes were frowned upon.

Toots even had his own language. His friends were bums, or stewbums or crumb bums. The people he didn’t like? Well, they were pieces of raisin cake. Toots was a tough guy — before owning his own saloon, he worked the door at various mobbed-up speakeasies — but his most common exclamation was “Jiminy crickets!” And if you were a friend down on your heels, Toots would be more than happy to “give you the pencil,” meaning you could sign for what you needed and pay him back when you were flush. He had no problem extending the courtesy to many people; after all, it’s how he operated too. “He has the sure contempt for money that only a guy who’s been flat broke a half-dozen times and has always bounded back into the blue chips can ever have,” said Jerry D. Lewis, a radio and television writer, in a 1950 New Yorker profile.6

And above all, he was a passionate sports fan. As a boy in Philadelphia, he shined his sister’s shoes so she would take him to watch the Athletics at Shibe Park. He was an inveterate gambler — and a lousy one. “He was a knowledgeable sports fan, but he tended to wager with his heart,” wrote Frank Graham Jr.7 Shor lost $10,000 when Notre Dame rallied to beat Ohio State in 1935 (he’d never forget that day; it was his first wedding anniversary). He dropped another bundle a decade later betting on his friend, boxer Billy Conn, who’d actually lived with Shor and his family in the days leading up to his second bout with Joe Louis.

Athletes of any sport were always welcome at Toots Shor’s, but his first love remained baseball. He had box seats for both the Yankees and the Giants (his favorite team). Alexander Fleming, the discoverer of penicillin, took a customary back table. Toots was conversing with him when in walked the Giants’ Mel Ott, who’d hit his 500th home run earlier that day. “Excuse me, Alex,” Toots said. “but I have to go up front. Somebody important just arrived.”8

Toots cultivated a reputation of “professional illiteracy,” as he called it. Once, when he was talking to Shirley Povich about his column, the Washington Post writer said, “Who read it to you?” Toots sat in silence as everyone worried a line had been crossed: “You hurt his feelings!” “No he didn’t,” Toots said. “I’m trying to think who did read it to me!”9 As a favor to his friend, producer Michael Todd, he went to see his production of Hamlet, starring Sir John Gielgud and Maurice Evans. At intermission he said, “I bet I’m the only bum in the joint that’s going back just to see how it comes out.”10 But he’d studied at the Drexel Institute and briefly at the Wharton School before decamping to New York, where he achieved fame and fortune in the only career he’d ever wanted.

“If God told me I could have anything and do anything I wanted in life,” Red Smith recalled Shor saying, “I would say I wanted to be a saloonkeeper. Because where else could I make the friends I’ve got?”11

***

Bernard Shor was born May 6, 1903. His father, Abraham Schorr, was of Austrian descent. By the time he came to America in the 1880s, the family surname had become Shor, and he went to Philadelphia to learn how to make shirts. He met Fanny Kaufman and they married in 1895. They had two daughters before the birth of their son, who was nicknamed Tootsie because of his mop of curly blond hair. The nickname was later shortened to Toots.

The Jewish family settled in a largely Catholic neighborhood in South Philadelphia, where young Toots would find himself in fights after being on the receiving end of anti-Semitism, even if he was indifferent to his own faith (he took the money he was supposed to use to pay the rabbi for his bar mitzvah and blew it in a crap game). But Toots could be found regularly at the Church of the Annunciation — it had pool tables.

On August 29, 1918, Fanny Shor was on the front stoop of their home on 15th Street with her daughter Bertha and a neighbor. There had been a fire down the street, and an ambulance, speeding to the scene, hit a car and careened into the Shor house. Fanny was decapitated. Her husband never recovered from his grief, killing himself within five years. After his mother’s death, Shor started to cut school more. After his father’s suicide, Shor went to work, first at the Eclipse Shirt Company, where he worked his way up from the stockroom to sales covering his old haunts in South Philadelphia, and then to BVD. His sales territory included most of eastern Pennsylvania.12 Occasionally, though, his job took him to New York. The city fascinated him enough that he quit his job and moved there. Originally, he thought he’d work for Warner Brothers, but the man who was supposed to hire him had been fired.

Shor found employment as a bouncer and greeter at the Five O’Clock Club, a speakeasy owned by titans of the New York City underworld, Owney Madden and “Big Frenchy” De Mange. Shor would regale his sisters with tales of the celebrities that came in.13 He also met a Ziegfeld chorus girl named Marian Volk. Physically, they could not have been more different. Shor was over six feet tall and tipped the scales around 250 pounds. (When a British newspaper referred to him as 17 stone — 238 pounds — Shor said indignantly, “What kind of crack is that? It sounds like they keep track of how many times I got loaded!”)14 Marian, who was called Baby by everyone but her husband — he called her Husky — was five feet tall and weighed less than 100 pounds. They married on November 2, 1934, and remained married until his death. By all accounts, he was a devoted husband. They had three daughters (Bari, Kerry, and Tracey) and a son (Rory).

Shor then became manager of Billy LaHiff’s Tavern, a former speakeasy that was also frequented by writers and athletes, and lived above it with his wife. But he was ready to strike out on his own. On September 15, 1939, Shor signed a 21-year lease for his own bar and restaurant. It was a day he’d always remember, and not just because of its significance in his life. It was the day “Two Ton” Tony Galento beat Lou Nova at Municipal (later John F. Kennedy) Stadium in Philadelphia. After signing the lease, Shor then went to his friend, jazz pianist Eddy Duchin, and asked him for a blank check. Duchin signed it, but “I didn’t sleep for a week,” he said later. Ultimately, Shor came back to him with the check. All he had done was show vendors that Eddy Duchin was behind him, and they gave him whatever he wanted on credit.15

The restaurant cost $141,000 to complete, and opened on April 30, 1940. On his way in with his wife and columnist Jimmy Cannon, Shor reached into his pocket and pulled out a quarter, a dime and a nickel — at that point all the cash he had in the world. He threw it into the street, saying, “I might as well walk in flat-pocket.”16

Not long after Shor opened his saloon, the United States became involved in World War II. He was more than willing to accept the midnight curfew established in New York City, noting that “Any bum that can’t get drunk by midnight ain’t trying.”17 But he had a little harder time with food rationing. In 1943, Toots was found by the Office of Price Administration to have been overdrawn by 103,000 points for his meat rations, meaning he’d served more than 11 tons of meat more than he was allowed to. He said it was a clerical error, and noted he was one of the few restaurants in the city that wasn’t buying off the black market. It took three months to balance the books, using a menu laden with fish and chicken — a difficult order for a restaurant that had the standard fare of steaks and other beef dishes. But his friends were more than willing to support him. After all, the place wasn’t known for its cuisine.18

A three-part New Yorker profile said some of the restaurant’s nicknames included Chez Bicarb and the Heavenly Hashienda.19 Author James Michener, a regular at Shor’s, told Toots he had one chapter cut from his short story collection, Rascals in Paradise. It would have been called “Toots Shor: Horsemeat and Hamburger.”20 Shor’s second place had a dimmer switch installed, turning down the lights at 4 p.m. Cannon was in the bar one afternoon when the lights went down and said, “Thank God! They executed the chef!”21

In 1948, as his popularity was reaching its peak, Shor was offered 10 points in the Riviera Hotel in Las Vegas just for the use of his name. He turned it down, recalling wistfully decades later — when he really needed the money — that he’d be a multimillionaire. But money never mattered much to him. “I don’t want to be a millionaire,” he said; “just live like one.”22 Besides, he couldn’t leave his adopted hometown. “Everything outside of New York is Bridgeport,” he said.23

Because the bar became a hangout for the sports press of the day, it became the site of multiple news conferences. Army football coach Red Blaik would hold court there before games at Yankee Stadium. Major League Baseball Commissioner Ford Frick would regularly hold events there (his office was nearby, in Rockefeller Center), as would various other writers associations. Details for the sale of the Yankees from the estate of Jacob Ruppert were hammered out at Toots Shor’s. In the fall of 1948, reporters got a scoop on who the next Yankees manager would be when they spotted Casey Stengel there,24 They tried to get scoops on other deals, leading front-office figures to scrawl names on tablecloths as a practical joke.25 Shor’s was the launching pad for one of the most famous trades never to happen: when Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey and Yankees owner Dan Topping agreed to swap Joe DiMaggio for Ted Williams. Both decided to sleep on the deal — and no doubt sleep off the night at the saloon — but the trade couldn’t withstand the cold light of day (allegedly, Yawkey wanted the Yankees to throw in Yogi Berra).26

Shor was unabashed in his hero worship of DiMaggio, considering him one of the 10 greatest living men in the world.27 DiMaggio repaid that admiration in kind for many years. Someone once spotted DiMag running through midtown. “I just had lunch at 21 and I’m hurrying to Toots to tell him I did before somebody else does,” DiMaggio said.28 But their relationship turned frosty, and the reason depends on whom you ask. In Summer of ’49, David Halberstam said it was because Shor called Marilyn Monroe a whore in DiMaggio’s presence. Other sources also say Toots insulted Monroe. Bob Considine, a regular at the bar and author of a Shor biography, said the falling out was because DiMaggio didn’t show up at a charity dinner in Maryland.29 At least one account says DiMaggio froze Shor out after he appeared to be getting too chummy with Mickey Mantle, DiMaggio’s successor in center field for the Yankees.30

Shor was unabashed in his hero worship of DiMaggio, considering him one of the 10 greatest living men in the world.27 DiMaggio repaid that admiration in kind for many years. Someone once spotted DiMag running through midtown. “I just had lunch at 21 and I’m hurrying to Toots to tell him I did before somebody else does,” DiMaggio said.28 But their relationship turned frosty, and the reason depends on whom you ask. In Summer of ’49, David Halberstam said it was because Shor called Marilyn Monroe a whore in DiMaggio’s presence. Other sources also say Toots insulted Monroe. Bob Considine, a regular at the bar and author of a Shor biography, said the falling out was because DiMaggio didn’t show up at a charity dinner in Maryland.29 At least one account says DiMaggio froze Shor out after he appeared to be getting too chummy with Mickey Mantle, DiMaggio’s successor in center field for the Yankees.30

Shor even got his turn at baseball managing, turning out a team of all-stars to play against a team organized by the 21 Club at the Polo Grounds. Shor’s team included Joe DiMaggio and Carl Hubbell, as well as jockey Eddie Arcaro, tennis player Don Budge, golfer Jimmy Demaret, and boxers Rocky Marciano, Rocky Graziano, and Joe Louis. After beating the 21 team, Toots’s all-stars played at Yankee Stadium in an exhibition before a Yankees game. Shor bunted off the pitcher, actress Jinx Falkenburg, and catcher Bill Dickey threw the ball into right field. The throw from Tommy Henrich was high, and Shor took third. He could go no farther — literally. He wasn’t used to that much running.

In 1959, Shor sold his lease for $1.5 million, prompting him to tell his wife, “Honey, put your arms around a millionaire.”31 The building would be redeveloped by William Zeckendorf, who’d previously made bids to buy into the Dodgers — helping Branch Rickey drive up his sale price — and the St. Louis Browns. Shor himself swung the wrecking ball, painted to look like a baseball, and smiled for pictures afterward.32 A new restaurant was planned, but leaving 51 West 51 turned out to be the end of an era.

On October 7, 1960, Shor and a company of his friends — including Jackie Gleason, Chief Justice Earl Warren, and baseball luminaries like Berra, Mantle, and Commissioner Frick — gathered in a tent for the ceremonial groundbreaking on Shor’s new restaurant.33 (Ironically, Zeckendorf’s plans for the former site of Shor’s restaurant had died months before.34) The new saloon was funded generously by a loan from the Teamsters pension fund. It opened under the same name as the old place on December 27, 1961. The new location, 33 West 52nd Street, held some historical significance for Shor: It was formerly Billy LaHiff’s, where he’d worked 30 years earlier.35 Once again, Shor’s wife and Jimmy Cannon arrived together. She was wearing mink this time, and they’d come by limousine. Photographers lined the street as she reached into her purse, pulled out 40 cents and threw it into the street. “For luck,” she said.36

By design, the restaurant was the same. But times had changed, and the magic was gone. The Dodgers and Giants had both decamped for the West Coast, and after losing the 1964 World Series to the Cardinals, the Yankees’ fortunes started to decline precipitously. In the 1950s, afternoon baseball made it possible for players to shower and change and reporters to write, then head to Toots Shor’s for the evening. Now games were being played more regularly at night.

The Polo Grounds, where Shor’s all-star team had beaten the 21 Club’s squad, served as home briefly to the expansion New York Mets and the AFL’s New York Jets, but both those teams soon left for Shea Stadium in Queens. Population was also fleeing for the outer boroughs and beyond. Madison Square Garden moved downtown to the site of the former Penn Station. No longer could people walk a couple blocks after a fight or a game to Toots’s place.

Even the bar itself became archaic. A newspaper strike in the early 1960s claimed four of the city’s papers, and sports writing was home to a new breed, derisively named “chipmunks” by Shor’s old friend Jimmy Cannon.37 Shor said they were the type “who leave a sporting event and go home and have a milkshake.”38 It was also no longer the draw for athletes it once was. Joe Namath said he had no interest in going there, “because the owner spills drinks on you.”39 (Shor was equally unimpressed with Namath: “Bobby Layne drank more booze and had more broads in one season than Namath will have in his career.”)40 It wasn’t just Toots. Bars that weren’t as welcoming to women were fading as a bustling scene of new “singles bars” started to pop up — on the East Side, with places like Maxwell’s Plum and the original TGI Friday’s.41

There were flashes of the way things used to be. Shor got to see Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, which he said “was the thrill of a lifetime.” Afterward, Shor said Ford’s pitching added two years to Mantle’s career. Mantle said nights at Shor’s took five years off it.42 In 1988, Mantle opened his own sports bar in New York — and he said he wanted it to be like Toots Shor’s.43

After the contract was signed for what turned out to be the first of three Muhammad Ali-Joe Frazier fights, the news conference was held at Shor’s restaurant.44 But the next two fights were not only not in New York, they weren’t even in the United States — another ill omen for Shor’s fortunes.

In 1971, the 52nd Street restaurant was padlocked shut. Shor owed $49,000 in back income taxes. He had always played fast and loose with the IRS. He declared his season tickets as a promotional expense, and was challenged on that claim. A tax investigator said it was a leisure activity. Shor retorted, “Did you ever have to watch the St. Louis Browns three days in a row?” The deduction stood.45 When the restaurant was closed, Shor said, “I’ll be open again in three or four weeks.”46

It took a year and a half and another new location, on East 54th Street. That, too, failed, and by the end, he sold his name to Riese Brothers restaurants, and could be found at some of them, telling tales about the good old days, like Sitting Bull in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows, Earl Warren’s grandson wrote later.47 Health problems started to catch up with Shor, too. In 1970, in Washington for a dinner honoring his friend and biographer Considine, Shor slipped on a throw rug and broke his hip.48 He had arthritis and battled cancer throughout the 1970s.

In 1975, a friend tried to do Shor a favor. Paul Screvane, head of the state’s Off-Track Betting Corporation, hired Shor as a consultant two days a week. Red Smith covered the initial news conference, noting that it got Toots back in action. Screvane, a former New York City Commissioner of Sanitation and City Council president, said he planned to take advantage of Toots’s considerable connections, and that Shor’s role might include some lobbying.49

The move was roundly excoriated. “Who was the New York Off-Track Betting Corp. genius who suggested putting Bernard (Toots) Shor on the payroll at $150 a day plus expenses, to do a job for which Shor admits he has no particular qualifications?” wrote Ed Comerford of Newsday.50

Shor found himself best known at the funerals he attended, which were becoming more common for an aging man who counted many, many friends. He was seen at the funeral of former Mets owner (and Giants shareholder) Joan Whitney Payson,51 and Casey Stengel’s shortly thereafter. (Stengel’s Mets career had come to an end after he fell and broke his hip following a boisterous postgame party at Shor’s.) Five years before, he’d made an embarrassing appearance at Vince Lombardi’s funeral. Shor, who could carry a load with the best of them, was sloppy drunk and made a scene at the NFL owners’ lunch afterward.52 Cleveland Plain Dealer sports editor Hal Lebovitz told a similar story about Shor, “obviously in his cups,” knocking Ewing Kauffman’s wife out of the way in a receiving line for Richard Nixon and almost starting a fight with her husband.53 He was far better behaved at gangster Frank Costello’s funeral, telling a New York Times reporter, “He was very fine and decent, a good family man.”54

Shor died on January 23, 1977. Hundreds turned out for his funeral at Temple Emanu-El, including sports luminaries Ralph Kiner, Eddie Arcaro, Gabe Paul, and Mel Allen. “Toots Shor was a great man and a good man,” said Msgr. William McCormack, a friend of Shor’s and later New York’s auxiliary bishop. “He was a magnet around which flowed many of the special streams of New York’s greatness,” said Rabbi Ronald Sobel. Shor was interred in Ferncliff Cemetery.55

That December at the site of the original Toots Shors, 51 West 51st Street, a crowd gathered to dedicate a plaque, reminding onlookers for generations afterward what was once there. Among the people there to pay tribute were Berra and Monte Irvin — and the commissioners from all four major sports leagues.56

“There never was a gathering place like it, and there never will be again,” Red Smith said.57

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht. It was fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Considine, Bob, Toots, New York: Meredith Press, 1969.

Halberstam, David, Summer of ’49, New York: William Morrow & Co., 1989.

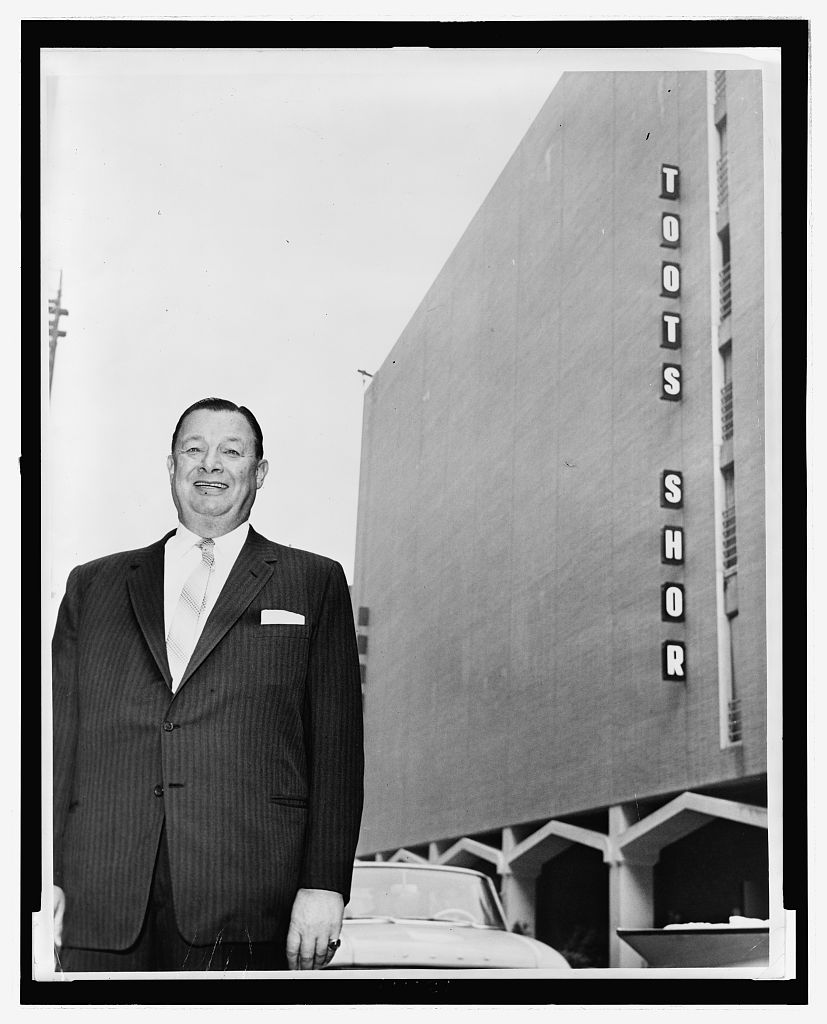

Photo credits: New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, Library of Congress.

Notes

1 John Bainbridge, “Toots’ World,” The New Yorker, November 11, 1950: 54

2 Halberstam, 124.

3 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qskSIrqSySc

4 Bainbridge, 52.

5 Joe Flaherty, “Toots Among the Ruins,” Esquire, October 1974. http://www.thestacksreader.com/toots-among-the-ruins/

6John Bainbridge, “Toots’ World,” The New Yorker, November 25, 1950: 42.

7 Graham Jr., Frank, A Farewell to Heroes, New York: Viking Press, 1981.

8 Bob Addie, “Toots Shor’s Life of Big Names, One-Lines Is Slowing Down,” The Washington Post, January 23, 1977. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/sports/1977/01/23/toots-shors-life-of-big-names-one-liners-is-slowing-down/6d30ee87-84bf-4ef6-9412-91c136583315/

9 Considine, 66/

10 Bainbridge, November 25, 1950.

11 Red Smith, “Toots’ Guys Were Waiting For Him,” Sports of the Times, The New York Times, January 26, 1977.

12 Bainbridge, November 11, 1950: 62.

13 Bainbridge, November 11, 1950: 64.

14 Considine, 139/

15 Considine, 50/

16 Considine, 52.

17 Bainbridge, November 11, 1950: 54.

18 Considine, 69-70/

19 Bainbridge, November 11, 1950: 56.

20 Considine, 168-69.

21 Considine, 192/

22 Dave Anderson, “Derek meets ‘the Legend,’” The New York Times, January 26, 1975.

23 Shirley Povich, “The Apple of New York’s Eye,” The Washington Post, November 11, 1996 https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/sports/1996/11/01/the-apple-of-new-yorks-eye/f9ed4353-9b2f-4523-b7e4-7cdb10a80c90/

24 Dan Daniel, “Shor Lists Big Yarns He Leaked,” The Sporting News, June 24, 1959: 5.

25 J.G. Taylor Spink, “Shor’s Red Carpet Out For Series,” The Sporting News, October 1, 1958: 17.

26 Dave Anderson, “Those Sundry Yankee-Red Sox Deals,” Sports of the Times, The New York Times, December 18, 1980.

27 Bainbridge, November 11, 1950: 54.

28 Considine, 172.

29 Considine, 174.

30 Bill Scheft, “The Glory of Their Times,” The New York Times, June 5, 2011.

31 Considine, 88/

32 Jeff Byles, “The Romance of the Wrecking Ball,” The New York Times, January 22, 2006.

33 Gay Talese, “Toos Shor Opens 52d Street Tent,” The New York Times, October 8, 1960.

34 Glenn Fowler, “Zeckendorf Drops 52d Street Hotel Site,” The New York Times, July 21, 1960.

35 Gay Talese, “Toots Shor Opens the New ‘Joint,’ and the old Bunch Settles Inn,” The New York Times, December 28, 1961.

36 Considine. 151.

37 Bryan Curtis, “No Chattering in the Press Box,” Grantland. https://grantland.com/features/larry-merchant-leonard-shecter-chipmunks-sportswriting-clan/

38 Flaherty.

39 Halberstam, 275.

40 Flaherty.

41 Aaron Goldfarb, “Revisiting TGI Fridays and the Revolutionary ‘Fern’ Bars of Late-1960s New York” https://www.insidehook.com/article/food-and-drink/upper-east-side-fern-singles-bar-history-1960s-tgi-fridays

42 Flaherty.

43 Steven Erlanger, “In Search of Toots Shor: Mantle’s Back,” The New York Times, February 5, 1988.

44 Arthur Daley, “It’s Only Money,” Sports of the Times, The New York Times, December 30, 1970.

45 Bainbridge, November 11, 1950: 56.

46 Alfred E. Clark, “Tax Lien Forced Toots Shor’s to Close,” The New York Times, April 3, 1971.

47 Jeff Warren, “Notes from St. Helena: Toots had class,” The Napa Valley Register, September 13, 2007. https://napavalleyregister.com/community/star/news/opinion/columnists/jeff-warren/notes-from-st-helena-toots-had-class/article_9fe18004-1953-55ec-8e5b-e365e09f2b40.html

48 Bob Addie, “Sports Patron Toots Shor Dies,” The Washington Post, January 25, 1977. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/sports/1977/01/25/sports-patron-toots-shor-dies/f9813a15-7925-4694-b95c-eb1ed779a3c0/

49 Red Smith, “New Boy in the Bookie Joint,” The New York Times, February 12, 1975. https://www.nytimes.com/1975/02/12/archives/red-smith-new-boy-in-the-bookie-joint.html

50 As quoted in Irving Rudd, The Sporting Life, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990.

51 Paul L. Montgomery, “Diverse Friends of Joan Payson Fill Church for Last Good-bys,” The New York Times, October 8, 1975.

52 Evan Thomas, The Man To See, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992: 249.

53 Hal Lebovitz, “Ask Hal,” The Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 27, 1977.

54 Emanuel Perlmutter, “Costello buried after brief rites,” The New York Times, February 22, 1973.

55 Joseph Durso, “500 Attend Service for Toots Shor,” The New York Times, January 27, 1977.

56 Red Smith, “Tribute To a Saloonkeeper,” Sports of the Times, The New York Times, December 1, 1977.

57 Red Smith, “World’s Greatest Saloonkeeper,” Sports of the Times, The New York Times, December 24, 1976.

Full Name

Bernard Shor

Born

May 6, 1903 at Philadelphia, PA (US)

Died

January 23, 1977 at New York, NY (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.