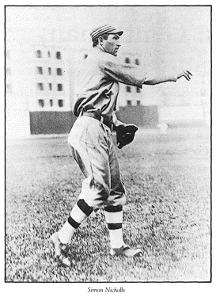

Simon Nicholls: Gentleman, Farmer, Ballplayer

This article was written by Campbell Gibson

This article was published in 1989 Baseball Research Journal

“Was Simon Nicholls a typical turn-of-the-century player? Maybe not, but he certainly represented an overlooked contributor to the era: the well-mannered college grad. If you take into account the proportion of the total population that went to college back in those days I think it’s pretty clear that we had more than our share of college men in baseball. And it’s also pretty clear that the usual picture you get of the old-time ballplayer as an illiterate rowdy contains an awful lot more fiction than it does fact.” — Harry Hooper, in The Glory of Their Times

Turn-of-the-Century ballplayers were constantly fighting a reputation for fast living and coarse behavior. As Hooper states, this stereotype was overdrawn. Among the ranks were many college men-the best-known perhaps being that illustrious Bucknell product, Christy Mathewson-and many gentlemen.

Turn-of-the-Century ballplayers were constantly fighting a reputation for fast living and coarse behavior. As Hooper states, this stereotype was overdrawn. Among the ranks were many college men-the best-known perhaps being that illustrious Bucknell product, Christy Mathewson-and many gentlemen.

One of the best combinations of degrees and decorum was a little-known infielder named Simon Burdette Nicholls. The first graduate of Maryland Agricultural College (later called the University of Maryland) to play in the majors, Nicholls was a farmer and family man. In fact, his concern for personal and community life may have cut short his big-league career.

Simon was born on July 17, 1882 near Germantown, Maryland, the son of George Nicholls, a farmer, and Courtney Burdette Nicholls, who died when Simon was five years old.

During his four years at college, Nicholls was the team’s shortstop and star player, but despite his reputation on the ballfield it was not certain that he would play professionally, at least partly because of parental objection. When the 1903 class historian of the Maryland Agricultural College prepared a prophecy for the year 1935, it envisioned Simon as a gentleman farmer with ample time to take part in local politics.

In September, 1903 Nicholls was recruited by the Detroit Tigers, who were short of infielders and in the area to play the Washington Senators. He made his major league debut on September 18 in a doubleheader. In the first game, Simon had two hits and fielded well, but in the second game, after being picked off first base, he lost his composure and made three errors. The consensus of the Detroit and Washington papers was that he needed experience but had played quite well for a young man jumping from the amateur level to the major leagues.

In the following two years, Nicholls competed for several amateur and semi-professional teams, two of which won championships. In 1904, he played for the town of Ridgely on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. Ridgely had only about 800 residents, but the team recruited widely and won the Maryland “amateur” championship, although several of the team’s players were paid. The most notable attribute of the 1904 Ridgely team was that it included five future major leaguers: Sam Frock (P), Bill Kellogg (1B), Buck Herzog (2B), Frank Baker (3B), and Simon Nicholls (SS).

The following year Nicholls played for Piedmont, West Virginia, which finished first in the Cumberland Valley League. At Piedmont, Simon’s play impressed Charlie Babb, and shortly after Babb was signed to manage Memphis in the Southern Association in 1906, he signed Simon to play shortstop. Nicholls’ fine play in spring training drew attention, and John McGraw, manager of the New York Giants, offered to purchase him but was turned down.

The 1906 season was a very successful one for Nicholls and the Memphis team, which finished second, Simon played every inning of the club’s 142 league games. He hit 260, well above the league average of .230, and was a standout defensively. Near the end of the campaign, Connie Mack, manager of the Philadelphia Athletics, purchased Nicholls for $2,500, and Simon joined the A’s for the last few games of the major-league season.

The Athletics’ starting infield for 1907 was set with veterans Danny Murphy (2B), Jack Knight (3B), and Monte Cross (SS), so Nicholls was a utility infielder. In June, Murphy suffered a sprained ankle, and Nicholls was inserted in the infield. Mack then traded Knight (and $7,500) to Boston for third baseman Jimmy Collins. With Nicholls playing second base and Collins and Cross at their regular positions, the A’s won 15 of their next 20 games to move into pennant contention. Simon contributed to this spurt with a 20-game hitting streak during which he hit .413 and moved to the top of the American League batting race. His hitting dropped off, but when Murphy returned to the lineup in July, Mack moved Nicholls to shortstop in place of the aging Cross.

The American League pennant race in 1907 was one of the best in history, and in early September, only two games separated the top four teams. First Cleveland and then Chicago dropped back, and prior to the opening of a three-game series between Detroit and the Athletics in Philadelphia on Friday, September 27, the A’s trailed the Tigers by just one-half game.

In the first game, the Athletics left 12 men on base and lost 5 to 4. Saturday’s game was rained out, and because Sunday baseball was not then legal in Pennsylvania, a doubleheader was scheduled for Monday. As it turned out, only one game was played, and it was a classic, as described by baseball historian John Thorn in “Baseball’s 10 Greatest Games.”

Before a crowd of about 24,000 (including about 6,000 standing in the outfield), the Athletics built up a 7 to 1 lead; the Tigers, however, scored four runs in the seventh inning with the aid of errors by Rube Oldring and Nicholls. And with the A’s leading 8 to 6, Ty Cobb hit a dramatic two-run home run in the ninth inning to tie the game. After Detroit scored in the eleventh inning, Nicholls doubled and later scored to tie the game at 9 to 9. In the fourteenth inning, the A’s Harry Davis led off with what appeared to be a ground-rule double into the centerfield crowd. After a prolonged argument and melee on the field and disagreement between the two umpires, Davis was ruled out because of interference by a policeman with centerfielder Sam Crawford when he tried to catch Davis’s long drive. Murphy’s ensuing single, which would have scored Davis with the winning run, went for naught. After 17 innings, the game was called on account of darkness, and the A’s, who were hoping to win a doubleheader and regain first place, ended the day one and a half games behind Detroit.

The Athletics won five of their remaining seven games, but it was not enough. The Tigers, inspired by escaping Philadelphia without a loss, won their next five games to clinch the pennant.

While the last series with Detroit and his costly error in the second game must have dampened Nicholls’s feelings about the 1907 season, it was a successful one for both the Athletics, who had not been viewed as pennant contenders, and for Simon. He hit .302 in 126 games to finish fifth in the league behind Cobb, Crawford, George Stone, and Elmer Flick, and just ahead of the great Nap Lajoie. Simon had also been versatile in the field, playing shortstop, second base, and third base. If there had been Rookie of the Year awards in 1907, Nicholls would have been a prime candidate for American League honors.

Mack was optimistic about his club’s chances in 1908; however, the Athletics were out of the pennant race by July. The team’s hitting fell sharply, with Nicholls’ average plummeting to .216. Simon’s batting average was actually not so bad for a shortstop because the American League average was only .239, but his fielding fell off as well.

While Nicholls’s poor 1908 season raised some question about his future with the Athletics, it was all the more uncertain because of four young infielders whom Mack was grooming for stardom. By 1911, they would be known as the “$100,000 infield”: Stuffy McInnis (1B, though originally a shortstop), Eddie Collins (2B), Frank (Home Run) Baker (3B), and Jack Barry (SS).

Nicholls was designated as a utility infielder for the Athletics in 1909, but Baker suffered a spike wound in an exhibition game, and Simon played third base on opening day, April 12, in Philadelphia against the Boston Red Sox. The game marked the opening of Shibe Park-the first of the new wave of steel-and-concrete stadiums-which was packed with an unprecedented 35,000 fans. This historic game turned out to be one of the best of Simon’s career. In the first inning, he singled to register the first base hit in Shibe Park and then scored the first run. Altogether, Simon had a double, two singles, and a walk and scored four runs as the Athletics won 8 to 1.

For the season, Nicholls played in only 21 games and hit .211. Barry, the regular shortstop, hit only .215 and fielded poorly. Barry was only twenty-one years old, however, and Mack no doubt expected him to improve with age and experience.

In December, Mack traded Nicholls to Cleveland for outfielder Wilbur Goode. Simon reported to Cleveland’s spring training camp in 1910, but never showed the form expected of him, partly owing to family concerns. In October 1908, Simon had married eighteen-year old Marie Conneen of Philadelphia, and in the following September, their first child, a daughter, was born. Travel between Philadelphia and the Nicholls’s family farm in Maryland was relatively easy. Cleveland was several hundred miles northwest of the two focal points of their lives.

After appearing in just three games with Cleveland, Nicholls was sold farther west to Kansas City of the American Association in early May. He refused to report and returned home to Maryland.

The Baltimore Orioles (then in the Eastern League) got off to a poor start in 1910 because of a weak infield. Manager Jack Dunn purchased Nicholls from Kansas City, and with Simon at shortstop, the Baltimore Sun reported that the Oriole infield was 100 percent improved.

The Orioles finished in third place, and Simon hit .255, which was the highest among the league’s shortstops. While he was no longer in the major leagues, playing regularly and close to home must have made the 1910 season especially satisfying. Dunn developed a strong friendship with Simon as well as respect for his leadership on the field and named him the Orioles field captain for the 1911 season. In February, Simon and his family moved from the farm to a house on Cator Avenue in Baltimore.

On March 5, the Nicholls’ second child, a son, was born, but what should have been a joyous occasion was tempered by the diagnosis received the previous day that Simon had typhoid fever. His case did not appear to be severe, but after a few days he developed pelvic peritonitis. An operation provided the only chance for his recovery. After surgery, hemorrhaging developed and all hope for Simon’s recovery was lost. On the morning of March 12, George Nicholls saw his dying son for the last time, the dolorous scene being recounted in the Baltimore Sun:

About 11 o’clock Simon’s father arrived at his son’s bedside. Simon was breathing hard and was conscious.

“Hello, papa,” said Simon just above a whisper, as he feebly clasped the white-haired, stately old gentleman’s right hand between both of his.

Tears trickled down the furrowed cheeks of the father as he looked at his dying son, the pride of his heart.

The evening edition of the Baltimore News reported on the front page that the popular Oriole captain died about 1:45 that afternoon. Simon’s wife, weak from childbirth and the tragedy, had not been able to see her dying husband, and Simon never saw his newborn son.

After funeral services were held at the Nicholls home, Dunn accompanied the body to Philadelphia. Simon was buried in Holy Cross Cemetery in Yeadon, just west of Philadelphia. The inscription on the tombstone reads: “My beloved husband, Simon B. Nichols, died March 12, 1911.” Unfortunately, the much more common spelling of his surname accompanied him in perpetuity.

On April 11, the day before the opening of the American League seasons the Philadelphia Athletics, now world champions, came to Baltimore to play the Orioles on “Nicholls Day.” More than 5,000 fans turned out in tribute to the memory of the young Oriole captain, and $3,000 was raised for his widow.

Perhaps the finest tribute to Nicholls appeared the day after his death in the Baltimore News under the by-line of “Danny,” a sportswriter whose surname is unknown:

In the game on the field he was a fighter, but of the right sort. He was always out to win, and did everything in his power to do it, but never stepped beyond the bounds of what would be considered proper by a thoroughbred gentleman.

Though the sport on the diamond was a big thing in the life of Simon Nicholls, he was a home man, not the make-believe sort, and that, after all, topped everything else.

Nic thought well enough of Baltimore to become a citizen. He belonged to us, and we should feel it a duty to see that the widow and youngsters will realize to the end of their days that his death was not the earthly end of just a ball player, but a man respected and honored by everyone who had the pleasure to know him as a friend either off or on the field.