He May Be Fast, But Is He Quick?

This article was written by Jim Reisler

This article was published in Summer 2009 Baseball Research Journal

During the 2007 baseball season, Jim Reisler interviewed nine former major-league players about baserunning. Following are transcripts of his interviews with three of them—Tim Raines, one of the game’s leading basestealers; Tommy John, a pitcher; and Butch Wynegar, a catcher.

TIM RAINES

With 808 career stolen bases, Tim Raines is one of the top basestealers in the history of the game. A native of Sanford, Florida, Raines spent 23 big-league seasons compiling a lifetime batting average of .294 while play- ing for the Expos, White Sox, Yankees, and three other teams.

With 808 career stolen bases, Tim Raines is one of the top basestealers in the history of the game. A native of Sanford, Florida, Raines spent 23 big-league seasons compiling a lifetime batting average of .294 while play- ing for the Expos, White Sox, Yankees, and three other teams.

After appearing briefly for Montreal in 1979 and 1980, the switch-hitting Raines established himself as one of baseball’s premier leadoff men by batting .304, stealing a league-leading 71 bases, and scoring 61 runs in the 88 games of the strike-shortened 1981 season, after which he was named National League Rookie of the Year.

Raines then led the league for the next three years in a row in stolen bases, achieving his career high of 90 in 1983. A seven-time All-Star, he is the only player in major-league history to steal 70 or more bases in six straight seasons.

Raines’s .334 batting average in 1986 led the league. In 1990 he was traded to the White Sox, where he spent five years. He then signed with the Yankees, where he played three years and was a part of World Series championships in 1996 and 1998. Early in 1999 Raines signed as a free agent with Oakland, but halfway through the season he was diagnosed with lupus.

Raines recovered, however, and was back in the big leagues in 2001 with the Orioles, where he joined his son, Tim Raines Jr. With Tim Sr. in left field and Tim Jr. in center field, the the two of them became the second father-son combination, after the Griffeys, to play on the same team. After finishing his career with the Florida Marlins in 2002, Raines became a coach and a minor-league manager. When interviewed in 2007, he was coaching the Harrisburg Senators. He is currently manager of the Newark Bears.

I never really kept track of the number of stolen bases I had at any one time—at least not the way people today keep track. If I had, I’d have probably stolen a lot more bases—probably more than a thousand. For me, stealing bases meant helping the team win games; it wasn’t about stats.

I stole bases because that was the way our team won games. In Montreal we utilized speed, so I utilized mine. I wasn’t a home-run hitter; my game was getting on base and trying to make something happen. I don’t really remember any significant stolen bases— number 100 or number 300, for instance. The one exception is number 500, which came when I was with the Yankees and we were playing against the Expos in Montreal. Doing it where I’d spent a lot of years made it special.

In hindsight, what might have helped me steal more bases and get me into the Hall of Fame was stealing more when games were out of hand. Normally, when you’re up or down eight runs, the other team won’t hold you on base. But I didn’t run in those situations, because doing so would be seen as showing up the opponent. I was afraid the other team would retaliate by throwing at one of my teammates or me. Rickey Henderson would usually go in that situation, and so would Vince Coleman and a lot of guys, regardless of the score. They’ve since changed the rules; today, if the game is out of hand and they’re not holding you on, you can steal a base but not get credit for it. But I still wouldn’t run, even if it meant a thousand stolen bases would get me to the Hall; I didn’t play the game that way and wasn’t concerned with stats. I just played to win.

When I started in the big leagues, I used sheer speed to steal bases. Back then, the pitchers weren’t as concerned about baserunners as they are today. If you stole a base, they’d resolve to strike out the next two batters, so it didn’t really matter to them if you were on base or not: They didn’t have the slide step or quick release to the plate. Those things alone can reduce a pitcher’s time to the plate to 1.1 seconds, from 1.4 seconds or 1.5 seconds, making it a lot harder for the runner.

Nowadays, pitchers—even the power pitchers—go to instructional leagues, where they’re taught how to develop a slide step. And speed has even changed catching; today, teams hire catching instructors who go around and work with catchers on their timing. They try to get catchers to work on their throws to second—getting them to reach the bag more quickly, usually in 1.8 or 1.9 seconds. Doing that gives the team in the field more of a chance.

The changes have meant that speed isn’t so big a part of the game today. In my day, there were usually three or four guys who stole a lot of bases—myself, Rickey [Henderson], Vince [Coleman], Ozzie Smith, and Lonnie Smith. Vince, Ozzie, and Lonnie were part of those Cardinal teams; they ran all the time, and were pretty much the only team that relied, big-time, on the stolen base. Most teams had one or two guys with a chance to steal 50 or more bases a year.

At the same time, teams probably have more green-light guys today. If you demonstrate that you can steal bases, a lot of managers today will just let you run— though the minute you’re not successful, you’ll be shut down. When I got to the big leagues, Ron LeFlore had been with Montreal, so the team was certainly used to speed. Ron had the green light, and I was similar. So they took a chance with letting me run, and it worked out.

My method of stealing wasn’t to crouch low like Rickey, but to take more of a standing lead—an athletic position. It was my way, which made stealing bases more of a reaction move. I had to work on it; my thing was to maintain my flexibility and speed by running a lot and doing a lot of stretching. In the offseason I always played basketball to maintain my fitness. And I picked up knowledge about the opposing pitchers pretty fast; I learned, because I figured when I got older, I wasn’t going to have the same speed, so I could use that knowledge to my advantage. We’d go through every pitcher and his times to the plate, what kind of motion and pitches he’d tend to throw with men on base, and the catchers’ times. So when I got on base, I already knew what the pitcher was likely to do.

Take Pedro Martinez. Every time with a guy on base, he takes a big windup on the first pitch to the next batter and delivers it in 1.4 or 1.5 seconds. Then on every pitch after that, he speeds up and delivers the ball in 1.1 seconds or thereabouts. With Pedro, I knew his tendencies, so, if I got on base and he was on the mound, I knew to go on his first pitch.

When you’re taking about speed, Rickey was fast, but there were a lot of guys who were faster. What Rickey had was quickness; his first step was as quick as anyone’s. There’s a difference between reaction to what you see and how quick you react to it—and the best basestealers know that. The key is having instinct, which you can’t teach, no matter how much speed you have. Lou Brock had that instinct.

Also, to be a good basestealer, you need to have the mentality that “I’m going to get a bag every time I’m on base, I don’t care who’s catching and who’s pitching.” Even when you’re thrown out stealing, you have to keep that confidence. For the most part you’re stealing off the pitcher, but you have to let the catcher know that “it’s me and you.” Even if it’s usually the pitcher you’re victimizing, keep in mind that the catcher is probably going to call for fastballs, or three or four fastballs and then a pitchout, or a fastball up and away—a good pitch for throwing to second—to do what he can to catch you out.

Stealing bases is a cat-and-mouse game. A lot of times, a baserunner at first can look in and tell if it’s going to be a pitchout. I’m trying to get the signs, especially as the game goes on. It’s all part of that other dimension, that running, like an ability to hit home runs, brings to a team. The other team always knew when Raines came to town, “We’re going to have to keep him off the bases.” And they knew if they did that, they’d have a chance to win the game. But the other team also knew that unlike a home-run hitter, they couldn’t walk me, or even groove it down the middle, because I could hit, too.

Somebody who can steal disrupts everything. The middle infielders are moving around. The catcher is fidgety. The pitcher is all screwed up. And everybody else on the other team is saying, “Well, if he goes, I got to back the play up.” Everybody is moving. And not only does the team have to worry about the guy on base, but they still need to concentrate on the guy at the plate. Meantime, the guy at bat loves it because he’s looking for something they’re bound to groove right over the plate so the catcher has a good ball to throw. So the team at bat tries putting a batter behind the guy on base, someone who can take pitches and handle the bat. With a home-run hitter, all you do is move back to the wall, or hope your pitcher strikes him out. Stolen bases change the whole game.

I developed my speed from playing football. In high school [Seminole High School in Sanford, Florida] I played four sports—football, basketball, and baseball, and ran track. In the spring I played baseball, and on days when we didn’t have a game, I did track. I never really practiced track, but just went out and did the meets—running the 100, the relays and the 330-yard intermediate hurdles, and long jumping. The first time I ran the 100, I broke the school and conference record. And though I never really practiced the long jump, I set the school record, which lasted for a good 20 years, until it was broken by a guy who became an Olympic triple jumper.

Being a running back in football helped me develop quick feet. It’s a pretty basic exercise: When guys come after you, you just run faster. So to me, a guy trying to tackle me is a lot like stealing a base— you need quickness and a good first step. Playing basketball helped me maintain my quickness as well— and so did playing sports with my family, starting with my dad, who played baseball, and my brothers, who played football, basketball, and baseball.

All my brothers were older, which meant growing up, I always had to play with older guys if I wanted to play at all. So when I was five I was playing baseball— and catching—in a league against eight-year-olds, when I should have been playing tee-ball. I remember one time when a guy ran me over at the plate, and I cried. But I loved it; I was playing with my brothers in a league where I wasn’t supposed to be playing, but they let me play. At a young age, it helped me feel the competition against bigger and supposedly better kids. I learned to rise to the talent level, so by the time I got to competing against people my own age, it was like a man playing against boys.

Once I reached the major leagues, it was a lot like being a kid again and playing against my brothers. I told myself that I shouldn’t feel like a rookie, because I’d been competing against older, bigger athletes my whole life. That helped, because you have to have that confidence going into the big leagues; otherwise, you’re not going to be around long. You have to feel like you fit in. Montreal called me up briefly in 1979, and then again in 1980, when I went 1 for 20. But I always thought that I could compete against these guys; all I needed was a chance. So in ’80, I went down to Triple A, to Denver, and told myself that, when I go back up, I’m going to be ready. I won the Minor League Player of the Year Award and a batting title and set the league record for stolen bases.1 So then I said to myself, “Okay, now that I proved to the minor leagues that I’m beyond their level . . . I’m ready for the big leagues.”

In 1981 I went up for good, and it didn’t feel like such a big deal, because I was ready for the transition. The best thing to happen early on came in my first game of my first full season: I walked my first time up,2 stole second, and scored when the ball got away. That was the biggest thing for my confidence; I was able to do something that most guys just don’t do. People said, “Wow!” And I said to myself, “Okay, I’m here.”

In my day, Rickey and I were the two guys people would talk about when it came to stolen bases. But we could run and were both good hitters. People don’t always talk about Rickey’s ability at the plate—but he had 3,055 career hits, and has more career home runs leading off a game than anyone in history [81], and had power [297 lifetime home runs]. The ability to steal bases is what kept me in the major leagues early in my career, but, as my career extended, it was my ability at the plate that distinguished me, I think. I won the batting title in 1986, hit .300 or more eight times, and could hit home runs [170 homers, lifetime]. Yet people don’t look at it that way, in part because I played in Montreal (and out of the spotlight) for so long. They never put two and two—the ability to run and hit—together. Either you were a runner, a hitter, or a power hitter; Rickey and I were all three, and even as leadoff guys, we drove in runs.

At the same time, basestealers don’t really seek one another out. We don’t have to; Rickey had his way of doing things, I had mine, and Vince Coleman had his way. The only major difference between myself and them was the way I stood up or bent down when taking a lead or my first step. But I paid attention to what Rickey and the others were doing, so, when it comes to coaching and teaching, I can draw on what they did. I tell young players the way Rickey did it, Coleman did it, and I did it; that way, we can try ’em all and see which works best.

Though I played a lot of years in Montreal, what helped me get some exposure was playing in the All-Star Game (seven in all). My first couple of years, we had a bunch of guys make the All-Star team: Andre Dawson, Gary Carter, Steve Rogers, and myself, so people knew about us. In 1981 we won the NL East and lost to the Dodgers in the championship series, but I swear we had a better team than they did. We had some good teams and had a great minor-league system, but didn’t have those one or two players who could have put us over the hump. The Expos didn’t have the money, and a lot of people didn’t want to play in Montreal.

In rating ballplayers today, speed is part of the overall package, but reaction time is still more important, to my mind. You can have the fastest guy in the world, but if he doesn’t know how to read the pitcher, or if his reaction time is a step slow, he doesn’t do a team much good. When I was 30 I wasn’t as fast as I was at 22, but I had learned how to pick and choose my attempts. If there was a breaking-ball pitcher, even though he was a slide stepper, I’d pick a certain count and go. For pitchers I knew well, I’d try to anticipate when he might throw over. Having speed changes the dynamic of the game; with speed on the bases, you can expect catchers to call a lot of fastballs; they like throwing guys out and don’t want to be the guys who give up the stolen bases. And pitchers don’t want to get guys into scoring position.

On this team [the Harrisburg Senators], we have one green-light guy, and even he’s shut down by the manager occasionally. We also don’t know the pitchers in the minor leagues; sometimes, all we know about the opposing pitcher is that he’s a left-hander or a right-hander. We take it game by game; we time the opposing pitchers and work on timing. The difference in the big leagues is that they have stats on everything. Steve Boros, my first-base coach in Montreal, was the first guy who got me into stats. He’d give me and all the guys our times to first base and tell us the pitcher’s times to the plate. I learned that any pitcher who would deliver the ball at 1.3 seconds and above, I figured I had a chance. But most pitchers didn’t have the slide step back then, so I figured I had a chance to steal on pretty much anyone.

When I played, most of the power pitchers had big kicks, and they weren’t that concerned with trying to speed up their deliveries. They figured that by changing their mechanics, they would add several miles per hour on their fastballs. It’s not that they weren’t concerned; they’d throw over and try to pick you off, and you had catchers who called more fastballs in case you ran.

Today, you still have guys who go through the wind-up, but they take a peek at the runner at first; back then they weren’t really concerned. And for the team at bat, they seldom want to take a chance at a stolen base in front of their three, four, or five hitters. They want to give those guys a chance to drive runners home. Look at Boston, who haven’t had much speed since Johnny Damon went to the Yankees. They have Coco Crisp,3 who can run but is not a blazer, and is often shut down. That team is built on power.

Notes

- Raines stole 71 bases in 1981 and reached a career high of 90 in His record was broken in 1984 by Vince Coleman, who stole 101 bases that year with Louisville in the American Association.

- Several at-bats are combined in Raines’s memory of this game. In his first regular-season appearance at the plate, on April 9, 1982, he flew out to left. He walked on his fourth plate appearance.

- Crisp played for the Boston Red Sox through In November 2008 he was traded to the Kansas City Royals.

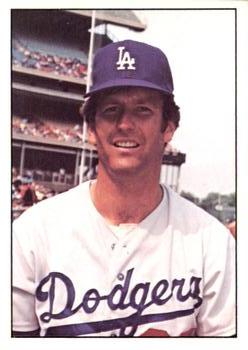

TOMMY JOHN

Tommy John is noted for his big-game mastery in 26 big-league seasons—and for undergoing the pioneering ligament-repair operation that would eventually become known as Tommy John surgery—an operation most thought would end his major-league career.

Tommy John is noted for his big-game mastery in 26 big-league seasons—and for undergoing the pioneering ligament-repair operation that would eventually become known as Tommy John surgery—an operation most thought would end his major-league career.

John, a left-hander, made his big-league debut in 1963 with the Cleveland Indians and earned a reputation as one of the American League’s premier control pitchers. Traded to Los Angeles in the winter of 1971, John in 1974 permanently damaged the ulnar collateral ligament in his pitching arm, prompting a revolutionary surgical operation. The surgery, performed by Dr. Frank Jobe in 1974, involved replacement of the ligament in the elbow of John’s pitching arm with a tendon from his right forearm. After a year’s recovery, John was back in the Dodgers’ rotation in 1976.

John went on to pitch until 1989 and earned 164 of his 288 victories after his surgery. In 1976, John received the Hutch Award for displaying honor, courage, and dedication to baseball both on and off the field. Following the 1981 season, he was named winner of the Lou Gehrig Memorial Award, which is given to the player who best exemplifies the character of Lou Gehrig. John had three seasons of 20 or more wins, he was selected to four All-Star Games, and he played in four World Series.

Tommy John had difficulty holding runners on base when he joined the National League in 1972, but Maury Wills coached him to speed up his motion, and he learned from watching tape of Jim Kaat’s quick release. Today, John serves as manager of the independent Bridgeport Bluefish. The once revolutionary and experimental operation that bears his name has now become standard, and many well-known pitchers, including Kerry Wood and John Smoltz, have benefited from Tommy John surgery.

The best basestealers? When I started out, one was Luis Aparicio. He was tough. If he played in this era, he may have 100 stolen bases. Back then, you would steal a base only when it was appropriate. Today, play- ers just steal at any time.

The first time I ever saw Luis was in 1959 when he was with the “Go-Go” White Sox. He was like a rocket. But for the most part, American League players just didn’t steal a lot of bases back then, nor did they into the late ’60s. After Luis, the White Sox didn’t have any basestealers, and neither did the Tigers or the Red Sox. Why? It was the way the game was played and the mentality back then. American League players would sit back and hit the long ball.

There were some exceptions. Rod Carew of the Twins was a great basestealer, and in 1969, he stole home seven times. He tried it on me once with Bob Allison at the plate, but I saw him start to break out of the corner of my eye, and just threw home in a quick motion. I got him, and the Twins claimed I had balked. But the umpire’s decision stood. I got him.

But when I went to the National League in 1972 with the Dodgers, the mentality about stolen bases was different. In the NL, the idea was to create runs. When I got there, Lou Brock and Joe Morgan were the premier basestealers. In my first year with the Dodgers, I played with Maury Wills, one of the best. Then the Dodgers brought up Davey Lopes from the minors, and he became one of the very best as well.

Joining the National League, I had the hardest time in holding runners on base. I had pitching coaches work with me, but they couldn’t get through to me, and my problem continued. But then at spring training at Vero Beach with the Dodgers a year or so later, Maury, who was coaching, took me out to one of the half-fields and we had a session. I went to the mound, and every time I’d go home, he would take off from first; I couldn’t go to first. I asked, Could he tell when I committed to the plate? Maury was “reading” me— picking up my gestures. He told me that he could steal off me any time he chose—and that the only way I could ever get anyone to hold at first was if I sped up my motion and went to home more quickly.

At the time, Jim Kaat was a member of the White Sox, and had developed a quick release with runners on base. So when the Dodgers were in Chicago to play the Cubs, I called the White Sox and asked them to set up a tape of Kaat pitching. They agreed, and when we were playing at Wrigley Field, the Dodgers gave me permission to go to Comiskey Park, where I watched a 30-minute tape of Kaat pitching. Based on what I saw, I started working on a motion like Kaat’s. It was quicker—and all of a sudden, I was getting to the plate fast enough so runners on base couldn’t steal off me. I got to the point where I was getting the ball to home in 1.1 seconds, which is phenomenally fast.

Most big-league catchers can get the ball to second base in about 1.9 seconds. So between my pitching and their throwing to second, it would take only three seconds. That was fast—and fast enough to catch runners. They couldn’t steal. My new motion got guys to stop stealing off me.

From that point, only certain guys were going to run on me. Contrary to the book Moneyball and the thinking of Billy Beane, stolen bases may not mean a lot over the long haul, but baserunners can use them to create havoc in a game. Baserunners make a team in the field do things they don’t want to do, all to keep them from running—starting with pitchers making a bad pitch home. If you’re a pitcher, you can’t put the focus on home and on a runner at first base. It has to be one or the other.

A good baserunner gets into a pitcher’s mind. If a pitcher gives 50–50—that is, he focuses on both home and on the runner in an equal amount—then he can’t make a quality pitch. Pitchers have to pay more attention to the batter than they do a runner. It’s got to be that way.

In my case, though, I’d had enough experience when I got to the National League that I “quick” pitched and didn’t worry about the baserunner. I would just come set and throw home—and even if a runner had a walking lead, he still couldn’t steal off me. I could get the ball to the plate faster than he could steal.

When I came up, prospects weren’t evaluated much on their speed. But today, you hear a lot about “five- tool players”—those who excel at hitting for average, hitting for power, baserunning and speed, throwing ability, and fielding abilities. Those tools are teachable, all but speed, which is an exception. Speed and a 95- mile-an-hour fastball are things you’re born with; you either have it or you don’t.

You can, however, teach good baserunning. Bernie Williams was fast, but not a good basestealer. He could go from second to home or first to third well, but he never developed any skill in stealing bases. On the other hand, Maury Wills wasn’t especially fast, but he was quick, and became the premier basestealer of his day. Later in my career, Don Baylor and Jose Canseco were both good basestealers—not people you thought of as exceptionally fast, but able to run the bases well and able to take advantage of a situation.

Good basestealers need to read the pitchers. They need to anticipate situations in which to run and know when to run. And they have to be able to do what Maury could do, which is to reach top speed after their first step. There were a bunch of guys who could probably beat Maury going first to third base, but in his prime, no one was better than Maury in getting from first to second.

Maury told me once that, contrary to the common thought, it was easier for him to steal on a left-handed pitcher than a right-hander. Left-handers face first base but give it away easier, he said. Maury could take a good lead and draw a throw two and three times in a row, and be able to read that pitcher and know exactly what he could do. Maury was a very savvy ballplayer.

If the count is 0–1, it’s generally a good time to run, because the pitcher is liable to follow with a breaking ball. If it’s a 1–0 or a 1–1 count, it probably isn’t a good time to run, because the opposing manager may think he can afford a pitchout. But if you’re going to steal with a hitter’s count of 2–0, 2–1, or 3–1, you’re taking a risk and kind of taking the bat out of the batter’s hands. In most situations, if the batter sees you running, he’s going to take the pitch. If you’re running later in the count, you had better make it.

Good baserunners can also steal signs by taking a good lead and peeking in at the catcher’s signs. Rickey Henderson could do that. On the other hand, Rickey couldn’t steal off Bob Boone if his life depended on it. The reason was that Boone had a particular thumb signal for the pitcher to “throw over” to first base. Boone would open his legs just a little as he was giving the sign and let Rickey see that he was telling the pitcher to throw over. But in reality, the sign was for the pitcher to throw a fastball, which he’d then do with Rickey crossed up and staying at first base.

For pitchouts, Boone had another sign—a series of signs, actually—in which he would pump his fingers four consecutive times. In Rickey’s case, it worked again—and kept him close to the bag.

A good baserunner adds a dimension to your offense. They get in the head of the pitcher. And they make the infielders play up and stay closer to the bag. Baserunners get the second basemen, for instance, to “cheat in,” as we call it, by keeping a step closer to the plate in case of a bunt. That means you can’t cover as much of an area if the hitter sends the ball by you. There’s a lot that goes into basestealing and baserunning. As a manager, I don’t think enough thought goes into it.

In the majors, players get to know the pitchers. But in the minor leagues, we don’t know many of the opposing pitchers—and so we give our players the green light. If they get a good jump, they can run. If they feel they can steal a base, they can run. That goes for about five of our players, who have the green light. In this league, we have a watch on the opposing pitchers. If they deliver to the plate in 1.4 or 1.5 seconds, which isn’t fast, we usually tell our baserunners that they can go. We don’t look for speed necessarily, but if they have it, well, that’s gravy.

To my mind, basestealing has very little to do with the ballgame, except in the last three innings. You can steal four, five, or six bases early in the game, and a home run gets you right back in the game. But if you’re down a run in the late innings and it’s a close game, stolen bases can mean a lot. You can steal second and get to third on a bunt, you can score on a sacrifice fly—and it’s a new game.

Today’s premier basestealer? Probably José Reyes of the Mets. There are some good baserunners out there, but basestealing has gotten more challenging with the smaller ballparks. When they get smaller, it’s not necessary to steal bases to score runs. You can wait for the fat pitch and it’s gone.

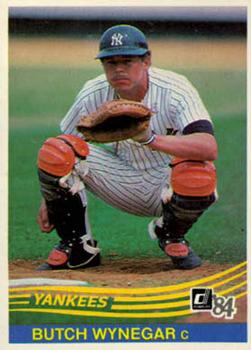

BUTCH WYNEGAR

Described on a Minnesota Twins blogsite as “Joe Mauer before there was a Joe Mauer,” Butch Wynegar was a switch-hitting highschool catcher from York, Pennsylvania, when he was selected by the Twins in the second round of the 1974 draft. After winning the Appalachian League batting title (.346) in his first pro season, Wynegar reached the major leagues in 1976 at the age of 20, and that season he became the youngest position player to play in the All-Star Game.

Described on a Minnesota Twins blogsite as “Joe Mauer before there was a Joe Mauer,” Butch Wynegar was a switch-hitting highschool catcher from York, Pennsylvania, when he was selected by the Twins in the second round of the 1974 draft. After winning the Appalachian League batting title (.346) in his first pro season, Wynegar reached the major leagues in 1976 at the age of 20, and that season he became the youngest position player to play in the All-Star Game.

An outstanding defensive catcher, Wynegar was named The Sporting News’s American League Rookie of the Year that season, after hitting .260 with 10 home runs and 69 RBIs. He would be an All-Star again in 1977 and would play 13 big-league seasons, mostly with the Twins, and later with the Yankees and Angels. In his best season, with the 1983 Yankees, Wynegar hit .296 and caught Dave Righetti’s no-hitter.

After his playing career ended, Wynegar was a minor-league manager and coach in the Baltimore Orioles’ and Texas Rangers’ farm systems before he joined the Milwaukee Brewers as batting coach in 2003. He now coaches the Scranton–Wilkes-Barre Yankees.

In my day, there were a bunch of guys who could steal bases. Mickey Rivers of the Yankees was one. And the Oakland A’s had a number of basestealers, guys like Rickey Henderson; Herb Washington, the designated runner; Billy North; and Miguel Diloné, who could fly. Kansas City had a bunch of great runners as well, like Willie Wilson, Frank White, and Amos Otis.

I’d say that 90 percent of stolen bases are swiped off the pitcher. Today, there are statistics—basically [there’s] a stat on the Internet for anything you want to find—for the combined time a pitcher throws to plate (1.3 seconds is typical) and a catcher then throws to second base (in, say, 2.0 seconds). That’s a total of 3.3 seconds from the time a pitcher releases the ball to the time a catcher gets it to second—which is too slow for a fast runner, who can usually get from first to second in about 3.1 seconds. Today you can keep track of all these things.

It’s almost funny to compare all these statistics to the lack of stats when I got to the big leagues in 1976. I had just turned 20, and though I knew how to catch, I still had a lot to learn, namely about basestealers. I remember being so wrapped up during my first season about when a guy was going to run that I had about 18 passed balls. Sure, we practiced our throws to second and to third, but I never knew what my times were until later in my career. I didn’t think about it; I just tried to be as quick and accurate as I could in my throws.

A team’s tendency to run is really up to the manager. Billy Martin was very aggressive, and he would run in any situation with anyone and at any time. When he was managing Oakland, Billy used an old play on me, shortly after I’d come up: With runners at first and third base and two strikes on the batter, the guy at first would take a secondary lead and trip and fall. So of course, I’d get the ball, cock my arm, and throw to first—with the guy at third coming to the plate the second I commit to first. He scores, and we retire the guy at first in a rundown. It was a preset play that required the runners to leave their bases at the right time and some pretty good acting on the part of the first-base runner, who had to fall down. If only I’d cocked my arm and stopped and looked at third, we’d have had the guy coming from third. But being a young catcher, I fell for it.

Gene Mauch was my first big-league manager, as well as my mentor and father figure when I was away from home. He was the one who taught me pretty much everything about the game—helping me refine what I learned as a kid from my dad. I remember Gene taking all the pitchers aside at spring training and telling them they simply had to cut down the time delivering the ball to the plate—from 1.5 or 1.6 seconds down to 1.2 or 1.3—all to give the catcher a chance to catch basestealers.

Gene recognized when a pitcher was slow and tried to deal with it. As a catcher, I got sick and tired, early in my career, with pitchers taking their time delivering the ball to the plate, and then having to make up for it. I began hurrying my throws and bouncing them in the dirt, or throwing the ball into center field because my footwork got out of whack. We were playing the A’s one day when Rickey Henderson stole second, and I looked at the scoreboard and saw “E-2,” and I said to myself: “F— this! Give me a chance to catch Rickey Henderson. All I want is a chance to throw in 1.9 seconds down to second and make an accurate throw.” That was the turning point in my career behind the plate; I vowed to myself to set myself and make a good throw, regardless of a runner’s jump. Because of that mentality, I became a better thrower, and the monkey was off my back.

Being 20 at the time and catching experienced and successful pitchers like Bert Blyleven and Davey Goltz, who were both about ten years old than me, I couldn’t very well go out to the mound and say, “Give me a pitch I can throw on, will you?” So I vowed to myself to make more accurate throws, and knew that Gene would deal with getting the pitchers to deliver the ball more quickly. I had to take care of myself and do my job as best I could.

As a catcher, dealing with baserunners was still a matter of not trying to be so quick. I tell our catchers here all the time that if you can throw to second in 1.9 seconds, stick with that speed and you’ll be okay. Don’t come out and try to be Ivan Rodriguez and throw the ball to second in 1.7 seconds. You’ll get air- balls if you try to throw too fast.

Gene taught me something else about how to be a better catcher: He told me to get to know the pitching staff. “Every one of them has a different personality,” Gene said. “I want you to know your staff inside and out—what they throw, when they want to throw it, what they eat for lunch, and what they eat for breakfast.” He wanted me to really know my pitchers, know their strengths, weaknesses, and tendencies, and how to talk to them. If nothing else, I had to become a psychologist; if I knew Jimmy Hughes had a big leg-kick, which made him slow to the plate, I had to find some way to get him to deliver the ball a little faster, so I’d have a chance to catch a baserunner. No wonder so many catchers become managers and coaches; we’re experts at dealing with so many different personalities. We’re dealing with the manager and in scouting meetings. Yup, we’re the psychologists of baseball.

Even when you get a good runner at first and he doesn’t want to go, the catcher doesn’t know that. That was my problem catching during my first couple of years in the big leagues: I always had one eye on the pitcher and my other eye down at first, if a good runner was on base. The pitcher gets concerned, too, and throws over to first a bunch of times. His rhythm is disrupted. The whole game changes.

There was a time when catchers didn’t have to hit, when the three basics were receiving, throwing, and blocking. If you could do those things at a high standard, then you had a good chance to make the big leagues. But today’s game has become so oriented to offense that catchers have to hit. The same thing goes for shortstops: In contrast to the old days, when a lot of them were Punch-and-Judy hitters who could field and had rocket arms, today’s shortstops are guys like Derek Jeter and Miguel Tejada, who can hit the ball out of the ballpark.

The focus on offense has made the stolen base a lot less prevalent than in my day. Those old Oakland and Kansas City teams oriented their whole teams around speed. The Royals had [Willie] Wilson, [Frank] White, [Amos] Otis, Al Cowens, and George Brett. Their whole lineup could run, and playing them was like a track meet. Oakland could [do that] too, and there were days when they just ran rampant and I was helpless, I had no chance in throwing their guys out.

Brett was a good example of a guy who wasn’t a speed demon, but knew how to run and steal bases. He was smart on the base paths, a guy who knew he couldn’t outrun the ball, so he had to be heads-up when running. You seldom see a basestealer get on first and then just run. The good ones are looking for a good count to run on, a breaking ball or a changeup. When we played the Red Sox at Fenway Park, my arm got out of shape, because they ran so often that it was almost not worth even trying to throw people out. It was just rat-a-tat, all the time. Between the designated hitter and the small ballpark, their attitude was just to bombard your opponent. Though I never played in the National League, I spent four years there as a coach in Milwaukee, and I’ve got to admit I like the NL style of play: There’s more running—though it doesn’t take much to outrun the American League— and there’s no DH. That means there’s more strategy, too: Do we pinch-hit for the pitcher? Do we bunt the runner over? Do we run in this pitch? There’s a lot of thinking going on.

The orientation on offense today isn’t because players are quicker. I’ll admit that they’re bigger and stronger. But from a catcher’s standpoint, the first thing scouts will tell you is they can’t find catchers these days. It was at the suggestion of a White Sox

scout that I became a catcher in my junior year of high school; he came up to me after a game and said, “Butch, have you ever thought about catching?” I was a third baseman and pitched a little at the time, but I had good hands, a good arm and switch-hit—though I lacked range at third. The scout’s thought was [that] a switch-hitting catcher with a good arm could reach the big leagues pretty quickly. Fortunately, I had a highschool coach who agreed, and so I became a catcher, which I’d played some in Little League. By the time I reached the big leagues, I had three years of catching under my belt.

Here at the Triple-A level, where we don’t always know much about the opposing pitcher, we’ll give a watch to the first-base coach who will time the pitcher’s delivery, and then talk about it with the runners. If the pitcher takes 1.5 seconds to the plate, our runners are usually free to go. Do it right, and someone who isn’t speedy can learn his way around the bases. John Wathan, who set the catcher’s record for most stolen bases in a season (36 for the 1982 Royals), was a good example; he had a knack for taking a good walking lead and being able to steal a base. Carlos Lee, who I coached in Milwaukee, is another; he’s a big guy and not a burner, but he can run the bases. The good base stealers, just like good baserunners, learn to be good by working at it. We encourage everyone, even runners who aren’t that fast, to work on baserunning. I knew I wasn’t speedy, but to score on a base hit from second, I knew that I had to learn how to take a good lead. So, I’d work on baserunning during batting practice and focus on trying to read the ball off the bat and try to get a good jump. You’ll see that a lot of good baserunners aren’t necessarily the fastest. Being a good runner comes down to instinct and focusing on getting a good lead and learning the pitchers.

We try to get our players to be aggressive on the bases. We want to find out who likes to run and who can run, so except for the catcher, everyone is encouraged to run; [they] have the green light here to run, unless we specifically take the “run” sign off. As for the New York Yankees, there’s only a handful of guys who run; with all those great batters and power, they don’t have to run. That goes for most of the American League; a lot of teams don’t have to run.

It pays to study the pitchers. Sometimes they’ll tip off when they’re going to the plate and not realize it. Some pitchers will tip off their pitches by setting themselves with their hands away from their body and follow with a fastball or set themselves with their hands closer to the body, which means an off-speed pitch. Throwing an off-speed pitch means they need to get a better grip on the ball, which means that sometimes they’ll keep their hands closer to their body. Knowing what pitch is on the way can affect a lot, from the hitters to the baserunners.

There’s a lot that goes into the game that the average fan doesn’t realize. They think we come to the park at 4:00 P.M., take batting practice, and then play the game and go home. But a lot of these players are here at noon or 2:00 P.M. and taking batting practice, spending time in the indoor cage, or stretching. And you have guys watching video. A lot is going on.

There’s a lot going on during the game as well. We watch the pitchers and watch the opposing coaches and try to pick up the signs. All of a sudden we’ll know they’re about to hit and run, or steal. And then they’ll know we have their signs, and they’ll change ’em.

Sign stealing is a big part of baserunning. I talk to our catchers all the time about keeping their arms in enough when giving the signs so the runner and the first-base coach can’t see. The only guys who should be able to see your signs are the pitcher, shortstop, and second baseman. Catchers can get lazy and keep their legs apart, and boom, the other team knows their signs. I even remember a time when I was coaching a college team, and we picked up the sign because the opposing catcher was keeping his elbow close to his body when he wanted a fastball, and away from his body for a breaking ball. We pummeled the poor kid on the mound, and he had no clue what was happening. His catcher was giving the signs away. But picking up these things is the fun part of the game.