Can You Read, Judge Landis?

This article was written by Larry Lester

This article was published in From Rube to Robinson: SABR’s Best Articles on Black Baseball (2021)

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in Black Ball: A Negro Leagues Journal, Vol. 1, No. 2 (McFarland & Co., Fall 2008).

Premise

By the late 1930s, and particularly during the years of US involvement in World War II, segregation in sport and society was a topic of increasing public interest. Nationalism had at least briefly trumped racism when Joe Louis and Jesse Owens emerged triumphant against the Germans. Within baseball, members of the media had loudly called for integration, which some major league managers, players, and even owners publicly supported. And as big leaguers went off to war, leaving behind diluted rosters and flagging attendance, calls for the signing of Black players grew more persistent. In spite of these facts, some researchers contend that Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis must be held blameless for extending the color line; segregation, they argue, was a cultural wrong, and the time was not yet ripe to change it. This article advances a counter-argument, presenting evidence that Landis repeatedly disregarded calls for integrated play and in some instances acted to perpetuate segregation.

“The only thing necessary for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing.” — Edmund Burke (1729–97)

This commentary is a counter response to Norman Macht’s “Does Baseball Deserve This Black Eye?” at SABR’s 37th annual convention in St. Louis. His presentation looked at the attitudes and societal restrictions on racial integration prevailing in the era of Judge Landis’s baseball leadership, giving Landis and other team owners an excuse from America’s social ills. Meanwhile he stated there was no proof that Landis was against the integration of baseball and added, if there was, David Pietrusza’s extensive biography would have indicated this. Macht also argued that team owners were “businessmen, not social reformers” and therefore exempt from their responsibility as laissez-faire thinkers. A request for a printed copy of Mr. Macht’s presentation from SABR’s research library was not honored. Also note, minutes of the leagues’ executive board meetings, currently housed at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, are unavailable to researchers, as Major League Baseball has not “signed off” on their release.1 This counterargument to Landis’s position on integration is based on the premise of Nobel Prize–winning author Toni Morrison that “Racism is a scholarly pursuit, it’s taught, it’s institutionalized.”2

The nation’s credo, “All men are created equal,” was a revolutionary idea which became the core of American beliefs. Somewhere along the way, these self-evident truths that were endowed by our Creator lost their way. As Americans strayed from this creed, Hall of Fame writer Sam Lacy said, “Some people were created more equal than others.”3 Nine score and seven years since the Declaration of Independence, these unalienable rights are still a dream for some, as some are reminded by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

One such dream was to play the game of baseball. “Next to religion, baseball has furnished a greater impact on American life than any other institution,” boasted President Herbert Hoover. 4 Several years before dreamer Jackie Robinson crossed the imaginary but real color line, there was a campaign initiated by wartime activists and writers to integrate this institution, known as the national pastime. This crusade to integrate baseball targeted Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, named after a Civil War battle of Confederate victory. For almost a quarter of a century, Commissioner Landis ruled apartheid baseball with a dictatorial influence that, among other things, prevented any man with a suntan from playing in his sandbox.

You were not welcomed if your name had ethnic overtones like Tyrone, Torriente, Clemente, Minoso, Dihigo, Ichiro, or Nomo. However, you would receive an invitation if you were in the image of the owners.5 The Baseball Register would humbly display one’s ancestry as Solvenian (Erv Palica), Scotch-Irish (Eddie Robinson), Irish Lithuanian (Barney McCosky), Irish Dutch (David Jolly), French Scotch-Irish (Ransom Jackson), French Canadian (Buddy Rosar), Czech German (Hal Newhouser), Danish Irish (Jack Jensen), Swiss English German (Dick Sisler), and Austrian-Hungarian (Hank Bauer).6

For someone looking at one’s self through the eyes of another, race often becomes a creature defined by one’s mind and twisted for its own discriminating purposes. Racism in baseball was not a static force. It transformed itself as it went from host to host, infecting our beloved game of peanuts and crackerjacks.

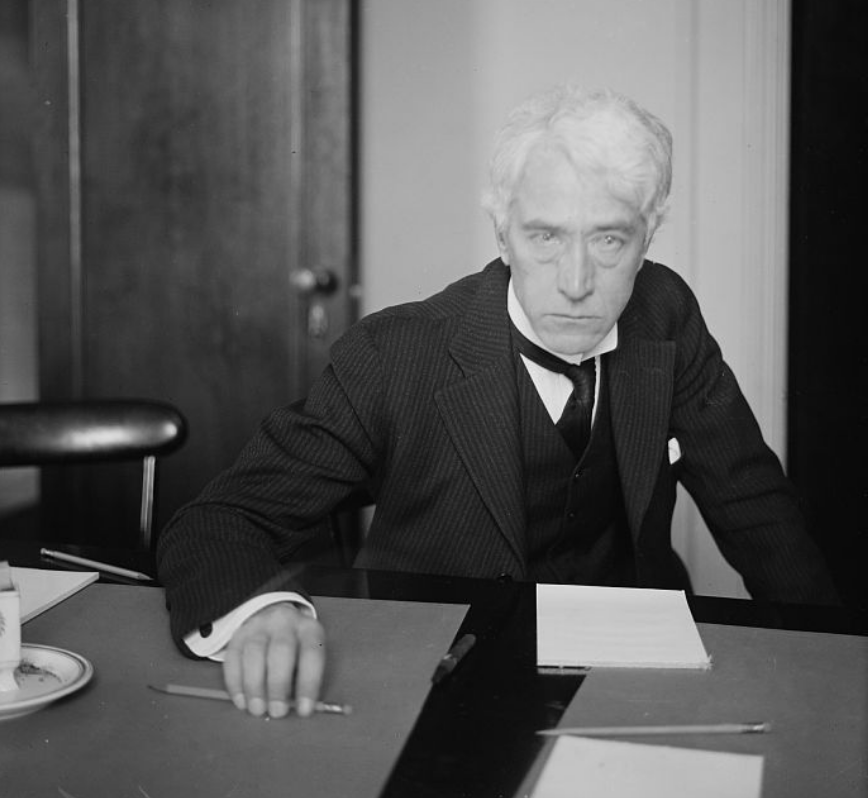

Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis served as baseball’s commissioner from 1920 until his death in 1944. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

The Formative Years

A central figure in our segregated game was Kenesaw Mountain Landis. He was meagerly educated and minimally trained for the profession of law. Landis was described by historian Harold Seymour as a “scowling, white-haired, hawk-visaged curmudgeon who affected battered hats, used salty language, chewed tobacco, and poked listeners in the ribs with a stiff right finger.”7

Born in Millville, Ohio, Landis grew up in Logansport, Indiana. After failing an algebra class the Hoosier dropped out of high school. Later he taught himself dictation to secure a job as a courtroom reporter for the Cass County (Indiana) circuit court. Landis earned his high-school diploma in night school and later received his bachelor-of-law degree, in 1891, from the Union Law School in Chicago, now part of Northwestern University. Landis boasted to Tom Swope of the Cincinnati Post, “You Know, Tom, I never went to college myself. Mighty few persons know that, but it’s a fact. I started my law course at the Y.M.C.A. Law School in Cincinnati and finished it at a similar school in Chicago.”8

In 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt appointed high-school dropout Landis as a federal judge for Illinois. In 1907, Landis gained national fame when he ordered the nation’s wealthiest man, John D. Rockefeller, to testify in the highly publicized suit against his Standard Oil Company for conspiring with railroads to fix prices. Landis smacked the Rock with an unprecedented fine of more than $29.24 million. Rockefeller won the case on appeal and never paid the fine.

In 1914 and 1915, Landis sat on the antitrust suit brought against Major League Baseball by the outlaw Federal League. Trustbuster Landis suddenly found himself on the side of monopoly and strategically withheld a decision in the case, eventually forcing the Feds to accept a settlement and fold their tents, thus preserving the hegemony of the two leagues. Baseball kept its monopoly and Landis was the hero of the club owners.

Seymour added: “Landis had a deep affection for baseball and looked upon the players more as heroes than as employees. He had a keen aversion to organized labor, liquor, and the New Deal. The rub was that he permitted his personal dislikes to warp his judicial objectivity.” 9

With damage to the national pastime’s brand and image brought on by the infamous Black Sox Scandal in the 1919 World Series, baseball sought a remedy. Although the eight players suspected of fixing the series had been acquitted in judicial court, the Judge used his subjectivity to argue that the need to clean up baseball’s reputation took precedence over any legal judgments. His no-nonsense approach to matters made him an ideal choice to preside over baseball’s kangaroo court. His salary rose from $7,500 as a judge to $50,000 as baseball commissioner. However, Landis would only take the difference of $42,500 for his sovereignty.10

Landis restored America’s faith in baseball, but at the price of making the game paternal and sacred. In his first years as commissioner, the monarch of segregated baseball, with complete authoritative influence, banished for life 19 players, two owners, and one coach,11 and at one time he ruled 53 players ineligible. Often accused of a restricted outlook on America’s game, particularly in matters of race relations, Landis in 1921 issued a decree to prevent completely White major-league teams, especially the Babe Ruth All-Stars, from competing against Black teams in the postseason.12 The commissioner threatened to ban the Bambino, Bob Meusel, and Wild Bill Piercy if they played against Oscar Charleston’s Colored All-Stars (in the Southern California League). After the club lost to the Charleston club, Landis withheld their World Series pay and suspended the Yankee bad boys Ruth and Meusel (the team’s second leading hitter) and Piercy (a third-string pitcher) for 39 days, or until May 20 of the 1922 season, for not adhering to his dictum.13

Landis’s new ruling prevented more than three players from a single team to compete against the Black teams, with such games being promoted as “exhibition” games, to diffuse any inherent meaning of a meaningful contest. The 1922 postseason revealed the Bacharach Giants beating the New York Giants twice and the St. Louis Stars defeating the Detroit Tigers two out of three games. Meanwhile the Hilldale Club (of Darby, Pennsylvania) took five of six games from the Philadelphia Athletics, and the Chicago American Giants split two games with the Detroit Tigers.14

The commissioner’s policies were often accepted, if not applauded, by the baseball nation. While writers often viewed Landis as harsh and narrow-minded, he was generally popular because of his steadfast efforts to maintain the integrity of the game, which was seriously questioned during the World Series scandal. His rule became nearly absolute with the 1922 Supreme Court decision that exempted the major-league cartel from antitrust legislation.

By 1926, Washington Post writer Shirley Povich summed up the icon’s growing legacy in his column “Following Through”:

There is a man of mystery. Mysterious in the manner that he so completely dominates his associates, who, in his present undertaking, are his employers. And he makes them like it. Sixteen major league magnates, supposed to be business men and drivers of hard bargains, are so completely under the thumb of the man with the funny name and the well-deserved title that it is strange if not mysterious or weird. . . .

Judge Landis is either the possessor of some spark of personality indescribable that puts him far ahead of his time or he is a grand hoax.

Landis had an uncanny capacity to influence and intimidate people and major league baseball “clothed him with the full power of his office.” However, Povich observed,

Why the sixteen major league magnates fear the displeasure of the man whom they elected to arbitrate in their own cause is strange…. What sort of a man is he who, by his mere presence and demeanor and the dignity that goes with age, turns such an adverse situation into a rout of his enemies? Surely, he is no ordinary personage. It may be the very audacity of his methods in flaunting the authority of his employers that gains him their respect. They clothed him with the full power of his office . . . Judge Landis, some man.15

The Movement Starts

In his SABR presentation, Macht made the dubious claim that America was “not socially ready” for integrated play. In fact, history holds many examples of peaceful contests between Black and White teams as well as fully-integrated games. In 1925, the Ku Klux Klan No. 6 of Wichita, Kansas, played the local colored Monrovians, in a contest officiated by two Irish Catholics to avoid preferential treatment.16 There was no reported violence on or off the field in a victory for the Monrovians.17 Further evidence reveals that integrated team play in Wichita’s National Baseball Congress tournaments (in 1935, with extensive coverage by The Sporting News) and the Denver Post Tournament (in 1934) occurred without incident.18 There are numerous examples of incident-free integrated play throughout Landis’s tenure as commissioner.

In 1939 the National Baseball Hall of Fame opened in Cooperstown, New York, to honor baseball’s greatest (White) players, managers, and executives. Meanwhile, some members of the mainstream press were outraged at the absence of African American ballplayers that were not invited to “The Show” and had no hope for Cooperstown fame. Jimmy Powers for the New York Daily News wrote to Bill Terry, manager of the New York Giants, who had finished in fifth place in 1939 with a 77–74 won-lost record: “Get yourself a batch of Satchel Paiges, Josh Gibsons and other truly great ball-busters. You’d find the Polo Grounds jammed with new and enthusiastic rooters. . . . Bill, you can make yourself the biggest man in baseball and I mean big. There is absolutely no law on your books barring a decent, hard-working athlete simply because his skin is a shade darker than his brother’s. . . . You’ve got a pennant at your fingertips.”19

A few months later, the Philadelphia Record made the same request to their local teams: “The Athletics and Phillies can be pennant contenders—not next year or the year after or five years from now—but immediately. Experienced players are available who could strengthen the A’s shaky pitching staff, give the Phillies the batting punch they need. These players could make potential champions out of any of the other also-rans in either major league. . . . But they are Negroes, and organized baseball says they can’t come in. . . . But no vote is ever taken on the subject, no manager or owner dares defy the Jim Crow tradition which in the past has been the most inflexible unwritten law in the game.” 20

The unwritten law generously allowed the 1939 Phillies to finish last with a 45–106 won-lost record, 50 1/2 games back. Their offense generated a paltry .317 on-base percentage. They failed to produce a batter with at least 70 RBIs or double-digit homers. On the other side of Philly, the A’s pitching staff had a 5.79 ERA and only one 10-game winner (Lynn Nelson), as they finished in seventh place in the American League with a 55–97 won-lost record. Yet the city of Brotherly Love did not extend any love for their Black brothers.

As more attention than ever was focused on the integration issue, the last year of the decade proved to be a pivotal point for baseball in America, particularly Black baseball. With the exclusion of the Negro Leagues from the national pastime, it became a symbolic rip in the American flag. More press coverage and more campaigns questioned the so-called “gentlemen’s agreement” imposed by major-league owners.

Another thought came from Shirley Povich in his Washington Post column “This Morning”:

There’s a couple of million dollars worth of baseball talent on the loose, ready for the big leagues yet unsigned by any major league clubs. There are pitchers who would win 20 games this season for any big league club that offered them contracts, and there are outfielders who could hit .350, infielders who would win quick recognition as stars, and there is at least one catcher who at this writing is probably superior to Bill Dickey. . . .

Only one thing is keeping them out of the big leagues—the pigmentation of their skin. They happen to be colored. That’s their crime in the eyes of big league club owners. Their talents are being wasted in the rickety parks in the Negro sections of Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, New York, Chicago and four other cities that comprise the major league of Negro baseball. They haven’t got a chance to get into the big leagues of the White folks. It’s a tight little boycott that the majors have set up against the colored player.

Povich directed responsibility at the commissioner: “It’s definitely understood that no club will attempt to sign a colored player. And, in fact, no club could do that, because the elasticity of Judge Landis’ authority would forbid it.”21 Since Landis had such absolute authority from the owners no one would defy this unwritten rule without some indication from the commissioner that is would be acceptable.

Truths, Lies, & Alibis

In the summer of 1939, Wendell Smith launched a series of eight articles, in the Pittsburgh Courier, covering interviews with 40 players and eight managers requesting their opinions on integration. Smith strongly felt that Landis “never used his wide and unquestionable powers to do anything about the problem” and instead played a subtle “fence game.” 22

In the summer of 1939, Wendell Smith launched a series of eight articles, in the Pittsburgh Courier, covering interviews with 40 players and eight managers requesting their opinions on integration. Smith strongly felt that Landis “never used his wide and unquestionable powers to do anything about the problem” and instead played a subtle “fence game.” 22

Selected interview excerpts support this premise.

“If the question of admitting colored baseball players into organized baseball becomes an issue, I would be heartily in favor of it. I think the Negro people should have an opportunity in baseball just as they have an opportunity in music or anything else.” — William E. Benswanger, president, Pittsburgh Pirates23

“Yes, if given permission I would use a Negro player on my team. I have seen at least 25 Negro players who could have made the grade.” — Deacon Bill McKechnie, Cincinnati Reds manager, later Larry Doby’s coach (1947–49) with the Cleveland Indians24

“A few years ago, we played an exhibition game in Oakland, California, against a Negro all-star team. Satchel Paige, the fast ball wizard, pitched against us, and I’m telling you he was great. I said right there that he was as good as Dizzy Dean.” — Ernie Lombardi, Reds catcher, 1938 National League Most Valuable Player25

“I grew up in Philadelphia which was the hotbed of colored baseball. I saw any number of Negroes who should have made the big leagues. They had some of the best players I have ever seen on those teams.” — Bucky Walters, Reds pitcher, 1939 National League MVP26

“I certainly wouldn’t object to a good Negro ball player on our team. They have some of the best ball players I have ever seen. Although it’s none of my business, I don’t see why they are barred.” — Johnny Vander Meer, Reds pitcher who hurled back-to-back no-hitters in 193827

“Two years ago, I played in some exhibition games out on the Coast. I played in at least five games and I guess I saw at least six colored players whom I thought I could use in the big leagues.” — Doc Thompson Prothro, manager of the last-place Philadelphia Phillies28

“I saw two of the greatest ball players that ever lived, Rube Foster and Smokey Joe Williams. They were both pitchers and although I was just a kid, I was convinced that they were certainly good enough for the majors.” — Gabby Hartnett, Chicago Cubs manager, 1935 National League MVP and future Hall of Famer (1955) 29

“If some of the colored players I’ve played against were given a chance to play in the majors they’d be stars as soon as they joined up. Listen, Satchel Paige could make any team in the majors. He’s got everything a pitcher can have. Shucks, only his color holds him back. He could be plenty of help to some of these big league teams — I’m tellin’ you.” — Dizzy Dean, pitcher, 1934 National League MVP and future Hall of Famer (1953)30

“I’ve seen plenty of colored boys who could make the grade in the majors. I have played against some colored boys out on the coast who could play in any big league that ever existed. Paige, [Cy] Perkins, Suttles and Gibson are good enough to be in the majors right now. All four of them are great players. Listen, there are plenty of colored players around the country who should be in the big leagues. I certainly would use a Negro ball player if the bosses said it was all right.” — Leo Durocher, manager, Brooklyn Dodgers31

“Yes indeed, I’ve seen a number of Negro players whom I think were good enough for the majors. I rate Dick Lundy, Satchel Paige, Mule Suttles and [Robert] Clarke among the best players I have ever seen.” — Babe Phelps, Dodgers catcher, who hit .367 in 193632

“I’ve seen a whole gang who could make the grade. Paige, Gibson and Suttles are real big leaguers.” — Cookie Lavagetto, Dodgers third baseman, who would later play with Jackie Robinson in the majors33

“Most of the great players I’ve seen are through. However, I’d name [Oscar] Charleston, [Martin] Dihigo and [Carlos] Torriente. They were good enough for any big league team that ever existed.” — Charley Dressen, coach, Dodgers34

The overall opinion of 48 men was in favor of the acceptance of Black players and included acknowledgment of some talented tan players. Managers McKechnie, Prothro, and Durocher appeared willing to accept Black players on their respective teams, if permitted. In turn Lester Rodney, a White writer for the Communist newspaper New York Daily Worker, explained his motivation to end racism in baseball:

I belong to an organization which had as part of its party’s platform the ending of discrimination—as a dream. Even long before I joined that party, I had been a red-hot baseball fan and got to know about some of the great players who were not allowed to play in America’s national pastime.

I would go out and see the Kansas City Monarchs and Satchel Paige pitch and all. You couldn’t be a real baseball fan without knowing something was wrong there. Especially since my team, the Brooklyn Dodgers of the thirties, was pretty pathetic.35

Rodney congratulated Smith for his efforts and noted the numerous statements by players and managers welcoming desegregation. Lambasting the apologists for blaming White fans and ballplayers for wanting the color line, Rodney and others also pointed out to the ownerships the mega-attendance at games between Negro League and MLB all-star teams.

Gate receipts at Negro League games also drew attention. In 1941, the East–West all-star game hit an all-time high in attendance with 50,256 fans and opened the curtains for Ed Harris of the Black-owned Philadelphia Tribune to pose the integration question to the moguls of major league baseball and their reasoning for ignoring Black players.

You read about the 50,000 persons who saw the East-West game and the thousands who were turned away from the classic and you get to wondering what the magnates of the American and National League thought about it when they read the figures. Did any of them feel a faint stir in their hearts; a wish that they could use some of the many stars who saw action to corral some of the coin evidently interested in them? Or did they, hearing the jingling of the turnstiles in this, one of the good seasons baseball has had, just dismiss the motion and reserve the idea of Negro players in the big league until the next time there is a depression and baseball profits began to decline? Fifty thousand people at any baseball game, World Series included, is no small figure.36

As years went on, this economic argument began to overshadow major league owners’ other reasons for rejecting Black players.

Can You Read?

In 1942, a campaign called “Can You Read, Judge Landis?” was initiated by Rodney and the Daily Worker. With the war effort and national pride foremost in American minds, many socially activist groups campaigned for the inclusion of Blacks into baseball.

Joining the fight was columnist Eddie Gant of the Chicago Defender. In his column “I Cover the Eastern Front” he claimed Landis had always “disliked the colored player and colored baseball” and had attempted to prevent the upcoming Satchel Paige All-Stars from playing against a White all-star team, saying it was a phony relief game to benefit the war effort. Interracial games earlier that year had attracted 29,755 fans in Chicago, and 22,000 in Washington, D.C. Landis told major-league park owners not to rent their parks for these fundraisers.37 There was a conscious strategy to maintain apartheid baseball.

Concurrently, the Greater New York Industrial Union Council, representing more than half a million CIO trade unionists from more than 250 locals, unanimously passed a resolution to end apartheid in baseball. The resolution was sent to Judge Landis with a challenge to other trade unions to follow their example. The council’s resolution in part read:

Whereas, in the spirit of national unity, Americans from all sections of the country have united to end the discrimination against race, color or creed. . . . Whereas, President Roosevelt in his address to the nation has stressed the importance of ending discrimination to insure victory. . . . Be it resolved that we, the Greater New York Industrial Union Council . . . demand that Judge Landis end jim-crow in the big league baseball now.38

Another union, the United Packinghouse Workers of America, local 347, sent four resolutions to Judge Landis asking that the discrimination against Black players end as “it is the expression of Hilterism we are all seeking to destroy.”39 In June of 1942, a “Can You Read?” message was sent by the largest trade union in the United States, Ford Local 600 of the United Auto Workers (UAW). The Ford factory workers producing tanks and planes to defeat Nazism sent out telegrams and letters stating their belief that “National Unity embracing all races, colors and creeds is particularly necessary at this point in order to win the war against Fascism.” The Ford local had 15,000 Black workers, including board members and union leaders. More than 80,000 workers approved the resolution to Judge Landis, which read in part:

Whereas, Ford Local 600 UAW-CIO is opposed at all times to all forms of discrimination anywhere because of race, color or creed, and Whereas, Negroes are barred from playing in Major League baseball and Whereas, such leading baseball players as Joe DiMaggio, Bob Feller, Dizzy Dean and others have claimed that such Negro stars as Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson and others are capable of playing Major League ball, and Therefore be it resolved that Ford Local 600 goes on record against the ban of Negro ball players . . . and petition baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis to use his powers to lift this ban.40

By the middle of July, more than one million signatures had been gathered on a petition to Judge Landis to lift the color barrier. “I would say the petition drive was a success when a million signatures landed on Landis’ desk,” said Lester Rodney. “And we didn’t have a million Communists. These were people who were going to the ballpark and wanted to see justice. It played a role, but that didn’t make the difference. A lot of great people started to join in and making noise.”41

The “Can You Read?” campaign continued at movie houses. The debut of the motion picture Pride of the Yankees, about Lou Gehrig’s career, was bombarded with pamphlets titled “In the Spirit of Lou Gehrig,” calling for an end to Jim Crow. Roughly 20,000 leaflets were distributed to ten New York theaters with a statement that Gehrig made in 1938: “I have seen and played against many Negro players who could easily be stars in the big leagues. I could name just a few of them like Satchel Paige, Buck Leonard, Josh Gibson and Barney Brown who should be in the Majors. I am all for it, 100%.”42 And there still came no response from the commissioner’s office.

The Communist Party was diligent in its campaign to bring racial equality to the forefront. Historian Henry D. Fetter noted, “The Communist paper’s sports staff approached the breaking of baseball’s color line with the belief that class, not race, provided the determinative fault line on American social life, and that racism was instigated by the bosses to foment division between White and Black workers, including baseball’s working class: the players.”43

Meanwhile, marching activists, organized by the Harlem-based League for Equality on Sports and Amusements, routinely picketed downtown Manhattan with signs that read: “IF WE CAN STOP BULLETS, WHY NOT BALLS?” and “WE CAN PAY, WHY CAN’T WE PLAY.”44

Jim Crow Must Go!

For years, similarly black ink came from Joe Bostic (Harlem People’s Voice), Ches Washington (Pittsburgh Courier), Wendell Smith (Pittsburgh Courier), Jimmy Powers (New York Daily News), Sam Lacy (Chicago Defender, Baltimore Afro-American), Ed Harris (Philadelphia Tribune), Eddie Gant (Chicago Defender), Shirley Povich (Washington Post), and others to further the cause of “one-game-for-all.”

On May 6, 1941, the day before the highly-attended Satchel Paige-Dizzy Dean matchup in Chicago, Rodney addressed Judge Landis, pressuring the commissioner to officially react to the apartheid issue in baseball. “We had always pointed to Landis as the one who had the authority to end the color line. But now we really put the spotlight on him,” said Rodney. “The war was on and Blacks were being sent overseas and were among the casualties. So I decided to write Landis an open letter using that as a theme. We ran it under the headline ‘TIME FOR STALLING IS OVER, JUDGE LANDIS.’ This was about a month before I was drafted.”45

Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis

Commissioner of Baseball

333 North Michigan Ave.

Chicago, Illinois

The first casualty lists have been published. Negro soldiers and sailors are among those beloved heroes of the American people who have already died for the preservation of this country and everything this country stands for—yes, including the great game of baseball.

So this letter isn’t going to mince words.

You may file this away without comment as you already have done to the petitions of more than a million American baseball fans. You may ignore it as you have ignored the clear statements of the men who play our National Pastime and the men who manage the teams. You may refuse to acknowledge and answer it as you have refused to acknowledge and answer scores of sports columns and editorials in newspapers throughout the country—from Coast to Coast, Philadelphia, New York and down to Louisville and countless smaller cities.

Yes, you may again ignore this. But at least this is going to name the central fact for all to know.

You, the self-proclaimed “Czar” of Baseball, are the man responsible for keeping Jim Crow in our National Pastime. You are the one who, by your silence, is maintaining a relic of the slave market long repudiated in other American sports. You are the one who is refusing to say the word which would do more to justify baseball’s existence in this year of war than any other single thing. You are the one who is blocking the step which would put baseball in line with the rest of the country, with the United States government itself.

There can no longer be any excuse for your silence, Judge Landis. It is a silence that hurts the war effort. You were quick enough to speak up when many Jewish fans asked for the moving back the World Series opening by one day to avoid conflict with the biggest Jewish holiday of the year . . . quick to answer with a sneering refusal. You certainly made it clear then that you were the one with the final authority in baseball. You certainly didn’t evade any responsibility then.46

America is against discrimination, Judge Landis.

There never was a greater ovation in America’s greatest indoor sports arena than that which arose two months ago when Wendell Willkie [a liberal-minded Republican who lost the presidential election to FDR in 1940], standing in the middle of the Madison Square Garden ring [after Louis defeated Buddy Baer the night of January 9, 1942], turned to Joe Louis and said, “How can anyone looking at the wonderful example of this great American think in terms of discrimination for reasons of race, color or creed?

Dorie Miller, who manned a machine gun at Pearl Harbor when he might have stayed below deck, has been honored by a grateful people.47 “The President of our country has called for an end to discrimination in all jobs.”48

Your position as big man in our National Pastime carries a much greater responsibility this year than ever before and you can’t meet it with your alliance. The temper of the worker who goes to the ball game is not one to tolerate discrimination against 13,000,000 Americans in this year of the grim fight against the biggest Jim Crower of them all—Hitler.

You haven’t a leg to stand on. Everybody knows there are many Negro players capable of starring in the big leagues. There was a poll of big league managers and players a couple of years ago and everybody but Bill Terry agreed that Negro players belonged in the big leagues. Terry is not a manager anymore and new manager Mel Ott, who hails from Gretna, Louisiana, is one of the players who paid tribute to the great Negro stars.

Bill McKechnie, manager of the Cincinnati Reds, set the tone for all the managers when he said, “I could name at least 20 Negro players who belong in the big leagues and I’d love to have some of them on the Reds if given permission.” If given YOUR permission, Judge Landis.

Manager Jimmy Dykes of the Chicago White Sox this spring was forced to tell two fine young Negro applicants for a tryout at the Pasadena training camp, “I know you’re good and I’d love to have you. So would the rest of the boys and every other manager in the big leagues I’m sure. But it’s not up to me.” It’s up to YOU, Judge Landis.

Leo Durocher, manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, who were shut out in Havana this spring by a Negro pitcher, has said, I wouldn’t hesitate a minute to sign up some of those great colored players if I got the OK. YOUR OK, Judge Landis. Get that?49

That’s the sentiment of player, manager and fan.

The Louisville Courier Journal50 of a month ago, entering the nationwide demand for the end of Jim Crow in our National Pastime said, “Baseball, in this war, should set an example of democracy. What about it, Mr. Landis?” Yes, what about it, Mr. Landis?

The American people are waiting for you. You’re holding up the works. And the first casualty lists have been published.

Yours,

Lester Rodney, Sports Editor, Daily Worker

New York City

One of the incidents Rodney refers to occurred on March 22, 1942, when Jackie Robinson and pitcher Nate Moreland appeared at Brookside Park in Pasadena, California, unannounced. Robinson, then 23, and Moreland, 25, requested a tryout from White Sox manager Jimmy Dykes. Dykes allowed them to go through the motions of fielding and pitching, giving words of encouragement, with no incentives of employment. Dykes claimed, “Personally, I would welcome Negro players on the Sox, and I believe every one of the other fifteen big league managers would do likewise. As for the players, they’d all get along too.”

Dykes added he felt that Robinson would be worth $50,000 to any major-league team and suggested they talk with Commissioner Landis and team owners about the possibility of gainful employment. Dykes wrote: “There is no clause in the baseball constitution, nor is there anyone in the by-laws of the major league which prevents Negro baseball players from participating in organized baseball. Rather, it is an unwritten law. The matter is out of the hands of us managers. We are powerless to act and it’s strictly up to the club owners and in the first place Judge Landis to start the ball a rolling. Go after them!”51 The Daily Worker, under the banner “‘Get After Landis, We’d Welcome You,’ Sox Manager Tells Negro Stars,” was the only newspaper to cover the event.)

Lester Rodney was not finished with the baseball czar:

After [the letter to the commissioner] we kept blasting away at Landis every chance we got. ‘Can You Read, Judge Landis?’ ‘Can You Hear, Judge Landis?’ and ‘Can You Talk, Judge Landis?’ in huge headlines. . . .

One time I noticed the attendance figures for a game between the Kansas City Monarchs and a team of former Big League All-Stars at Wrigley Field in Chicago. So out of curiosity, I checked the attendance of the White Sox-Detroit doubleheader being played in Chicago the same day. Well, the Monarchs-All-Star game, with Satchel Paige pitching, had outdrawn the White Sox-Tiger doubleheader by more than ten thousand fans. We turned that into a “Can You Count, Judge Landis?” piece. All these [articles] ran with our biggest headline type, above the masthead.52

A juggernaut of Black journalists, including Joe Bostic, Eddie Gant, Ed Harris, Sam Lacy, Alvin Moses, Ches Washington, Rollo Wilson, Fay Young, Dan Burley, and others, supported Wendell Smith’s strong effort in the early thirties to end segregated baseball. Following Smith’s lead, the Daily Worker published more articles about the need to integrate baseball than any other newspaper.53 In fact, in 1937, the Daily Worker published more than fifty articles on the issue and nearly a hundred more in 1938. 54 Rodney’s published letter to Landis and headline articles, along with signed petitions, had perhaps encouraged Judge Landis to make his first official statement on the race question. On July 17, the Los Angeles Times and several newspapers released Landis’s duct-tape testament to end the debate:

There is no rule against major clubs hiring Negro baseball players. I have come to the conclusion it is time for me to explain myself on this important issue. Negroes are not barred from organized baseball by the commissioner and have never been since the 21 years I have served. There is no rule in organized baseball prohibiting their participation to my knowledge.

If Durocher, or any other manager, or all of them want to sign one or 25 Negro players, it is all right with me. That is the business of the manager and the club owners. The business of the Commissioner is to interpret the rules and enforce them.55

The above statement was provoked by an alleged statement by the often abrasive and fiery Durocher, manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers: “I would hire Negro players if permitted.”56

Headlines across America read “Landis’s O.K. on Negro Stars Is a Great Democratic Victory for All America,”57 “Commissioner Landis’s Emancipation Proclamation,”58 “and “Landis Clears Way for Owners to Hire Colored.”59 Fay Young of the Chicago Defender called Landis’s statement a “smokescreen for owner bigotry.”60

In response to the Los Angeles Times article, White writer Gordon Macker of the Los Angeles News asked Landis: “What does that mean? Not a damn thing. He has merely stated that there is no rule against Negroes playing in organized baseball. There never has been any rule against them playing.” Macker added, “The statement of the high commissioner is just a lot of words . . . just another case of hypocritical buck passing.”61

An explicit Jim Crow rule was unnecessary if major league owners silently agreed to keep non-White players out of the game. In effect, Landis was the only man in baseball with the power to end discrimination. His unwillingness to change the status quo or even address the racial climate is his true legacy, not because he acted but because he refused to take action. Landis defended baseball’s lack of a rule, when he should have been making a rule saying that baseball “shall not discriminate.”

Perhaps seeing a need to protect Judge Landis, The Sporting News’s J. G. Taylor Spink, who wrote the 1947 best-seller Judge Landis and 25 Years of Baseball, immediately claimed in his tabloid, “No value would come from discussing the race issue as the color line was in the best interests of both Black and White folks.”62

Courageous New York Giants all-star hurler Carl Hubbell, replying to Landis’s statement, said, “Yes, sir, I’ve seen a lot of colored boys who should have been playing in the majors. First of all I’d name this big guy Josh Gibson for a place. He’s one of the greatest backstops in history, I think. Any team in the big leagues could use him right now. Bullet Rogan of Kansas City and Satchel Paige could make any big league team. Paige has the fastest ball I’ve ever seen.”63

Alva Bradley, owner of the Cleveland Indians concurred, “Cleveland would consider Negro players.”64 His manager, Lou Boudreau (Larry Doby’s first major-league manager), mentioned that he had played with Negroes in competition and had no objection to having them on his team, but added, “It’s all up to Alva Bradley—he owns the team.”65

The Tryouts

Taking the initiative, William E. Benswanger, president of the Pittsburgh Pirates, scheduled a tryout for New York Cubans’ ace Dave Barnhill (actual age 28, reported to be 24), catcher Roy Campanella (age 20), and second baseman Sammy T. Hughes (actual age 31, reported to be 27), the latter two of the Baltimore Elite Giants. The tryout was originally scheduled for August 4 but was postponed accommodating the Pirates’ return from a road trip that day. “Negroes are American citizens with American rights and deserve all the opportunities given to a White man,” said Benswanger. “They will receive the same trials given to White players.”66

Taking the initiative, William E. Benswanger, president of the Pittsburgh Pirates, scheduled a tryout for New York Cubans’ ace Dave Barnhill (actual age 28, reported to be 24), catcher Roy Campanella (age 20), and second baseman Sammy T. Hughes (actual age 31, reported to be 27), the latter two of the Baltimore Elite Giants. The tryout was originally scheduled for August 4 but was postponed accommodating the Pirates’ return from a road trip that day. “Negroes are American citizens with American rights and deserve all the opportunities given to a White man,” said Benswanger. “They will receive the same trials given to White players.”66

Homestead (Pittsburgh) Grays owner Cum Posey had expressed his skepticism about the proposed tryouts. In an interview with sportswriter John P. McFarlane of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Posey excused the Pirates’ president: “We’ve known Bill Benswanger for years. It was through his father-in-law, the late Barney Dreyfuss, that we got into baseball. Bill is sincere and he may go through with this thing, but we imagine that he will not try out colored players until he is sure some of the other teams will do the same, and I hardly think this will be before next spring, if then.”67

Added approval appeared to come from National League president Ford Frick, who declared: “If a contract for a colored player came across my desk today, I would approve it, providing it was otherwise in order. There is nothing in the rules of baseball that I know of that would permit any other action.

“I state unequivocally that there is no discrimination against Negroes or anybody else per se, in the National League. And you can quote me on that.”

Frick pointed out that African Americans had a false impression of baseball’s attitude toward race relations, adding that “This is really a social problem, not a baseball problem. And it would be unfair to call on ‘organized’ baseball to solve it now or any other time.

“I don’t think that racial or any other kind of discrimination is right. In fact if I thought that the inclusion of Negroes in baseball would end racial discrimination in America, I would start right out today and crusade for it.”

Unwilling to step up to the plate, Frick would backslide with thoughts of entertaining the issue of equal access to public accommodations for Black players, explaining:

Baseball has nothing to do with discrimination against Negroes in hotels, on trains, in restaurants, training camps and other public places.

A colored player traveling with a White club would be subject to all kinds of embarrassments and humiliations which he would not ordinarily have to face while playing with his own people.

It should also be realized that a ball club is a highly trained group of athletes who live, sleep two in a room, eat, travel and fight their team battles in the ball parks of the nation for eight months a year. They play 154 games in all, 77 at home and 77 on the road. In addition, they have to spend from a month to six weeks in the South during a strenuous training period so that the players can quickly develop into a smooth-running athletic machine. Absence of one or more players from training camp might prove an insurmountable problem.

With some of these obstacles in view, however, I still say colored ball players will find no barriers in my office. They are welcome anytime.68

After three weeks of excuses and delays, the Pittsburgh Pirates asked Negro League officials, sportswriters, managers, and owners to select four players from the East–West game for tryouts. The short list became Campanella, Hughes, and Barnhill, along with Josh Gibson, Ted Strong, Hilton Smith, Satchel Paige, Willie Wells, Leon Day, Sammy Bankhead, Howard Easterling, Thomas “Pee Wee” Butts, Pat Patterson, and Bill Wright. The tryout was rescheduled for September 1, with Gibson, Wells, Day, and Bankhead as the chosen ones. The owners also selected eight alternatives, which included the original trio of Campanella, Hughes, and Barnhill plus Strong, Smith, Easterling, Patterson and Butts.69 Paige and Bankhead did not make the cut. With a change in the “game” plan, the Black press began to heavily advertise the attributes of the foursome.

Lacking skilled players like Paige, Bankhead, and other Black stars on August 22, the National League standings showed the Pirates in fifth place, four games behind the fourth-place Cincinnati Reds. Catching for the Pirates was 34-year old Al Lopez, batting .250 with 21 RBIs and a home run. Lopez was no competition for Gibson, who was hitting around .375 in his league. At shortstop the Pirates had Pete Coscarart, a utility player who hit for a .129 average for the Dodgers in 1941. It is doubtful Coscarart would have been a serious challenger to an all-star performer like Wells. Leon Day, who reportedly won 24 games the previous year, could really have helped the Pirates pitching staff. Truett “Rip” Sewell, already 35, had the top Pirates won-lost record, at 12–10. In their outfield, Maurice Van Robays, Vince DiMaggio, and Jimmy Wasdell all batted under .260. Bankhead would have been a welcome addition to this weak outfield, with his all-around power and speed.

The Homestead Grays proceeded to lose to the Kansas City Monarchs in the 1942 Negro World Series, as the Pirates finished up their season. Although Gibson would bat less than .200 in the series, he claimed, “I am in good shape for my try out with the Pittsburgh Pirates.”70 After several postponements, the tryouts never materialized. The Pirates management offered no excuses to the press, as they finished in fifth place (66–81), 36 1/2 games behind the pennant-winning St. Louis Cardinals.

The Cleveland Indians announced on September 2 they would offer tryouts to Cleveland Buckeyes manager and third baseman Parnell Woods (age 30, reported to be 26), outfielder Sam Jethroe (25, reported to be 22) and pitcher Gene Bremer (26), in the near future. John Fuster, sports editor of the Black-owned Cleveland Call & Post had arranged the tryouts. Indians vice president Roger Peckinpaugh would not give a definite date for the tryouts. Eventually, like the promised tryout by the Pirates, the Cleveland organization walked the plank of solidarity.71

New hope reigned during a September 15 meeting at the offices of the Brooklyn Dodgers. William T. Andrews, an assemblyman, and Father Raymond Campion, a Catholic Priest, met with Dodgers president Larry MacPhail for almost two hours. Others in attendance were former Negro League commissioner Ferdinand Q. Morton, Fred Turner of the NAACP, Dan Burley of the Amsterdam News, George Hunton of the Catholic Interracial Review, and Joe Bostic of the People’s Voice. As the race issue was presented again to MacPhail, he responded with a different tone: “Plenty of Negro players are ready for the big leagues. In five minutes I could pick half a dozen men who could fit into major league teams.” MacPhail added that he thought that “Negroes should have the opportunity not only to play in the leagues, but should have a lot of other opportunities, in employment, housing and other things.”72

MacPhail also said he was willing to book his Dodgers against the Negro League winner for a postseason championship if his Bums won the National League pennant. He also suggested use of Ebbets Field, along with a 60–40 split of the gate receipts between the winners and losers. Father Campion and Assemblyman Andrews emphasized that Cleveland and Pittsburgh had failed in their commitment to grant players an opportunity to make their teams. MacPhail voiced his criticism of those owners: “It’s not necessary to try them out. They’re ready and willing to go into the majors [now].”73 The sports section of the Daily Worker boasted in large, one-inch type on September 19, “DODGERS MAY PLAY MONARCHS, NEGRO LEAGUE CHAMPS, IN POST SEASON TILTS” 74 Like many earlier promises, this one failed to materialize, as the Dodgers finished two games out of first place.

The 1942 season brought success and failure. During the course of this season, 31-year-old Rodney became a private in the US Army. Daily Worker writer Nat Low took over command of Rodney’s fight and wrote his analysis of the battlefield: “We DID get the Landis statement, and whereas we DID get the campaign much favorable national publicity and whereas we DID get promises of tryouts from two major league owners—William Benswanger of the Pittsburgh Pirates and Alva Bradley of the Cleveland Indians—we DID NOT succeed in our main objective—to get Negro stars onto major league teams, in uniform.”75

Despite all the efforts of the press, writers found the patriotic pool too shallow to drown the gatekeepers in self-acknowledgment of righteousness, as they often provided a lifejacket of alibis. “If you ask any honest sportswriter, he will tell you Landis was a racist,” claimed Lester Rodney. “He was a cold man. He could at any time as Commissioner, have said ‘something is wrong with this game.’”76 The owners pointed fingers at the commissioner, while Landis held the owners accountable to hire whomever. The skeptics were right; the promised tryouts never took place.

Sam Lacy, a Spink Award Winner and the first African American member of the Baseball Writers Association of America (1948), summed up the situation best:

Baseball in its time has given employment to known epileptics, kleptomaniacs, and a generous scattering of saints and sinners. A man who is totally lacking in character has often turned up to be a star in baseball. A man whose skin is white, or red, or yellow has been acceptable. But a man whose character may be of the highest and whose ability may be Ruthian has been barred completely from the sport because he is colored.77

From an End, a Beginning

Before the public ever knew whether Judge Landis would “learn how to read” the signs of change, the commissioner died on November 25, 1944, with the color curtain still tightly drawn. His rule had been absolute. Although generally regarded as the perfect man to bring integrity back to baseball after the Black Sox scandal, Landis held the throne too long.

In general, mainstream Americans accepted the racial exclusion of African American players because baseball executives claimed there was no color line issue to address. In effect, they chose the path of least resistance by ignoring that a “gentleman’s agreement” needed to be addressed. With fear as a constant companion and controller of emotions, the Black man was deathly afraid of White supremacists and rightfully so. But where were the White brothers of truth and justice in the fight against the white sheets that projected purification of their dastardly deeds? Landis and his businessmen were about the business of keeping the status quo, despite prima facie evidence of any injustice.

Accordingly, a reviewer of renowned historian David Pietrusza’s 564-page biography Judge and Jury: The Life and Times of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis notes:

The work does have one glaring deficiency . . . with regard to the book’s chronicle of Landis and the efforts to integrate the game. I rather felt that this (certainly the most significant of any shortcoming of his reign) was given less than adequate coverage by the author. Others have written more authoritatively (including firsthand reporting of confrontations over the issue) about how intractable a foe Landis was of integration of the American pastime. This book not only ignores almost all of these, but glosses over the issue in general with little more than an apologist’s dismissal. From my perspective, this is an unpardonable transgression.78

Pietrusza wrote 26 pages in chapter 25, “You Fellows Say I Am Responsible,” to lightly touch on the race issue.

Another reviewer states:

Not content with praising Landis’s actions, Pietrusza also defends his omissions. For example, he absolves Landis of any significant degree of responsibility for preserving baseball’s color line. Pietrusza asserts that if Landis was the most important man in baseball never to hit or throw a curve, not to mention ahead of the game on the gambling front, he was no worse than even with it on the integration issue. To see Landis as the ‘George Wallace of baseball’ is to ‘oversimplify’ things and ‘exculpate’ the rest of the game’s hierarchy.79

Yes, the janitorial Judge cleaned up the game, but he held back the master key to apartheid baseball. This is confirmed by his successor, former Kentucky governor and senator Albert Benjamin “Happy” Chandler, who reported that,

For twenty-four years Judge Landis wouldn’t let a Black man play. I had his records, and I read them, and for twenty-four years Landis consistently blocked any attempts to put Blacks and Whites together on a big league field. He even refused to let them play exhibition games.

I was named the commissioner in April 1945, and just as soon as I was elected commissioner, two Black writers from the Pittsburgh Courier, Wendell Smith and Ric Roberts, came down to Washington to see me. They asked me where I stood, and I shook their hands and said, “I’m for the Four Freedoms,80 and if a Black boy can make it in Okinawa and go to Guadalcanal, he can make it in baseball.”81

The story of America’s unpardonable acceptance of racial weakness and our nation’s lengthy obedience in segregated and discriminatory practices toward African Americans is well documented. Sadly, Landis and his clan were never able to transcend the social constraints of the period, despite the willingness of baseball executives like Bill Veeck and Branch Rickey, or of other sports executives and owners like Paul Brown (Cleveland Browns), Dan F. Reeves (Los Angeles Rams), or Red Auerbach (Boston Celtics). As Voltaire, the French philosopher of social reform, would say, “Every man is guilty of all the good he did not do.”

Historically, the omnipotent Landis had unlimited authority, and tremendous influence, but he lacked the fortitude to put a little soul into the game. Landis and his converts controlled the monopoly of racial inclusion and exclusion, meanwhile providing a plethora of excuses for their refusal to act. Nonetheless, the quarter-century tenure of ultraconservative Landis as the Commish, in which he opposed night games, the farm system, and integration, was romanticized with a special selection to the Cooperstown Hall of Fame a month after his death in November of 1944.82 His plaque reads: “His Integrity and Leadership Established Baseball in the Respect, Esteem and Affection of the American People.” This appeared to be self-evident truth for some Americans, not all Americans.

As Landis lay on his deathbed in St. Luke’s Hospital in Chicago, the joint committee of the two leagues recommended Landis for reelection. Yes, another seven-year term to begin January 12, 1946, on the expiration of his current term.83 Before the one-year anniversary of Landis’s death, Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey signed Jackie Robinson to a minor-league contract with the Canadian-based Montreal Royals, literally changing the faces of major-leaguers and the racial landscape of America forever. Some say Judge Landis and Babe Ruth changed baseball. Others believe two men with one voice, Branch Rickey and Jackie Robinson, changed America!

LARRY LESTER is co-founder of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and serves as chairman of SABR’s Negro League Research Committee. Since 1998, he has organized the annual Jerry Malloy Negro League Conference, the only scholarly symposium devoted exclusively to Black Baseball. He is the author of “Rube Foster in His Time,” “Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game 1933–1953,” “Baseball’s First Colored World Series: The 1924 Meeting of the Hilldale Giants and Kansas City Monarchs,” and “The Negro Leagues Book” (with Dick Clark), which has been updated in a second volume (with Wayne Stivers) available on Kindle. Lester lives in Raytown, Missouri. Lester is winner of the 2016 Henry Chadwick and 2017 Bob Davids awards.

Notes

1 Email from Erik Strohl, curator at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y., dated April 25, 2008. The author attempted to obtain a printed copy of Macht’s presentation from SABR’s Research Library, but it was not available. Hence, references to the talk are from the author’s notes.

2 E.B. Washington, “Toni Morrison Now,” Essence, October 1987, 58–60.

3 Sam Lacy, interview with author in Washington, D.C., October 14 , 1993.

4 Paul Dickson, Baseball’s Greatest Quotations (New York: Harper Collins, 1992), 187.

5 The owners of major league teams in 1944 were Sam Breadon (St. Louis Cardinals), Bill Benswanger (Pittsburgh Pirates), Powel Crosley Jr. (Cincinnati Redlegs), Philip K. Wrigley (Chicago Cubs), Horace Stoneham (New York Giants), J. A. Robert Quinn (Boston Braves), James and Dearie Mulvey (Brooklyn Dodgers), Robert R. M. Carpenter (Philadelphia Blue Jays), Donald Lee Barnes (St. Louis Browns), Walter Briggs Sr. (Detroit Tigers), Larry MacPhail, Dan Topping, and Del Webb (New York Yankees), Tom Yawkey (Boston Red Sox), Alva Bradley (Cleveland Indians), Connie Mack (Philadelphia A’s), Grace Comiskey (Chicago White Sox), Clark Griffith and George H. Richardson (Washington Senators). Minority owner and general manager William DeWitt of the American League champion St. Louis Browns, a one-time Branch Rickey aide with the Cardinals, was voted The Sporting News Executive of the Year. Our knowledge of individual owners’ positions on integration has been limited because minutes of the leagues’ executive board meetings have been unavailable to researchers.

6 Baseball Register (St. Louis: C. C. Spink & Son, 1953).

7 Harold Seymour, Baseball The Golden Age (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971), 367.

8 J. G. Taylor Spink, Judge Landis and 25 Years of Baseball (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1953), 7–8.

9 Seymour, Baseball: The Golden Age, 368.

10 Spink, Judge Landis and 25 Years of Baseball, 72

11 Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Major_League_Baseball_figures_that_have_been_banned_for_life#People_banned_under_Commissioner_Kenesaw_Mountain_Landis (accessed June 30 2008). Eight players for the Chicago White Sox were banned in 1920 for conspiring with gamblers to throw the 1919 World Series in the Black Sox scandal: “Shoeless” Joe Jackson, Eddie Cicotte, Lefty Williams, Chick Gandil, Fred McMullin, Swede Risberg, Happy Felsch, Buck Weaver. Other banned players included Joe Gedeon, St. Louis Browns; Eugene Paulette, Philadelphia Phillies; Benny Kauff, New York Giants; Lee Magee, Chicago Cubs; Hal Chase, New York Giants; Heinie Zimmerman, New York Giants; Joe Harris, Cleveland Indians; Heinie Groh, Cincinnati Reds; Ray Fisher, Cincinnati Reds; Dickey Kerr, Chicago White Sox; Phil Douglas and Jimmy O’Connell, New York Giants; William Cox and Horace Fogel, Philadelphia Phillies owners.

12 “Judge Landis Talks on Ruth’s Status,” New York Times, May 19, 1922.

13 Spink, Judge Landis and 25 Years of Baseball, 104–105.

14 Neil Lanctot, Fair Dealing and Clean Playing: The Hilldale Club and the Development of Black Professional Baseball, 1910–1932 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1994), 180.

15 Washington Post, December 18, 1926.

16 Brian Carroll, “Beating the Klan: Pre-integration Baseball Coverage in Wichita, 1920–1930,” The Baseball Research Journal 37 (2008), 51–61.

17 Bob Rives, “Klan and Colored Team to Mix on the Diamond Today,” Baseball in Wichita (Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2004), 58.

18 In 1869, the Philadelphia Pythians become the first Black team to defeat an all-White squad, defeating the cross-town rival City Items, 27–17.

19 Jimmy Powers, “Memo to Bill Terry,” New York Daily News, February 23, 1940. Earlier, Powers in his article of February 8, 1933, reportedly asked league and team officials if they objected to Black players in baseball. The only exception came from John McGraw, while John Heydler (NL president), Jacob Ruppert (Yankees owner), Gary Nugent (Phillies president), and ballplayers Lou Gehrig, Herb Pennock and Frankie Frisch welcomed the opportunity to have ballplayers join their teams if given permission by Judge Landis. With respect to Pennock, it’s curious that he was so open to integration in 1933, as in 1947 he was outspoken in his distaste for Jackie Robinson. Many sources have quoted Pennock ordering Branch Rickey to leave Robinson behind when the Dodgers visited the Phillies. In 1998, his racist actions reverberated as there was an outcry against a statue being erected in Pennock’s honor at his birthplace in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania.

20 Philadelphia Record, May 14, 1940.

21 Washington Post, April 7, 1939, 21

22 Brian Carroll, When to Stop the Cheering? The Black Press, the Black Community, and the Integration of Professional Baseball (New York: Routledge, 2007), 134.

23 New York Daily Worker, July 30, 1939.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

28 Pittsburgh Courier, August 5, 1939.

29 Pittsburgh Courier, August 12, 1939.

30 Ibid.

31 Pittsburgh Courier, August 5, 1939.

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid.

34 Ibid.

35 Lester Rodney, telephone interview with author, October 31, 1997.

36 Philadelphia Tribune, August 7, 1941.

37 Eddie Gant, “I Cover the Eastern Front,” Chicago Defender, June 13, 1942.

38 New York Daily Worker, June 8, 1942.

39 Chicago Defender, July 11, 1942.

40 New York Daily Worker, June 18, 1942.

41 Rodney, telephone interview with author, October 31, 1997.

42 New York Daily Worker, July 15, 1942.

43 Henry D. Fetter, “The Party Line and the Color Line: The American Communist Party, the Daily Worker, and Jackie Robinson,” Journal of Sports History, 28, no. 3 Fall, 2001, 384.

44 New York Times, April 18, 1945; Baltimore Afro-American, April 28, 1945.

45 Irwin Silber, Press Box Red (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2003), 79.

46 Yom Kippur is probably the most important holiday of the Jewish year. Yom Kippur means “Day of Atonement,” a day set aside to atone for the sins of the past year. The year before, 1941, two New York councilmen, Brooklyn Democrats Walter R. Hart and Joseph T. Sharkey, sent telegrams to National League president Ford Frick, American League president Will Harridge and Commissioner Landis, requesting movement of the first game of the subway series, between the Dodgers and the Yankees, to October 2 from October 1. The telegram read: “The Council of the City of New York unanimously passed resolution urging the postponement of the opening game of the World Series to Oct. 2, to enable thousands of sport-loving members of the Jewish faith to attend.” Although the Council sent telegrams to the league presidents, the feeble Ford Frick cried, “It’s entirely up to Judge Landis. It’s his party and I have nothing to say about it.” (New York Times, September 17, 1941, “Day’s Delay Asked in Start of Series”). Four days later, from his Chicago office Landis ruled that the World Series would open on October 1 as scheduled. The autocratic Landis mentioned that any person of the Hebrew faith could have a complete refund, including tax and the cost of postage if they sent their tickets by registered mail to him, in care of the National City Bank of New York (New York Times, “Series Dates Unchanged; Landis Denies Request,” September 21, 1941).

47 Miller was an African American cook in the United States Navy and a hero who went above and beyond the call of duty during the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. He dragged his dying captain, Mervyn Bennion, away from the shelling before manning a machine gun. The following year in June, Miller’s rank was raised to Mess Attendant First Class. On May 27, 1942, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, the commander in chief, Pacific Fleet, personally presented to Miller, on board aircraft carrier USS Enterprise, for his extraordinary courage in battle, the Navy Cross, second-highest honor awarded by the Navy, after the Medal of Honor. Sadly, Miller didn’t survive the war. In November of 1943, he died during an attack on the USS Liscome Bay.

48 More accurately, Executive Order 8802, signed in June of 1941 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, prohibited racial discrimination in national defense plants. This order required all federal agencies and departments involved with defense production to ensure that vocational and training programs were administered without discrimination as to “race, creed, color, or national origin.” All defense contracts were to include provisions that barred private contractors from discrimination as well. The executive order was issued in response to pressure from pre-King civil-rights activists Bayard Rustin and A. Philip Randolph, founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, who had planned the original march on Washington, D.C., to protest racial discrimination across America. Randolph suspended the march until Executive Order 8802 was issued. Some civil-rights critics felt betrayed by the suspension because Roosevelt’s proclamation only pertained to defense industries and not all the armed forces. Seven years later, in July of 1948, President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9981, expanding 8802 to include equality of treatment and opportunity in all the armed services, not just defense plants, becoming the first American institution to officially prohibit racial discrimination. The operative statement was: “It is hereby declared to be the policy of the President that there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin. This policy shall be put into effect as rapidly as possible, having due regard to the time required to effectuate any necessary changes without impairing efficiency or morale.” The order also established a committee to investigate and make recommendations to the civilian leadership of the military to realize the policy. In effect it eliminated all-Black Montford Point (New River, North Carolina) as a segregated Marine boot camp, with the last of the all-Black units in the United States military dismantled in September of 1954.

49 The New York Daily News had the largest circulation of any newspaper in the country at the time. In that paper on July 21, 1942, Hy Turkin wrote: “A casual remark made by Leo Durocher to Lester Rodney, Sports Editor of the Daily Worker, now in the Army, may do more for his place in history than all his shortstopping and managing histrionics. He said that he would hire Black players and this is like the tail of the tornado that has overwhelmed Judge Landis with two million signatures and threatens the democratization of our national pastime.”

50 Tommy Fitzgerald, Louisville Courier Journal, April 12, 1942.

51 New York Daily Worker, March 23, 1942.

52 Silber, Press Box Red, 82.

53 Chris Lamb, Blackout: The Untold Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Spring Training (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), x, xi.

54 Kelly Rusinack, “Baseball on the Radical Agenda: The Daily and Sunday Worker on the Desegregation of Major League Baseball, 1933–1947” (master’s thesis, Clemson University, 1995), 31, 57.

55 Los Angeles Times, July 17, 1942.

56 Ibid.

57 New York Daily Worker, July 18-20, 1942.

58 Pittsburgh Courier, July 25, 1942.

59 Baltimore Afro-American, July 18, 1942.

60 Chicago Defender, July 25, 1942.

61 “White Writer Hits Landis,” Chicago Defender, August 15, 1942, 21.

62 The Sporting News, August 6, 1942.

63 Los Angeles Times, July 17, 1942.

64 Cleveland Call and Post, July 24, 1942.

65 Ibid.

66 New York Daily Worker, July 28, 1942.

67 Pittsburgh Courier, August 22, 1942.

68 Pittsburgh Courier, August 8, 1942.

69 Pittsburgh Courier, August 22, 1942.

70 Pittsburgh Courier, September 17, 1942.

71 Cleveland Call and Post, September 2, 1942.

72 New York Daily Worker, September 19, 1942.

73 Ibid.

74 Ibid

75 New York Daily Worker, December 2, 1942.

76 Rodney, telephone interview with author, October 31, 1997.

77 Baltimore Afro-American, November 10, 1945.

78 Eric C. Moye, http://www.amazon.com/review/product/1888698098/ref=dp_top_cm_cr_acr_txt?%5Fencoding=UTF8&showViewpoints=1 (accessed June 30, 2008).

79 John C. Chalberg, review of Judge and Jury: The Life and Times of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, by David Pietrusza, Journal of Sport History 27, no. 2, 350.

80 The four freedoms were given by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s address to Congress on January 6, 1941. They were freedom of speech and expression, freedom of every person to worship God in his own way, freedom from want, and freedom from fear.

81 Peter Golenbock, Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Breaking Baseball’s Color Barrier, (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1984), 122.

82 “Senators’ Plea for More Night Games Denied as Landis Casts Deciding Vote,” New York Times, July 7, 1942.

83 “Judge Landis Dies; Baseball Czar,” New York Times, November 26, 1944, 78.