Miracle on Beech Street: A History of the Holyoke Millers, 1977–82

This article was written by Eric T. Poulin

This article was published in Fall 2021 Baseball Research Journal

Once a very sparsely settled farming community, Holyoke, Massachusetts’s geographic location on the banks of the Connecticut River was ideal for development, utilizing its ample source of hydroelectric power.1 A group of four wealthy executives from Boston, about 90 miles to the east, believed the South Hadley Falls of the river was large and powerful enough to potentially fuel many large manufacturing plants.2 This model of building industry on the banks of a large river had proven successful already in multiple other instances in Massachusetts, particularly involving the Merrimack River to the northeast.3 The damming of the Merrimack had led to the evolution of the thriving factory towns of Lowell and Lawrence — both of which were already established as national cotton manufacturing giants — as the planning of the Holyoke Dam was commencing.4

Holyoke was incorporated as a town in the year 1850, and the construction of a dam on the Connecticut began shortly thereafter.5 Immigrant labor from Ireland, Canada, Poland, Germany, and Italy was in no short supply. Holyoke truly thrived as a post-Civil War industrial city, making its mark most notably by producing high-quality paper products. The city’s population would increase from a mere 4,600 in 1885 to over 60,000 people just 35 years later. At one point, there were nearly 30 paper mills in operation, as well as factories that produced woolens, cotton, thread, silk, and industrial machinery.6

However, as was the case with other cities that were established purely on manufacturing during the industrial revolution, times would not always prove to be prosperous. Newer technologies and cheaper foreign labor would soon render many of these once-thriving mills obsolete. The first of the major employers to depart the city was the Farr Alpaca textile mill, which liquidated in 1939.7 Skinner Mill closed its doors in the late 1960s, although, as a slight consolation, the property site was eventually rehabbed and donated to the city to establish the now-popular Heritage State Park.8 Throughout the 1970s, most other major employers followed this lead, departing the city or closing altogether. As factory after factory shuttered — taking with them the employment opportunities that were once plentiful — the fate of a once-mighty industrial center would soon be in jeopardy.

While the closing of the mills was obviously the major factor leading to widespread unemployment in the city (16.7% by April 1975)9 and the concomitant social problems, a number of other factors also contributed. As the mills and the manufacturing jobs they provided became more of a scarcity, Holyoke also experienced a rather sharp increase of individuals entering the city looking for this exact type of employment. Throughout the first half of the 1970s, young servicemen would return home from the Vietnam War to discover that the jobs that had been available at the time of their enlistment were no longer in such supply. The guarantee of work opportunities that their parents’ generation had enjoyed in Holyoke had seemingly disappeared.

The city also experienced yet another tremendous ethnic migration during these years, as a large number of people from Puerto Rico and South America came to Holyoke seeking a better future for themselves and their families.10 Large ethnic migrations were nothing new to Holyoke — however, the employment opportunities that had been in great supply when the European and Canadian immigrants entered the city were no longer available. In fact, these migrants had the unfortunate timing of arriving at the exact period in the city’s history that these manufacturing jobs were disappearing. Couple this with the usual difficulties that face non-white migrants upon entering the United States — including barriers of language and culture, as well as hostility from those already residing here — and a great many tensions would prove to be inevitable.11

This is the backdrop that the Holyoke Millers of the Class AA Eastern League began playing ball in during the 1977 season. Elected officials believed that a minor-league baseball team in the city would lead to an increase in tourism revenue for Holyoke (it was estimated by multiple sources that a AA-level team would lead to an additional $250,000 for a community in 1977).12 Eastern League President Pat McKernan simply told city officials that if they could raise sufficient funds to complete necessary renovations to the municipally owned MacKenzie Field, he would deliver a franchise to Holyoke.13 A range of $65,000–108,000 was given to complete multiple tasks, including refurbishing locker-room facilities, construction of a concession stand, and the possible resodding of the field, while removing a cinder running track that cut through the outfield grass.14 As the city was in a bit of a down-and-out period, elected officials appeared willing to take a chance on something that could potentially reverse civic fortunes.

The city was able to muster the minimum $65,000 necessary to attract an Eastern League franchise. the Berkshire Brewers, a franchise that had been based in Pittsfield, Massachusetts 1965–1976, were convinced to depart the cozy confines of Wahconah Park for the “Paper City” of Holyoke. League president McKernan held true to his promise to deliver a team to Holyoke, aided no doubt by his connections that still existed with the Berkshire team. (He had formerly been the franchise’s president, a colorful tenure that included his wedding at home plate between games of a doubleheader, as well as an “attendance hunger strike,” a promotion where he would fast on each home game day if the team drew fewer than 500 fans — no small feat, considering he weighed in at more than 350 pounds.)15 Baseball fans were treated to an early holiday present, as city aldermen passed their final vote by a tally of 11–4 on December 21, 1976, to transfer the necessary funds to the Parks Department to bring minor-league baseball to Holyoke.16 The new franchise would be named the Holyoke Millers — a tribute to the industrial past upon which the city was founded.

As the city prepared itself for its first-ever season of AA baseball, it also found itself embroiled in a national headline-making controversy. On a nearly nightly basis, suspicious fires ripped through old tenements and factory buildings, leaving residents completely on edge. As the cause of these blazes was going undiscovered, law enforcement officials dispatched a Special Arson Squad to investigate all fires within Holyoke, to assess if any were of criminal nature.

The Special Arson Squad would make its first arrest on April 13, 1977 — the day the Millers played their first-ever game — a 15–2 exhibition victory against the neighboring University of Massachusetts in Amherst.17 Right fielder and leadoff hitter Gary LaRocque blasted the second pitch of the game 335 feet down the right field line for a home run, and with that, the Holyoke Millers were born.18

Two days later, the Millers began their 1977 Eastern League regular season in Pennsylvania on a Friday night against the Reading Phillies. This would be the first of a nine-game road trip to commence the season — a scheduling abnormality that was by design, intended to give the Holyoke Parks Department sufficient time to complete the necessary renovations that MacKenzie Field needed to host professional baseball.

Meanwhile, back in Pittsfield (the city that had previously been the franchise’s home), General Electric (the region’s major employer) announced the layoff of 225 employees.19 While Holyoke and Pittsfield were facing many of the same struggles at that time, there was seemingly no shortage of irony that these two events were occurring on the same day. Pittsfield’s sad loss — for one day, anyhow — was contrasted with Holyoke’s gain.

The starting lineup for the first-ever Holyoke Millers game was:

- Gary LaRocque, RF

- Billy Severns, CF

- Ike Blessitt, DH

- Gary Holle, 1B

- Jeff Yurak, LF

- Neil Rasmussen, 3B

- Ron Jacobs, C

- Ed Romero, SS

- Garry Pyka, 2B

Ron Wrona, P

Four hundred seventy fans (Reading officials had been hoping for 1,500–2,000) saw the young Millers build a 4–0 lead behind Wrona (one of the Millers’ most experienced pitchers, despite being in only his second year of pro ball) through five innings. However, the Phillies awakened with seven runs in the sixth inning, three of which were unearned. They would ultimately drop all four games in Reading, on their way to a 2–7 road trip to begin the season. Holding leads seemed to be particularly troublesome for the new team, as they would blow multiple 4–0 leads against Reading, as well as a 6–0 advantage at Jersey City. Holyoke’s bullpen would begin the season by dropping their first 11 decisions before a reliever would garner a single win.

The Millers were scheduled to make their home debut at Mackenzie Field on Sunday, April 24, 1977 — an afternoon contest against the Waterbury Giants. Competition for fans on that day would be fierce, as the game would be directly competing with a live performance by the locally popular polka ensemble, the Larry Chesky Orchestra, who were performing that afternoon at Mountain Park (a mid-sized Holyoke amusement park that was a popular destination from the late 1800s until its closing in 1987). In some ways, the rain that would postpone the game was a blessing of sorts, as a poor attendance showing at a home debut opener as a result of a polka concert might not exactly inspire.

Rather, the Millers took to the field at MacKenzie the following evening before a raucous 2428 fans — who were treated to a back-and-forth affair that saw the home side overcome a 5–0 deficit, before falling, 7–5.20 Future longtime major leaguer George Frazier would take the loss in relief. Designated hitter Ike Blessitt would provide the fireworks, bringing the Holyoke faithful to their feet, turning on a shoulder-high offering and blasting it 375 feet down the left field line for a game-tying two-run homer in the seventh.21

Blessitt proved to be the Miller that would bring the fans the most consistent excitement, leading the Eastern League in runs batted in for 1977, and winning the fan vote as the Most Popular Miller.22 His was an interesting story; while most members of the team were young prospects on the way up (Frazier and Romero both enjoyed lengthy major-league careers, while Jurak, Holle, Greg Eradyi, Doug Clarey, and Mark Bomback would all reach the show, if only for brief stints), Blessitt had already seen his career reach its pinnacle.

“The Blessitt One,” as he was known to the MacKenzie faithful, had already experienced a brief call-up to the Detroit Tigers at the end of the 1972 season, going hitless in five at bats over four games. Blessitt was well known throughout Michigan, having been a high school four-sport legend growing up just outside of Detroit. However, he was reassigned to the Tigers’ AAA affiliate during spring training of the following season, and was unfortunately involved in an off-field incident with manager Billy Martin in Lakeland, Florida, leading to the arrest of both men.23 According to Martin, he was trying to prevent Blessitt from getting into a late-night altercation with another man in a cocktail lounge, taking the young outfielder out to the parking lot to calm him down. The Lakeland police arrived on the scene shortly thereafter, made racial slurs to Blessitt as they arrested him, while also apprehending Martin, who claimed to be an innocent bystander.24

Given Martin’s well-documented history with numerous incidents of late-night barroom brawling (he was famously fired as manager of the New York Yankees for allegedly sucker-punching a marshmallow salesman in a bar at the end of the 1979 season25), the notion of him acting as a virtuous peacekeeper seems fictitious. Nonetheless, Blessitt would never reach the major leagues again following this evening in Lakeland.26

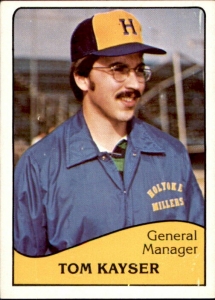

Blessitt’s blasts would be a lone early bright spot as the inexperienced Millers stumbled badly out of the gate, winning only three of the first 18 games of their existence.27 While victories were rare, the fan promotions you would expect at a minor-league ballpark certainly were not. The Millers held a “Guaranteed Win Day” (where fans would be admitted free of charge to the following day’s game if the Millers were unable to prevail),28 a “Mustache Night” (where 25-year-old general manager Tom Kayser promised to have his mustache shaved off if attendance surpassed 1500 for the game),29 while hosting appearances by Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Feller, as well as Max Patkin, a.k.a. “the Clown Prince of Baseball.” A “Beer Night” promotion was also considered, but never came to fruition.30

Nonetheless, something was clearly working — the Millers boasted the second-highest attendance figures in the Eastern League, drawing 61,171 fans for the season. They would rally to a respectable final record of 73–66, but would never realistically challenge the first-place West Haven Yankees, finishing 13½ games out of first.31 The team went their separate ways after the season and, with minor league salaries being typically low, many would go to work for the winter months. First baseman Gary Holle returned to his home in Watervliet, New York, to work as a legislative aide for a state senator, while doubling as the color commentator for Siena College’s basketball broadcasts. Outfielder Jeff Yurak would continue his education at California State University at Pomona, majoring in marketing. Pitcher Mark Bomback would return to his home in Fall River to work as a salesperson at a local clothing store.32

Perhaps the biggest accomplishment of the new team was the mere fact that Holyoke now had a POULIN: Miracle on Beech Street galvanizing institution to bring it together, even as the arson-related problems kept the community on constant edge. By the end of May alone, the city had endured 17 multiple alarm fires that year.33 In spite of all the efforts of the Special Arson Squad, the perpetrators of the majority of these blazes would never be determined. While New York City would ultimately gain some relief from their civic nightmare when David Berkowitz was arrested that August — ending the citywide fear of the Son of Sam murders — Holyoke experienced no such reassurance.

The Millers would open their 1978 season on the road at West Haven, dropping the first three games of the campaign to the Yankees. The home opener at MacKenzie on April 16 featured a ceremonial first pitch by Mayor Ernest Proulx, an offering that bounced multiple times before reaching the plate.

Based on the performance of the pitching staff during the year, Mayor Proulx could potentially have earned a spot in the rotation, as they posted the worst earned-run average in the Eastern League. In spite of the return of several fan favorites from the prior season (including the reigning EL home run champion Holle, along with Rasmussen, Yurak, and Bomback), the Millers greatly struggled to draw at the gate in 1978. An unusually cold and windy spring — even by Massachusetts standards — contributed to the reduced attendance, but the team’s performance on the diamond certainly didn’t help.

Rick Nicholson earned the first win of the season for the Holyoke nine on April 17 before 372 fans. Nicholson had been the top reliever in the New York-Penn League the previous season with the Newark Co-Pilots, posting a 5–2 record with 12 saves. This success was not replicated in Holyoke, as he compiled an ERA of 7.03 over 16 games.34

This would not be the lowest attendance figure of the season, as a May 2 contest against the Waterbury Giants would draw only 207 fans. Even the “Mustache Night” promotion couldn’t entice fans to the ballpark, as the same event that drew nearly 2000 fans in 1977 would only draw 372 in the new year.35

In all, the honeymoon period between Holyoke and the Millers was apparently over. They drew 13,000 fewer fans than the previous season, as the team stumbled to a fifth-place record of 61–76. The MacKenzie faithful were able to enjoy a fine campaign from future major league outfielder Marshall Edwards, as well as a career year from Eastern League MVP Yurak, and a franchise-record 60 stolen bases by second baseman Steven Greene. As management had identified the 45,000 mark as being the “break-even” point for attendance, the team managed to just scrape by in 1978.36

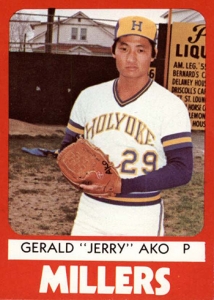

Gerald Ako, listed at 5’ 8” and 165 pounds, went 6–4 with a 2.88 ERA in 44 games for the Millers in 1980, including five starts. (Image: TCMA)

If the cliché about Rome not being built in a day is true, the 1979 Millers are certainly a prime example. The team improved its win total by a mere two games, while drawing 50,207 fans for the season — a modest improvement at best from the year before. This attendance number was surely aided by a mid-season appearance by the Famous Chicken — drawing 6,300 spectators (capacity at MacKenzie was listed at 4,100).37 However, the groundwork was seemingly laid for bigger things in the future, as Harry Dalton had taken over as general manager of the parent Milwaukee Brewers, an executive with a keen eye for recognizing young talent. Almost immediately, more major-leaguecaliber prospects would don the Millers colors.

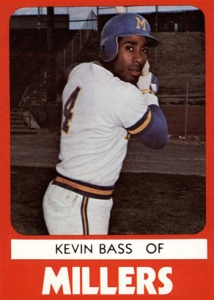

While four members of the pitching staff — Barry Cort, Sam Hinds, Larry Landreth, and Lance Rautzhan — would ultimately reach the big leagues, the most notable new member of the Holyoke nine would be twenty-year-old switch-hitting outfielder Kevin Bass. Bass would enjoy a fourteen-year major league career, highlighted by appearances in the postseason and All-Star Game in 1986 for Houston. His tremendous 1986 season would end unfortunately, however, as he struck out with two men on base in the 16th inning of Game Six of the National League Championship Series to end the game, sending the New York Mets to the World Series. As a young Miller, however, Bass enjoyed a respectable 1979. While his .263 batting average with eight home runs would be just the tip of the iceberg of his potential as a ballplayer, his Sammy Davis Jr. impersonation was already at a major-league level.38

Another item of note about the 1979 Millers was that they may have set an unofficial record for number of born-again Christians on one pro baseball team.39 Of the 21-man roster, 11 players identified as having recently found the Lord. Catcher Bill Foley told The Sporting News, “I’ve never before seen this many on one team! I felt a void in my life that needed to be filled”. Millers players filled this particular void with chapel services every Sunday and regular Bible readings throughout the season.40

The Millers faced some additional stiff competition for the local entertainment dollar throughout the second half of their season. After eight years of planning and negotiations, a million-square-foot shopping mall would open on July 5, 1979, in the Whiting Farms Road area of the city on the outskirts of town.41 At the time of its opening, the promise of increased job opportunities and an expanded tax base seemed to be trumpeting a new era of prosperity for the city.42 An unfortunate drawback of this new construction, however, would be the increased difficulty to attract business to downtown, as so many potential customers would instead opt for the convenience of one-stop shopping at the mall. Between the lack of businesses occupying downtown buildings, the ongoing arson fears, and an increase in crime as a direct result of unemployment, the center of the city became a very unpopular destination.

Switch-hitting outfielder Kevin Bass would go on to a 14-year major league career, including an All-Star Game selection in 1986 for Houston. (Image: TCMA)

Meanwhile, back on the ballfield, the 1979 season proved to be a dress rehearsal of sorts for much bigger things to come as the 1980s commenced. But in many ways, the biggest shift for the Millers would not occur on the field at all, as young general manager Tom Kayser made headlines when he purchased the team from Spike Herzig and the Northeastern Exhibition Company at age 27.43 The sale was announced a mere 24 hours before the Millers would open their 1980 season at MacKenzie against Reading. While an exact sale price was never announced, league officials stated it was less than the $45,000 an average Eastern League team was valued at in 1980. Sources say the sale price was closer to $30,000, as there was fear that another owner would buy the team and move it out of Holyoke. Kayser was seemingly given a bit of a hometown discount, as he was committed to ensuring that the team would stay put.44

The 1980 squad was, in a word, loaded. In addition to Bass and future big-league catcher Steve Lake, they possessed a pitching staff that featured MLB mainstays Doug Jones, Frank DiPino, and Chuck Porter. Rick Kranitz led the team with 13 wins, while closer Kunikazu Ogawa saved 16 games with an earned run average of 1.96.45

The featured attraction at MacKenzie that summer, however, was David Green — a prospect who had been dubbed “the next Roberto Clemente.”46 Green was the son of Edward Green Sinclair, considered one of the best Nicaraguan players of all time. The younger Green was a five-tool prospect, leading the Eastern League in triples with 19 while batting .291 and earning a spot on the Eastern League All-Star Team.47

Manager Lee Sigman’s squad ran away with the Northern Division, finishing with a record of 78–61, a full ten games ahead of their closest competitors. They rolled into the playoffs against the Buffalo Bisons, with Green blasting the winning home run off Dave Dravecky in the clinching game to put Holyoke into the Eastern League Finals against the Waterbury Reds.48

In the finals, the Millers dropped the opener by a count of 3–2, but bounced back in Game Two behind a combined six-hit shutout by Kranitz and Ogawa to even the series.49 In the winner-take-all Game Three, Doug Loman homered, tripled, and doubled while Chuck Porter threw a complete-game shutout as the Millers defeated the Reds, 7–0, to claim the 1980 Eastern League Championship before 2,717 fans.50 It was a glorious night in Holyoke, as children danced on top of the Millers dugout to “We Are Family,” the Sister Sledge classic that had become the unofficial anthem of the Pittsburgh Pirates during the previous summer. It would be the first professional baseball title for a Western Massachusetts team since the Springfield Giants won the Eastern League for three consecutive seasons 1959–61. The Giants of those championship years featured a number of future legends, including Manny Mota, Matty Alou, and Juan Marichal.51

The Millers had their heyday under owner-GM Tom Kayser, who ended up selling the team to take a position in the Pittsburgh Pirates organization, and later became president of the Texas League. (Image: TCMA)

The 1980 season of the Millers would prove to be the franchise’s high-water mark. On December 12, 1980, the parent Brewers pulled off a blockbuster trade with the St. Louis Cardinals, trading David Green along with Sixto Lezcano, Lary Sorenson, and Dave LaPoint in return for future Hall of Famers Rollie Fingers and Ted Simmons, along with future ace (and Major League actor) Pete Vukovich.52 Milwaukee also moved on from their affiliation with Holyoke, establishing their AA team in El Paso. The Brewers organization wanted out of the Eastern League — as the cold northeastern weather, sub-par ballparks around the league at the time, and the cinder track that ran through the outfield at MacKenzie Field were all factors leading to their departure.53 The California Angels would fill the void left by Milwaukee — and although the new-look Millers would feature a number of future major leaguers, this would not translate to on-field success in 1981 or 1982.

In 1981, Holyoke rode the coattails of their championship season at the turnstiles, as they drew an all-time franchise high of 80,117. While the team got off to a strong start, they would end up faltering down the stretch, finishing a whopping 16½ games behind the first place Glens Falls White Sox.54

Speed was the name of the game for the Millers in ‘81, as future Angels mainstay Gary Pettis’s 55 stolen bases would pace a team that would swipe a total of 151. Darrell Miller wore his last name on both the front and back of his jersey, splitting time between catcher and outfield — long before his two siblings Reggie and Cheryl would both be inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame just down the road in Springfield. Dennis Rasmussen posted a record of 8–12, while showing flashes of potential he would later fulfill in the majors — all while living in what he believed was an illegal trailer park at the foot of Mount Tom.55

The biggest news around the Millers in 1981 would occur in early November, when team owner Tom Kayser announced he was offered a position as the Assistant Minor League Director for the Pittsburgh Pirates organization, and would be selling the team.56 It ended up being a wise career move for Kayser, who would ultimately spend 25 years as the president of the Texas League, retiring in 2017.

A Holyoke-based group of executives led by City Alderman Hal Haberman were the early favorites to purchase the team, with an Eastern Massachusettsbased group also solidly jockeying for position.57 In total, more than 30 potential bidders from as far away as Florida and California made inquiries about buying the team, before a different local group made a deal to purchase the Millers to keep them in Holyoke.

University of Massachusetts Political Science Professor Jerome Mileur recalled “having a few beers at the White Eagle Club” in Amherst with fellow UMass employee George Como (a systems analyst in the computer center) when they floated out the idea of purchasing the team from Kayser.58 They recruited local heating oil businessman Ben Surner, and ultimately put in a bid of $85,000 to buy the Millers. The deal was announced on December 1, 1981.59

Unfortunately, the new ownership team stumbled early out of the blocks. The ownership group’s first hire was general manager Larry Simmons, who would not make it to opening day before being fired.60 the Eastern League establishment was cautious of the new ownership group, with longtime owner Joe Buzas directly asking Mileur at the Winter Meetings, “Why the hell would a college professor want to own a baseball team?” Mileur simply responded that he was a great fan of the game and had best of intentions.61

The team itself also struggled, as the Angels prospects failed to make an impact with the local fans, with attendance plummeting to just over 54,000. Oddly, the highlight of the season was not one that was readily apparent, as young author Domenic Stansberry had moved to Holyoke and was writing a murder mystery based on the Millers and Holyoke called The Spoiler. While Stansberry has had a moderately successful career in the interim, The Spoiler has remained out of print for many years, an apt analogy for the fate of the Millers.62

However, the biggest challenge the group would face was their rocky relationship with city officials. MacKenzie Field also doubled as the home baseball diamond for two of the high schools in the city, and there was increasing pressure from members of the community to ensure that their municipal field would be utilized by residents. Ultimately, it was decided that the Millers would not have access to the field for practice during the school year, as the teams from Holyoke High School and Holyoke Catholic High would be given priority. Additionally, the cinder running track that ran through the outfield would also be utilized by the track teams at these schools before the Millers.63

Public meetings between Millers owner Surner and Holyoke Mayor Ernest Proulx would become increasingly more contentious, and the team and city reached an impasse that could not be overcome.64 The Millers would move to Nashua, New Hampshire and participate in the 1983 Eastern League season as the Nashua Angels.65

Coincidentally, one of the factors the ownership group faced in Nashua was a boycott from the community, who felt that the presence of the team was having a negative impact on attendance at youth baseball games. After four years in Nashua, Mileur had bought out both Surner and Como and the team was moved to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where the franchise has had a long and successful tenure. Mileur would ultimately retire from ownership in 1994, selling the team to the City of Harrisburg for four million dollars.66

While the Nashua Angels returned to play a single game at MacKenzie Field during the summer of 1983, it would be the end of professional baseball in Holyoke. Currently, the Valley Blue Sox of the New England Collegiate Baseball League play their home games at MacKenzie every summer. It seems hard to believe that Holyoke — given its lack of professional-level facilities — was able to be home to a AA team, even if only for six years. Clearly, the economics and atmosphere around minor league baseball have shifted so radically over the years that such a scenario would be impossible today — and it was honestly quite miraculous that it was able to happen then.

ERIC T. POULIN is an Assistant Professor of Library and Information Science at Simmons University, where he directs their Western Massachusetts-based campus. He first joined SABR in 2002 after completing a Steele Internship at the A. Bartlett Giamatti Center for Research at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. This is his first contribution to the Baseball Research Journal.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the late Jerome Mileur for his insight, along with Ben and Jay Demerath III for making invaluable connections. Eileen Crosby and the staff at the Holyoke History Room were incredibly gracious with their time, as well as the great Tim Wiles and the A. Bartlett Giamatti Center for Research at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Tom Kayser was very generous with his insight and information. Maury Abrams and Pumpkin Waffles provided tremendous support and perspective. Above all, eternal gratitude goes to Gabriela Stevenson for her editing, fact-checking, and overall determination to ensure the story of the Millers would be told.

Notes

1. Ella Merkel DiCarlo, Holyoke — Chicopee: A Perspective, Holyoke, MA: Transcript-Telegram, 1982.

2. Merkel DiCarlo.

3. Merkel DiCarlo.

4. Merkel DiCarlo.

5. Merkel DiCarlo.

6. Merkel DiCarlo.

7. Merkel DiCarlo.

8. Merkel DiCarlo.

9. Merkel DiCarlo.

10. Merkel DiCarlo.

11. Merkel DiCarlo.

12. Bill Doyle, “Eastern League President Favors Holyoke for Franchise,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, December 3, 1976.

13. “City Needs Money For EL Team,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, October 15, 1976.

14. “City Needs Money For EL Team.”

15. Milton Richman, “Gate-Slim Pittsfield Boss On Hunger Strike,” The Sporting News, July 10, 1971, 43.

16. “Aldermen Welcome Franchise,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, December 22, 1976.

17. Michael J. Burke, “Special Arson Squad Makes First Arrest,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, April 13, 1977.

18. “Miller Hitters Maul Minutemen Hurlers,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, April 14, 1977.

19. “G.E. Eliminating 225 Jobs,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, April 13, 1977.

20. Bill Doyle, “Millers’ Debut Is a Success,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, April 26, 1977.

21. Doyle.

22. “Blessitt Is Most Popular,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, September 6, 1977.

23. Milton Richman, “Blessed Are the Peacemakers? Ask Martin,” The Sporting News, March 29, 1973.

24. Richman, “Blessed Are the Peacemakers…”

25. Phil Pepe, “Yanks Wheel, Deal, and Squeal,” The Sporting News, September 19, 1979.

26. Lee Thompson. “Former Detroit Tigers Outfielder Ike Blessitt Bringing His Big-League Story to Bay City for Bay Medical Charity Auction,” Mlive, April 28, 2011, accessed August 31, 2021. https://www.mlive.com/sports/baycity/2011/04/former_detroit_tigers_outfield.html.

27. “Nothing Is Working for Failing Millers,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, May 4, 1977.

28. “‘Guaranteed Win Day’ Starts Millers’ Promotions,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, May 6, 1977.

29. Bill Doyle, “Millers ‘Shave’ Bristol Sox, 8–7,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, May 18, 1977.

30. “‘Guaranteed Win Day’ Starts Millers’ Promotions.”

31. Bill Doyle, “Millers Clinch Third Place,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, September 3, 1977.

32. Bill Doyle, “Miller Players Are Ready to Bid Holyoke Farewell,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, September 2, 1977.

33. Michael Burke, “Fire Destroys Main St. Block,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, May 28, 1977.

34. Bill Zajic, “Hannon ‘Curves’ Giants,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, May 3, 1978.

35. Bill Doyle, “Millers Pitching Collapses in Loss,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, May 8, 1978.

36. The Baseball Cube, accessed August 31, 2021. http://www.thebaseballcube.com/minors/teams/stats.asp?Y=1978&T=10573.

37. Ray Fitzgerald, “His Vision on Target,” Boston Globe, July 7, 1981.

38. Mike Downey, “Would Fans Respond to ‘Bark Like a Dog’?” The Sporting News, October 27, 1986.

39. “Religious Millers,” The Sporting News, August 11, 1979, 44.

40. “Religious Millers.”

41. Pat Cahill, “Holyoke Mall Celebrates Its 10th Anniversary,” Sunday Republican. July 16, 1989.

42. Cahill.

43. Garry Brown, “Want To Buy a Ball Club?” Sunday Republican. May 11, 1980.

44. Brown.

45. The Baseball Cube, accessed August 31, 2021. http://www.thebaseballcube.com/minors/teams/stats.asp?Y=1980&T=10573.

46. John Sonderegger, “Potential: The One Thing a Gimed David Green Couldn’t Grasp,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 14, 1986.

47. Bill Doyle, “Holyoke Proves Itself,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, September 6, 1980.

48. Warner Hessler, “Millers End Bisons’ Year,” Buffalo Courier-Express, September 1, 1980.

49. Bill Doyle, “Millers Force Showdown,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, September 3, 1980.

50. Mike Bogen, “Millers Cop EL Crown,” The Morning Union, September 6, 1980.

51. Garry Brown, “Springfield Marks 50 Years without a Professional Baseball Team; Is It Time to Take Another Swing?” MassLive, March 22, 2015, accessed August 31, 2021. https://www.masslive.com/living/2015/03/garry_brown_springfield_marks_50_years_without_a_professional_baseball_team.html.

52. Sonderegger.

53. “It’s Spring Again,” Hampden County Enterprise, April 13, 1981.

54. The Baseball Cube, accessed August 31, 2021. http://www.thebaseballcube.com/minors/teams/stats.asp?Y=1981&T=10573.

55. Owen Canfield, “Remembering the Eastern League,” The Sporting News, May 9, 1985.

56. Barry Schatz, “Millers owner bows out; local businessmen want to buy team franchise,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, November 5, 1981.

57. Schatz.

58. Author interview with Jerome Mileur, October 19, 2006.

59. Barry Schatz, “Millers’ Deal to Keep Team in Holyoke,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, December 2, 1981.

60. Don Conkey, “The Holyoke Millers: Sharp Decline in Attendance Just One of Many Problems Confronting New Management,” The Sunday Republican, May 23, 1982.

61. Author interview with Jerome Mileur, October 19, 2006.

62. Domenic Stansberry, The Spoiler: A Novel, New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1987.

63. Barry Schatz, “Field Availability Is Snag between City, Millers,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, October 14, 1982.

64. “Proulx Says Millers Should Be More Flexible,” Holyoke Transcript-Telegram, October 22, 1982.

65. Milton Cole, “Nashua Votes to Take Millers,” Daily Hampshire Gazette, December 7, 1982.

66. Author interview with Jerome Mileur, October 19, 2006.