The Hearst Sandlot Classic: More than a Doorway to the Big Leagues

This article was written by Alan Cohen

This article was published in Fall 2013 Baseball Research Journal

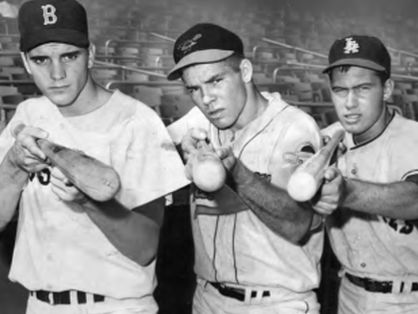

U.S. All-Star outfield from the 1962 game have their bats locked and loaded. The players are (L–R) Tony Conigliaro, Ron Swoboda, and James Huenemeier. Conigliaro and Swoboda starred for the Red Sox and Mets, respectively. Huenemeier signed with the White Sox, but never got beyond Class A. (HARRY RANSOM CENTER/JOURNAL-AMERICAN ARCHIVES)

Set against the backdrop of a country emerging from war, and entering into a period of prosperity, the Hearst Sandlot Classic, over 20 years offered a showcase for young baseball talent. Many of those who participated signed professional contracts and others were able to obtain scholarships to further their education. Everyone who participated gained memories to last a lifetime.

In 1946, sportswriter Max Kase of the New York Journal-American was instrumental in creating the Hearst Sandlot Classic. The game featured the New York All-Stars against the U.S. All-Stars. The annual event was held at the Polo Grounds in New York through 1958, and was moved to Yankee Stadium in 1959. The program had the backing of media magnate William Randolph Hearst who, early on, stressed the goals of the program. “This program will be conducted in all Hearst cities from coast to coast. The purpose of the program will not be to develop players for organized baseball, but will be designed to further the spirit of athletic competition among the youth of America.”1

Of the young men who appeared in the games, 89 advanced to the major leagues, but the story is incomplete without a mention of those behind the game, and those whose lives were touched by the experience. From Hall of Famers to those whose careers consisted of the proverbial cup of coffee, to those who gained success outside of organized baseball—it all started when they were young.

Getting into the game was no easy task. Hearst Newspapers throughout the country sponsored tournaments, All-Star contests, and elections to determine candidates for the game in New York. Newspapers that sponsored events included the Milwaukee Sentinel, Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, San Francisco Examiner, Los Angeles Herald-Express, Baltimore News-Post, Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Detroit Times, Albany Times-Union, Chicago Herald-American, and the Oakland Tribune.2

The New York team was selected from tryouts held in the leagues that comprised the Journal-American City Sandlot Alliance. Hall-of-Famer Walter James Vincent “Rabbit” Maranville headed up the program and managed the New York team.

Maranville was truly one of the game’s legends. He began his major league career in 1912 with the Boston Braves and played in the majors for 23 years. He arranged clinics for youngsters in the New York area under the tutelage of players, coaches, and managers from the three New York major league squads. In the weeks leading up to the 1946 event, he contributed a daily column in the Journal-American extolling the talents of his 20-man roster. Although sentiment did play a role in his election to the Hall of Fame in 1954, (he had died just prior to the voting), his work with the youth program and his stellar fielding during 23 major league seasons were also significant factors.

George Vecsey of The New York Times stated, in 1989, that Maranville’s two greatest attributes were longevity and good deeds as the sandlot ambassador for a newspaper chain with many Hall of Fame Electors.3

An exceptional middle infielder, Maranville still holds the career record for assists with 8,967. As his career wound down, his fielding skills were as good as ever. In 1930, at the age of 38, he led the league’s shortstops in fielding percentage and two years later he moved to second base and duplicated the feat. Not noted for his batting, he nevertheless ranks 19th all-time with 177 triples.

Arthur Daley of The New York Times was an ardent supporter of Maranville, voting for him on several occasions before he gained entrance to the Hall of Fame. Maranville had been named on 62.1% of the ballots in 1953. Noting Maranville’s off-the-field escapades (he definitely enjoyed a good time), Daley stated that “there was a certain amount of irony in the fact that the Rabbit’s later years were spent in doing an extraordinarily fine job in promoting sandlot baseball for the Journal-American. He was helping and inspiring the kids, although he would have shuddered in horror if any of them had ever followed his (off-the-field) example. But maybe there was not so much irony in his job at that. The Rabbit was always a kid himself, a Peter Pan who didn’t want to grow up.”4

The Rabbit managed the New York team for the first eight years of the event. Al Simmons took over in 1954. Simmons, a Hall-of-Famer, got his start playing sandlot ball in Milwaukee as a youngster, and managed in the Classic for two years until his untimely death in 1956.5 George Stirnweiss took over in 1956 and Tommy Holmes in 1959.

Ray Schalk and Oscar Vitt led the U.S. All-Stars. Schalk managed the team through 1948. He stepped aside after three years, as his contract as baseball coach at Purdue did not allow him to engage in any outside activities. At the time he left, he said that he “liked being around the kids and the biggest kid of all, Rabbit Maranville.”6 Vitt took over the head job, ably assisted by such greats as Charlie Gehringer and Lefty Gomez, and stayed with the program until illness forced him to step aside in 1962. Vitt was a veteran of the game. He played with the Detroit Tigers from 1912 through 1918, and the Red Sox from 1919 through 1921. He managed the Cleveland Indians from 1938 through 1940. He retired in 1942 after a two-year stint in the Pacific Coast League, and became headmaster at a school near San Rafael, California.

The Brooklyn Eagle competed with the Journal-American and got into the act with its “Brooklyn Against the World” games at Ebbets Field from 1946 through 1950. The main forces behind the game were Branch Rickey of the Dodgers and Lou Niss, the sports editor of the Eagle. One player for the 1946 “World” team was sent east by the Los Angeles Times. Vic Marasco had the time of his life. “Those people from the Brooklyn Eagle and the Brooklyn Dodgers didn’t spare the horses when it came to taking us around.” He summed it all up by saying “I think I learned more on this trip than all the time I was in Fremont High and I just want to congratulate the kid who makes it next year. He’s in for the biggest treat of his life.”7 Marasco signed with Brooklyn and spent 10 seasons in the minor leagues, putting up some pretty good numbers. But Triple A was as far as he would get.

Brooklyn Against the World contests had top flight managers. In 1946 the Brooklyn team was managed by Leo Durocher and the World team by Hall of Famer George Sisler. It was a three-game series, played August 7–9. Playing right field in the second game was Ed Ford of Astoria, Queens and Aviation High School. It was his only appearance in the series. His natural position was pitcher, but others were lined up ahead of him in 1946. Prior to the first game of the series, Brooklyn legend Gladys Gooding performed the National Anthem.8

Durocher used six pitchers during the three games. Several signed on to contracts with big league teams, but none made it to the majors. Ed Fordsigned with the Yankees. Along the line, he became known as “Whitey” Ford and had a Hall-of-Fame career with the Bronx Bombers.

The inaugural Hearst game was played on August 15, and set the bar as to the visitors having a lifetime memory. A trip around Manhattan Island by boat, a Broadway show—that year it was “Showboat,” a trip to West Point, dinner at the Bear Mountain Inn, accommodations at the Hotel New Yorker, and an opportunity to perform in front of major league scouts and meet with major league players. Nine players from the inaugural teams went on to play in the big leagues. The game was won 8–7 in eleven innings by the New Yorkers in front of 15,269 fans.

Umpiring that first game was the dean of umpires and reigning National League Umpire-in-Chief, Hall of Famer Bill Klem. He was assisted by Butch Henline and Dolly Stark. Klem and Henline had also, along with Jim Druggoole, umpired the inaugural Brooklyn Against the World games earlier in August.

Billy Harrell, who appeared in the 1947 game, holds the distinction of being the first player of color to appear in the Hearst Classic and make it to the majors. Harrell grew up in Troy, New York, and after playing in the Classic, attended Siena College, where he also played basketball. He signed with the Indians in 1952. He played with the Tribe in 1955, 1957, and 1958, and finished up his major league career with Boston in 1961. Harrell’s appearance was even more historical in that, when he played in the Hearst Classic for the first time, Major League Baseball was not integrated. In light of Harrell’s appearance, heavyweight champion Joe Lewis bought 1,000 tickets for the game, and these tickets were distributed by The Amsterdam News to children in Harlem.9

The MVP of the very first game was Dimitrios Speros “Jim” Baxes of San Francisco, who could easily be mistaken for Joe DiMaggio, to whom he bore an uncanny physical resemblance. Not only did he come from the same city as the Yankee Clipper, but he also adopted Joe’s batting style.10 He tore things up in the Classic, going 3-for-6 with a double, and contributing to the three rallies that generated all of his team’s runs. Baxes was signed by the Dodgers in 1947, and made it to the majors in 1959. That would be his only major league season. He got into 11 games with the LA Dodgers before being traded to Cleveland. In 280 major league at bats he batted .246 with 17 homers and 39 runs batted in.

Of the players in the 1946 Hearst Classic who made it to the majors, the best success was enjoyed by Billy Loes. Loes was signed by the Dodgers prior to the 1949 season for a bonus estimated at $22,000. Under the bonus rule in effect at the time, Loes could spend one year in the minors, after which he had to be placed on the major league roster or exposed to the Rule 5 draft. He split the 1949 season between Class B Nashua (NH) and Class AA Fort Worth, posting a 16–5 record. In 1950, with the Dodgers, he saw very little activity, getting into 10 games and pitching a total of 122⁄3 innings. After a year in the military, he returned to Brooklyn and posted a 50–25 record over the next four seasons.

Earl Smith signed with the Pirates in 1949, but found himself stuck in their minor league system for far too long. In 1955, he finally got to the big club and wore number 21 for five games, garnering one hit in 16 at-bats. On April 29 he played his last game, and number 21 was reassigned for the last time—to Roberto Clemente.

The career of Paul Schramka was even shorter. He signed with the Cubs in 1949. After a good spring training in 1953, he started the season with the big club assigned uniform number 14. He got into two games, one as a pinch runner and the other as a defensive replacement. He never came to the plate. His last game was on April 16, 1953. A few days later, he was sent to the minors and number 14 was reassigned for the last time—to Ernie Banks.

The Class of 1947 produced the most major leaguers—10 in all—in the history of the Hearst Classic. Playing for the U.S. team, which won a lopsided 13–2 decision, were three men who would be reunited in the 1960 World Series: Gino Cimoli, Dick Groat, and Bill Skowron. An all-time record 31,232 fans attended the game which featured a Golf and Baseball exhibition by Babe Didrikson Zaharias and a performance by the Clown Prince of Baseball, Al Schacht. The icing on the cake was one of the last appearances by the game’s honorary chairman, Babe Ruth.

Harry Agganis, who made it to the majors with the Red Sox in 1954–55, represented Boston on the 1947 U.S. team, and signed with the Red Sox organization in 1952 after completing his studies at Boston University. He was en route to the most promising of careers, batting .313 in his second major league season, when he was hospitalized with what was diagnosed as a massive pulmonary embolism. He died six weeks later at the age of 26.

One of the New York pitchers on the short end of the thrashing was Bob Grim, who went on to success with the Yankees, winning the Rookie of the Year Award in 1954 with a 20–6 record.

The center fielder for the U.S. team in 1947 was only 15 years old at the time and still in high school. Billy Hoeft signed with Detroit in 1950 as a pitcher, and two years later made his debut with the Tigers. In 1955 he went 16–7 with a 2.99 ERA and was named to the All-Star team. The following year, he went 20–14 for his only 20-win season.

At Ebbets Field, San Francisco’s Gus Triandos caught in Brooklyn Against the World. He was signed by the Yankees and saw limited experience with the Bombers during the 1953 and 1954 seasons. Prior to the 1955 season, he was part of a deal with Baltimore involving 17 players. He spent eight years with Baltimore, banged 142 homers, and was named to four All-Star teams.

Baseball lost Babe Ruth on August 16, 1948, and the 1948 Hearst game was played in his memory. One tribute featured Al Schacht doing his pantomime of the Babe’s called shot in the third game of the 1932 World Series, and Robert Merrill brought tears to everyone’s eyes with his rendition of “My Buddy.”11 The tributes were many. Also on hand was Johnny Sylvester, who was eleven years old when the Babe made his fabled hospital visit in 1926—a visit which was said to have saved the young man’s life.12 To the end, The Babe was devoted to his young fans, and on his deathbed, made provisions in his will that 10 percent of this estate was bequeathed “to the interests of the kids of America.”13

Tom Morgan represented Los Angeles, started in centerfield for the U.S. All Stars, and went 2-for-3. After the game, he made a decision. “Right then and there I decided I had to play in New York, if I ever could prove myself good enough and that I had to do it as a Yankee. So when I got back home, I didn’t waste any time fooling. Five or six other scouts had been talking to my folks about me, but I signed right up with Joe Devine of the Yankees.”14 He signed in the spring of 1949, and went 29–17 during his first two minor league seasons. That earned him a rapid promotion to the majors and he went 9–3 for the 1951 World Champions. He stayed with the Yanks through 1956 and spent the next seven seasons with four different American League clubs. He finished up with the Angels in 1963. For his career, he went 67–47.

The 1948 U.S. squad included a player who became the first round draft pick of the Mets in the expansion draft after the 1961 season: Hobie Landrith. Landrith was one of seven catchers to play for the Mets in 1962. Early in the season, he was the “player to be named later” when the Mets traded him to Baltimore for Marv Throneberry.

Mike Baxes, Jim’s brother, ventured to the game from San Francisco’s Mission High School, and signed with the Phoenix Senators of the Class C Arizona-Texas League in 1949. By 1951 he was playing at Class B Yakima where he batted .318 with 37 doubles. Eventually he was traded to the Kansas City Athletics and made his major league debut in 1956. In parts of two major league seasons, he got into 146 games and batted .217.

Brooklyn Against the World took on a new look in 1948. After hosting a team from Washington, D.C., the Brooklyn forces hit the road for games in Washington, Montreal, Toronto, Providence, and Halifax, Nova Scotia. The Brooklyn aggregation was led by Billy Loes, who won two games during the trip and signed with the Dodgers after completing the trip.15

Loes was one of two players to play in both the Hearst game and Brooklyn Against the World and make it to the majors. Chris Kitsos of Brooklyn’s James Madison High School was the other. He appeared in both games in the inaugural year of 1946, signed with the Dodgers and spent five seasons in their minor league system before being drafted by the Chicago Cubs after the 1951 season. The Cubs called the shortstop up in 1954, and on April 21, he was inserted as a defensive replacement in the eighth inning. He handled two ground balls flawlessly, returned to the dugout, and never re-emerged. His major league career was over.

Loes’s battery mate in the 1948 BAW series also was signed by the Dodgers, but did not perform particularly well behind the plate in limited activity at his first minor league stops. In fact, the Dodgers released him. But he persevered, worked on his fielding with the help of George Sisler, and returned to the Dodger organization.16 After eight minor league stops and a two year stint in the military, Joe Pignatano played eight games for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1957. He played all nine innings on September 29, 1957, in the last game played by the Brooklyn Dodgers. His major league career lasted through 1962 when he finished with the Mets. After a short trip back in the minors, he coached for twenty years with the Senators, Mets, and Braves.

In its final two years, 1949 and 1950, “Brooklyn Against the World” was scaled down, and it became a home and home series between the Brooklyn lads and a team representing Montreal, Canada. In 1949, the first game was played in Brooklyn on July 26 and won 9–7 by Montreal in eleven innings. The next game, in Montreal, was won by Brooklyn. In 1950, Brooklyn swept the two games by 10–4 and 11–1 margins.

Both the winning and losing pitchers in the 1949 Hearst game advanced to the majors. Representing Seattle in the 1949 game was a tall kid from Richland, Washington. He had just completed his freshman year at Washington State College. In the 1949 game, he entered the game in the fourth inning, and in three innings, allowed no hits, struck out six, and was credited with the win as the U.S. All Stars came back from a 0–5 deficit to defeat the New York squad 7–6.17 At WSC, he excelled in both baseball and basketball.

Gene Conley left WSC after two years and was signed by the Boston Braves. After going 20–9 at Hartford in 1951, he began the 1952 season with the Braves in Boston, but had limited success until the team moved to Milwaukee. In his first two years in Milwaukee, he went 25–16 and was named to two All-Star teams. His major league career ended with the Red Sox in 1963.

New York’s losing pitcher also signed with the Braves prior to the 1951 season. Frank Torre signed as a first baseman. He played, along with Conley, on the Braves pennant winners in 1957–58, and hit .300 as the Braves defeated the Yankees in the 1957 World Series. Torre shared first base duties with Joe Adcock through 1960.

In 1950 Pittsburgh’s representative played first base in the Hearst Classic. The Pirates signed him to a contract and Tony Bartirome was in the majors two years later, playing 124 games for the last-place Bucs. It would be his only major league season. After the season, he was drafted and spent two years in the Army. When he returned, he played in the minors and then spent 22 years as a trainer, 19 of them as head trainer for the Pirates from 1967 through 1985.

The 1951 game included Jersey Joe Walcott giving a two-round boxing exhibition as part of the pre-game festivities. Not only did Walcott appear, but he donated $500 to the cause after winning the money on a television quiz show, “Break the Bank.” His donation was matched by Yankee great Phil Rizzuto, and Walcott, himself, purchased 1,000 tickets to the game, to be used by area youngsters.18

John “Tito” Francona, who represented New Brighton High School and Pittsburgh, signed with the St. Louis Browns and went on to play 15 years in the big leagues.

That was quite modest compared to the fellow who was the MVP in the Hearst Classic that year. He hailed from Baltimore and had just completed his sophomore year of high school. His performance came as no surprise. As a high school freshman, he had been named to the All-State team. He went 2-for-4 in the Hearst Classic with a double and an inside-the-park homer that sailed over the center fielder’s head. In the field, he was equally adept, making five good plays and gunning down a runner at third base. He signed for a bonus when he completed high school in 1953 and, due to the bonus rule in effect at the time, went straight to the Tigers. Al Kaline played 22 years with the Tigers and was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1980.

Kaline was one of five Hearst alumni to sign for bonuses and go directly to the major leagues. His success far exceeded that of the four other “Bonus Babies” who had played in the Hearst game.

Although many kids who signed for bonuses during this time were given hostile receptions, Kaline was embraced by his teammates and the Tiger organization. It was obvious that he was a superlative fielder, and his hitting came around. Fate intervened and gave Kaline his big chance. An off-season injury to regular right fielder Steve Souchock kept him out of the lineup and Kaline was the only right fielder left. The Tigers were going no place and manager Fred Hutchinson played Kaline. As Don Lund said, “Although he started slowly, he gained confidence, enhanced his skills, and finished with a fine year. Al used the bonus rule to his advantage and had a minor league experience in the major leagues. The rest is history.”19

Milwaukee was represented, in 1952, by a shortstop whose father had played some minor league ball. He did not sign right away, as he was only 16 when the game was played in 1952. One of his highlights was having his picture taken with Yogi Berra.20 It wouldn’t be the last time. He went back to high school in Wisconsin and signed with the New York Yankees in 1954. Tony Kubek made his debut with the Yankees in 1957 and spent nine years in the Bronx. He was named American League Rookie of the Year in 1957, was named to All-Star teams in 1958, 1959, and 1961, and played in two All-Star games. He pinch hit in 1959 and started the first game in 1961.

The bonus rule of 1953 attached a player signing for a bonus and salary in excess of $4,000 to the major league team for two years. There were four Hearst players signed in 1953 who were tied to their teams. The experience did not prove beneficial to most of the young men involved.

One such player came from Holyoke, Massachusetts, and represented Boston in the 1953 Classic. A scholar-athlete, he stood 6’4″ and weighed 210 pounds. As a high school senior, Frank Leja hit safely in each of his team’s 21 games and batted .432. After graduating, he was courted by several teams. The Giants, Braves, and Indians were cited for tampering.

Eventually, he signed with the Yankees for an estimated $60,000. For two years, Leja sat on the bench. He got into only 19 games, and had one hit in seven at-bats. He spent the next six seasons in the minors and returned to the majors with the Angels for a brief stay in 1962, going hitless in 16 at-bats. At the time of his death, his age (55) was higher than his career batting average (.043).

Leja’s feeling was that he had never gotten a fair shot. His first season with the Yankees was 1954. It was the only time in a 10-year span that they did not win the American League pennant and the players felt that his presence on the roster denied an opportunity to a player stuck in the minors. Manager Casey Stengel, with the pennant on the line, was not about to play an unproven talent. So Leja sat.21

The 1954 game was played in some chilly weather in front of 9,143 spectators and Bill Monbouquette, representing Boston, won MVP honors, as the U.S. team won 5–3. Monbo, celebrating his 18th birthday, struck out five of the six batters he faced, and went on to a successful career with the Red Sox.

Barry Latman, from Los Angeles, was signed by the White Sox. He pitched 11 years in the majors and compiled a 59–68 record. He went 8–5 for the 1959 White Sox when they won the American League pennant, and was named to the All-Star team when he went 13–5 for Cleveland in 1961.

Fred Van Dusen is not known by many fans of the game. He played first base for the New York Stars in the 1954 game and went 0-for-2. At the tender age of 18, he was signed by the Phillies on August 20, 1955, and made his major league debut on September 11, 1955. At Milwaukee, he came up as a pinch hitter in the top of the ninth with one out and the Phillies trailing the Braves by a 9–1 count. In his only major league appearance, he was hit by a pitch.

Gary Bell was the first San Antonio player to make it all the way to the big leagues. He was signed by the Cleveland Indians and made it to the majors in 1958. Over the course of twelve major league seasons, he pitched to a 121–117 record and was named to four All-Star teams.

One of the participants on the New York squad in 1955 was Herman Davis. This fellow could hit and was snapped up by the Brooklyn Dodgers, but never got to play in Brooklyn. By the time he was ready for the big leagues, the Dodgers were in Los Angeles, and Tommy Davis made his first big league appearance on September 22, 1959. He went on to win batting championships in 1962 and 1963, and was selected to the National League All-Star team in each of those years. A knee injury in 1965 set him back, but he reemerged as a designated hitter in the 1970s with Baltimore. Over the course of his 18-year career, he batted .294 and amassed 2,121 base hits.

The California player of the year was named the MVP of the 1956 Hearst game, pitching the last two innings and striking out each of the six batters he faced. Mike McCormick signed for a bonus of $65,000 with the Giants. Since the bonus rule was still in effect, he went directly from the Polo Grounds to the Polo Grounds.22 During his first two years with the Giants, he had only seven starts, but saw more action when the team moved to San Francisco. He led the National League with a 2.70 ERA in 1960, and was named to the All-Star teams in 1960 and 1961. After the 1962 season, he was traded to Baltimore and then Washington before returning to the Giants in 1967 for his best year ever. He went 22–10 with a 2.85 ERA and was selected as the National League Cy Young Award winner. His 134–128 major league career ended in 1971.

McCormick was accepted well by his Giant teammates when he joined the club at the end of the 1956 season. However, the youngster did combat loneliness in the early days. He remembers that “I really valued my time at the ballpark, because that was the only time I was able to feel like I was part of something. When the game ended, because of the age discrepancy, guys would go drinking or something, and I didn’t know what alcohol was. This was on the road. Then at home they had families, so I spent an inordinate amount of time by myself. I ate by myself, went to a lot of movies, just did things to keep busy, looking forward to going to the park.”23

The other Los Angeles representative in 1956 went back to college after competing in the Hearst Classic. After two years at USC, Ron Fairly signed with the Dodgers for $75,000. Since the bonus rule was no longer in effect, he was sent to the minors for a brief spell before coming up to the Dodgers late in the 1958 season. He batted .238 in 1959 and spent most of 1960 at Triple A Spokane, batting .303. Fairly was up to stay in 1961. Over the course of his 20-year career, he batted .266 with 1,913 hits, and was named to two All-Star teams.

San Antonio had been sending players to the Hearst Classic for 10 years with only Gary Bell making the big time. Their 1956 representative would change that. Joe Horlen attended Oklahoma State University before signing with the White Sox in 1959. He made it to the show in 1961 and spent 12 years in the majors, 11 with the White Sox. His best season was 1967 when he went 19–7, led the league with a 2.06 ERA, and finished second in the Cy Young balloting.

The 1958 game featured two players who would make it to the major leagues in a very big way. Ron Santo, the starting catcher for the U.S. team, signed with the Cubs, was converted to third base in his Texas League days, and had a Hall-of-Fame career in the Windy City. Joe Torre, who started the game on the bench for the New York team, went on to stardom with the Braves and Cardinals, and managed the New York Yankees to six pennants and four World Championships.

Of those players from the 1959 game who made it to the majors, pitcher Wilbur Wood and infielder Glenn Beckert were named to All-Star teams during the course of their careers.

The U.S. Stars won the 1960 game 6–5. The pitcher who closed the deal had entered the game in the sixth inning to play right field, and went to the mound in the bottom of the eighth to pitch the last four outs. It wouldn’t be the last time he finished up a game in relief. He was with his fourth major league team, the Montreal Expos, when he achieved success. Mike Marshall was moved permanently to the bullpen and saved 23 games in 1971. In four seasons in Montreal, he saved 75 games and posted a 2.94 ERA. Then it was on to Los Angeles and a share of immortality. In 1974, he appeared in 106 games, posted a 2.42 ERA, was credited with 21 saves, made the All-Star team, and won the National League Cy Young Award.

The starting catcher for the U.S. Stars represented Detroit. Bill Freehan was signed by the Tigers prior to the 1961 season and saw action in Detroit as a late season call-up. After a solid 1962 at Denver in the American Association, Freehan returned to Detroit to stay in 1963. In 14 full seasons with the Tigers, he was named to 11 All-Star teams, including 10 in succession from 1964 through 1973. He was also awarded five consecutive Gold Gloves (1965–69).

The 1961 game produced still more future major leaguers. The most notable pair represented San Antonio.

The second baseman was actually a catcher. He signed with Houston in 1962. In two years with the Colt 45’s, he batted only .182. He was sent back to the minors and, after the 1965 season, was traded to the New York Mets. Jerry Grote appeared in his first game with the Mets on April 15, 1966, and went on to play 12 seasons in Queens. He was named to two All-Star teams, and has a rightful place in the Mets Hall of Fame.

The shortstop switched to second base and signed with the Baltimore Orioles in 1962. He was very highly thought of by assistant manager Buddy Hassett who commented, “I like his wrist action and the way he whips the bat around so fast.” Two long homers, one of which sailed to the upper deck at the Bronx ballpark, were particularly impressive.24 He signed with Baltimore and joined the Orioles in 1965. During the course of his playing career Davey Johnson was named to four All-Star teams and won three Gold Glove Awards. After his playing days, he managed the Mets to the 1986 World Championship, and won divisional championships with the Mets, Reds, Orioles, and Nationals.

The 1962 game was tied 4–4 and stopped by curfew after four hours and 11 innings. Three players from the U.S. team made it all the way to the big leagues, including two slugging outfielders. The right fielder represented Boston and had a “can’t miss” label. Tony Conigliaro went 1-for-3 in the game and enjoyed a fine, but shortened, career with the Red Sox. Ron Swoboda played left field in the 1962 game but was more noted for his play in right field with the Mets.

One player who caught everybody’s eye in 1963 was San Antonio’s Freddie Patek. He stood only 5’5″ but packed a wallop. Patek was drafted by the Pittsburgh Pirates with their 22nd pick (434th overall) in the first amateur draft in 1965 and made it to the majors in 1968 with the Bucs. After three years with the Pirates, he was traded to the Kansas City Royals. With the Royals, he was named to three All-Star teams and was part of three consecutive divisional champions that lost in the League Championship Series to the Yankees.

The U.S. Stars lineup featured a Maryland slugger who was drafted in the first round in 1965. He first appeared with the Angels in 1968, but traveled often during his 15-year major league career. Jim Spencer was chosen to the American League All-Star team in 1973 and received two Gold Glove awards during the course of his career. In 1978, he returned to Yankee Stadium as a member of the Yankees and once again was on the same field with Patek in the Bronx for the League Championship Series.

The 1965 game was the last Hearst Sandlot Classic played in New York. The demise of the game was hastened by two New York City newspaper strikes. The first extended from December 8, 1962, through March 31, 1963. The second lasted for 23 days between September 16 and October 8, 1965. The losses from this strike were such that it effectively shut down the New York Journal-American which was the force behind the game. The Journal-American ceased publication on April 24, 1966.

Sandlot All-Star games, however, continued in New York through 1970, as the Yankees Juniors and Mets Juniors faced each other in the Greater New York Sandlot Alliance All-Star Game.

In the 1970 game at Yankee Stadium, the Yankees Kids beat the Mets kids 8–5, and the MVP was Edward Ford. His father, Whitey, had played in the first Brooklyn Against the World Series in 1946. In 1974 the younger Ford was the number one draft pick of the Boston Red Sox. The shortstop made it as far as Triple A Pawtucket, but reality set in in 1977.

Two years earlier, in 1968 at Shea Stadium, the experience of 18-year-old Ruben Ramirez showed that the game’s mission had been fulfilled. He had two triples, drove in five runs, and was selected as the MVP in a game won by the Yankees Juniors, 6–2. It was beyond the ball field that the full impact of the game was felt. Ramirez, never played Organized Baseball, but, based on his performance in the game, he was offered a scholarship to Long Island University and went on to a successful career as an educator. Thirty-one years later, in an interview with the New York Daily News, he said, “That game was the most important day of my life. If it wasn’t for that day, I don’t know if I would have graduated college, let alone be where I am today.”25

Note: This article has been modified from its original version.

ALAN COHEN is a retired insurance underwriter who is spending his retirement doing baseball research. A native of Long Island, he continues to root for the Mets from his home in West Hartford, Connecticut, where he lives with his wife Frances and assorted pets. He did a presentation on “Baseball’s Longest Day: May 31, 1964” at the 50th Anniversary of the New York Mets Conference in April 2012. His biographies of Gino Cimoli, whose career was launched in the Hearst Sandlot Classic, and R C Stevens appear in “Sweet ’60: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates.”

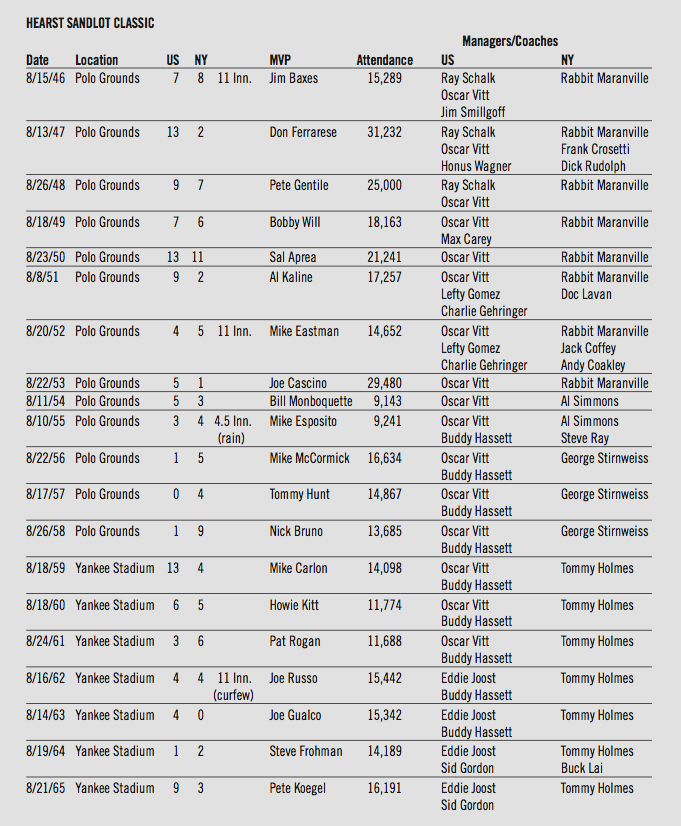

(Click image to enlarge)

Sources

“15th Hearst Sandlot Classic in August,” Milwaukee Sentinel, April 22, 1960. Part 2, 6.

1960 Annual Hearst Classic: U.S. All Stars vs. NY All Stars: Official Program

“Alex, Knutson Named for Trip to Hearst Sandlot Classic,” San Antonio Light, July 22, 1959: 46.

“Corbo to Start for U.S. Stars,” San Antonio Light, August 28, 1958: 27.

“Hearst Stars Return Home Today,” Milwaukee Sentinel, August 13, 1954: Part 2, 4.

“Joost Subs for Vitt as All-Star Skipper,” San Antonio Light, June 24, 1962: 5-C.

“Cleveland Indians Sign Russ Peck to Contract,” Altamont Enterprise, August 15, 1958: 1.

“Kase, New York Sports Editor Retires,” The Sporting News, May 7, 1966.

“New Yorkers Defeat U.S. Stars,” San Antonio Light, August 11, 1955: 12.

“Ruth to Aid Hearst Star Game,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 25, 1947: B–3.

“Texan Frazier starts for U.S. All-Stars,” San Antonio Light, August 14, 1963: 73.

“Week of Thrills for Stars,” San Antonio Light, August 28, 1958: 27.

Hugh Bradley. “All-Star Yankee: Sandlot Classic set goal for Morgan,” New York Journal American, August 7, 1951, 18.

Lester Bromberg. “Yankees ‘Bonus baby’ Star in Four Sports in High School,” The Sporting News, February 10, 1954, 5-6.

Lou Chapman. “Five Hearst Contest Judges Named,” Milwaukee Sentinel, July 3, 1949. B–3.

Arthur Daley. “Sports of the Times: The Rabbit,” The New York Times, January 7, 1954, 34.

Frank Graham. “Graham’s Corner: Morning at Stadium,” New York Journal-American, August 23, 1961, 33.

Don Hayes. “Two South Texas Baseball Stars Ready for Hearst Sandlot Classic,” San Antonio Light, August 13, 1958, 33.

Al Jonas. “Lefty Gomez to Help Vitt Prepare Hearst All-Stars,” San Antonio Light, August 13, 1950. Section D, 3.

Al Jonas. “U.S. Stars Defeat New York Team in Sandlot Classic,” The Sporting News, August 15, 1951, 28.

Brent P. Kelly. Baseball’s Biggest Blunder: The Bonus Rule of 1953–57. Scarecrow Press, Lanham, Maryland, 1997.

Dylan Kitts. “Dormant Summer Sandlot Showcase is revitalized on Brooklyn Diamonds,” New York Daily News, August 10, 2009.

Barney Kremenko. “U.S. Stars Win Classic,” New York Journal-American, August 22, 1965, 33.

Stanley Levine. “Harrell to Start for Stars; Fitzgerald is Reserve,” Albany Times Union, August 16, 1946.

Max P. Milians. “Hearst Classic Majors’ Bonanza,” Boston Record American, August 11, 1965.

Morrey Rokeach. “Hearst Grads could make All-Star Nine,” San Antonio Light, August 17, 1958, 4-C.

Murray Robinson. “Uniformed, Will Travel,” New York Journal-American, August 22, 1965, 35.

Harry H. Schlact. “The Hearst Sandlot Classic—A Living Memorial to Babe Ruth,” The Milwaukee Sentinel, August 25, 1948, 14.

Dennis Snelling. Glimpse of Fame, McFarland, Jefferson, NC, 1993.

Notes

1. Jack Conway, Jr., Boston Daily Record, July 14, 1953, 33.

2. San Antonio Light, March 31, 1957, 2-C.

3. George Vecsey, The New York Times, January 11, 1989, D25.

4. Daley, The New York Times, January 7, 1954, 34.

5. “Al Simmons Funeral Held at Church of his Boyhood,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 29, 1956, part 2, 1.

6. Boston Traveler, August 6, 1949, 7.

7. Al Wolf, “Sportraits,” Los Angeles Times, August 15, 1946, 9.

8. James J. Murphy, Brooklyn Eagle, August 8, 1946, 1, 15–16.

9. The Amsterdam News, August 3, 1946, 10.

10. Barney Kremenko, New York Journal-American, August 16, 1946, 14.

11. Tommy Kouzmanoff, Milwaukee Sentinel, August 27, 1948, part 2, 3.

12. Al Jonas, New York Journal-American, August 22, 1948, L 27.

13. New York Journal-American, August 23, 1948, 1.

14. Hugh Bradley, New York Journal-American, August 7, 1951, 18.

15. James J. Murphy, Brooklyn Eagle, July 26, 1949, 1, 13.

16. Ben Gould, Brooklyn Eagle, July 21, 1950, 13.

17. Walla Walla Union Bulletin, August 19, 1949, 13.

18. The Syracuse Post-Standard, July 27, 1951, 25.

19. Kelly, 34-37.

20. Bob Lassanske, Milwaukee Sentinel, August 24, 1952 Section B, 5.

21. Kelly, 41–45.

22. “Giants pay $50,000 for L. A. Prep Hurler,” San Diego Union, August 30, 1956, b–4.

23. Kelly, 122–26.

24. Maury Rokeach, New York Journal-American, August 19, 1961, 15.

25. Dylan Kitts, New York Daily News, August 10, 2009.