Borchert Field (Milwaukee)

This article was written by Jim Nitz

In 1888, Athletic Park replaced the Wright Street Grounds as Milwaukee’s primary baseball park. Not only did Athletic Park enjoy two separate lives, but it housed a major league team (1891), a Negro National League club (1923), and an All-American Girls Professional Baseball League team (1944). During its second term, Athletic Park, most often remembered by Milwaukeeans as Borchert Field, was home to the American Association minor league Brewers from 1902 to 1952. The National Football League also counts Borchert Field as a former site as the Milwaukee Badgers (1922-1926) and the Green Bay Packers (1933) played home games on the north side gridiron.

The original Athletic Park was built in late winter and early spring of 1888 at a cost of $40,000. The land, formerly an empty private parcel, was purchased for just under $25,000 on February 14, 1888, by the Milwaukee minor league ball club. After several years of renting the cramped Wright Street Grounds, team management was elated to have its own ballpark on a much larger tract. In addition, Athletic Park was more accessible by street car. Even though it was farther from downtown, the new ballpark was reachable by street cars in less time. The future location of the Lloyd Street Grounds had also been considered, but that property was only available for rent, not purchase.

Athletic Park was situated on a rectangular city block bounded by West Burleigh Street on the north, West Chambers Street on the south, North 8th Street on the west, and North 7th Street on the east. The lot was level and high enough to prevent water problems. The far north side neighborhood was predominantly German with a high density of homes and taverns. It was noted that area property values increased by 50% in 1888 due to Athletic Park and new street car lines.

The 588-by-366-foot plot created a ballpark shape that resembled New York’s Polo Grounds. During its entire life, Athletic Park had very short foul lines (262 to 266 feet), an average center field (380 to 400 feet), and distant power alleys (approximately 425 feet). The angular structure of the stands meant that a fan could not see the complete field while seated in the grandstand. They could view either right field or left field but not both at the same time. The diamond orientation was always straight north.

In 1888, Athletic Park was considered a model ballpark in terms of size and comfort. The arrangement of the stands minimized crowding as the covered crescent-shaped grandstand seated 3,500-3,600 fans. Bleachers flanked the grandstand on each side, and, with the liberal use of standing-room-only tickets, the original Athletic Park could hold 10,000 people. Thirty-two private boxes with an elaborate cupola-style cover sat on top of the two-story-high grandstand roof. Writers and scorers utilized some of these third-story boxes but complained that they were cramped and too high. The ticket booth stood on the corner of 8th and Chambers and a shed sat in the northwest (left field) corner of the lot. One Milwaukee Sentinel drawing and two fire insurance maps are the only known depictions of the original Athletic Park.

Milwaukee opened its fine new facility on May 20, 1888, as somewhere between 6,000 and 8,000 fans saw the Western Association Milwaukees defeat St. Paul. Minor league ball was played at Athletic Park until the team entered the major league American Association late in the 1891 season. This club sported a 16-5 record in its home games between September 10 and October 4 and drew crowds of up to 10,000.

The first Athletic Park never hosted another major league game as Milwaukee lost its franchise after the 1891 season. The facility was used for minor league ball through 1894 and for local games in 1895 and 1896. Athletic Park was then converted to “drill grounds of Troop A of the national guard.” In spring of 1902, Harry Quin, owner of the property, rebuilt Athletic Park in the basic form that it would remain through 1952.

Quin also owned the new Brewers franchise in the minor league American Association. This team, which remained in Milwaukee until the National League Boston Braves arrived in 1953, competed for the fans’ affections with the Western League Creams of the Lloyd Street Grounds in 1902 and 1903. In order to attract fans, a 4,100-seat covered grandstand (painted red) and two sets of 1,500-seat bleachers were constructed. This new park on the old site was built without the ornate cupola of its predecessor.

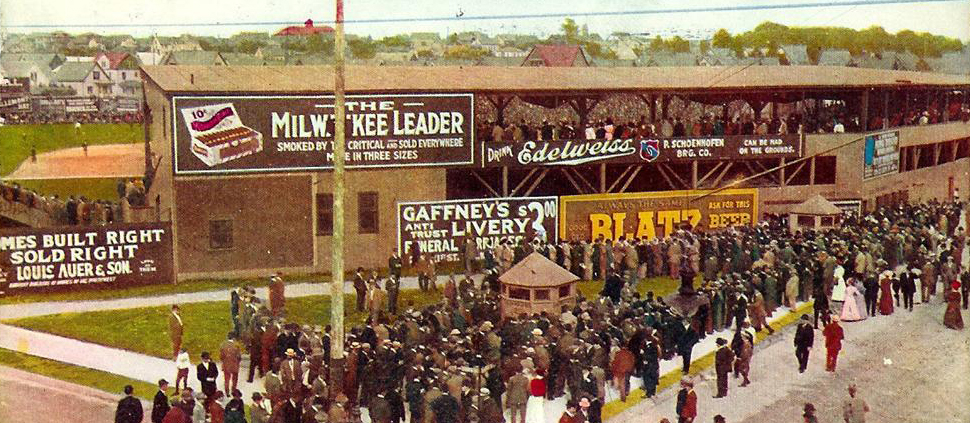

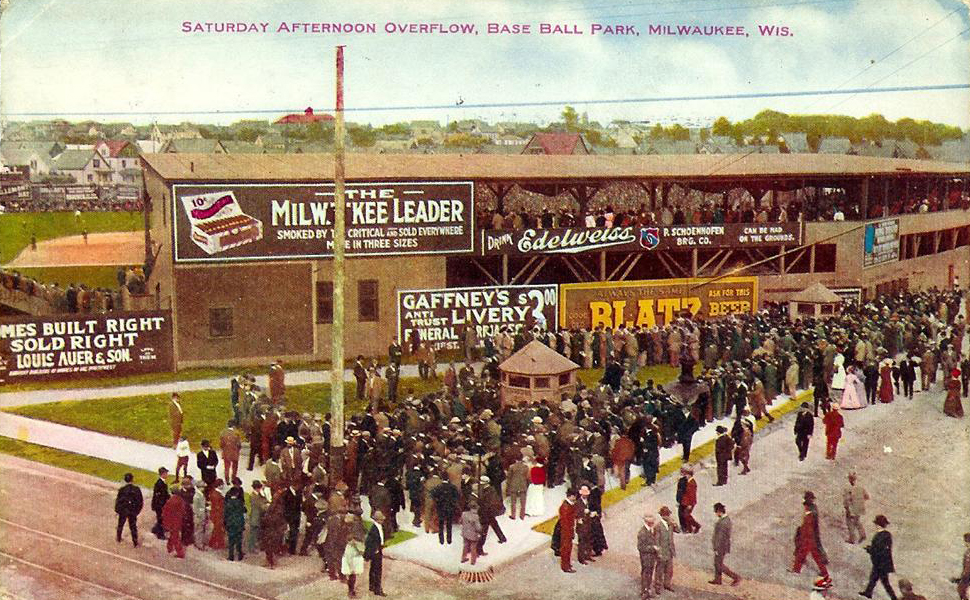

The new Athletic Park opened on Sunday, May 11, 1902, before 5,000-6,000 fans. As the AA team became more popular (the only game in town by 1904), the need to expand Athletic Park became obvious by 1910. The first and third base bleachers were converted into covered grandstands attached to the 1902 24-foot-high stand. A runway was then built that allowed fans easy access to the new left-center-field bleachers. The right-center-field scoreboard, with the locker room behind it, was also erected at this time. Although the exact capacity could never be determined due to the many long bench seats, standing-room-only crowds could reach 18,000.

After 1910, only minor modifications were made to Athletic Park. Lights were added in 1935, and, in 1944, a windstorm tore off a portion of the first base grandstand roof. Because of the advanced age of the park, the roof was never replaced. When Bill Veeck bought the Brewers in 1941, he cleaned and painted a dilapidated Borchert Field. The park had been renamed after the sudden 1927 death of Otto Borchert, the team owner at the time.

In addition to the AA Brewers, Athletic Park also served as the home of the Negro National League Milwaukee Bears from late April to June of 1923. Because of low attendance and a lack of press coverage, the Bears disbanded in August after spending time as a road-only team. Borchert Field was also the home ballpark of the 1944 champion Milwaukee Chicks of Phillip Wrigley’s AAGPBL.

Borchert Field was the oldest park in the AA by the late 1940s and had become archaic and ramshackle. Milwaukeeans now had higher expectations in comfort and sight lines. The residential location made parking difficult as more fans preferred using their own automobiles over public transportation. The last game played at Borchert Field was on September 21, 1952. The Brewers’ lease with Otto Borchert’s widow, Idabell, expired on January 1, 1953. The team was to play their games at the new Milwaukee County Stadium that year. The arrival of the Braves, however, resulted in the Brewers moving to Toledo.

Mrs. Borchert sold her ballpark and the land to the city for $123,000 in 1952 after County Stadium had become a certainty. Interestingly, in 1937, the property had been assessed for $73,000 with only $13,000 attributed to the decaying structure. By late 1952, the demolition of the park had begun and the block was used as a playground until 1963. That year, the Locust Street section of Interstate 43, also known as the North-South Freeway, was completed, running precisely between 7th and 8th Streets. As of 2007, 145,000 vehicles per day pass through the site of Milwaukee’s longest-lasting professional ballpark. Many photographs, in private and public collections, exist of Borchert Field.

Sources

Baist’s Property Atlas-1898. Philadelphia: G. Wm. Baist, 1898.

Coen, Ed. “Early Big Time Teams Left Milwaukee Bitter.” Baseball Research Journal, Volume 14 (1985), 10-12.

Evening Wisconsin, 15 February and 19 and 21 May 1895.

Graber, Ralph S. “Only a Memory: A look at a Few Historic Minor League Ballparks.” Baseball Research Journal 1982, 173-178.

Hauser, Steven. Personal and telephone interviews with this Milwaukee historian. 1992 and 1993.

Hilton, George W. “Milwaukee’s Charter Membership in the American League.” Historical Messenger of the Milwaukee County Historical Society, 30, No. 1 (Spring, 1974), 2-17.

Insurance Maps of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Vol. 4, New York: Sanborn-Perris Map Co., 1894.

Insurance Maps of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Vol. 2, New York: Sanborn Map Co., 1910.

Lowry, Philip J. Green Cathedrals. Cooperstown: SABR, 1986.

Lowry, Philip J. Green Cathedrals. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1992.

Milwaukee County Historical Society. Photo files and microfilm reels.

Milwaukee Daily Journal, 10 January; 17 February; and 21 May 1888.

Milwaukee Journal, 27 February 1895.

Milwaukee Journal, 8 September 1896.

Milwaukee Journal, 17 and 23 January; 25 February; 14 March; and 9 and 12 May 1902.

Milwaukee Journal, 17 March 1910.

Milwaukee Journal, 31 December 1911.

Milwaukee Journal, 30 April 1923.

Milwaukee Journal, 7 June 1935.

Milwaukee Journal, 1 December 1952.

Milwaukee Journal, 18 and 22 January and 11 June 1953.

Milwaukee Journal, 14 April 1957.

Milwaukee Journal, 2 December 1963.

Milwaukee Journal, 23 June 1978.

Milwaukee Sentinel, 26 December 1887.

Milwaukee Sentinel, 9 January; 15 February; 16 April; 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, and 21 May 1888.

Milwaukee Sentinel, 21 September 1891.

Milwaukee Sentinel, 8 September 1896.

Milwaukee Sentinel, 14 March and 12 May 1902.

Milwaukee Sentinel, 14 April 1953.

Morgan, Thomas J., and James R. Nitz. “Magical Borchert Field.” Milwaukee History: The Magazine of the Milwaukee County Historical Society 15 (1992): 98-111.

Pfennig, Marvin. Telephone interview with the former Borchert Field usher. 27 January 1992.

Randolph, Pepi. Telephone interview with the assistant general counsel of the Milwaukee Brewers. 11 May 1993.

Rascher’s Fire Insurance Atlas of the City of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Vol. 3. Chicago: Chas. Rascher, 1888.

Thorn, John, and Pete Palmer, eds. Total Baseball. Second ed. New York: Warner, 1991.

“2007 Milwaukee Area Freeway System #2, Milwaukee County Annual Average Daily Traffic.” Wisconsin Department of Transportation. 17 January 2009.

http://www.dot.wi.gov/travel/counts/docs/milwaukee/milwaukee-freeway2007-pt2.pdf

Veeck, Bill, and Ed Linn. Veeck-as in Wreck. New York: Bantam, 1962.

Ziedler, Frank. Telephone interview with the former Mayor of the City of Milwaukee. 10 January 1992.