Olympic Stadium (Montreal)

This article was written by Rory Costello

Editor’s note: This article was selected as a winner of the 2014 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award.

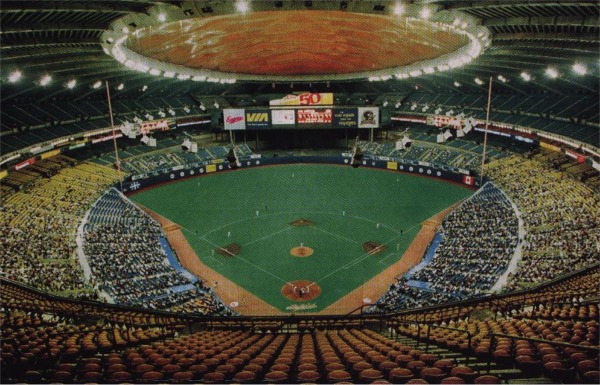

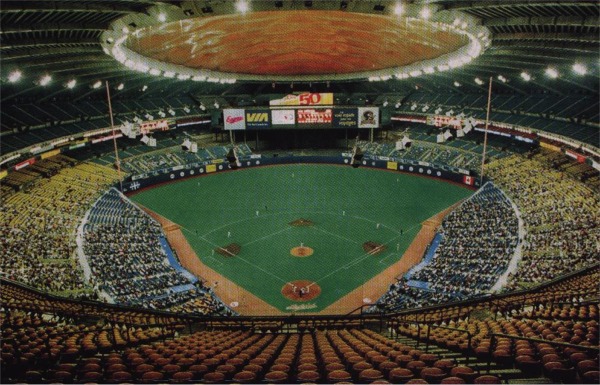

The Montreal Expos played 36 seasons (1969-2004). For the last 28, their home was Olympic Stadium – a cavernous concrete edifice built for the 1976 Summer Olympic Games. From the outset, “The Big O” was notorious: hailed as a marvel of architecture and engineering … and blasted as a white elephant. The Expos were originally supposed to be out of little Jarry Park by 1972, but they had to stay there much longer than originally intended – eight seasons, and very nearly a ninth.

Ballooning costs led to an alternate nickname for Olympic Stadium: “The Big Owe.” Not only did construction of its base run vastly over time and budget, its special features – the Montreal Tower and retractable roof – made it an ongoing money pit. The permanent roof installed in 1998 became a liability in turn. The province of Quebec didn’t finish paying off the Olympic facilities until November 20061 – two years after the Expos had departed to become the Washington Nationals. As of 2013, the decaying main structure still stood, seldom used. A debate remained ongoing about which was better, renovation or demolition. Either way, another hefty bill would be in store, because conventional implosion was not possible.2

Le Stade du Parc Olympique de Montréal3 (its official name in French-speaking Quebec) has hosted many other events besides baseball. They include Canadian and American football, soccer, boxing, rock concerts, opera, and religious gatherings. The Expos were the primary tenant, though, and baseball was never truly suited to The Big O. Jean-Pierre Roy, the Montreal-born pitcher who became one of the original Expos broadcasters, said in 2004, “In the big Olympic Stadium, one got lost.”4 Charles Bronfman, who was the club’s primary owner from its inception until 1990, seconded this view in 2011. “In Olympic Stadium the fun [of intimate Jarry Park] dissipated pretty damn fast. That wasn’t a ballpark.”5

From 1997 through 2004 the Expos ranked last in the National League in attendance, and the feeling of huge empty space grew more pronounced (43 “home” games took place in San Juan’s Estadio Hiram Bithorn – even smaller than Jarry Park – in 2003-04). Even before then, ahead of the 1992 season, the team had reduced baseball seating capacity from nearly 60,000 to less than 44,000. When the top was open, it could be chilly, but not much light got in. Yet another negative was artificial turf. In 2010 catcher Gary Carter said of himself and another former Expos hero, André Dawson, “We played in that god-awful Olympic Stadium that tore our knees up.”6

Even so, when things were going well, this place still offered a good time at the ballgame. Except for the strike in 1981, the Expos did draw more than 2 million fans each year from 1979 through 1983, when the roster included Carter, Dawson, and assorted other homegrown stars. During that five-year stretch, they drew well above the NL average, ranking either third or fourth among 12 clubs. They never got above eighth after that, despite some good teams – especially the 1994 edition, which had the best record in the majors before the sport’s most crushing strike halted the season.

And though they weren’t often big, the crowds did their best to fill the void. There was something likably goofy about joining in for the chuckling refrain of the team’s unofficial theme song, “The Happy Wanderer,” and watching the antics of the furry orange mascot, Youppi!.7 Tickets were reasonably priced too – at least as late as 1985, it was still possible to buy a bleacher seat for a “loonie” (one Canadian dollar coin). At the then-prevailing exchange rates, that was less than US$1. Surely that had to be the cheapest remaining price of entry for what was once the common man’s entertainment. One could settle in with a good Canadian beer or two and a smoked meat sandwich, even if it wasn’t on par with what Montreal’s best delis purvey.

The story of Olympic Stadium revolves around Jean Drapeau (1916-1999). This man of vaulting ambition was the mayor of Montreal for nearly 30 years (1954-57; 1960-86). The Canadian Encyclopedia calls Drapeau “the most daring and successful mayor Canada has ever seen.” It adds, “He gave the city its greatest moments: [the] 1967 World Exposition … and the 1976 Summer Olympic Games,” also stating that “he single-handedly brought Montreal a major league baseball team, the Montreal Expos.”8

The latter is an overstatement; many other people played prominent roles in attracting the Expos and getting them off the ground. Yet there is no denying that Mayor Drapeau was largely responsible for solving the new franchise’s biggest problem: where it was going to play. In August 1968, it really looked as though Montreal would lose its expansion award to another city – but a last-ditch effort brought forth Jarry Park as a venue acceptable to Major League Baseball. The city also pulled off a crash upgrade project, despite harsh winter conditions, to have the stadium ready for the home opener in 1969.

The Olympics were another part of Drapeau’s vision. The mayor sought “to make his beloved Montreal one of the world’s great cities.”9 This Byzantine story has inspired at least three full books, lengthy passages in others, and innumerable articles. To summarize, the mayor had originally come up with the idea as far back as 1963. In 1966 Montreal bid for the 1972 Summer Games but finished second to Munich. Yet Drapeau pressed on. In May 1968, the Canadian Olympic Association approved Montreal as Canada’s bidder for the ’76 Games over Toronto and Hamilton. Finally, in May 1970, it won the global contest over future hosts Moscow and Los Angeles (Florence withdrew).

That October, Drapeau and his party enjoyed a sweeping victory in the municipal elections. As The Canadian Encyclopedia put it, “The absolute power Drapeau won in that election allowed him to ram through his plan for the Olympics, whose massive white concrete structures incarnated his politique de grandeur.”10

The man who executed – and expanded – Drapeau’s grandiose scheme was Roger Taillibert. Taillibert was chief architect of civic buildings for the city of Paris. The mayor’s choice of a non-Canadian prompted the predictable nationalist backlash in some quarters. Drapeau saw the Frenchman as a great artist, however, later saying, “Taillibert is the kind of architect who built the cathedrals of ancient times.”

Taillibert was and is esteemed in architectural circles for his design concepts. However, his role in the 1976 Olympics was revealed only in March 1972 after a Montreal Gazette sportswriter dug into the story and found that the choice had been made not long after Montreal was awarded the Games. In a main editorial, the newspaper wrote, “It is extraordinary that even in Montreal’s municipal autocracy the mayor would keep such an important matter … a secret for so long. It is amazing, moreover, that he has been able to [do so].”11

The Gazette praised Taillibert for his design of the Parc des Princes soccer stadium in Paris. But the editorial concluded, “We need an Olympic Stadium that will accommodate the sports that produce revenues in North America, such as baseball and Canadian (or American) football. We cannot afford a stadium that will turn into a monument after 1976. To be a success in the long run, it will have to be the first National League ballpark designed in France.”

On one level, philosophy transcended culture. When Taillibert published his memoirs in 2010, he told La Presse (a French-language newspaper of Montreal), “A stadium ought to be able to open itself to welcome track, soccer, rugby, or baseball.”12 So he was an adherent of the multi-use stadiums that marked the 1960s and 1970s. More than a decade would pass before Baltimore’s Camden Yards ushered in a new era of cozier, retro-style baseball-only stadiums.

Camden Yards also brought back an emphasis on downtown locations – and this was something else that The Big O lacked. That’s understandable, considering that it was part of a set of installations. The Montreal Métro also extended its Green Line as part of the Olympic effort. The Pie-IX station, which serves the stadium, is just six stops from the city’s biggest mass transit hub, the Berri-UQAM station.13 To drive, it’s about 20 minutes from downtown. That’s not onerous (for example, New York’s Citi Field is much further removed from Manhattan) – but not altogether convenient either.

On another level, though, a clash arose. It’s certainly possible for investment in the arts and culture to pay off. In the case of Olympic Stadium, though, dreams and artistic principles overwhelmed utility, time, and money. Drapeau was often compared to another longtime mayor, Richard Daley, Sr. of Chicago, because they headed city machines that relied on pork-barrel politics. Author Henry Milner viewed the more fitting comparison, however, as Robert Moses, the power broker who transformed New York City with his massive public works.14

The Expos were originally supposed to play in an interim park for just three seasons. “We based our decision to accept Montreal into the league on the promise that a domed stadium would be built,” John Galbreath, a member of the National League expansion committee, was quoted as saying when the franchise was awarded.15 John McHale, who was then working as the chief aide to Baseball Commissioner William Eckert, was an eyewitness to Drapeau’s promise to Eckert and the NL owners.16 In a matter of months, the very capable and respected McHale would become president (and 10 percent owner) of the Expos.

In late August 1968, shortly after the franchise was saved for Montreal, local sportswriter Ted Blackman wrote again that plans were being prepared for a dome in 1972. He did note, though, “It is still not certain that Montreal will build a domed park for 1972, although Drapeau is privately committed.”17

Indeed, that November Blackman reported, “The city originally promised a 60,000-seat domed stadium for the 1972 season, hedged on that, and now apparently has set a 1975 date as the earliest possible opening date for a permanent park.” He also observed that there were one-year lease options on Jarry running through 1984.18

In May 1969 skeptics (such as New York sportswriter Dick Young) were raising doubts that formal plans for a new Expos stadium existed. They were right, one reason being the uncertainty that Montreal’s bid for the Olympics would succeed (though Drapeau had long been doing his best to woo the International Olympic Committee). Ted Blackman wrote, “Should the bid fail, Drapeau will order sketches of a 50,000-seat stadium with an umbrella-type roof – costing, he hopes, no more than $20 million.” He also quoted a remarkably optimistic Charles Bronfman. “I’m not the least bit worried the city won’t keep its commitment,” said the principal owner. “The city made promises and kept them along each step of the way. I’m not convinced we must spend $50 million for a domed stadium, but we are examining new ideas and concepts of a covered stadium. Such as an umbrella type. When? About 1973, I should think.”19

In May 1969 skeptics (such as New York sportswriter Dick Young) were raising doubts that formal plans for a new Expos stadium existed. They were right, one reason being the uncertainty that Montreal’s bid for the Olympics would succeed (though Drapeau had long been doing his best to woo the International Olympic Committee). Ted Blackman wrote, “Should the bid fail, Drapeau will order sketches of a 50,000-seat stadium with an umbrella-type roof – costing, he hopes, no more than $20 million.” He also quoted a remarkably optimistic Charles Bronfman. “I’m not the least bit worried the city won’t keep its commitment,” said the principal owner. “The city made promises and kept them along each step of the way. I’m not convinced we must spend $50 million for a domed stadium, but we are examining new ideas and concepts of a covered stadium. Such as an umbrella type. When? About 1973, I should think.”19

John McHale expressed prophetic doubts in October 1970 about the successor park’s lack of charm and intimacy. He added, “Frankly, I don’t see how we can have a combined stadium either. But I don’t want to underestimate the mayor’s ability of coming up with something.” With regard to possibly upgrading Jarry Park, McHale noted that the club would have to be certain (from a cost-benefit standpoint) that it would stay there for at least 10 to 20 years before committing to such a project. 20

In April 1971 Expos general manager Jim Fanning was still targeting the 1975 season as the move-in date for Olympic Stadium.21 That hope remained alive a little over a year later.22 Just a few weeks after that, however, John McHale acknowledged that 1977 was the target date, though he held out hope that some games might be played in the new facility after the Olympics.23 Meanwhile, the Expos made do at Jarry Park.

It is interesting now to see such a realistic outside opinion about when The Big O would be ready – even before the tragicomedy of construction became apparent. Labor strikes, inflation, and bad winter weather in Montreal were factors.24 But aside from these forces majeures, incompetence, corruption, and hubris were at the heart of it.

It started with an inability to produce plans. This was evident in expanding estimates of raw material costs (e.g., prefabricated concrete). Claude Phaneuf, an engineer for the city, later testified that in late 1973, he sent a series of letters to the consulting engineering firm, Régis Trudeau et Associes, asking whether the firm had put enough competent people to work on the project. Phaneuf also found that the firm “understood nothing” about erecting the structure, including how to move the 40-ton cement building blocks. 25

The sheer technical complexity of the project, with its 34 giant cantilever beams, was truly daunting. But to compound matters, it later emerged that Drapeau’s right-hand man, Gérard Niding, steered the job to Trudeau’s firm, which built a country house for Niding. That wasn’t the only clear impropriety.26

What’s more, the City of Montreal’s public-works director recommended in 1974 that public bids for construction of the stadium be waived because of the need to begin building immediately. “This was a normal procedure that permitted us to save time and thus reduce the cost of construction,” said the engineer, Charles Boileau.27

Roger Taillibert’s attitude was also a major issue. According to the Montreal Star, the architect said, “The stadium is a work of art. Never, never, never did we think of changing the design. It would have been like carving a beautiful statue of bronze … and then, as costs went up, completing it with feet of wood.” The Star said that Mayor Drapeau developed an “almost worshipful attitude toward Taillibert, who not only dictated design but insisted on estimating prices, negotiating contracts, and influencing the selection of contractors.”28

In August 1974 the province of Quebec removed Taillibert in a reorganization (his multimillion dollar fees remained a lingering issue). It took construction of the stadium from the City of Montreal and appointed a Montreal-based firm called Lavalin Inc. as project manager. A consortium known as Désourdy became the general contractor.29 These firms were cronies of the Liberal Party, which then controlled the provincial government. According to Claude Phaneuf, that’s when things turned sour. He noted that his team had successfully built the Vélodrome (bicycling arena) and the Olympic Village when Quebec took over and fired Taillibert. He maintained that his team would have completed the stadium on time if given the chance. Drapeau kept saying that Montreal’s know-how and tight management made the provincial government jealous, which is why they took over.

In December 1975 the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation devoted a segment of its program The Fifth Estate to an interview with Taillibert. The CBC Digital Archives’ notes say, “The enigmatic Taillibert discusses his architectural philosophies and smugly dismisses all critics with this blanket statement: ‘There are always critics; only those who do nothing have no critics.’ ”

That same program gave Montreal City Councilor Nick Auf der Maur a chance to make a counterpoint. According to the CBC Digital Archives, “He derides Drapeau for demanding a grand ‘pyramid builder’ like Taillibert, instead of hiring another architect who would do a simpler, less expensive job.” Auf der Maur was the spokesperson for the Montreal Citizens’ Movement, a group that opposed Drapeau’s Olympic plans. In 1976 the one-time journalist released a book called The Billion-Dollar Game that prefigured official inquiries.

When Michael Farber of the Montreal Gazette interviewed Taillibert in 1986, he found the architect charming and humorous, yet also arrogant, unremorseful, and flippant. “During the conversation, he [Taillibert] blithely said, ‘What is money? Mere paper.’ The bottom line, Taillibert said, will not be the figure some pencil pusher comes up with when the final bill is stamped ‘paid’ years from now, but what sort of heirloom Montreal will pass on to its children.” In his view, Olympic Stadium transcended “cookie-cutters” like those in Pittsburgh and Cincinnati. He used the lofty French term patrimoine, likening his creation to the Eiffel Tower and other landmarks of French architecture.30

It’s not really certain what the original budget for Olympic Stadium was. In April 1972 the Canadian Press wrote that Drapeau “wouldn’t say how much it will cost, beyond reiterating that the cost would be kept within the overall Olympic financing figure he has been sticking to – C$124 million.”31 Not long after, though, he casually announced a new projection: C$310 million. As the Montreal Gazette wrote in 1986, “It was the first quantum leap in both cost and credibility.”32 Drapeau long insisted that the Montreal Games would be “self-financing” – indeed, he said, “It is no more possible for the Montreal Olympics to lose money than it is for a man to get pregnant.” Among other things, he placed unfounded hope in “extraordinary revenue” from commemorative coins, stamps, and souvenirs.

Ultimately, by a 1978 estimate, the tab for the Olympics ran up to C$1.27 billion – with the unfinished stadium accounting for half that sum.33 Even a combination of real-estate taxes (specifically labeled “Special Olympics Tax”), tobacco taxes (C$0.10 per pack of cigarettes), and proceeds from the Canadian national lottery could not cover it all.34 Various other figures have circulated. In 2008, however, Forbes magazine put the stadium’s total price tag (adjusted for inflation to that point) at US$1.4 billion.35

Indeed, in late 1975, it got to the point where the Province of Quebec established the Olympic Installations Board (OIB) for oversight. In July 1977 a special probe into spending on the Games – the Malouf Commission – was launched.36 The report came out in June 1980; a summary of its conclusions itself ran to 88 pages.37

Were the delays and cost overruns caused by Montreal or Quebec? We may never know. But the Liberal Party lost the provincial elections of November 1976 amid general discontent. Lavalin became embroiled in a corruption scandal (unrelated to the stadium) in 2013. To say the least, the turnover in management during construction of an undertaking like the stadium was highly unusual.

Once construction actually got going, an industry malpractice was visible –featherbedding. In early 1976 at least 100 cranes to lift the concrete pieces into place were on site, though eight would have sufficed under normal conditions and with enough time. Each crane was rented for as much as C$160 an hour, but most handled no more than one or two pieces a day. Reportedly it was about paying crane operators.38

It was touch and go, but the showcase was usable in time for the Summer Games in 1976 – although the Montreal Tower was incomplete, so the roof was not in place either. For the Olympics, the stadium held 72,000 people. What may be less remembered is that its field was natural grass.39

Track and field was the main competition held in the new stadium.40 The biggest stars were Alberto Juantorena of Cuba (double gold medalist in the 400- and 800-meter runs), Lasse Virén of Finland (who repeated his double of the 1972 Games by winning both the 5,000- and 10,000-meter runs), and Bruce Jenner of the US (who set a world record while taking gold in the decathlon).

The first regular tenant to play in Olympic Stadium was the Montreal Alouettes of the Canadian Football League, in July 1976. The Alouettes have had a checkered history. They folded after the 1981 season, and were replaced by the Montreal Concordes from 1982 through 1985. The team was rechristened the Alouettes for the 1986 season, after which it ceased operations again. A replacement franchise was granted to Baltimore; this club moved to Montreal starting with the 1996 season. The new version of the Alouettes played two regular seasons at Olympic Stadium (1996 and 1997) and continued to hold playoff games there because capacity is greater.

The dimensions of the football field under Canadian rules are both longer (110 yards, with 20-yard end zones) and wider (65 yards). This was another element of Olympic Stadium’s multi-use design, to the detriment of baseball.41

A CFL database (cfldb.ca) gives Olympic Stadium’s football capacity as 58,500 for the 1976 season – when the natural grass from the Olympics was still in place – and 66,308 from then through 1986. For 1996, it was 56,245; for 1997, it was just 33,900. The Alouettes first moved back to little Percival Molson Stadium – their home back in the 1950s and ’60s – because the superstar rock band U2 had been booked for The Big O on the same day a 1997 playoff game was scheduled.

As the end of 1976 approached, the Expos still had not completed final lease arrangements for Olympic Stadium. On the eve of the provincial elections, Charles Bronfman stated publicly that if the Parti Québécois (which advocated sovereignty for Quebec) beat the Liberals, the Bronfman family could move its Seagram’s liquor business and the Expos out of Montreal. Lo and behold, the PQ won, and a lease agreement in principle was held up because of the unexpected change. Bronfman was quick to apologize. Still, the PQ minister responsible for the Olympic Installations Board, Claude Charron – an Expos fan – rattled sabers with the team and laid into John McHale for trades gone wrong.42

The possibility still lurked that at the beginning of the 1977 season, the Expos might have to play home games in Jarry Park or even in other cities. The “dragging of feet,” as McHale termed it, caused the National League to shift the 1978 All-Star Game from Montreal to San Diego.43

The uncertainty lingered into January 1977, when talks between the Expos and the OIB were described as “very, very sour.” When asked about whether the team could wind up returning to Jarry, McHale said, “That is a distinct possibility.”44 Indeed, the Expos also announced that month that they would sell 1977 season tickets on the basis that the team would continue to play at Jarry. Finally, in February 1977 the Expos and OIB came to terms, and an official announcement came in early March. “Jarry Park was quaint and fun,” said a relieved McHale, “but that kind of thing really wore itself out.”45

The Expos played their first game at Olympic Stadium on April 15, 1977. They lost to the Philadelphia Phillies, 7-2, as Steve Carlton beat Don Stanhouse. It was a sunny day outside – but chilly within, prompting Philadelphia sportswriter Bill Conlin to say, “I think you’ve got a larger Candlestick Park.” The big crowd – 57,592 – also had a hard time getting in. An incredulous McHale said, “The RIO [French acronym for the OIB]46 couldn’t find the keys to the doors. They had to use a hacksaw on the chains for the ones they did open. Imagine, all the locks in this place and there isn’t one master key.”47

The first player to hit a home run at The Big O was Montreal’s right fielder, Ellis Valentine (off Carlton in the first game). Over the years, Vladimir Guerrero amassed the most homers for the home team, 122. Among visitors, Mike Schmidt led with 32.48

These were the most impressive in terms of distance:

May 20, 1978: Willie Stargell of the Pittsburgh Pirates drove a pitch into the second deck in right field – the only fair ball ever to reach the 300 level. “Pops” was known for his many tape-measure blasts; this one was estimated at 535 feet, and a yellow seat was installed to mark the spot. “One of the most awesome things I have ever seen in my life,” said Expos pitcher Rudy May. Wayne Twitchell, the pitcher who gave up both of Stargell’s homers that afternoon, said, “He made perfect contact. … (T)his ball made it to the upper deck in a heartbeat. … (I)t was like trying to watch a tracer bullet. …(Y)ou could hear it when it hit. … I was kind of in shock.”49

April 4, 1988: On Expos’ Opening Day, Darryl Strawberry of the New York Mets hit a ball off a rim of lights just below the orange roof of the stadium. A McGill University physics professor estimated that it would have carried 525 feet if its flight had not been interrupted.50 Expos reliever Randy St. Claire served up the homer (Strawberry’s second of the day).

June 15, 1997: Henry Rodríguez of the Expos became the only other man to match Strawberry’s feat. His ball bounced up off the 160-foot-high concrete rim in right field, hit the roof, and came down to hit a speaker. The victim was Brian Moehler of the Detroit Tigers.

The first man to hit the rim was another slugger known for long distance – but he did not get credit for a homer. That was Dave Kingman (then with the Mets), who unloaded one to left field off Montreal’s Jackie Brown on June 1, 1977.51 Gary Carter later recalled, “The umpires didn’t know what to call it. They finally called it a foul ball.”52 As a result, orange foul lines were painted on the rim.

On the pitchers’ side of the ledger, these two no-hitters were the greatest feats at Olympic Stadium:

May 10, 1981: Charlie Lea’s for the Expos against the San Francisco Giants.

May 23, 1991: Tommy Greene’s for the Phillies against Montreal.

The largest paid crowd of any kind at Olympic Stadium – 78,322 – came when Pink Floyd played on July 6, 1977. It was the last date on the “In the Flesh” Tour that supported the Animals album. Bassist Roger Waters got exasperated and spat in the face of an obnoxious fan sitting in the front row. This episode and the feelings it engendered in the band inspired their next album The Wall.53

At least a few football games rivaled that crowd and exceeded stated capacity. One of them was the 1977 Grey Cup (the CFL’s championship). That game on November 27 was known as “The Ice Bowl” because melted and refrozen snow turned the field into a sheet of ice. It was also called “The Staples Game” because the ice prompted the Alouettes, led by defensive back Tony Proudfoot, to get traction by putting staples in the soles of their shoes. Despite the aftermath of the blizzard and a transit strike, 68,205 fans made it out – many on foot – to see the 41-6 win over the Edmonton Eskimos.

In August 1978, well into the Expos’ second season at Olympic Stadium, Charles Bronfman and John McHale talked about baseball there. Bronfman, then as later, did not like it. “There’s no sun, there’s so much concrete, the building overpowers the game, if there’s a big crowd the stadium seems empty. Baseball is a summer leisure activity. That is not a summer leisure stadium.”

McHale talked about how advance sales, which made up 70 percent of the total gate at Jarry, had fallen off to 50 percent at The Big O. He said, “When you go from 30,000 seats to 60,000 you change people’s buying habits. You know you can always get a seat in Olympic Stadium. You didn’t know that at Jarry. A guy who doesn’t buy in advance is subject to all the reasons for not going.” He sounded the theme of intimacy again too. “The great thing about a ballgame is to be down there where you can see the strength of the players’ arms, the expressions on their faces when they’re called out, and to hear what they say to the umpire.” Without the roof, he added, the stadium had the worst of both worlds: “sunless but open to the elements.”54

Yet the best era ever for The Big O was right around the corner. On July 27, 1979, the Expos set their single-game attendance record with 59,260 – and broke it on September 16 with a crowd of 59,282. It was a doubleheader against the St. Louis Cardinals, and after Montreal won the nightcap (getting a split), the Expos led the NL East with a winning percentage of .604 – just .001 ahead of the Pittsburgh Pirates. In five of their final six home games that year, more than 50,000 fans were on hand. Going into the last game of the season, Montreal was still just one game behind Pittsburgh – but a playoff was not to be. In their finales, the Pirates won and the Expos lost.

During this period, other noteworthy events took place at Olympic Stadium – including the first fight between the great boxers Sugar Ray Leonard and Roberto Durán. “The Brawl in Montreal,” as Sports Illustrated billed it, took place on June 20, 1980, before 46,317 fans. Leonard, returning to the city where he had won Olympic gold, lost his welterweight title to “Manos de Piedra” in a 15-round battle of slugging, skills, and will. Quite a few fight aficionados call it one of the best bouts ever.55

The baseball crowd also exceeded 54,000 for the first two games of the National League Championship Series against Los Angeles in 1981. After a rainout on Sunday, plus more rain and severe cold, only 36,491 made it out for the deciding game the next day. October 19 is also known in Montreal as “Blue Monday” because the Expos’ best chance at going to the World Series slipped away in the ninth inning. By coincidence, the man who hit the game-winning homer that day was Rick Monday of the Dodgers. The Expos never made it back to the postseason.

Olympic Stadium did finally host the All-Star Game, on July 13, 1982 – the first time it was held outside the United States. Though the stadium’s single-game baseball attendance mark was expected to fall, the crowd of 59,057 was just short. The fans voted in three Expos as starters that year: Tim Raines, André Dawson, and Gary Carter. A fourth, pitcher Steve Rogers – who had given up Monday’s homer the previous fall – also started. He got the win for the NL.

From 1981 through 1983, a North American Soccer League team called the Montreal Manic played in Olympic Stadium. Attendance was pretty good by NASL standards the first two seasons – over 20,000 per game. However, the franchise still lost a lot of money, and after crowds fell off in 1983, the Manic folded.

Before the 1983 season, amid a leasing dispute with the Olympic Installations Board over Olympic Stadium, speculation arose that the Expos might move temporarily to Vancouver or New Orleans. McHale again cited the competitive disadvantages the franchise faced with high rents and other costs at The Big O, along with the weakness of the Canadian dollar.56 The key dispute was over control of revenues from advertising and promotion sold inside the stadium. The sides agreed that rent would remain at 1982 levels while talks continued. At the end of July they finally agreed on a new lease that extended through the 1987 season – and covered the replacement of the dangerously frayed artificial turf.57

In 1985 the OIB hired Lavalin to complete Olympic Stadium’s tower – at a proposed cost of C$125 million. Previously, in 1980, the Quebec government had halted work because engineering reports indicated that the structure would not be strong enough to support its own weight.58 Lavalin used concrete reinforced with steel rods instead of solid concrete and finished the job on schedule (and budget!) in 1987. The finished tower stands just over 541 feet (165 meters) – not as high as originally planned. Even so, it is the tallest leaning tower in the world, inclined at a 45-degree angle. A glass funicular takes visitors to the top.

The completion of the tower enabled the installment of the retractable roof at last. The spools of silver-and-orange rubberized Kevlar had been in storage for six years in Marseilles, France. Then after 1982, they had been stashed under the stadium. “We’ve been promised this since 1972,” said John McHale in 1985, after the Quebec government greenlighted the final stages of the tower and roof project. “It’s one of those things you’ve been promised for so long that you won’t believe it until you see it.”59 By the time the Expos played their first game under the roof (April 20, 1987), McHale had stepped down as club president.

Even before it was in place, Lavalin had warned that the roof could not be operated in winds exceeding 25 miles per hour. As it turned out, the Kevlar tore during the first attempt at raising.60 In the end, the roof was actually opened and closed a total of only 88 times.61 For much of its existence, it hung from the tower like a great slumbering bat – but it was kept closed starting in 1992, even though it was also prone to leaking. Some believed that the roof did not work properly because Lavalin had modified Taillibert’s plans.

While the CFL was absent from Montreal, there was still sporadic football action at Olympic Stadium. In 1988 and 1990 NFL preseason games were played there. In 1991 and 1992 it was home to the Montreal Machine of the World League of American Football, a springtime developmental league set up by the NFL. On June 6, 1992, the league’s championship game, World Bowl II, took place at The Big O before 43,789 fans.

Major renovations began at Olympic Stadium in 1991. For details of all the reconstructive surgery (plus dynamic diagrams of the stadium’s various layouts), a succinct account may be found on Andrew Clem’s baseball blog. The main goal was to bring baseball fans closer to the action. It helped to a degree, but the setting was still overwhelming.

Jonathan Kay, a columnist for Canada’s National Post newspaper, commented on the scale issue in 2012. “As seen from a distance, the Olympic Stadium was, and remains, a genuinely majestic and imposing structure. … Yet it also must be said that there is something vaguely totalitarian about the Stadium’s architectural style. The function of totalitarian architecture – as with great cathedrals – is to make humans feel small, and thereby encourage them to throw themselves into a collective cause or belief greater than themselves. But in the domain of sports, the sheer size of a venue can make all of mankind seem impotent.” Kay’s perceptive article had another vivid image: “The spiny creature [i.e., the tower] has the look of an alien. And his home looks something like a sci-fi space hulk.”62

A scary episode took place later in 1991. On September 13 a 55-ton chunk of concrete fell from the side of Olympic Stadium after the ground under the structure apparently shifted. It crashed into a walkway above some underground offices used by the government of Quebec. No one was hurt (only about 50 of 450 workers had reported). However, the Expos were forced to play their last 13 home games on the road.

What was more, on September 25, club president Claude Brochu said that because of scheduling requirements, the 1992 season in Montreal was at risk if the National League did not receive a guarantee of safety within a few weeks.63 It emerged that inspections in 1985 and 1990 had shown growing cracks in Olympic Stadium’s supporting concrete ribs.64 A first-stage announcement came in early November, as the Quebec minister responsible for the OIB said that engineers had found the stadium structurally sound. 65 It took a few weeks longer for clearance on the Kevlar roof, though, which had suffered several rips in a severe June windstorm.66

Others read deeper significance into the event, beyond concerns about structural integrity and public safety. The New York Times wrote, “Because the stadium is a landmark, the crumbling of its wall was taken by many here as a symbol of the economic and social problems that have gnawed away at the city’s self-confidence.”67 The article quoted Mayor Jean Doré, who had ended Jean Drapeau’s reign in 1986. “In the period from 1960 to 1985, those ‘great events’ put us on the map. But we paid a price, and that was that we did not adopt a strategy for basic economic renewal until the mid-1980s.” Others have argued, however, that by attracting and staging the Olympics, Montreal helped the entire national image of Canada.

Numerous big-name rock and pop acts came to Olympic Stadium over the years. To cover all these concerts is beyond the scope of this article, but some of the most prominent stars include (besides U2 and Pink Floyd) the Rolling Stones, David Bowie, the Jacksons, and AC/DC. The most infamous episode came on August 8, 1992, during a tour headlined by hard-rock bands Metallica and Guns n’ Roses. Both acts cut their performances short. Metallica’s lead singer, James Hetfield, suffered severe burns in a pyrotechnics explosion. Axl Rose, the prima donna frontman of G n’ R, called his band off the stage early, complaining of throat problems. A riot erupted; Montreal police sealed off the area and shut down four nearby subway stations.68

According to Stephen Bronfman (son of Charles), “The Big O was always awful for concerts – horrible acoustics. In fact, the shows on U2’s last tour [Zooropa, 2011] were held at the old Hippodrome, where the band and promoters spent C$3-4 million erecting temporary stands, etc. for two nights – 80,000 people each night. They wouldn’t go to The Big O because of the acoustics.”69

This is the likely reason why opera came just once to Olympic Stadium, for a mammoth production of Verdi’s Aïda on June 16 and 18, 1988. Noted sound designer Roger Gans flew in four sections of huge Meyer MSL-10 stadium cabinets.70 To Gans, the challenge was always to fit the sound into the acoustics of the space.71

The Expos began to think about a new home as the 1990s wore on. In June 1997 Claude Brochu displayed plans for a new downtown stadium with a retractable roof. Labatt Breweries of Canada announced in May 1998 that it would invest in the ballpark. It looked as though Olympic Stadium was a lame duck, at least as far as the Expos were concerned.

Yet at best, Labatt Park would have been open for the 2001 season, so The Big O was still home. (The lobbying for a new park didn’t help its image.) In 1998 its Kevlar roof was replaced by a membrane made of Teflon-coated fiberglass panels. Montreal winters proved hard on the new roof, though – in January 1999 snow, slush, and meltwater caused one of the panels to give way while 200 workers were setting up an auto show inside. Fortunately just five people were injured.72

The hopes for Labatt Park effectively ended in the summer of 2000, when Expos managing general partner Jeffrey Loria (who had bought 24 percent of the team in December 1999) put plans for the new stadium on hold. Stephen Bronfman, who had taken a minority stake in the franchise alongside Loria, declined to buy out the New York art dealer.73

The final years of the club in Montreal are not a story that needs to be retold here, though it is worth noting the flurry of attendance in late August 2003, when manager Frank Robinson had his squad in the hunt for a wild card.74 The decision to hold Expos games in Estadio Hiram Bithorn is also a separate tale. Suffice it to say that the last homestand for Major League Baseball in Olympic Stadium ran from September 21-29, 2004. Montreal won just two of nine games, dropping the last five. The Florida Marlins – owned by Jeffrey Loria – swept the concluding series. Terrmel Sledge popped to third for the final out.

After the Expos left, Olympic Stadium proved still capable of drawing big crowds, notably in soccer. It hosted international matches in 2009 and 2010. In 2012 a team called the Montreal Impact joined Major League Soccer (MLS). The Impact had been playing since 1993 in various other leagues, but moved up. On March 17, 2012, the club made its debut before 58,912 at The Big O. (Its primary field, adjacent Saputo Stadium, was being expanded.) That May 12, the Impact broke that record – and set a new high for pro soccer in Canada – by drawing 60,860.

Nonetheless, Drapeau’s Folly remains vacant for much of the year – especially in winter, because of ongoing deterioration in the membrane roof. “It’s in such a poor state that the Impact had to move a spring game because of three-quarters of an inch of snow!” said Stephen Bronfman, whose memories of Olympic Stadium – “fond and not so fond” – dated from his early teens. “Bloody shame, the whole thing.”75 The neighboring nature museum, the Montreal Biodome (formerly the Vélodrome) is a much bigger draw. The future of the Big O, as of summer 2013, was still up in the air – although Olympic Park president David Heurtel was doing his best to change perceptions amid a three-year renovation program.76

“Unlike some of the stadiums in America,” said Roger Taillibert in 1986, “it [patrimoine, or cultural legacy] is not something you knock down in 10 years. It is an object that remains.”77 There are those who agree with him. In December 2012, after more than a year of study, a committee headed by Lise Bissonnette issued a report saying that “the stadium and the surrounding installations need to be recognized not as a money-draining blight, but as an important piece of Quebec’s cultural heritage.” One of the proposed changes that would make Olympic Stadium “a true park” is a return to a retractable roof. The National Post article that discussed the report also said, however, “The committee was not asked to put a price tag on its proposals, but Ms. Bissonnette said she is optimistic that over a 15-year period the transformation can be made.”78

Diametrically opposed is Post columnist Barbara Kay (mother of the Post’s Jonathan), who is respected for her brutally frank opinions. In response to the Bissonnette committee’s report, she wrote “‘Magnificent work’? ‘Cultural heritage’? Excuse me? In what sense does this monstrosity have anything to do with Quebec culture? Nothing, and let me count the ways.” She called Olympic Stadium a “huge, round, pale, sterile, soulless architectural excrescence” and concluded that “The only new money that should be spent on it is whatever it costs to tear it down.”79

OIB studies in 2005 pegged that cost at more than C$500 million, because the 12,000 prefabricated concrete pieces that make up the stadium would have to be dismantled. A new roof alone could cost $300 million.80 It’s a Scylla-and Charybdis course.

It’s a great leap of faith that Major League Baseball would ever place another franchise in Montreal, but rearguard forces made it their goal. Stepping up to lead those partisans was Warren Cromartie, a veteran of the 1981 Expos and head of the Montreal Baseball Project. A new downtown location clearly remained the favored option, yet The Big O was still viewed as a viable interim location – it became part of a feasibility study that started in March 2013.81 Thus, even at that date it was still conceivable that big leaguers just might take the field at Olympic Stadium again someday.

That came to pass in March 2014, when the Toronto Blue Jays played two spring training games against the Mets. The Jays have returned for preseason games in each subsequent year through 2019. The stadium remains in use for other events. including soccer. Meanwhile, the roof is still an issue. In 2017 the government of Quebec approved a replacement budgeted at C$250 million. As of February 2019, the timetable for completion was extended a year, from 2023 to 2024.

Roger Taillibert died in October 2019 at the age of 93. Former Montreal mayor Denis Coderre remembered the architect as “a man of vision” and “a genius” while describing Olympic Stadium as “one of the city’s greatest architectural pieces…part of the Montreal signature.” Yet Taillibert’s death renewed the debate over this structure – icon or white elephant? – that has now been running for more than four decades.

Last updated: October 4, 2019.

Select Other Quotes about Olympic Stadium

“For which of you, intending to build a tower, sitteth not down first, and counteth the cost, whether he have sufficient to finish it?”

— Judge Albert Malouf, head of the Malouf Commission, lecturing Jean Drapeau by quoting the Gospel (Luke 14:28)82

“If Montreal has any building that merits the title of monument it certainly is the Olympic Stadium. It has … beauty, clarity of style and function, harmony of the ensemble, which itself is well balanced and rhythmic. Its design is dynamic and vibrant, enclosing spaces by ample movement. The majesty of this structure, particularly from the infield, is impressive.”

— Jean-Claude Marsan, Quebec-born architect83

“The world’s largest toilet bowl.”

— Richie Hebner (then with the Philadelphia Phillies)84

Sources

Thanks to the following for their input: Alain Usereau, Patrick Carpentier, Stephen Bronfman.

Photo Credits

Courtesy of www.ballparksofbaseball.com

Internet Resources

baseball-reference.com

retrosheet.org

Official Report: Games of the XXI Olympiad, Montreal 1976 (library.la84.org/6oic/OfficialReports/1976/1976v2.pdf)

cfldb.ca

Olympic Stadium page on Clem’s Baseball (andrewclem.com/Baseball/OlympicStadium.html)

Merron, Jeff, “Olympic Stadium disaster timeline,” ESPN.com, April 22, 2003 (assets.espn.go.com/mlb/s/2003/0422/1542317.html)

agencetaillibert.com

“Montreal Olympics: Roger Taillibert speaks,” CBC Digital Archives (cbc.ca/archives/categories/sports/olympics/the-montreal-olympics-the-summer-games-of-76/taillibert-speaks.html). Originally broadcast December 16, 1975.

great-towers.com/towers/montreal-tower/

stadeolympiquemontreal.ca/ (French-language website of Claude Phaneuf that proclaims to tell “the real truth”)

Books

Auf der Maur, Nick, The Billion-Dollar Game: Jean Drapeau and the 1976 Olympics (Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, 1976).

Closing ceremony: Games of the XXI Olympiad, Montréal 1976, Montréal:

Comité organisateur des Jeux de la XXIe Olympiade, 1976.

Howell, Paul Charles, The Montreal Olympics (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2009).

Taillibert, Roger, «Notre cher Stade Olympique»: Lettres posthumes à mon ami Drapeau (Montreal: Editions Stanké, 2000).

Notes

1 “Quebec’s Big Owe stadium debt is over,” CBC News, December 19, 2006.

2 Graeme Hamilton, “What does the future hold for Montreal’s fallen Olympic Stadium?,” National Post, September 24, 2011.

3 The stadium is only one venue in a complex of several built on the site for the Olympics. Montrealers do call it “Le Stade Olympique” or “le Stade.”

4 Ronald King, “Le p’tit gars de la rue Adam.” La Presse (Montreal), July 13, 2004, S15.

5 Telephone interview, Charles Bronfman with Rory Costello, August 16, 2011.

6 Patrick Reddington, “Hall of Fame Catcher Gary Carter on the Washington Nationals, Montreal Expos and Tim Raines,” federalbaseball.com, August 11, 2010.

7 The exclamation point is part of his name as well as his uniform.

8 “Jean Drapeau,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, online edition (http://thecanadianencyclopedia.com/articles/jean-drapeau).

9 Richard Purser, “Just blame super-mayor,” The Sun (Vancouver, British Columbia), May 20, 1970, 4.

10 “Jean Drapeau”

11 “Montreal’s Olympic stadium,” Montreal Gazette, March 23, 1972, 8.

12 Éric Clément, “Roger Taillibert publie ses mémoires,” La Presse (Montreal), August 17, 2010.

13 Viau station also serves the Olympic Park. It is farther away from the stadium and many people chose/still choose to get off there because it is less crowded during events. It’s 5-10 minutes walking distance from the stadium proper.

14 Henry Milner, “City Politics,” in Dimitrios L. Roussopoulos, editor, The City and Radical Social Change (Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1982), 141.

15 Bob Dunn, “Expos Shiver at Roofless Park Prospect,” The Sporting News, December 20, 1975, 45.

16 Maury Brown, “The Team That Nearly Wasn’t: The Montreal Expos,” Hardball Times, January 16, 2006. This article draws quotes from a personal interview between McHale and SABR member Alain Usereau.

17 Ted Blackman, “Mayor of Montreal Homers in Ninth – Franchise Is Saved,” The Sporting News, August 24, 1968, 25.

18 Ted Blackman, “Wise Expos Will Avoid Clash with Hockey,” The Sporting News, November 16, 1968.

19 Ted Blackman, “A Covered Stadium? Montreal Will Have One,” The Sporting News, May 31, 1969, 11.

20 Ted Blackman, “New Stadium for Expos Up to Montreal Mayor,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1970

21 “70,000-Seat Stadium May Be Home of Expos in 1975,” The Sporting News, April 24, 1971, 21.

22 Ian MacDonald, “Expos’ Mastery of Pickoff Play Confounding Foes,” The Sporting News, May 13, 1972, 12.

23 Lester Smith, “Expos Boast Big Plus: Their Spirited Crowds,” The Sporting News, June 3, 1972, 21.

24 “Olympic Stadium Costs Continue to Soar,” Associated Press, March 28, 1976.

25 “Testimony Blames Firm for Olympic Overruns,” Associated Press, September 14, 1978.

26 Hubert Bauch, “Never look a gift house in the mouth,” Montreal Gazette, January 20, 1979, 51. “Probe boss angry at Montreal’s tactic,” Montreal Gazette, March 30, 1979, 3.

27 Olympic inquiry told why public bids were waived,” Canadian Press, September 13, 1978.

28 “Olympic Stadium Costs Continue to Soar.”

29 Michael Farber, “You get lunch, no apology from Big O architect,” Montreal Gazette, July 14, 1986, A-1, A-5.

30 Farber, “You get lunch, no apology from Big O architect.”

31 “Mayor pulls cord on Parachute Park,” Canadian Press, April 7, 1972.

32 Hubert Bauch, “A 10-year hangover followed a great, two-week party,” Montreal Gazette, July 12, 1986, A-4

33 “Lack of plans said cause of Olympic cost overruns.”

34 “City gets property tax order,” Montreal Gazette, December 18, 1976, 1. William Tetley, “The mayor isn’t beaten yet,” Montreal Gazette, January 5, 1977, 7.

35 Andrew Egan, “World’s Most Expensive Stadiums,” Forbes, August 6, 2008.

36 André Gagnon, “Three charged in Olympic Games fraud,” Montreal Gazette, September 19, 1980, 1.

37 “Prosecutor looks at Malouf report,” Montreal Gazette, June 5, 1980, 4.

38 “Lack of plans said cause of Olympic cost overruns,” Canadian Press, April 6, 1979.

39 “Olympic Stadium Montreal Problem,” Associated Press, August 4, 1976.

40 It also held the opening and closing ceremonies, the semifinals and finals in football, and the Grand Prix team jumping equestrian events.

41 The same was true of Toronto’s Exhibition Stadium, which hosted the Argonauts of the CFL. However, “the Ex” was constructed primarily for football and was retrofitted to serve the Blue Jays.

42 Ian MacDonald, “Charron won’t pamper Expos, ‘fat cats,’” Montreal Gazette, December 11, 1976. Ian MacDonald, “Bronfman Blast Delays Expo Stadium Contract,” The Sporting News, January 15, 1977, 41.

43 “All-Star Game Lost to Expos.” Associated Press, December 9, 1976.

44 Ian MacDonald, “Olympic Stadium talks ‘very sour,’ Expos may be back at Jarry Park.” Montreal Gazette, January 18, 1977: 16.

45 “Expos To Play Home Games At Montreal Olympic Stadium?” Palm Beach Post, February 11, 1977; “Expos Sign Park Deal.” Associated Press, March 4, 1977.

46 Régie des Installations Olympiques. The first word prompted Anglophones to nickname the board “the Reggie.”

47 Ted Blackman, “Chilly stadium brings a yearning for Jarry,” Montreal Gazette, April 16, 1977.

48 Christian Trudeau, “Out of Here: Home Runs in Canada,” SABR.org (http://sabr.org/research/out-here-home-runs-canada).

49 Frank Garland, Willie Stargell: A Life in Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2013), 162-163.

50 Joseph Durso, “Air Ball Comes to Olympic Stadium in Montreal,” New York Times, April 6, 1988.

51 “Stearns a Slam, Kingman a Slight,” Associated Press, June 2, 1977.

52 Durso, “Air Ball Comes to Olympic Stadium in Montreal.”

53 Bob Carruthers, Pink Floyd: Uncensored on the Record (Henley-in-Arden, England: Coda Books, 2011). Various other accounts support this story.

54 “Why they don’t like theBig O,” Montreal Gazette, August 5, 1978, 67.

55 On the undercard, the fight for the Canadian lightweight title had a tragic end. Gaetan Hart knocked out Cleveland Denny, and Denny absorbed so much punishment that he fell into a coma and died 17 days later.

56 “Expos off to Vancouver?” Associated Press, March 24, 1983.

57 “Expos’ lease includes new turf,” Montreal Gazette, August 1, 1983.

58 “Stadium Tower Work Is Halted in Montreal,” Associated Press, June 7, 1980.

59 Daniel Drolet, “At last: Big O to get a retractable roof,” Montreal Gazette, January 24, 1985, A1, A2.

60 Philippe Gohier, “The Big Owe,” Maclean’s, May 6, 2008.

61 Andy Riga, “Montreal ponders: Whither the Big O?” Winnipeg Free Press, August 21, 2010.

62 Jonathan Kay, “The majestic, awe-inspiring, faintly totalitarian absurdity of Montreal’s Olympic Stadium,” National Post, December 17, 2012. Something else that highlights the scale issue is the modest-sized statue of Jackie Robinson and two small boys that stands outside Olympic Stadium. It was originally, in 1986, put on the former site of Delorimier Stadium, where Robinson played in 1946, but was moved in 1987.

63 “Play Ball in Montreal? Not ’til Stadium’s Fixed,” Associated Press, September 26, 1991.

64 “Cracked ribs worsen at Olympic Stadium,” wire service reports, October 22, 1001.

65 “Expos to return to Olympic Stadium,” Baltimore Sun, November 8, 1991.

66 “Olympic Stadium declared safe again,” wire service reports, November 29, 1991.

67 John F. Burns, “The Proud City of ‘Great Events’ Has a Great Fall,” New York Times, February 14, 1992.

68 “Riot Erupts at Concert Starring Guns n’ Roses,” New York Times, August 11, 1992. “The Montreal police said rioters among the 53,000 audience members smashed stadium windows with an uprooted street lamp, looted a souvenir boutique, burned a sports car and Guns ‘n’ Roses T-shirts, and set dozens of small fires. About 300 club-wielding police officers chased rioters through the streets and fired tear gas to regain control.”

69 E-mail from Stephen Bronfman to Rory Costello, July 31, 2013. The website u2gigs.com confirms that U2 played at Olympic Stadium during the Joshua Tree tour (1987) and the ZOO TV tour (1992), but did not come back after the PopMart tour (1997). The PopMart tour prompted Stephen Bronfman to become an investor in the company that promoted the concerts.

70 Hypermedia, Mix Publications, 1988.

71 Theatre Crafts, Volume 24, 1990.

72 “Olympic Stadium’s Roof Collapses,” New York Times, January 19, 1999. “Olympic Stadium Reopening Date Uncertain after Roof Collapse,” Miami Herald, January 20, 1999.

73 “Stephen Bronfman to make crucial decision in bid to keep Expos alive,” Canadian Press, June 17, 2000.

74 Charlie Nobles, “For the Expos, It’s All a Wild Card,” New York Times, September 1, 2003.

75 E-mail from Stephen Bronfman to Rory Costello, July 31, 2013.

76 Brendan Kelly, “Game changer enlivens Big O,” Montreal Gazette, July 9, 2013.

77 Farber, “You get lunch, no apology from Big O architect.”

78 Graeme Hamilton, “Facing the test of time: Retractable roof could give ‘dreadful’ Olympic Stadium a lively future in Montreal, committee says,” National Post, December 13, 2012.

79 Barbara Kay, “The Olympic stadium is a disaster, not ‘Quebec culture,’” National Post, December 12, 2012.

80 Hamilton, “What does the future hold for Montreal’s fallen Olympic Stadium?”

81 “Former Expo Cromartie and group to launch baseball feasibility study,” CTV News, March 20, 2013 (http://montreal.ctvnews.ca/former-expo-cromartie-and-group-to-launch-baseball-feasibility-study-1.1203923). Jack Todd, “A baseball dream is reborn,” Montreal Gazette, March 25, 2013. Read more: http://montreal.ctvnews.ca/former-expo-cromartie-and-group-to-launch-baseball-feasibility-study-1.1203923#ixzz2ZhpsIRJJ

82 Bauch, “A 10-year hangover followed a great, two-week party.”

83 Jean-Claude Marsan, Montreal in Evolution (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1981), 392.

84 The date Hebner made this remark is uncertain, though it might even have been the very first game in 1977. The earliest available reference to it is in Ken Tingley, “Olympic Stadium: a definite cement motif,” Plattsburgh (New York) Press-Republican, May 8, 1980.