Wiedenmayer’s Park (Newark, NJ)

This article was written by Bill Lamb

On July 17, 1904, future Hall of Famer Clark Griffith pitched the homestanding New York Highlanders to a 3-1 victory over the Detroit Tigers in a contest that was atypical for the era in several respects. First, the game, a makeup of an earlier rainout between the clubs, was played on a Sunday. Avoidance of New York City blue laws that prohibited playing professional baseball on the Sabbath was achieved by another unusual aspect of the proceedings: a change of venue. The contest was moved from Manhattan’s Hilltop Park and staged some 15 miles to the southwest in nonrestrictive Newark, New Jersey. Finally, the Tigers-Highlanders match has the distinction of being the first, last, and only regular season major-league game ever played at Wiedenmayer’s Park, otherwise the home ballpark of Newark’s clubs in the Eastern and International Leagues of 1902-1918. Largely abandoned after World War I and destroyed by fire a few years thereafter, Wiedenmayer’s Park was New Jersey’s first noteworthy ballpark. The story of this long-vanished hub of minor-league baseball follows.

The Wiedenmayer Brewery: Beer Begets a Baseball Park

Given its substantial number of inhabitants of German descent, mid-nineteenth-century Newark was home to a multitude of breweries.1 Among the most prominent was that established around 1840 by Christian Wiedenmayer, later mayor of Newark. The important family actor in our narrative is his son, George W. Wiedenmayer (1848-1909). When George came of age, he entered the family business, but set up his satellite brewery operation in New Brunswick, not Newark. Capable and ambitious, he greatly expanded the brewing capacity at the company’s central facility when he returned to Newark to assume control of the family business in 1876. And like his father before him, George, a Democrat, soon became a force in local politics, serving several terms as president of the Newark Common Council. In 1889 he was also elected to the New Jersey State Assembly.

By then, the city had long established itself as a hotbed of baseball, with amateur nines calling Newark home as early as 1855. When professional minor-league baseball began to take root in the early 1880s, clubs soon took up residence there. Beginning with the 1884 Newark Domestics of the newly formed Eastern League, Newark hosted local teams in a variety of minor-league circuits (International League, Central League, Atlantic Association, Atlantic League) through the end of the century.

For various reasons that are outside the scope of this story, Newark was obliged to do without a professional baseball club during the 1901 season. However, plans were soon afoot to rectify that situation. Over the winter, a group of prominent local businessmen, including George Wiedenmayer and several other city brewery owners, formed the Newark Base Ball and Amusement Company. Their objective was placement of a Newark franchise in the recently reconstituted Class A minor Eastern League. To that end, veteran minor-league manager Walter Burnham was placed under contract, tasked with signing playing talent, game management and strategy, and general oversight of the prospective ballclub’s operations. But an immediate obstacle confronted the venture: the lack of a ballpark suitable for a high minor-league team in Newark. Promptly coming to the rescue was George Wiedenmayer.2

Since at least the late 1890s, Newark amateur baseball, football, and soccer clubs had been afforded access to a green expanse located on Hamburg Place.3 The property was owned by George Wiedenmayer and sat adjacent to the grounds of his Newark brewery operation. This local sporting venue was dubbed “Wiedenmayer’s Park,” and quickly became the focus of attention of the city’s ballclub backers. As a viable ballpark location, the site was not without problems. The grounds were not situated in or near the city’s downtown business and commercial core, but in a gritty industrialized neighborhood known as the Ironbound, some distance to the northeast. And while relatively open and flat, the playing field was rutted, marshy in spots, and imbued with the stench emanating from the garbage-strewn Passaic River close by. Strongly in the location’s favor, however, was the fact that the same trolley and rail service that brought workers to the Ironbound each day would also deposit Newark baseball fans within short walking distance of the site. More important, the property was owned by franchise supporter George Wiedenmayer, and he was willing to make it available. The arrangement subsequently reached replicated, if unintentionally, that involving the Polo Grounds and the club owners of the New York Giants: the new ballpark would be built and owned by the Newark Base Ball and Amusement Company, but the land on which it sat would be leased from Wiedenmayer & Sons, Inc., George’s brewing company.4

The Early Years

Once the real estate details had been worked out, ground was broken and construction commenced at the breakneck pace common to the wooden ballpark era. By early April 1902, Wiedenmayer’s Park was ready for exhibition-game play.5 Describing the ballpark in its earliest years is problematic, as the edifice was a work in constant progress throughout the first decade of its existence. [Note: A description of Wiedenmayer’s Park in its final configuration is offered within.] Suffice it for now to say that the initial iterations of the ballpark had few admirers. The original Wiedenmayer’s Park was small and poorly landscaped, and offered few amenities for either players or spectators. At season’s end, the Spalding Guide observed that the “Newark club would find it advantageous to improve the grounds,” comparing them unfavorably to West Side Avenue Park, the ballpark used by the Jersey City Skeeters, a nearby Eastern League rival.6 Commentary by a Sporting Life correspondent was blunter; it called Wiedenamyer’s Park an “eyesore.”7

The newly christened Newark Sailors began the Eastern League campaign on the road, going 4-3 in their first seven contests and setting the stage for the official debut of Wiedenamayer’s Park as a minor-league ballpark. On May 8, 1902, the home opener was preceded by a parade, speeches by local dignitaries, and a ceremonial first pitch thrown by Newark Mayor James M. Seymour.8 The “large and enthusiastic crowd of baseball lovers”9 actually totaled only 1,800.10 That suggests the intimate size of the initial version of Wiedenmayer’s Park. The Toronto Maple Leafs then spoiled the festivities with a 9-4 beating of the home side. The outcome was a harbinger of things to come. Toronto would go 85-42 (.669) and capture the EL pennant. Newark headed in the opposite direction, its woeful final log of 39-98 (.285) securing the league cellar, 51 games behind the Maple Leafs.

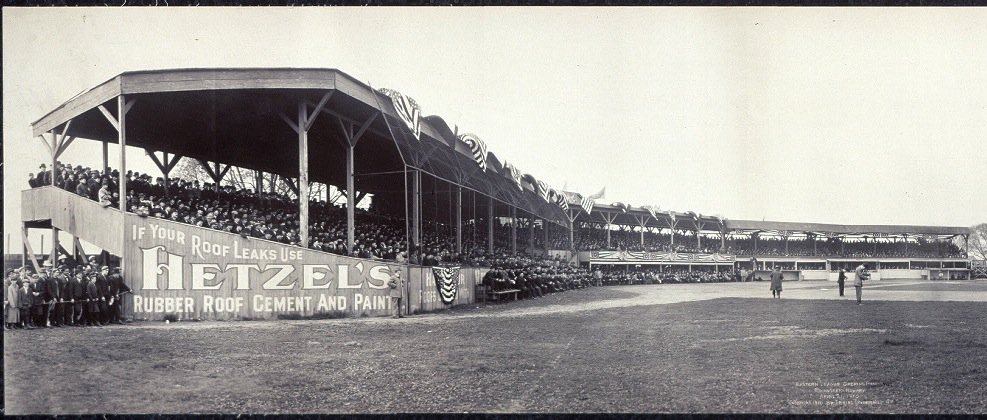

In nine seasons as an Eastern League member, Newark never won a championship (although the club finished second in 1909 and 1910). Notwithstanding that, the operation consistently turned a profit for the Newark Base Ball and Amusement Company. Much of that revenue was poured into improvement and expansion of Wiedenmayer’s Park. Prior to the start of the 1903 campaign, club major domo Burnham had the uneven, often soggy infield dug up and large quantities of sand laid down to improve drainage. The infield was then resodded and rolled to play dry, fast, and smooth.11 During the ensuing offseason, the first of several major ballpark renovations was completed. A new 1,400-seat grandstand with roofing was installed behind the home plate area. “Private boxes with opera chairs have been placed at the front and arrangements made for the convenience of women patrons,” reported Sporting Life.12 The infield was again resodded, while the outfield dimensions were deepened by 30 feet.13 The covered grandstand was extended along first base and third base, while bleacher sections were constructed along the right- and left-field foul lines. A clubhouse behind the grandstand was also added to the grounds.14 By the time the Tigers-Highlanders game of July 1904 was played, Wiedenmayer’s Park was fully equipped to accommodate the 6,700 fans who attended the contest.

Just before the 1907 season started, rumor had it that the Heller & Mertz Chemical Company, an expansion-minded dye and alkaline manufacturer whose plant bordered the ballpark, was attempting to acquire the Wiedenmayer’s Park property.15 But nothing came of such reports – for the time being. The following year, the Newark ballclub acquired a new nickname (Indians) and a new field leader, George Stallings.16 After several offseason conferences with George Wiedenmayer, Stallings announced plans for additional improvements to the Newark grounds. In the weeks thereafter, the grandstand behind home plate was enlarged to seat another 1,000 spectators, while bleacher sections were placed behind the right-field fence. This brought the seating capacity of Wiedenmayer’s Park to 8,000.17 The ballpark’s early years, however, ended on a somber note. On September 5, 1909, George Wiedenmayer died “after a long illness from a complication of diseases” at his summer home in Toms River, New Jersey.18 He was 61. George’s role with the Newark ballclub was assumed by his sons Gustav and Joseph, but they would never wield the degree of influence over franchise affairs asserted by their father.

Heyday and Decline

Under new field manager Joe McGinnity, the Newark Indians finished a strong second in the 1909 Eastern League pennant chase. And on Opening Day 1910, more than 10,000 fans were on hand at Wiedenmayer’s Park to witness McGinnity pitch the home team to a 2-1 victory over the Rochester Bronchos. Unhappily for the Newarkers, Rochester prevailed in the long run, edging out the Indians for the 1910 EL championship. But with club fortunes on the upswing, the Newark Base Ball and Amusement Company poured more money into its ball grounds. As the 1911 season loomed, sportswriter Edward S. Gearheart proclaimed that “great changes have been made and fans will hardly recognize the fine, newly-sodded field as old Wiedenmayer’s Park.”19 At a cost of $3,000, vast quantities of ashes were laid down beneath new field turf to fill in ruts and marshy spots. The ballpark was expanded as well, with the outfields considerably enlarged. “Hard hit grounders getting past the outfielders will [now] likely be home runs,” predicted Gearheart.20 The ballpark seating capacity was increased to 13,000, with 2,000 more temporary seats on hand for use “in a pinch.” With standing room available in open areas behind the left- and left-center-field fences (and in front of them in the just-deepened outfield, when necessary), Gearheart estimated that the new and improved Wiedenmayer’s Park was capable of accommodating up to 20,000 spectators.21

Nor were amenities neglected. A large new ladies’ restroom was decked out with mission furniture, upholstered reclining chairs, a telephone booth, and daily fresh flowers, with a matron stationed in the facility to ensure provision “of all things necessary for the comfort of the fair sex.”22 The wooden ballpark received a fresh coat of paint – steel gray with metallic brown trim – while new steel seats were installed in the grandstand.23 The danger of fire, meanwhile, was “reduced to zero by the installation of a complete system of fire protection.”24 All in all, observed Gearheart, Wiedenmayer’s Park was now a ballpark that Newark fans could “be proud of.”25

Although the precise contours of the grounds went undiscovered by the writer, the Gearheart reportage and circa 1911 photographs support the view that when fully developed, Wiedenmayer’s Park was a first-rate Deadball Era minor-league ballpark. Working from a 1912 Robinson Atlas diagram of the grounds, Ballparks Research Committee co-chairman Ron Selter calculates spacious outfield dimensions: LF-373/LC-446/CF-472/RC-387/RF-340.26 In its final iteration, Wiedenmayer’s Park was a single-level ballpark, with a covered first-base-to-third base grandstand and open bleachers ringing the playing field, except for empty space behind the fences in left and left-center field. But regrettably, Wiedenmayer’s Park would remain in its prime for only a few seasons.

The ballpark’s decline coincided with a change in ownership of the Newark Indians. In late 1912 a majority interest in the franchise, now affiliated with the Double-A International League,27 was acquired by the newly formed Newark Amusement and Exhibition Company. A New York City manufacturer and club investor named George L. Solomon was installed as club president, with Joseph Wiedenmayer elected VP.28 But in reality, the franchise was controlled behind the scenes by a National League force: Brooklyn boss Charles H. Ebbets and his partners in the Dodgers.29 Lacking local knowledge and more concerned about advancing Brooklyn interests than those of the Newark club, the new regime did not place a priority on operation of the Indians and was viewed with hostility by many Newark baseball fans. A particular fan irritant was new club President Solomon, who intruded on the prerogatives of manager Harry Smith, publicly quarreled with the sportswriters of the Newark Evening News, and generally made a nuisance of himself. Despite that, the Newark Indians captured the 1913 International League pennant. This success, however, did not dispel the widespread rumor that Ebbets had put the Newark franchise up for sale.30 But soon thereafter, he decided that the Newark ballclub was a good landing spot for footloose son Charles H. Ebbets Jr., and had him installed as club president.31

Under the stewardship of Ebbets Jr., the Indians promptly tumbled to fifth place and incurred a substantial financial loss.32 More ominously, oil tycoon Harry Sinclair had decided to invade Newark with a 1914 Federal League championship club transplanted from Indianapolis. With the Indians having a secure lease on Wiedenmayer’s Park and no suitable ballpark building sites in Newark proper available to Sinclair, he was compelled to place his Newark Peppers across the Passaic River in the abutting mini-city of Harrison, New Jersey. By mid-April 1915, Harrison Park, a spacious, modern ballpark, was ready to host the Peppers. But after a capacity-plus crowd upward of 30,000 made the inconvenient trek to the Peppers’ home opener – there was no direct trolley or rail service from Newark to Harrison Park and walking across the Jackson Avenue Bridge was both difficult and hazardous – attendance fell off sharply. Yet next to no one was attending the games of the Newark Indians. On July 2, 1915, the Indians abandoned Newark, relocating to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. And before season’s end, the money-losing franchise was forfeited to the International League.33

The demise of the Federal League during the winter of 1915-1916 once again made Newark an attractive minor-league venue. Shortly thereafter, the Newark territory and franchise rights were acquired by baseball-savvy investors James H. Price and Fred Tenney. But the new club owners were not disposed to pay the high fee demanded for rental of Harrison Park.34 To Price and Tenney, it made more economic (and geographical35) sense to renovate Wiedenmayer’s Park instead.36 The wooden ballpark had suffered from the lack of maintenance that had accompanied its abandonment the previous summer. To remedy that, carpenters, painters, and other repairmen were dispatched to refurbish the ballpark.37 But the halcyon days of Wiedenmayer’s Park were now behind it. The 1916 Indians plummeted to the IL cellar. Soon thereafter, the approach of World War I began to have a chilling effect on sport, particularly minor-league baseball. Before the 1918 season, a new ownership group headed by late-nineteenth-century Boston Nationals star Tommy McCarthy took control of the club, now called the Newark Bears. Although the International League was one of the few minor-league circuits able to complete the 1918 season, the future looked uncertain. But shortly after the season ended, the issue was rendered moot – at least as it concerned Wiedenmayer’s Park.

In early December 1918, the neighboring Heller & Mertz Chemical Company managed to acquire title to enough of the real property of Wiedenmayer’s Park so as to render the grounds unusable for professional baseball.38 Reluctantly, the Newark Bears transferred their operation to Harrison Park. The time of Wiedenmaye’’s Park as home to Newark minor-league baseball was over. Yet just before it closed its gates, Newark’s first significant ballpark staged probably its most celebrated event – a championship boxing match. On September 23, 1918, more than 10,000 fight fans entered Wiedenmayer’s Park to see welterweight champion Ted “Kid” Lewis and lightweight titleholder Benny Leonard battle to an eight-round no-decision.39

Demise and Aftermath

Apparently, expansion of the Heller & Mertz plant did not consume the entirety of the old ballpark’s playing field. Nor were the grandstand and bleachers totally disassembled. During the summers of 1919 and 1920, therefore, the remnants of Wiedenmayer’s Park hosted games played by the amateur Ironbound Manufacturers League.40 Thereafter, the grounds lay idle.

In May 1925 what remained of Wiedenmayer’s Park was totally destroyed by fire. Yet within a year, the departed ballpark, like the phoenix, rose from the ashes. The property was purchased by minor-league entrepreneur Charles L. Davids, who erected a modern steel-reinforced baseball stadium atop the very footprint of Wiedenmayer’s Park. Originally called Davids Stadium but renamed for New York Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert in 1931, the site served as the home ballpark for the juggernaut Newark Bears farm teams of the late 1930s-early 1940s Yankees. Ruppert Stadium was razed in 1967, and today an industrial park sits on the property. Sadly, no memorial to long-vanished Wiedenmaye’s Park or its successors graces the site.

Acknowledgments

This article was originally published in the December 2019 issue of Palaces of the Fans, the newsletter of SABR’s Ballparks Research Committee. This version, which contains some amendments, was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Notes

1 By the 1890s, no fewer than 57 different breweries were located in Newark. Today only the Budweiser plant remains operational.

2 George Wiedenmayer exercised power but generally preferred to operate quietly behind the scenes. The visible actors on the board of directors of Newark’s early-1900s minor league clubs were his sons Gustav and Joseph.

3 See “Games of Baseball, Jersey Journal (Jersey City), April 20, 1899: 8; “Association Football,” Jersey City News, October 2, 1999: 4.

4 From 1889 on, various iterations of the Polo Grounds were constructed and owned by the club owners of the New York Giants. The far north Manhattan real property on which the ballpark sat was not. Rather, it had to be leased from the wealthy and vastly propertied Gardiner-Lynch family via its estate agents, first James J. Coogan, thereafter his heiress wife, the formidable Harriet Lynch Coogan.

5 The first game played at Wiedenmayer’s Park was an April 5, 1902, exhibition game between Newark’s new Eastern League club and the semipro Star Athletics. From that day to this, the ballpark’s name was often misspelled. The correct spelling is WiedenMAYER, not WiedenMEYER.

6 1903 Spalding Guide, 41.

7 See James F. Grealey, “Newark News,” Sporting Life, April 30, 1904: 17.

8 See “Toronto a Winner in Opening Game,” Newark Evening News, May 9, 1902: 6. Perhaps establishing a tradition of sorts for politicians, the mayor’s first pitch failed to reach home plate in the air.

9 “Toronto a Winner.”

10 The attendance figure is provided in “Thielman Wins for Toronto at Newark,” Worcester Daily Spy, May 9, 1902.

11 As per “Eastern League News,” Sporting Life, April 25, 1903.

12 Grealey.

13 Grealey.

14 As reported in “Eastern League Events,” Sporting Life, March 19, 1904: 6. These improvements to Wiedenmayer’s Park were implemented only after efforts to secure new ballpark grounds near Newark’s city center had come up empty.

15 See e.g., Sporting Life, April 17, 1907: 22. Vintage photos of Wiedenmayer’s Park often depicted the Heller & Mertz smokestacks that loomed behind the third-base stands.

16 Stallings would later become the acclaimed field leader of the 1914 Miracle Boston Braves.

17 As reported in “Improvements in Newark,” Sporting Life, April 11, 1908: 17.

18 Per “G.W. Wiedenmayer Dead,” New York Times, September 7, 1909: 9.

19 Edward S. Gearheart, “Newark News,” Sporting Life, April 22, 1911: 14.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid. Under ordinary conditions, the deep outfield doubled as an automobile parking area.

22 Ibid.

23 The steel seats were an innovation recently introduced at Shibe Park and Forbes Field.

24 Gearheart.

25 Gearheart.

26 Email of Ron Selter to the writer, January 3, 2020.

27 The changes in name and classification were cosmetic. The eight clubs in the 1912 International League were the same as the eight members of the 1911 Eastern League.

28 Per “In New Hands,” Sporting Life, December 28, 1912: 11.

29 Ebbets had purchased a minority share in the Newark club in 1911. Under the new regime, he and his Brooklyn club partner Ed McKeever held 70 shares of Newark stock, while Solomon held another 45. The Wiedenmayer brewing company was the only other significant stockholder with 36 shares, while a sprinkling of shares was retained by original Newark club backers Abram Feist (8), John McLaren (2), and C.P. Schmidt (2).

30 See e.g., “Newark Club Still on the Market,” Trenton (New Jersey) Evening Times, November 1, 1913.

31 As reported in “Ebbets, Jr. President of Newark Club,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 3, 1913: 12: “Ebbets, Jr. to Head Newark,” Colorado Springs (Colorado) Gazette, December 6, 1913: 6, and elsewhere. Erstwhile President Solomon, meanwhile, was demoted to club vice president.

32 Per John G. Zinn, Charles Ebbets: The Man Behind the Dodgers and Brooklyn’s Beloved Ballpark (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2019), 148.

33 Earlier, Ebbets and McKeever had sold their interest in the Newark franchise to Solomon for a nominal $1, but he and partner Henry Medicus were unable to meet franchise financial obligations. In the end, the International League assumed ownership of the Newark club, per “Newark Still League Territory,” Sporting Life, July 17, 1915: 19. The club’s debts included about $2,000 in unpaid real property rental fees owed to the Wiedenmayer brewing company, according to “Can Get Newark Grounds,” Richmond (Virginia) Times-Dispatch, January 26, 1916: 8.

34 As part of a tentative settlement with Federal League club owners, the National Commission, Organized Baseball’s governing body, agreed to lease Harrison Park from Sinclair for the next 20 years at $10,000 per annum. The Commission expected that a good part of this expense, however, would be recouped from a new minor-league team paying rent for use of the Sinclair-built ballpark.

35 It was no secret that many Newark baseball fans resented their city’s team playing elsewhere and had refused to attend games at Harrison Park.

36 See “Price and Tenney Prefer Baseball Park in Newark,” Newark Sunday Call, March 5, 1916: 11.

37 Per “Minor League News and Gossip,” Sporting Life, April 1, 1916: 12. The repairs included rebuilding the ballpark clubhouse, damaged by a recent fire.

38 See “Picked Up Outside of National League Meeting,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 12, 1918: 4.

39 As reported on newspaper sporting pages nationwide. At the time in many states, an official victory could only be awarded based on a knockout or disqualification. Sportswriters covering the bout between the two future boxing hall of famers were about evenly divided on whether Lewis or Leonard had gotten the better of the action. At the match’s end, both champions retained their respective titles.

40 As reported in various issues of Speed Up, the official weekly of the Submarine Boat Corporation of Newark.